ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Diagnostic accuracy and safety of renal tumour biopsy in patients with small renal masses and its impact on treatment decisions

Bassam Mazin Hashima , Abbas Chabokb,c

, Abbas Chabokb,c , Börje Ljungbergd

, Börje Ljungbergd , Erland Östberge

, Erland Östberge and Farhood Alamdaria

and Farhood Alamdaria

aDepartment of Urology, Region Västmanland – Uppsala University, Center for Clinical Research, Västmanland Hospital Västerås, Västerås, Sweden; bCentre for Clinical Research, Region Västmanland/Uppsala University, Västerås, Sweden; cDivision of Surgery, Danderyd University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden; dDepartment of Diagnostics and Intervention, Urology and Andrology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden; eDepartment of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Region Västmanland – Uppsala University, Centre for Clinical Research, Västmanland Hospital Västerås, Västerås, Sweden

Abstract

Objective: To assess the safety and diagnostic accuracy of renal tumour biopsy (RTB) in patients with small renal masses (SRM) and to assess if RTB prevents overtreatment in patients with benign SRM.

Material and methods: In a retrospective, single-centre study from Västmanland, Sweden, 195 adult patients (69 women and 126 men) with SRM ≤ 4 cm who had undergone RTB during 2010–2023 were included. The median age was 70 years (range 23–89). The sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of RTB were calculated using the final diagnosis as the reference standard. Treatment outcomes were recorded for a median 42-month follow-up. Complications following the biopsies were assessed according to the Clavien–Dindo system.

Results: The overall sensitivity of RTB was 95% (95% confidence interval [CI] 90% – 98%) and specificity was 100% (95% CI 95% – 100%). The positive predictive value was 100% and negative predictive value was 92%. The rate of agreement between RTB and the final diagnosis measured using kappa statistics was 0.92. Of the 195 patients, 62 underwent surgery and 48 were treated with ablation. The concordance rate between the RTB histology and final histology after surgery was 89%. Treatment was withheld in 67 of 195 patients with a benign or inconclusive RTB. No patients developed renal cell carcinoma or metastasis during follow-up. Complications occurred in two patients that were classified with Clavien–Dindo grades I and IV.

Conclusions: Percutaneous renal tumour biopsy appears to be a safe diagnostic method that provides accurate histopathological information about small renal masses and reduces overtreatment of benign SRM.

KEYWORDS Renal tumour biopsy; small renal masses; renal tumour biopsy; percutaneous renal biopsy; renal cell carcinoma; oncocytoma

Citation: Scandinavian Journal of Urology 2024, VOL. 59, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.2340/sju.v59.40844.

Copyright: © 2024 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing on behalf of Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material, with the condition of proper attribution to the original work.

Received: 22 May 2024; Accepted: 21 August 2024; Published: 11 September 2024

CONTACT Börje Ljungberg borje.ljungberg@umu.se Department of Diagnostics and Intervention, Urology and Andrology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

Introduction

The incidence of small renal masses (SRM) has increased in the past decades [1–3], likely because of the ageing population and increased use of imaging investigations [1–4]. It is estimated that more than half of all renal masses are discovered incidentally [2, 4]. In most cases, it is not possible to differentiate between benign and malignant renal masses using current imaging modalities. In contrast to most other solid tumours, renal masses are not routinely subjected to biopsy and histopathological analysis before treatment. The European Association of Urology (EAU) recommends renal tumour biopsy (RTB) before ablative treatment, in candidates for active surveillance and before systemic treatment in cases involving metastatic disease [5]. The growing occurrence of SRM creates a challenge for treatment decisions because of the risks of overtreating benign tumours and undertreating malignant ones [6].

Recent publications have indicated that RTB provides highly accurate histopathological data about SRM, reduces overtreatment of benign renal masses, and may aid urologists in the choice of management [7–11]. Despite the promising data in earlier publications, there remains a need for more detailed follow-up data for patients with SRM who have benign or inconclusive biopsies. It is imperative to investigate the long-term outcomes in patients with benign or inconclusive biopsies to improve the understanding of the clinical significance and potential limitations of RTB as a diagnostic method in SRM.

