ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Transurethral versus open enucleation of the prostate in Sweden – a retrospective comparative cohort study

Jessica Bohloka , Rajne Söderberga and Oliver Patschanb

, Rajne Söderberga and Oliver Patschanb

aSurgical Clinic, Ystad Hospital, Skåne Region, Sweden; bDepartment of Translational Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

ABSTRACT

Objective: To investigate if treatment with transurethral enucleation of the prostate (TUEP) during the learning curve is as efficient and safe in the short term as transvesical open prostate enucleation (OPE), in patients with benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) > 80 ml in a population in Sweden.

Methods: 54 patients with ultrasound verified BPO > 80 ml and indication for surgery underwent TUEP or OPE between 2013 and 2019. Peri- and postoperative outcome variables regarding voiding efficiency and morbidity from 20 OPE at Skåne University Hospital (SUS) and from the first 34 TUEP performed at SUS and Ystad Hospital were retrospectively assembled. Follow-up data from the first 6 postoperative months were collected by chart review.

Results: Intraoperative bleeding during TUEP was less than in OPE (225 ml vs. 1,000 ml). TUEP took longer surgery time than OPE (210 vs. 150 min.). Within 30 days postoperatively, bleeding occurred less often after TUEP (23% vs. 40%), requiring one fourth of the blood transfusions given after OPE. After TUEP, patients had shorter hospitalisation (3 days vs. 7 days) and catheterisation time (3 days vs. 12 days). During the 6-month follow-up period, incontinence and UTI defined as symtomatic significant bacteriuria (urinary culture) were observed as main complications after TUEP and OPE. Functional outcome data availability (International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS] questionnaire, uroflowmetry, residual urine) were limited.

Conclusions: Treatment with TUEP during the learning curve led to less bleeding, shorter hospitalisation- and catheterisation time than treatment with OPE. However, surgery time was shorter with OPE. There were no major differences between the groups concerning mid-term functional outcomes, with the reservation of an inconsistent follow-up.

KEYWORDS: Benign prostatic obstruction; transurethral enucleation of prostate; transvesical open prostate enucleation; bleeding; surgery time; functional outcomes

Citation: Scandinavian Journal of Urology 2023, VOL. 58, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.2340/sju.v58.15327.

Copyright: © 2023 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing on behalf of Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes, provided proper attribution to the original work.

Received: 26 June 2023; Accepted: 24 October 2023; Published: 8 December 2023

CONTACT Jessica Bohlok jaj_b@hotmail.com Surgical Clinic, Ystad Hospital, Skåne Region, SE 271 33 Ystad, Sweden

Competing interests and funding: The study was financed by Innovations-ALF (ALF-I, ALF = Agreement upon cooperation between the Swedish state and Swedish healthcare regions to promote medical education and research) and SUF-research grant (SUF = Swedish Urological Association).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Introduction

Benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) is a common complaint in men with increasing age and its manifestations are collected under the term LUTS (lower urinary tract symptoms) [1]. In cases where surgical intervention has been indicated, open enucleation of the prostate (OPE) has been the oldest established surgical treatment for larger prostate glands (> 80 ml) worldwide [2,3]. The adenomas are commonly enucleated either transvesically, using the index finger (Freyer procedure) [2], or through the anterior prostatic capsule (Millin procedure) [3]. The complications of open surgery include a high risk of bleeding and the subsequent need of blood transfusion, especially in patients with coagulation disorders or on anticoagulant/antiplatelet therapy [4]. In the last decades, a wider range of treatment options have evolved with the intention of minimizing the invasiveness, surgery time, hospitalisation, complications and economical costs.

Transurethral enucleation of the prostate (TUEP) using laser surgery was first described in 1998 by Fraundorfer and Gilling, initially using Holmium laser (HolEP) pulse waves [5]. It has since been performed at clinics around the world on larger prostate glands due to its´ superiority to transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) with shorter surgery time, less bleeding [6] and more beneficial urodynamic effects [7]. Comparative studies [8–12] between any form of TUEP and OPE have shown that patients undergoing TUEP had less complications, shorter hospitalisation and shorter catheterisation compared to OPE, and with equivalent clinical short-term and long-term effects. In recent studies, also referred to in the EAU-guidelines (European Association of Urology), it has been shown that energy sources currently used in transurethral enucleation, Holmium laser (HolEP), Thulium laser (ThulEP) or bipolar current (BipolEP), show no superiority to one another at any endpoint, and therefore any of above technologies can be performed with equal validity and postoperative outcome [13–18].

