ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Do all prostate cancer patients want, and experience shared decision making prior to curative treatment?

Mona Otrebski Nilssona,b, Kirsti Aasb,c, Tor Å. Myklebusta,d, Ylva Maria Gjelsvika, Erik Skaaheim Hauga,e,f, Sophie D. Fossåg* and Tom Børge Johannesena*

aCancer Registry of Norway, Oslo, Norway; bFaculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; cDepartment of Urology, Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog, Norway; dDepartment of Research, Møre and Romsdal Hospital Trust, Ålesund, Norway; eDepartment of Urology Vestfold Hospital Trust, Tønsberg, Norway; fInstitute of Cancer Genomics and Informatics Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway; gNational Advisory Unit on Late Effects after Cancer Treatment, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

ABSTRACT

Objective: In comparable men with non-metastatic prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy (RP), radiotherapy (RAD) and active surveillance (AS) are treatment options with similar survival rates, but different side-effects. Healthcare professionals consider pretreatment shared decision making (SDM) to be an essential part of medical care, though the patients’ view about SDM is less known. In this article, we explore prostate cancer (PCa) patients’ SDM wish (SDMwish), and experiences (SDMexp).

Material and methods: This is a registry-based survey performed by the Cancer Registry of Norway (2017–2019). One year after diagnosis, 5,063 curatively treated PCa patients responded to questions about their pre-treatment wish and experience regarding SDM. Multivariable analyses identified factors associated with SDM. Statistical significance level: p < 0.05.

Results: Overall, 78% of the patients wished to be involved in SDM and 83% of these had experienced SDM. SDMwish and SDMexp was significantly associated with decreasing age, increasing education, and living with a partner. Compared with the RP group, the probability of SDMwish and SDMexp was reduced by about 40% in the RAD and the AS groups.

Conclusion: Three of four curatively treated PCa wanted to participate in SDM, and this wish was met in four of five men. Younger PCa patients with higher education in a relationship, and opting for RP, wanted an active role in SDM, and experienced being involved. Effective SDM requires the responsible physicians’ attention to the individual patients’ characteristics and needs.

KEYWORDS: Prostate cancer; treatment; shared decision making; wish; experience

Citation: Scandinavian Journal of Urology 2023, VOL. 58, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.2340/sju.v58.14730.

Copyright: © 2023 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing on behalf of Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes, provided proper attribution to the original work.

Received: 15 June 2023; Accepted: 23 October 2023; Published: 20 December 2023

*CONTACT Mona Otrebski Nilsson moni@kreftregisteret.no The Section for Analysis and Research, Cancer Registry of Norway, Ullernchausseen 64, 0379 Oslo, Norway

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.2340/sju.v58.14730

*Shared last authorship.

Competing interests and funding: The authors report no conflict of interest.

This work was financially supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society (Grant no. 33528), the Movember Foundation (Grant no. 170116001) and the Prostate Cancer Society (Grant no. 2022/FO387087). Sophie Dorothea Fosså is funded by the Norwegian Radium hospitals’ legacies (Grant no. 1607 4502516).

Introduction

Men diagnosed with non-metastatic prostate cancer (PCa) may face a difficult decision when multiple treatment options are available [1]. The most common curative treatment options are radical prostatectomy (RP), high-dose radiotherapy (EQD2 ≥ 74 Gy) or active surveillance (AS) [2]. In patients with comparable stage and tumor grade, these treatments are followed by similar long-term survival rates in randomized trials, but have different side-effects within the urinary, bowel, sexual and/or hormonal domains [3,4]. In clinical practice, pre-treatment shared decision making (SDM) has become an important part of care in men with newly diagnosed PCa. SDM has been shown to increase the patients’ satisfaction with the final therapy, provide less unmet expectations and reduce post-treatment decisional regret [5,6].

However, there are few population-based studies focusing on cancer patients’ wishes and experiences related to SDM, respectively, SDMwish and SDMexp [7,8]. Two large studies [9,10] and few smaller studies, consisting of relatively small sample sizes and highly selected patient groups, have investigated SDMwish and/ or SDMexp in PCa patients [11–18]. Still, there is a need for expanded knowledge about SDMwish and SDMexp in the real-world setting, emphasizing the patients’ view on SDM. With this background, our survey-based study in 1-year PCa-survivors aimed to:

- Assess the proportion of patients with potentially curable PCa who report to have wished pre-treatment SDM.

- Describe the number of patients’ who experienced SDM.