The aims of this study were to evaluate the safety and diagnostic accuracy of RTB in patients with SRM and to assess whether RTB influenced treatment decisions and reduced overtreatment.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study included all patients diagnosed with SRM (Identified by the International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10 code D.41) who also underwent RTB between 2010 and 2023 in Region Västmanland, Sweden, which has a catchment area of 270,000 inhabitants. Among the 219 patients identified, 26 were excluded because their biopsies were conducted for reasons other than SRM, such as renal masses >4 cm or cystic tumours. Two of the remaining 193 patients had two RTBs on different occasions and were counted as a separate case. The patients’ median age was 70 years (23–89 years), and 69 women and 126 men were included.

All patients were managed in the Department of Urology in Region Västmanland. The records, clinical notes, imaging studies, histopathological data and cause of death on the certificates for all patients were reviewed. The data collected included patient age, gender, renal mass size, number of biopsies, treatment given, results of histopathological examination of the RTB and specimens after surgery and follow-up data.

The RTBs were performed by clinical radiologists who used ultrasonic or computed tomography (CT) guidance and with a 16- or 18-gauge needle. A needle length of 15, 20, or 25 cm was used according to each patient’s body composition. Three cores with a length of 9 mm were taken from each lesion. The coaxial technique was used when the biopsies were performed under CT guidance. Most biopsies were performed using ultrasound guidance and a non-coaxial technique. The biopsies were taken after premedication with oxazepam (5 mg) and ketobemidone (5 mg) 30 min before the procedure and under local anaesthesia with 10 mL lidocaine (10 mg/mL) and adrenaline (5 μg/mL). After the procedure, the patient remained in a supine position for 4 h and was observed for an additional 2 h before being discharged. The observation included monitoring of blood pressure, pulse and body temperature, and inspection of the puncture site.

Biopsy specimens were analysed by pathologists at the same hospital. The analysis included descriptions of the shape, number and size of the specimens. Pathologists also determined whether the specimens were viable and representative. They analysed the tissue origin and contents of the specimens, such as perirenal fat, renal capsule and normal renal tissue. When applicable, they described the tumour type according to the 2022 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification [12]. Prognostic factors such as the presence of necrosis, rhabdoid, or sarcomatoid differentiation were identified and, in cases of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) or papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC), grading was performed according to the International Society of Urological Pathology standards. The analysis was based on histopathological features and immunohistochemical markers; in some cases, molecular analysis aided in the diagnosis.

Follow-up

Patients with a malignant histology identified by RTB were followed up according to the recommendations of the EAU guidelines. All 193 patients were followed up through a retrospective review of the medical charts, physician notes, radiological examinations and any diagnosis codes up to 14 years after the RTB; the median follow-up was 3.5 years.

Statistics

The sensitivity and specificity of the RTB were calculated by comparing the histopathology of the RTB to the final diagnosis determined by the histopathological examination of the surgical specimen. In patients who did not undergo surgery, the final diagnosis was established clinically and via follow-up. This final diagnosis served as the reference standard for statistical calculation of the sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. The comparison between the results of RTB and the final diagnosis produced a kappa value. The agreement was regarded as poor for κ ≤ 0.2, fair for κ of 0.21–0.4, moderate for κ of 0.41–0.60, good for κ of 0.61–0.8, and very good for κ > 0.80. All statistical data were analysed with the help of a statistician using the MedCalc® [13] statistical software to calculate the sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and kappa values.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