In Sweden, HolEP was performed for the first time in the early 2000s in Linköping. The technology did not receive enough attention to be established in the daily routine and eventually dropped out of the department’s armamentarium. In 2013, HolEP was established at Skåne University Hospital. The method was later introduced in Ystad Hospital where it is still in routine use, but with bipolar current as energy source (BipolEP). TUEP has not yet become the modality of choice in treatment of large prostatic glands in Sweden. The remaining urological clinics in Sweden still apply the OPE modality, or more recently robot-assisted simple prostatectomy (RASP), for enucleation, despite there being good evidence supporting the application of TUEP. Therefore, at the present time, no other comparative studies between OPE and TUEP have yet been conducted in Sweden.

This retrospective study seeks to compare the treatment with TUEP during the learning curve to open prostate enucleation (OPE) in patients with BPO > 80 ml in a small cohort in southern Sweden, focusing on peri- and postoperative outcome variables regarding voiding efficiency and morbidity.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients with indication for surgical treatment of BPO, and who were treated either with TUEP or OPE between 2013 and 2019 at the Department of Urology, Skåne University Hospital in Malmö or at Ystad Hospital, were included. All patients accepted to be enrolled in the study. The data were obtained by retrospective review of the patients’ charts. Two groups were formed as follows: Group 1 (n = 34): operated with TUEP (between 2013 and 2016 HolEP, between 2016 and 2019 BipolEP); group 2 (n = 20): operated with OPE. Inclusion criteria were a gland size over 80 ml and indication for surgery based on preoperative ultrasound of the prostate, International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) ≥8, a Qmax < 12 ml/s derived from uroflowmetry, or catheter carriers (indwelling or clean intermittent catheter [CIC]). Exclusion criteria were patients with prostate volume < 80 ml, patients who had previously undergone surgery in the lower urinary tract such as transurethral incision or resection of the prostate (TUIP/TURP), transurethral microwave treatment (TUMT), internal urethrotomy, patients who had pre-existing prostate or urinary bladder cancer, and symptoms not related to BPO.

Blood haemoglobin was measured preoperatively. Relevant variables that might affect the end results such as preoperative bacteriuria (urine culture), diabetes, previous stroke/TIA, and medication with anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs, were noted. Follow-up was divided into three time periods: Intraoperative, postoperative within 30 days (short-term) and postoperative up to 6 months (mid-term), focusing on different parameters of importance within each period.

Surgery

Prior to the establishment of the TUEP method at Skåne University Hospital (SUS), one of the surgeons visited four hospitals in Germany known for their expertise in transurethral enucleation (AVK Berlin, UKE Hamburg, Asklepios Hamburg Barmbek, and MHH Hannover), in order to learn the technique. HolEP was then established and performed between 2013 and 2016 at SUS in Malmö, and in 2016 the method was moved to Ystad, due to a reorganisation of SUS. Instead of HolEP, TUEP continued to be performed as BipolEP in Ystad Hospital.

All patients received thrombosis prophylaxis with standard subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin (Enoxaparin 40 mg/day) during the hospitalisation. All patients on oral anticoagulants or antiplatelets paused their treatment a few days to a week prior to surgery, depending on the type used, and received low-molecular-weight heparin up to and during the surgery and hospitalisation as a substitute until oral treatment could be continued. All patients provided a urine culture a week preoperatively, and all patients received antibiotics preoperatively, either as a course (in case of positive urine culture), or prophylactically, according to local routines and regardless of operation modality.

Patients in group 1 were treated with TUEP, either BipolEP or HolEP, using Storz® (Germany) 26 Charrière laser- or bipolar resectoscopes, performed by two different experienced urologists, both learning the TUEP technique. In all cases of TUEP, a morcellator (Storz®) was used to remove the enucleated tissue from the urinary bladder. Saline solution was used during the surgeries. The HolEP procedure is described by Fraundorfer and Gilling [5], using the two-lobe technique. In this study, HolEP was performed using a LUMENIS® 100 Watt Powersuite (Israel) with a 550 µm fiber. The BipolEP technique is described in detail by Giulianelli et al. [19]. In this study, an enucleation loop (Storz®) was used for BipolEP instead of a bipolar button.