- Explore factors associated with the wish to be involved in, and experiences of, SDM.

We hypothesized that PCa patients’ age, education and functional status were associated with SDMwish and SDMexp.

Patients and methods

Patients

The patients included in this study had been registered with a PCa diagnosis in the Norwegian Prostate Cancer Registry (2017–2019), a sub-registry of the Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN) [19]. The following information was extracted from the database; basic diagnosis- and treatment-related data such as tumor characteristics and patient age, and data on previous cancer (yes vs. no). Date of RP or start of RAD were registered. Patients allocated to the AS strategy were identified by the registration form submitted to the CRN at diagnosis, excluding men following watchful waiting strategy. Performance status was rated based on the ECOG scale (0: normal activity, 1: some symptoms, but still near fully ambulatory, 2: less than 50% and 3: more than 50% of daytime in bed, and 4: completely bedridden), further stratified as: 0; no functional problems, ≥1; functional problems [20]. The risk groups of the primary tumor were described according to the EAU guidelines (low-, intermediate- and high-risk) [2]. Age at diagnosis was categorized into <60, 60–69 and ≥70 years.

In 2017, the CRN initiated a questionnaire-based prospective study with the aim to explore the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and side-effects in new PCa patients before (baseline) and 1 and 3 years after primary treatment for PCa. In relation to our study, outcomes in the 1-year questionnaire contained two questions from the Cancer Patient Experiences Questionnaire (CPEQ) [21–23], which were slightly modified to assess PCa patients’ SDMwish and SDMexp at the time of diagnosis:

- “Did you want to be involved in the treatment decision regarding your prostate cancer?” and

- “Were you involved in the treatment decision regarding your prostate cancer?”

Responses were originally based on a 5-point scale but dichotomized for these analyses as: YES; “To a very large extent,” “To a large extent” or “To some extent,” versus NO; “To a small extent” or “Not at all” [23]. Responding patients also informed about their highest educational level; primary school; (≤9 years); secondary school/ high school (10–12 years); university degree (university/college) and their civil status; living with a partner versus being single.

Inclusion criteria for the present study were:

1) Diagnosed in 2017–2019 with PCa without metastasis. 2) RP or started pelvic RAD (EQD2 ≥ 74 Gy) within 12 months of diagnosis or start of AS. 3) Returning the 1-year follow-up questionnaires 12–18 months after the baseline survey invitation. 4) No second line local treatment before responding to the 1–year questionnaire.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics are presented by means and corresponding standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and absolute numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression models assessed the associations between SDMwish and SDMexp and selected covariates. Models were not only estimated on the total sample but also stratified by treatment groups. Predicted probabilities were calculated from the estimated models for specific covariate patterns, fixing the remaining covariates to their mean. Results are illustrated graphically. Statistical significance level was p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee of Health Region South-East in Norway (no. 2015/1294). Patients consented to participate in the study by returning the questionnaires.