Results

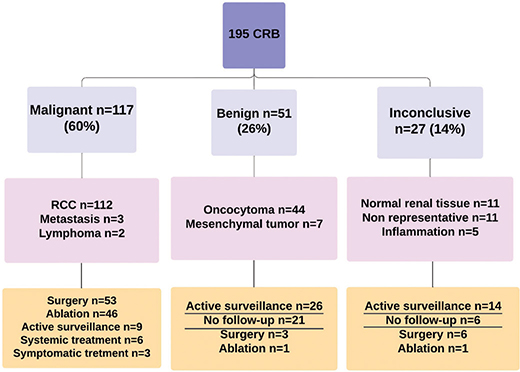

In total, 193 patients underwent 195 RTBs. The demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The initial RTB histology were malignant in 104 biopsies (53%), benign in 50 (26%), and inconclusive results in 41 biopsies (21%). Subsequent re-biopsies were performed in 25 patients. An overview of the histological results following the RTBs, and re-biopsies is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Summary of the results of the first and second RTBs and their management. Treatment was withheld from 67 patients (underscored) because of non-malignant RTB. RTB: renal tumour biopsy; RCC: Renal cell carcinoma.

Of the 117 RTBs with malignant histology, 112 were RCCs and 5 other malignant lesions. Of these, 53 underwent surgery, and 2 had a re-biopsy. The findings from the surgery and re-biopsy aligned with the initial malignant diagnoses in all cases, but in one patient in which a primary pRCC on the RTB, a ccRCC was diagnosed in the final histology of the surgical specimen. The biopsy findings and management of the 117 patients with malignant histology are detailed in Figure 1.

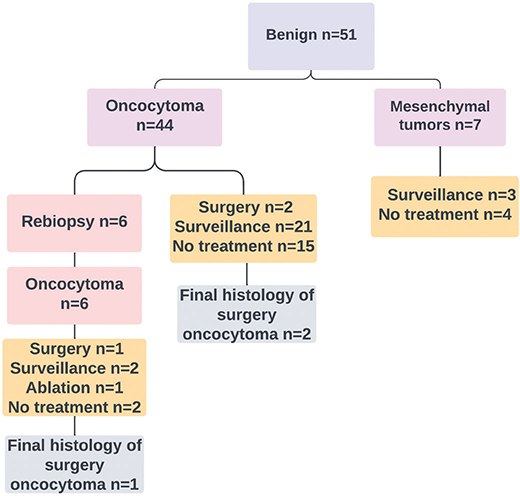

Among the 51 patients with benign histology, 44 had oncocytoma and 7 had mesenchymal tumours, including angiomyolipoma. Among 8 patients with oncocytoma, 6 underwent a re-biopsy, whereas 3 patients underwent surgery. The histology of the re-biopsies and surgeries reaffirmed the initial diagnosis of oncocytoma in all these 8 patients. The biopsy findings and management of the group with benign RTBs are illustrated in Figure 2. In total, 26 patients with benign RTBs went under active surveillance, during which the rate of tumour growth was ≤ 4 mm per year. Another 21 patients did not undergo active treatment or follow-up, and none within this group were diagnosed with RCC or metastasis at the ending of this study.

Figure 2. Histological results of the benign biopsies and their management.