Patients in group 2 were treated with open enucleation of the prostate (OPE) through a transvesical approach, performed by 11 different experienced urologists. After removal of the prostate adenoma, the bladder neck was sutured with a running suture using Vicryl 3-0. The bladder was sutured in two layers with Biosyn 3-0 (Covidien®). The abdominal wall was closed with running sutures with PDS 1-0 in the fascia and Vicryl 3-0 (Ethicon®) subcutaneously, as well as with metal clips in the skin. All patients had an 18 Charrière wound drainage with the tip in the preperitoneal space, which was removed when there was no more fluid flow.

Patients from both groups had a 22 Charrière 3-way urinary catheter postoperatively for as long as the surgeon deemed it to be necessary.

Surgery time, anaesthesia time, the weight of enucleated adenoma tissue, bleeding amount, and any intraoperative complications according to standard routines were recorded. On the 1:st postoperative day, blood haemoglobin was measured. During the postoperative course within 30 days, observations were made about the time for catheter removal and length of hospitalisation, use of pain medication and any adverse events according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [20]. After discharge from the hospital, patients were planned to be followed up for a measurement of uroflowmetry, residual urine and IPSS questionnaire within the first 6 months postoperatively.

Endpoints

The primary endpoints were intraoperative bleeding, number of blood transfusions, surgery time, length of hospitalisation and catheterisation. Secondary endpoints were postoperative complications within 30 days according to Clavien-Dindo, and functional outcome within 6 months measured by IPSS, uroflowmetry and residual urine, and any complicating event occurring including unplanned readmission to the hospital. Incontinence was defined as any signs of urinary leakage with or without effort either notified directly to the clinic or via IPSS. UTI was defined as symptoms notified to the clinic and verified by urine cultivation.

Statistics

All data was handled and deidentified after collection. The intra- and perioperative outcomes were computed using either median or mean values. Median was calculated for non-normally distributed variables, and the mean was calculated for normally distributed values.

The p-value was calculated using the Student´s T-test for normally distributed parameters. For non-normally distributed values, a Mann–Whitney U test was used. Microsoft Excel and R were used as software. For the primary endpoint (intraoperative bleeding) a multivariate analysis with a logarithmic model was used. The model was modified, so that a patient with no bleeding was calculated as bleeding 1 ml (to avoid log(0)=inf). A p-value of 0.01 or lower was considered to indicate statistical significance.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (Dnr. 2013/286 and 2014/483).

Results

Intraoperative results

54 patients, who were operated on with either TUEP or OPE between 2013 and 2019, were included in the study. Patients from both groups had comparable preoperative conditions and comorbidity (Table 1a). Preoperatively, patients operated with TUEP were more often using a catheter (indwelling or CIC) than patients operated with OPE (24/34 vs. 9/20). In about half of the non-catheterised patients, preoperative residual urine, uroflowmetry, IPSS, lists of drinking and micturition patterns, were not measured. Whether a preoperative cystometry was performed or not, was not registered.

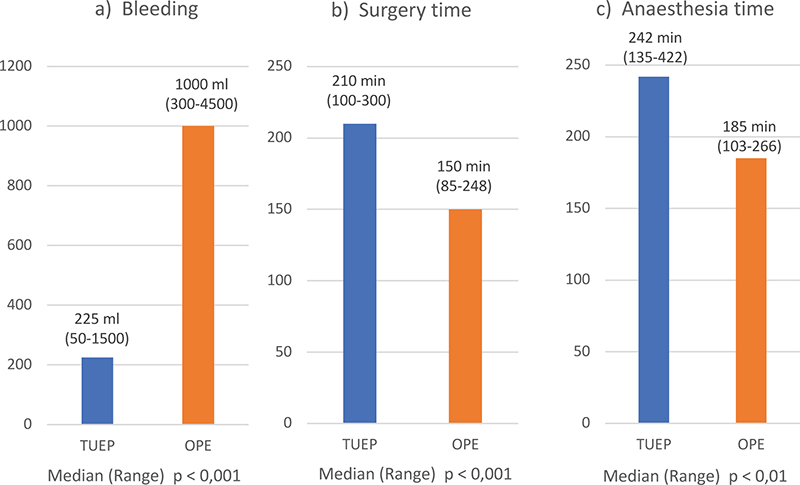

Intraoperative bleeding during OPE was significantly higher than during TUEP (Table 1b, Figure 1a). Median surgery time (Figure 1b) and anaesthesia time (Figure 1c) were slightly longer with TUEP than with OPE.

Figure 1a-c. Intraoperative data; a: Median bleeding in ml; b: Median surgery time in minutes; c: Median anaesthesia time in minutes. Blue colour = TUEP, n=34; orange colour = OPE, n=20.