Results

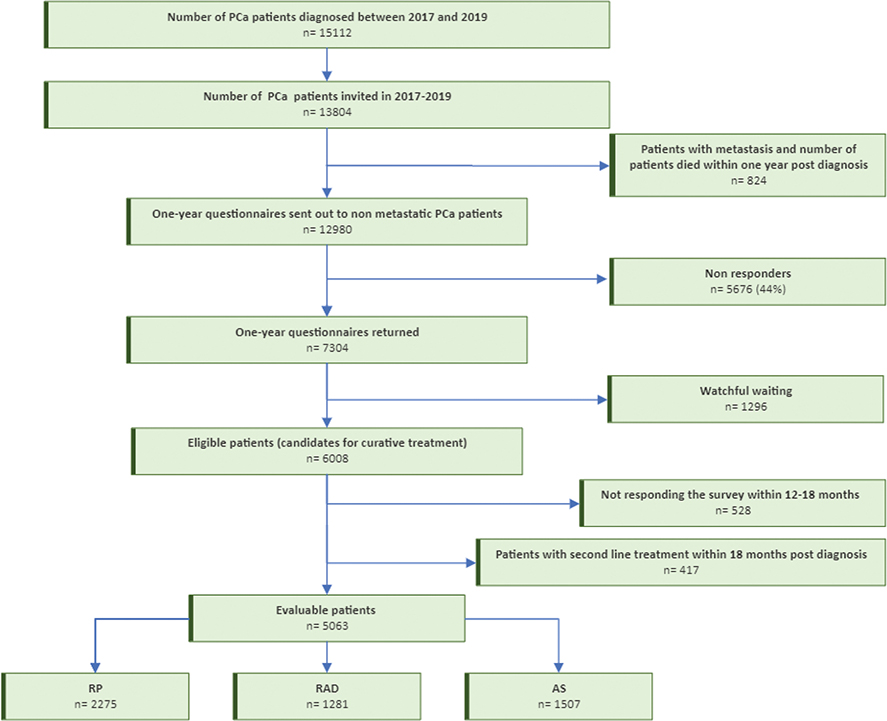

Overall, 7,304 (56%) 1-year responses were returned to CRN, resulting in 5,063 evaluable patients (Figure 1). The 1-year survey was submitted median 15 months (range 12–18 months) after the baseline survey invitation.

Figure 1. Patient flow chart. RP: radical prostatectomy; RAD: radiotherapy; AS: active surveillance.

Among evaluable patients, RP was performed in 45%, RAD in 25% and AS in 30% (Table 1). Patients in the RAD group were older, more often had had previous cancer, ECOG performance status ≥1 and reported less education compared with men in the RP or AS group (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

| RP | RAD | AS | Total | |

| n = 2,275 (45%) | n = 1,281 (25%) | n =1,507 (30%) | n = 5,063 (100%) | |

| Data from CRN | ||||

| Age at survey** | ||||

| All (mean, SD) | 65.2 (6.5) | 72.2 (5.4) | 66.8 (7.0) | 67.5 (7.0) |

| >70 | 623 (27%) | 935 (73%) | 547 (36%) | 2,105 (41%) |

| 60–69 | 1,218 (54%) | 315 (25%) | 728 (48%) | 2,261 (45%) |

| <60 | 434 (19%) | 31 (2%) | 232 (16%) | 697 (14%) |

| Previous cancer, n (%) | ||||

| No | 2,106 (93%) | 1,108 (86%) | 1,387 (92%) | 4,601 (91%) |

| Yes | 169 (7%) | 173 (14%) | 120 (8%) | 462 (9%) |

| ECOG, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 1,709 (92%) | 834 (77%) | 1,226 (88%) | 3,769 (87%) |

| ≥1 | 144 (8%) | 253 (23%) | 161 (12%) | 558 (13%) |

| Risk Group | ||||

| Low | 63 (3%) | 10 (1%) | 831 (60%) | 904 (20%) |

| Intermediate | 868 (43%) | 253 (22%) | 426 (30%) | 1,547 (34%) |

| High | 1,069 (54%) | 886 (77%) | 137 (10%) | 2,092 (46%) |

| Missing | 275 | 132 | 113 | 520 |

| Survey data, 1 year post baseline survey | ||||

| Level of education, n (%) | ||||

| Primary school | 301 (13%) | 275 (22%) | 186 (12%) | 762 (15%) |

| High school | 946 (42%) | 477 (38%) | 591 (40%) | 2,014 (40%) |

| University degree | 1,018 (45%) | 512 (40%) | 716 (48%) | 2,246 (45%) |

| Missing | 10 | 17 | 14 | 41 |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married/cohabitating | 1,906 (84%) | 1,040 (81%) | 1,257 (83%) | 4,203 (83%) |

| Single | 369 (16%) | 241 (19%) | 250 (17%) | 860 (17%) |

| RP, Radical prostatectomy; RAD, Radiotherapy; AS, Active surveillance; CRN, Cancer Registry of Norway; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; **no missing. | ||||

Overall, 78% of men wanted to be involved in SDM. This proportion was highest in the RP group (82%) and lowest in the RAD group (72%). In all three groups, SDMwish increased with decreasing age and increasing education. The relation between SDMwish and higher education was particularly evident in the RAD and in the AS group (Table 2). Among the PCa patients who wanted to be involved in SDM, 83% reported SDMexp (Table 3).