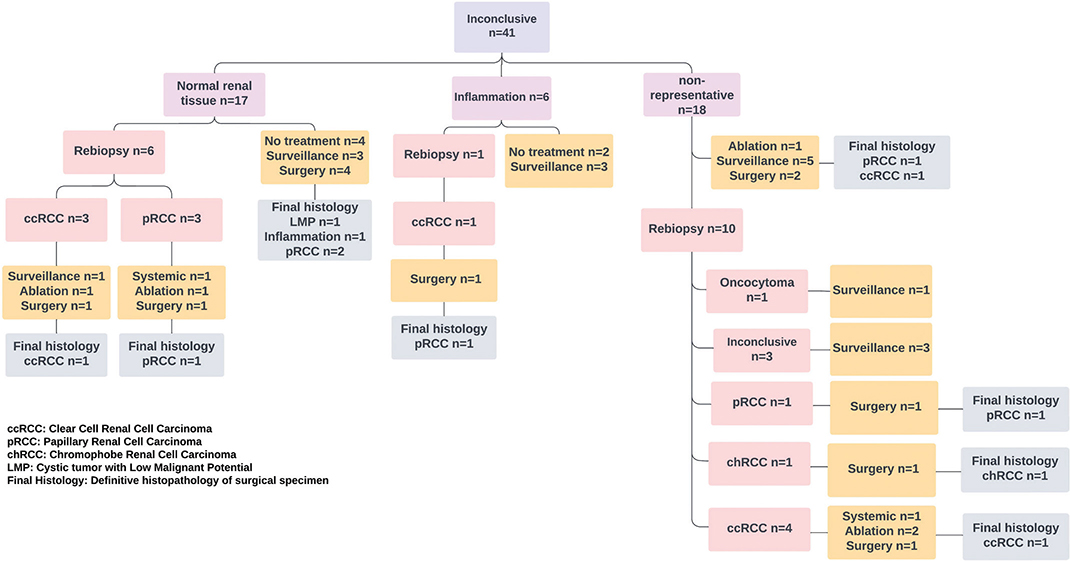

Of the 41 patients with an inconclusive first RTB, 17 underwent a re-biopsy. The re-biopsy was diagnostic in 14 (82%) patients, 13 with RCC and 1 with oncocytoma, while 3 RTBs remained inconclusive. The findings from the 41 initially inconclusive RTBs are detailed in Figure 3. For 6 patients with an inconclusive first RTB who did not undergo a re-biopsy, subsequent surgery revealed 5 with malignant and 1 with benign histology. Fourteen patients with an inconclusive RTB were followed with active surveillance, during which tumour growth was 2 mm per year. Six patients did not receive active treatment or surveillance, and none of these were diagnosed with RCC or metastasis during the follow-up.

Figure 3. Results of the 41 initially inconclusive RTBs, 14 re-biopsies, and their management. RTB: renal tumour biopsy.

Diagnostic accuracy and impact on treatment decision

The overall sensitivity and specificity of RTB were 95% (95% confidence interval [CI] 90–98) and 100% (95% CI 95–100), respectively. The positive predictive value was 100%, and the negative predictive value was 92%. Surgery was performed in 62 patients, and the concordance rate between the histology of the RTB and final histology was 89%. The rate of agreement between RTB and the final diagnosis, measured using the kappa statistic, was κ = 0.92. Treatment was withheld in 67 patients with benign or inconclusive RTB (Figure 1).

Complications

Complications occurred in two patients (1%). One patient developed a haemothorax caused by accidental injury to the intercostal vessels (Clavien–Dindo grade IV). The second patient developed a self-limiting subcapsular haematoma (Clavien–Dindo grade I).

Use of RTB over time

During the early phase of the study (2010–2016), a total of 42 RTBs were performed. During the late study period (2017–2023), this number increased to 153. No relationship was observed between the year of biopsy and the diagnostic accuracy of the RTB (data not shown).

Discussion

This study showed that percutaneous RTB was a safe diagnostic method that provided valuable histopathological information about SRMs. The results of RTB reduced overtreatment in a substantial proportion of patients. The sensitivity and concordance of RTB with the final diagnosis were improved significantly when a re-biopsy was performed following an initial inconclusive RTB. This improvement in diagnostic yield stresses the value of re-evaluating inconclusive RTB results, especially when considering that a substantial proportion of these biopsies indicated malignancy.

The sensitivity and specificity findings in this study agree with those from a systematic review and meta-analysis done by Marconi et al. [10] That review summarised data from 57 studies that included 5,228 patients and demonstrated a high sensitivity (99.1%) and specificity (99.7%) of RTB along with a low complication rate (8.1%). These results were confirmed in a meta-analysis done by He et al., who reported a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 100% for RTB along with a low complication rate [8]. He et al. also found that, following an inconclusive biopsy, 56% of repeat biopsies indicated a malignant histology. We found similar results – sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 100% for RTB for identifying renal malignancies and a complication rate of 1%. The low complications rate in our study was consistent with the those of Tolouee et al. having an overall complication rate following RTB of 2.1% [14].

Our study has addressed the challenge of inconclusive RTBs. We found that conducting a re-biopsy following an inconclusive initial biopsy significantly increased the diagnostic yield, in that the re-biopsies were diagnostic in 82% of cases. This observation is consistent with the findings of a literature review by Laguna et al., that a re-biopsy revealed malignancy in 71% of initially inconclusive biopsies [15]. Our findings may help to guide clinicians in the management of patients with inconclusive RTB results. We emphasise the critical role of a repeat biopsy in unmasking malignancies among the inconclusive biopsies and thereby help to prevent the potential undertreatment of renal cancers.