Short-term results

Within 30 days postoperatively, haematuria occurred in 23% (8/34) of the patients after TUEP compared to 40% (8/20) after OPE. This in turn resulted in a lower postoperative blood haemoglobin value on day 1, and a higher need for blood transfusions in patients operated with OPE (Table 2). Patients operated with TUEP also had nearly half the hospitalisation time and a quarter of the catheterisation time compared to OPE (Table 2). Only about one third of the patients operated with TUEP needed pain medication containing opioids (in this study Oxycodone per orally was used), whereas almost all (95%) of the patients operated with OPE needed those. Comparative data of complications according to Clavien-Dindo are seen in Table 2.

Mid-term results

During the mid-term follow-up period (up to 6 months), incontinence and UTI were observed as main complications both after TUEP and OPE, although data from IPSS questionnaire and uroflowmetry were limited. Four of the patients in Group 1 who did not fill in the IPSS questionnaire informed the clinic via telephone that they were satisfied with the functional results after the surgery. The remaining patients in that group either did not respond to be followed up or did not receive any information from the clinic. A statistical analysis of the follow-up data seemed to be inadequate, since the number of patients was too low (Table 3). In group 1, nine out of 34 TUEPs led to enucleation of only one lobe of the prostate due to technical difficulties and long surgery time, which may have affected the functional results.

Discussion

During the learning curve, in this study, TUEP appeared to be a safe procedure with short- and mid-term results were comparable to those seen in other studies focusing on transurethral enucleation [13–18]. Compared with OPE, patients operated with TUEP had shorter catheterisation time, half of the hospitalisation time and less bleeding, the latter resulting in far fewer blood transfusions. The need for treatment of pain with opioids was significantly lower in patients operated with TUEP than in patients treated with OPE. In times where patient satisfaction and surgery quality count high, and where healthcare resources are limited, this is a considerable improvement compared to OPE.

The learning curve data presented in this study demonstrate that implementation of TUEP is feasible, safe, and has improved the quality of care for patients with BPO > 80 ml. TUEP may be available in all urological clinics that perform transurethral surgery, although BipolEP is less expensive and may be easier to learn than HolEP. Learning TUEP means to learn the concept of anatomical endoscopic enucleation of the prostate (AEEP). AEEP is likely to contribute to the better understanding of the prostatic anatomy. Based on the experiences from this study, the authors find good reasons to encourage the implementation of TUEP and the concept of AEEP in every urological clinic in Sweden.

The somewhat longer surgery time and anaesthesia time for patients operated with TUEP might in part be explained by the fact that the surgeons were learning the technique. Previous studies have shown that performing TUEP during the learning curve led to satisfactory results, even without mentors. It was estimated that about 25–50 operations were needed, with a slightly steeper learning curve when using Holmium laser instead of bipolar current [21–25]. With this information in mind, none of the surgeons had progressed past the learning curve at the time this study was conducted. Another time-consuming moment during TUEP is the removal of the adenoma through the urethra. A morcellator was used in this study. Another common method of tissue removal is to use bipolar resection technique on the enucleated adenoma still being adherent to the bladder neck. However, these two removal methods do not seem to differ in terms of time efficiency [12,26–28].

Patients from both groups had similar health conditions preoperatively. Complications, classified according to Clavien-Dindo within 30 days postoperatively, showed that most patients after TUEP and OPE had complications belonging to class 1 and 2 such as fever or UTI requiring antibiotics, bleeding with or without blood transfusions, urinary urgency and/or incontinence. After OPE, a slightly higher number of patients were seen with complications of class 3b (bleeding requiring re-operation under general anaesthesia) than after TUEP. The fact that 20 OPEs were performed by 11 different urologists may also have contributed to the relatively high bleeding rate in patients in this group, as none of these surgeons could possibly have had the chance to develop sufficient skills to prevent bleeding in this rather infrequently performed operation. However, the frequency of complications in this study is in line with that of other published data [29–31].

As the follow-up data up to 6 months were not complete, no statistical evaluation of the complications and the functional results could be made. However, it is noteworthy that within 6 months, eight out of 23 patients had complaints with incontinence after TUEP. The grade of incontinence could not be specified from the patients’ charts, but the low bother score might indicate that it was mild incontinence that was experienced. These complaints were expressed orally, noticed by the urologist or nurse in the patients’ charts, but were not verified or quantified with, for example, a pad test. Otherwise, there seemed to be no major differences between the groups regarding functional aspects within 6 months, which is in line with results from other studies comparing TUEP and OPE [29–31].