| RP | RAD | AS | Total | |||||

| n = 2,275 | n = 1,281 | n = 1,507 | n = 5,063 | |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| 399 (18%) | 1,876 (82%) | 360 (28%) | 921 (72%) | 378 (25%) | 1,129 (75%) | 1,137 (22%) | 3,926 (78%) | |

| Data from CRN | ||||||||

| Age at survey | ||||||||

| All (mean, SD) | 66.4 (6.1) | 65.0 (6.6) | 72.8 (5.0) | 72.0 (5.6) | 68.5 (6.7) | 66.2 (7.0) | 69.1 (6.5) | 67.0 (7.1) |

| >70 | 124 (20%) | 499 (80%) | 282 (30%) | 653 (70%) | 178 (33%) | 369 (67%) | 584 (28%) | 1,521 (72%) |

| 60–69 | 217 (18%) | 1,001 (82%) | 72 (23%) | 243 (77%) | 167 (23%) | 561 (77%) | 456 (20%) | 1,805 (80%) |

| <60 | 58 (13%) | 376 (87%) | 6 (19%) | 25 (81%) | 33 (14%) | 199 (86%) | 97 (14%) | 600 (86%) |

| Previous cancer, n (%) | ||||||||

| No | 354 (17%) | 1,752 (83%) | 314 (28%) | 794 (72%) | 338 (24%) | 1,049 (76%) | 1,006 (22%) | 3,595 (78%) |

| Yes | 45 (27%) | 124 (73%) | 46 (27%) | 127 (73%) | 40 (33%) | 80 (67%) | 131 (28%) | 331 (72%) |

| ECOG, n (%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 276 (16%) | 1,433 (84%) | 230 (28%) | 604 (72%) | 291 (24%) | 935 (76%) | 797 (21%) | 2,972 (79%) |

| ≥1 | 32 (22%) | 112 (78%) | 76 (30%) | 177 (70%) | 49 (30%) | 112 (70%) | 157 (28%) | 401 (72%) |

| Risk group | ||||||||

| Low | 5 (8%) | 676 (92%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) | 220 (26%) | 611 (74%) | 228 (25%) | 676 (75%) |

| Intermediate | 140 (16%) | 1,238 (84%) | 76 (30%) | 177 (70%) | 93 (22%) | 333 (78%) | 309 (20%) | 1,238 (80%) |

| High | 189 (18%) | 1,628 (82%) | 240 (27%) | 646 (73%) | 35 (26%) | 102 (74%) | 464 (22%) | 1,628 (78%) |

| Missing | 65 | 210 | 41 | 91 | 30 | 83 | 136 | 384 |

| Survey data, 1 year post baseline survey | ||||||||

| Level of education, n (%) | ||||||||

| Primary school | 77 (26%) | 224 (76%) | 108 (39%) | 167 (61%) | 78 (42%) | 108 (58%) | 263 (35%) | 499 (65%) |

| High school | 196 (21%) | 750 (79%) | 148 (31%) | 329 (69%) | 172 (29%) | 419 (71%) | 516 (26%) | 1,498 (74%) |

| University degree | 124 (12%) | 894 (88%) | 93 (18%) | 419 (82%) | 122 (17%) | 594 (83%) | 339 (15%) | 1,907 (85%) |

| Missing | 2 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 19 | 22 |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||||

| Married/ cohabitating | 319 (17%) | 1,587 (83%) | 279 (27%) | 761 (73%) | 296 (24%) | 961 (76%) | 894 (21%) | 3,309 (79%) |

| Single | 80 (22%) | 289 (78%) | 81 (34%) | 160 (66%) | 82 (33%) | 168 (67%) | 243 (28%) | 617 (72%) |

| Missing** | ||||||||

| RP, Radical prostatectomy; RAD, Radiotherapy; AS, Active surveillance; CRN, Cancer Registry of Norway; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; **no missing. | ||||||||

| RP n = 1,876 | RAD n = 921 | AS n = 1,129 | Total n = 3,926 | |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| 186 (10%) | 1,690 (90%) | 218 (24%) | 703 (76%) | 248 (22%) | 881 (78%) | 652 (17%) | 3,274 (83%) | |

| Data from CRN | ||||||||

| Age at survey | ||||||||

| All (mean, SD) | 64.5 (7.2) | 65.1 (6.5) | 72.2 (5.3) | 72.0 (5.7) | 67.2 (7.1) | 65.9 (6.9) | 68.1 (7.3) | 66.8 (7.0) |

| >70 | 48 (10%) | 451 (90%) | 153 (23%) | 500 (77%) | 95 (26%) | 274 (74%) | 296 (19%) | 1,225 (81%) |

| 60–69 | 90 (9%) | 911 (91%) | 63 (26%) | 180 (74%) | 120 (21%) | 441 (79%) | 273 (15%) | 1,532 (85%) |

| <60 | 48 (13%) | 328 (87%) | 2 (8%) | 23 (92%) | 33 (17%) | 166 (83%) | 83 (14%) | 517 (86%) |