In a large retrospective study from a Canadian centre, 529 patients with SRMs underwent a RTB. The initial biopsy was diagnostic in 90% of cases, and the diagnostic yield improved to 94% following a re-biopsy. Treatment could be avoided in 26% of cases because of benign histology [11]. Similarly, we found that the initial biopsy was diagnostic in 79% of cases and that the diagnostic yield improved to 86% following the re-biopsy. In our study, treatment was avoided in 34% of cases, which is consistent with the results of the aforementioned Canadian study.

The use of RTB at our clinic increased throughout the study period. This increase paralleled the findings in a previous retrospective study from Canada, which included 933 patients with SRMs and also showed a gradual increase in RTB utilisation over time [16].

The added value in our study is its aim to assess the diagnostic accuracy of RTB obtained from SRM ≤ 4 cm. Evaluating the precision of RTB in clinical T1a renal tumours is important because up to one-third of these small masses are benign and could be spared from unnecessary treatment [2, 6, 7, 9, 17–19]. A retrospective, multicentre study of 11,529 patients compared the rate of benign histology of resected renal tumours between the United States of America (USA) and Korea. The rate of benign histology among resected SRMs was 19.5% in the USA and 7.6% in Korea. This disparity may be partly attributed to urologists’ and patients’ attitudes regarding SRMs and a more prudent approach to surgical treatment of SRMs in Korea [19]. This significant difference suggests an overestimation of malignancy risk in SRMs in the USA. By highlighting the safety and diagnostic accuracy of RTB, our study stresses the importance of incorporating RTB into the diagnostic pathway as a step towards a more cautious and individualised treatment stance.

In contrast to the EAU guidelines that propose the selective use of RTB [5], the Canadian Association of Urology and The Kidney Cancer Research Network of Canada suggest that RTB should be considered routinely in patients with SRM before management. These guidelines also recommend giving patients information about RTB and including them in shared decision-making. In cases of inconclusive biopsy results, the patient should be counselled on the benefits and harms of a repeat biopsy [20, 21]. The evidence presented in the present study supports such an approach. A RTB should be avoided in patients with advanced age and significant comorbidity, for whom treatment options remain limited and symptomatic regardless of the biopsy results. In such cases, a biopsy exposes the patient to potential complications, discomfort and anxiety without altering the treatment course. We emphasise the importance of individualised and judicious decision-making, and adherence to the principles of Choosing Wisely [22].

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design and the relatively small cohort size may limit the generalisability of the findings. Secondly, the follow-up for patients with benign and inconclusive biopsies was conducted through an analysis of patient charts, radiological examinations, ICD codes and physicians’ notes, each of which may introduce biases associated with retrospective data collection. Thirdly, the relatively limited follow-up time is furthermore a limitation of the results.

Conclusions

The current study shows that RTB was a safe diagnostic method that provided accurate histopathological information about SRM. The sensitivity of RTB increased when a re-biopsy was performed in patients with an inconclusive first biopsy. The results of RTB improved treatment decisions and reduced overtreatment for a substantial proportion of patients.

ORCID

Bassam Mazin Hashim  0009-0006-8775-9774

0009-0006-8775-9774

Chabok, Abbas  0000-0001-9662-5045

0000-0001-9662-5045

Börje Ljungberg  0000-0002-4121-3753

0000-0002-4121-3753

Erland Östberg  0000-0002-7449-3907

0000-0002-7449-3907

Farhood Alamdari  0000-0003-3589-7789

0000-0003-3589-7789

References

- [1] Kjellman A, Lindblad P, Lundstam S et al. Predictive characteristics for disease recurrence and overall survival in non-metastatic clinical T1 renal cell carcinoma – results from the National Swedish Kidney Cancer Quality Register Group. Scand J Urol. 2023;57(1–6):67–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681805.2022.2154383

- [2] Thorstenson A, Harmenberg U, Lindblad P, et al. Impact of quality indicators on adherence to National and European guidelines for renal cell carcinoma. Scand J Urol. 2016;50(1):2–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/21681805.2015.1059882

- [3] Key statistics about kidney cancer. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/kidney-cancer/about/key-statistics.html [cited 13 October 2022].