It is remarkable that follow-up was not more consequent, where only around 1/3 of the OPE and 2/3 of the TUEP patients had some kind of follow-up data registered in the patient charts. This may be explained by limited healthcare resources for benign diseases in Sweden, but it may also be an expression of a temporary lack of clear routines, which in turn may be a consequence of the reorganisation of the urological clinic carried out during the study period. Another limitation of the study is its retrospective nature, which might have led to a selection bias. Also, OPE was performed by a significantly higher number of surgeons than TUEP, which may have led to a contributor bias. Even considering that all those surgeons were experienced, it cannot be excluded that some of those were less experienced than others, which may have led to a greater variation in intra- and postoperative results in this group. Finally, the small group size contributed to a limited validity of the generated data.

In summary, treatment with TUEP during the learning curve led to less bleeding, shorter hospitalisation and catheterisation time than treatment with OPE, for the cost of a somewhat longer surgery time. There were no major differences between the groups concerning mid-term functional outcomes, with the reservation of an inconsistent follow-up. The data from this study indicate, that implementation of TUEP has the potential to improve quality of care for patients with BPO > 80 ml compared to OPE, even during the learning curve.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Sascha Ahyai, Dr. Axel Böhme, Prof. Andreas Gross, and Prof. Thomas R.W. Herrmann for the excellent demonstrations of the transurethral enucleation technique. Without their knowledge and effort this work would not have been possible. We also want to express our gratitude to Mads B. Raad, PhD, who made the multivariate calculations.

ORCID

Jessica Bohlok  https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5669-4749

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5669-4749

Oliver Patschan  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5788-794X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5788-794X

References

- [1] Thomas AW, Cannon A, Bartlett E, et al. The natural history of lower urinary tract dysfunction in men: minimum 10-year urodynamic followup of transurethral resection of prostate for bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2005 Nov;174(5):1887–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000176740.76061.24

- [2] Freyer PJ. A clinical lecture on total extirpation of the prostate for radical cure of enlargement of that organ: with four successful cases: delivered at the Medical Graduates’ College, London, June 26th. Br Med J. 1901 Jul 20;2(2116):125–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.2116.125

- [3] Millin T. Retropubic prostatectomy; a new extravesical technique; report of 20 cases. Lancet. 1945 Dec 1;2(6380):693–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(45)91030-0

- [4] Herrmann TR, Bach T, Imkamp F, et al. Thulium laser enucleation of the prostate (ThuLEP): transurethral anatomical prostatectomy with laser support. Introduction of a novel technique for the treatment of benign prostatic obstruction. World J Urol. 2010 Feb;28(1): 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-009-0503-0

- [5] Fraundorfer MR, Gilling PJ. Holmium:YAG laser enucleation of the prostate combined with mechanical morcellation: preliminary results. Eur Urol. 1998;33(1):69–72. https://doi.org/10.1159/000019535

- [6] Ahyai SA, Chun FK, Lehrich K, et al. Transurethral holmium laser enucleation versus transurethral resection of the prostate and simple open prostatectomy – which procedure is faster? J Urol. 2012 May;187(5):1608–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2011.12.107

- [7] Gilling PJ, Mackey M, Cresswell M, et al. Holmium laser versus transurethral resection of the prostate: a randomized prospective trial with 1-year followup. J Urol. 1999 Nov;162(5):1640–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68186-4

- [8] Kuntz RM, Lehrich K, Ahyai SA. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus open prostatectomy for prostates greater than 100 grams: 5-year follow-up results of a randomised clinical trial. Eur Urol. 2008 Jan;53(1):160–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.08.036

- [9] Moody JA, Lingeman JE. Holmium laser enucleation for prostate adenoma greater than 100 gm.: comparison to open prostatectomy. J Urol. 2001 Feb;165(2):459–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005392-200102000-00025

- [10] Wei HB, Guo BY, Tu YF, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of transurethral laser versus open prostatectomy for patients with large-sized benign prostatic hyperplasia: a meta-analysis of comparative trials. Investig Clin Urol. 2022 May;63(3):262–72. https://doi.org/10.4111/icu.20210281

- [11] Rao JM, Yang JR, Ren YX, et al. Plasmakinetic enucleation of the prostate versus transvesical open prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia > 80 mL: 12-month follow-up results of a randomized clinical trial. Urology. 2013 Jul;82(1):176–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2013.02.032

- [12] Geavlete B, Stanescu F, Iacoboaie C, et al. Bipolar plasma enucleation of the prostate vs Open prostatectomy in large benign prostatic hyperplasia cases – a medium term, prospective, randomized comparison. BJU Int. 2013 May;111(5):793–803.