| Previous cancer, n (%) | ||||||||

| No | 169 (10%) | 1,583 (90%) | 185 (23%) | 628 (77%) | 225 (21%) | 824 (79%) | 583 (16%) | 3,012 (84%) |

| Yes | 17 (14%) | 107 (86%) | 33 (31%) | 75 (69%) | 23 (29%) | 57 (71%) | 69 (21%) | 262 (79%) |

| ECOG, n (%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 143 (10%) | 1,290 (90%) | 145 (24%) | 459 (76%) | 196 (21%) | 739 (79%) | 484 (16%) | 2,488 (84%) |

| ≥1 | 14 (12%) | 98 (88%) | 49 (28%) | 128 (72%) | 34 (30%) | 78 (70%) | 97 (24%) | 304 (76%) |

| Risk group | ||||||||

| Low | 4 (7%) | 54 (93%) | 2 (29%) | 5 (71%) | 136 (22%) | 475 (78%) | 142 (21%) | 534 (79%) |

| Intermediate | 66 (9%) | 662 (91%) | 43 (24%) | 134 (76%) | 64 (19%) | 269 (81%) | 173 (14%) | 1,065 (86%) |

| High | 96 (11%) | 784 (89%) | 157 (24%) | 489 (76%) | 23 (23%) | 79 (77%) | 276 (17%) | 1,352 (83%) |

| Missing | 20 | 190 | 16 | 75 | 25 | 58 | 61 | 323 |

| Survey data, 1 year post baseline survey | ||||||||

| Level of education, n (%) | ||||||||

| Primary school | 24 (11%) | 200 (89%) | 43 (26%) | 124 (74%) | 24 (22%) | 84 (78%) | 91 (18%) | 408 (82%) |

| High school | 96 (13%) | 654 (87%) | 86 (26%) | 243 (74%) | 104 (25%) | 315 (75%) | 286 (19%) | 1,212 (81%) |

| University degree | 65 (7%) | 829 (93%) | 89 (21%) | 330 (79%) | 117 (20%) | 477 (80%) | 271 (14%) | 1,636 (86%) |

| Missing | 1 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 18 |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||||

| Married/cohabitating | 149 (9%) | 1,438 (91%) | 170 (23%) | 591 (77%) | 208 (22%) | 753 (78%) | 527 (16%) | 2,782 (84%) |

| Single | 37 (13%) | 252 (87%) | 48 (30%) | 112 (70%) | 40 (24%) | 128 (76%) | 125 (20%) | 492 (80%) |

| Missing** | ||||||||

| RP, Radical prostatectomy; RAD, Radiotherapy; AS, Active surveillance; CRN, Cancer Registry of Norway; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; **no missing. | ||||||||

Overall, a larger proportion of the prostatectomized men reported SDMexp compared with RAD and AS patients. Higher education increased SDMexp in all three groups. Increased SDMexp with decreasing age was particularly evident in the RAD and AS groups.

In the multivariable analyses including all patients, SDMwish and SDMexp were positively associated with decreasing age, increasing education, living with a partner, and being treated with RP (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

| a) SDMwish (n = 5,063) | p-value | b)SDMexp (n = 3,926) | p-value | |

| OR (CI) | OR (CI) | |||

| Age at survey | ||||

| ≥70 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 60–69 | 1.39 (1.17, 1.65) | <0.001** | 1.17 (1.00, 1.37) | 0.046** |

| <60 | 2.08 (1.58, 2.75) | <0.001** | 1.44 (1.14, 1.83) | 0.002** |

| Previous cancer | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.83 (0.64, 1.07) | 0.147 | 0.83 (0.66, 1.05) | 0.118 |

| ECOG | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥1 | 0.89 (0.71, 1.10) | 0.270 | 0.86 (0.70, 1.05) | 0.131 |

| Treatment | ||||

| RP | 1 | 1 | ||

| RAD | 0.69 (0.57, 0.85) | <0.001** | 0.46 (0.37, 0.54) | <0.001** |

| AS | 0.75 (0.59, 0.96) | 0.022** | 0.41 (0.33, 0.51) | <0.001** |

| Risk group | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate | 1.36 (1.05, 1.76) | 0.019** | 1.20 (0.96, 1.51) | 0.112 |

| High | 1.29 (0.98, 1.72) | 0.074 | 1.07 (0.83, 1.37) | 0.610 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary school | 1 | 1 | ||