- [4] Vasudevan A, Davies RJ, Shannon BA, et al. Incidental renal tumours: the frequency of benign lesions and the role of preoperative core biopsy. BJU Int. 2006;97(5):946–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06126.x

- [5] Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Abu-Ghanem Y, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2022 update. Eur Urol. 2022;82(4):399–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2022.03.006

- [6] Johnson DC, Vukina J, Smith AB, et al. Preoperatively misclassified, surgically removed benign renal masses: a systematic review of surgical series and United States population level burden estimate. J Urol. 2015;193(1):30–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.102

- [7] Londoño DC, Wuerstle MC, Thomas AA, et al. Accuracy and implications of percutaneous renal biopsy in the management of renal masses. Perm J. 2013;17(3):4–7. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-110

- [8] He Q, Wang H, Kenyon J, et al. Accuracy of percutaneous core biopsy in the diagnosis of small renal masses (≤4.0 cm): a meta-analysis. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41:15–25. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.04

- [9] Wang R, Wolf JS, Wood DP, et al. Accuracy of percutaneous core biopsy in management of small renal masses. Urology. 2009;73(3):586–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2008.08.519

- [10] Marconi L, Dabestani S, Lam TB, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of percutaneous renal tumour biopsy. Eur Urol. 2016;69(4):660–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.072

- [11] Richard PO, Jewett MAS, Bhatt JR, et al. Renal tumor biopsy for small renal masses: a single-center 13-year experience. Eur Urol. 2015;68(6):1007–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.004

- [12] Moch H, Amin MB, Berney DM, et al. The 2022 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs – part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol. 2022;82(5):458–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2022.06.016

- [13] Schoonjans F. MedCalc’s diagnostic test evaluation calculator. MedCalc. Available from: https://www.medcalc.org/calc/diagnostic_test.php [cited 2 December 2023].

- [14] Tolouee SA, Madsen M, Berg KD, et al. Renal tumor biopsies are associated with a low complication rate. Scand J Urol. 2018;52:407–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681805.2018.1524397

- [15] Laguna MP, Kümmerlin I, Rioja J, et al. Biopsy of a renal mass: where are we now? Curr Opin Urol. 2009;19(5):447–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0b013e32832f0d5a

- [16] Couture F, Finelli T, Breau RH, et al. The increasing use of renal tumor biopsy amongst Canadian urologists: when is biopsy most utilized? Urol Oncol. 2021;39(8):499.e15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.05.026

- [17] Lim A, O’Neil B, Heilbrun ME, et al. The contemporary role of renal mass biopsy in the management of small renal tumors. Front Oncol. 2012;2:106. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2012.00106

- [18] Frank I, Blute ML, Cheville JC, et al. Solid renal tumors: an analysis of pathological features related to tumor size. J Urol. 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2217–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000095475.12515.5e

- [19] Jeong CW, Han JH, Byun SS, et al. Rate of benign histology after resection of suspected renal cell carcinoma: multicenter comparison between Korea and the United States. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:216. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-11941-3

- [20] Richard PO, Violette PD, Bhindi B, et al. Canadian Urological Association guideline: management of small renal masses. Can Urol Assoc J. 2022;16(2):E61–75. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.7763

- [21] Lavallée LT, McAlpine K, Kapoor A, et al. Kidney Cancer Research Network of Canada (KCRNC) consensus statement on the role of renal mass biopsy in the management of kidney cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2019;13(12):377–83. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.6176

- [22] Born KB, Levinson W. Choosing Wisely campaigns globally: a shared approach to tackling the problem of overuse in healthcare. J Gen Fam Med. 2018;20(1):9–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgf2.225