- [13] Herrmann TRW, Gravas S, de la Rosette JJ, et al. Lasers in transurethral enucleation of the prostate-do we really need them. J Clin Med. 2020 May 10;9(5):1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051412

- [14] Herrmann TR. Long-term outcome after endoscopic enucleation of the prostate: from monopolar enucleation to HoLEP and from HoLEP to EEP. Urologe A. 2016 Nov;55(11):1446–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00120-016-0245-8

- [15] Gu C, Zhou N, Gurung P, et al. Lasers versus bipolar technology in the transurethral treatment of benign prostatic enlargement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. World J Urol. 2020 Apr;38(4):907–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-019-02852-1

- [16] Li J, Cao D, Huang Y, et al. Holmium laser enucleation versus bipolar transurethral enucleation for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia, which one is better? Aging Male. 2021 Dec;24(1):160–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13685538.2021.2014807

- [17] Che X, Zhou Z, Chai Y, et al. The efficacy and safety of holmium laser enucleation of prostate compared with bipolar technologies in treating benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials. Am J Mens Health. 2022 Nov-Dec;16(6):15579883221140211.

- [18] Cornu JN, Ahyai S, Bachmann A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic obstruction: an update. Eur Urol. 2015 Jun;67(6):1066–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.017

- [19] Guilianelli R, Gentile B, Albanesi L, et al. Bipolar button transurethral enucleation of prostate in benign prostate hypertrophy treatment: a new surgical technique. Urology 2015. 86:407–14.

- [20] Mitropoulos D, Artibani W, Biyani CS, et al. Validation of the Clavien-Dindo grading system in urology by the European Association of Urology guidelines ad hoc panel. Eur Urol Focus. 2018 Jul;4(4): 608–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2017.02.014

- [21] Shah HN, Mahajan AP, Sodha HS, et al. Prospective evaluation of the learning curve for holmium laser enucleation of the prostate. J Urol. 2007 Apr;177(4):1468–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.091

- [22] Jeong CW, Oh JK, Cho MC, et al. Enucleation ratio efficacy might be a better predictor to assess learning curve of holmium laser enucleation of the prostate. Int Braz J Urol. 2012 May-Jun;38(3):362–71; discussions 372.

- [23] Gürlen G, Karkin K. Does Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) still have a steep learning curve? Our experience of 100 consecutive cases from Turkey. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2021 Dec 20;93(4):412–7. https://doi.org/10.4081/aiua.2021.4.412

- [24] Feng L, Song J, Zhang D, et al. Evaluation of the learning curve for transurethral plasmakinetic enucleation and resection of prostate using a mentor-based approach. Int Braz J Urol. 2017 Mar-Apr;43(2):245–55.

- [25] Xiong W, Sun M, Ran Q, et al. Learning curve for bipolar transurethral enucleation and resection of the prostate in saline for symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: experience in the first 100 consecutive patients. Urol Int. 2013;90(1):68–74. https://doi.org/10.1159/000343235

- [26] Neill MG, Gilling PJ, Kennett KM, et al. Randomized trial comparing holmium laser enucleation of prostate with plasmakinetic enucleation of prostate for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2006 Nov;68(5):1020–4.

- [27] Zhang K, Sun D, Zhang H, et al. Plasmakinetic vapor enucleation of the prostate with button electrode versus plasmakinetic resection of the prostate for benign prostatic enlargement > 90 ml: perioperative and 3-month follow-up results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Urol Int. 2015;95(3):260–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000381753

- [28] Li K, Wang D, Hu C, et al. A novel modification of transurethral enucleation and resection of the prostate in patients with prostate glands larger than 80 ml: surgical procedures and clinical outcomes. Urology. 2018 Mar;113:153–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.11.036

- [29] Li M, Qiu J, Hou Q, et al. Endoscopic enucleation versus open prostatectomy for treating large benign prostatic hyperplasia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 31;10(3):e0121265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121265

- [30] Lin Y, Wu X, Xu A, et al. Transurethral enucleation of the prostate versus transvesical open prostatectomy for large benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Urol. 2016 Sep;34(9):1207–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-015-1735-9

- [31] Gratzke C, Schlenker B, Seitz M, et al. Complications and early postoperative outcome after open prostatectomy in patients with benign prostatic enlargement: results of a prospective multicenter study. J Urol. 2007 Apr;177(4):1419–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.062