| Secondary school | 1.43 (1.17, 1.76) | <0.001** | 1.10 (0.91, 1.34) | 0.332 |

| University degree | 2.88 (2.32, 3.56) | <0.001** | 2.10 (1.72, 2.56) | <0.001** |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabitating | 1 | 1 | ||

| Single | 0.73 (0.60, 0.89) | 0.002** | 0.73 (0.61, 0.88) | <0.001** |

| SDMwish, wished shared decision making; SDMexp, Experienced shared decision-making; OR (CI), odds ratio (confidence interval); ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; RP, Radical prostatectomy; RAD, Radiotherapy; AS, Active surveillance; CRN, Cancer Registry of Norway; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; **statistically significant . | ||||

The associations were particularly strong for age and education, and less so for living with a partner. The effect size was largest for the youngest age groups and for the patients with the highest education.

When stratifying by treatment group, the association between SDMwish /SDMexp and education was particularly obvious for the AS and RAD group (Table S1a/Sb). The effect of decreasing age remained significant in the RAD and AS group for SDMwish, and in the AS group for SDMexp. Only in the RP group, partnership was significantly associated with SDMwish and SDMexp, although the effect size was similar in all the three groups. No significant associations emerged between ECOG performance status and SDMwish and SDMexp. For each treatment group, Figure S1a/Sb illustrates the absolute probabilities to report SDMwish and SDMexp stratified for different covariate patterns, combining age, education, and civil status. The considerable inter-treatment differences are clearly evident.

Discussion

In this population-based survey, 78% of men with a curatively treated PCa had wished to be involved in SDM and 83% of these men reported involvement. The proportion of patients who reported SDMwish and SDMexp was positively associated with decreasing age, increasing education, having a partner and undergoing RP. The patients’ functional status was not associated with SDMwish or SDMexp.

Prevalence of SDMwish and SDMexp

Some methodological considerations precede the interpretation of our findings. In contrast to randomized trials regarding curative treatment often performed in centers of excellence, our registry-based findings reflect real-world treatment policies in non-selected patients. It is believed that urologists, who meet the patients at diagnosis, offer RP whenever immediate local treatment is indicated and possible. RAD is more often considered in older men and if RP is not an option due to comorbidity, the patients’ refusal of RP, or if the extent of the primary tumor represents technical difficulties. As a result of the dominance of urologists in the diagnostic phase a proportion of PCa patients may never have the full option to select their treatment modality. Even in such clinical situations, however, sufficient information should be given during SDM to ensure that the patient understands the various benefits and risks associated with available treatments.

According to the available literature, preferences of SDMwish and SDMexp vary considerably among PCa patients (SDMwish; from 42% to 95% [9,12–15] and SDMexp; 69% [10]). Compared with Ihrig et al. [9] and Schaede et al. [12] our finding that one of four men did not want to be involved in SDM, suggests that a smaller portion of Norwegian men want to be involved.

With the background in the considerable inter-patient variability of SDMwish several studies highlight the need to adapt SDM to the individual patient`s characteristics and preferences [15,24,25], rather than advocating SDM for all patients. According to a Dutch study decision regret can be minimized if the content of SDM is tailored according to patients’ wishes and needs [18]. The same study concluded that all patients with localized PCa should be encouraged to be actively involved in the decision making process, regardless of their stated preferences [18]. By following this strategy, physicians should attempt to involve all patients, regardless of their SDM preference.

Drummond et al. [10], surveying 6,559 PCa survivors, reported that 58% PCa survivors experienced congruence between their actual and preferred role in the decision making, and that an incongruent experience was associated with higher levels of decisional conflict and lower post-treatment global HRQoL [10]. These findings suggest that involving patients in SDM to the degree to which they want to be involved may contribute to improved PCa survivors’ HRQoL.

Age

The demonstrated inverse association between age and SDMwish and SDMexp is in line with previous studies in PCa patients [2,9,10,17,26,27]. The relation between low age and SDM was strongest in the AS and RAD groups, which might reflect that these treatment options might be difficult to understand, especially for the older patients. This underlines that clinicians should be aware of the importance of age as to the patients’ ability to understand these two treatment options.

Treatment

On the one hand, the association between choosing RP and the wish/ or experience of SDM, is in line with previous research [10]. On the other hand, a large German study documented an association of a pre-treatment passive role in men undergoing RP [9]. Such behavior is possibly explained by the patients’ desire to have removed the cancer as quickly as possible, without considering other more time-consuming curative treatment options, such as RAD or AS. In our stratified analyses the inter-treatment differences might be explained by the patients’ understanding of the various treatment options. Many PCa patients have an inaccurate understanding of survival and disease reccurence in balance to late adverse effects [27]. The results showing significant association, in addition to high effect sizes, between SDMwish/SDMexp and decreasing age and higher education within the RAD and the AS groups, emphasizes that these treatment options might be difficult to understand. Even though AS is now the recommended treatment option for low-risk patients, research shows that many patients are not fully aware of what AS entails, and still opt for immediate active treatment [27,28].

Education

In agreement with the previous findings, increased levels of education significantly raised the number of our patients who had wished SDM [9,18,26]. van Stam et al. [27] found that prior to choosing treatment, PCa patients poorly understand the different risks associated with the disease and the various treatments. In this Dutch multicenter study they found that 45% of the patients overestimated the risk of needing definitive treatment following AS and 80% did not understand that the mortality rates following RP, RAD and AS were similar. Sixty-five percent of the patients in this study did not comprehend that, compared with RAD and AS, patients after RP are at greater risk of urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, and 61% were not aware of the increased risk of post-RAD bowel problems [27].

Marital status

Our findings that partnership is a significant factor for SDMwish and SDMexp is in contrast to previous findings that could not find any association between marital status and SDM [8]. Although marital status was only statistically significant in the RP group, the effect size in all three groups was similar. Smaller sample sizes in both the RAD and AS groups might explain the lack of statistical significance in these groups.

ECOG performance status

Contrary to our hypothesis, our analysis did not reveal an association between SDM and performance status, the latter viewed as a proxy of comorbidity. These results differ at some degree from previous findings showing that reduced health status and comorbidity decrease SDMwish and SDMexp [7]. An explanation may be that the performance status imperfectly reflects comorbidity in these generally healthy patients with an assumed life-expectancy of at least 10 years.

Strengths and limitations

There are several limitations of this study that must be acknowledged. Firstly, when dealing with survey-based self-reported data, there are concerns about low response rates and risk of selection bias, for example, that patients with more extreme perceptions could be more likely to respond. Our results showing the high preference of SDMwish and SDMexp compared with previous studies, suggests that a highly selected patient group might have responded to our survey, ultimately influencing the results. Secondly, the modest response rate of 56% might affect the generalizability of the results. Due to restrictions from the Regional Ethical Committee, we were not allowed to present data separately on invited non-responders. Based on data from the Norwegian Prostate Cancer Registry, Table S2 describes; all registered non-metastatic patients <90 years diagnosed 2017–2019, responders (n = 5,063) and the difference between all diagnosed patients and responders (n = 8,400). Furthermore, this table indicates selection bias (age > 70 years, ECOG performance status ≥1 and more history of previous cancer) (Table S2). Thirdly, using only one cross-sectional survey, possible changes over time in the patients’ view about pre-treatment SDM were not captured. Fourthly, in this registry-based study erroneous coding cannot be excluded as was the case for AS patients with high-risk tumors. The population-based real-world design is viewed as the main strength of this study.

Conclusion

One in four PCa patients eligible for curative treatment did not wish to be involved in SDM. And despite the wish to be involved, one in five men experienced not having been involved. When counselling PCa patients on benefits and risks of curative treatment modalities, particularly concerning the less intuitive options RAD and AS, physicians should be aware that age, level of education and marital status are associated with the patients’ wish and experience of involvement in SDM.

Geolocation information

This is a nationwide study, based on patient reported data from patients treated at different hospitals in Norway.

References

- [1] Cancer Registry of Norway. Cancer in Norway 2021 – cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway. 2022.[cited 2023 Feb 14]. Vailable from: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/globalassets/cancer-in-norway/2021/cin_report.pdf

- [2] Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer-2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2021;79(2):243–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.042

- [3] Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. Fifteen-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(17):1547-1558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.08.014.

- [4] Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. Patient-reported outcomes 12 years after localized prostate cancer treatment. NEJM Evid. 2023;2(4). https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDx2300122

- [5] Wollersheim BM, van Stam MA, Bosch RJLH, et al. Unmet expectations in prostate cancer patients and their association with decision regret. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(5):731–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00888-6

- [6] Meissner VH, Simson BW, Dinkel A, et al. Treatment decision regret in long-term survivors after radical prostatectomy: a longitudinal study. BJU Int. 2022;131(5):623-630. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15955

- [7] Lechner S, Herzog W, Boehlen F, et al. Control preferences in treatment decisions among older adults – results of a large population-based study. J Psychosom Res. 2016;86:28–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.05.004

- [8] Spooner K, Chima C, Salemi JL, Zoorob RJ, Self-reported preferences for patient and provider roles in cancer treatment decision-making in the United State. Fam Med Commun Health. 2017;5(1):43–55. https://doi.org/10.15212/FMCH.2017.0102

- [9] Ihrig A, Maatouk I, Friederich HC, et al. The treatment decision-making preferences of patients with prostate cancer should be recorded in research and clinical routine: a pooled analysis of four survey studies with 7169 patients. J Cancer Educ. 2022;37(3):675–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01867-2

- [10] Drummond FJ, Gavin AT, Sharp L. Incongruence in treatment decision making is associated with lower health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors: results from the PiCTure study. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1645–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3994-z

- [11] Yennurajalingam S, Rodrigues LF, Shamieh OM, et al. Decisional control preferences among patients with advanced cancer: an international multicenter cross-sectional survey. Palliat Med. 2018;32(4):870–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317747442

- [12] Schaede U, Mahlich J, Nakayama M, et al Shared decision-making in patients with prostate cancer in Japan: patient preferences versus physician perceptions. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.2016.008045

- [13] Davison BJ, Degner LF, Morgan TR. Information and decision-making preferences of men with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(9):1401–8.

- [14] Davison BJ, Gleave ME, Goldenberg SL, et al. Assessing information and decision preferences of men with prostate cancer and their partners. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25(1): 42–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002820-200202000-00009

- [15] Davison BJ, Parker PA, Goldenberg SL. Patients’ preferences for communicating a prostate cancer diagnosis and participating in medical decision-making. BJU Int. 2004;93(1):47–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04553.x

- [16] Hurwitz LM, Cullen J, Elsamanoudi S, et al. A prospective cohort study of treatment decision-making for prostate cancer following participation in a multidisciplinary clinic. Urol Oncol. 2016;34(5):233.e17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.11.014

- [17] Orom H, Biddle C, Underwood W, et al. What is a “Good” treatment decision? Decisional control, knowledge, treatment decision making, and quality of life in men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(6):714–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X16635633

- [18] van Stam MA, Pieterse AH, van der Poel HG, et al. Shared decision making in prostate cancer care-encouraging every patient to be actively involved in decision making or ensuring the patient preferred level of involvement? J Urol. 2018;200(3):582–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2018.02.3091

- [19] Hernes E, Kyrdalen A, Kvåle R, et al. Initial management of prostate cancer: first year experience with the Norwegian National Prostate Cancer Registry. BJU Int. 2010;105(6):805–11; discussion 811. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08834.x

- [20] Sørensen JB, Klee M, Palshof T, et al. Performance status assessment in cancer patients. An inter-observer variability study. Br J Cancer. 1993;67(4):773–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1993.140

- [21] Folkehelseinstituttet. Spørreskjemabanken; 2014. [cited 2022 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.fhi.no/kk/brukererfaringer/sporreskjemabanken2/

- [22] Bjertnaes OA, Sjetne IS, Iversen HH. Overall patient satisfaction with hospitals: effects of patient-reported experiences and fulfilment of expectations. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(1):39–46. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000137

- [23] Iversen HH, Holmboe O, Bjertnæs OA. The cancer patient experiences questionnaire. (CPEQ): reliability and construct validity following a national survey to assess hospital cancer care from the patient perspective. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001437. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001437

- [24] Hubbard G, Kidd L, Donaghy E. Preferences for involvement in treatment decision making of patients with cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(4):299–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2008.03.004

- [25] Brom, L, Hopmans W, Pasman HR, et al. Congruence between patients’ preferred and perceived participation in medical decision-making: a review of the literature. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-14-25

- [26] Cuypers M, Lamers RED, de Vries M, et al. Prostate cancer survivors with a passive role preference in treatment decision-making are less satisfied with information received: results from the PROFILES registry. Urol Oncol. 2016;34(11):482.e11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.06.015

- [27] van Stam MA, van der Poel HG, van der Voort van Zyp JRN, et al. The accuracy of patients’ perceptions of the risks associated with localised prostate cancer treatments. BJU Int. 2018;121(3):405–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14034

- [28] Donovan JL. Presenting treatment options to men with clinically localized prostate cancer: the acceptability of active surveillance/monitoring. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(45):191–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs030