ORIGINAL REPORT

Clinical Characterization and Treatment Response of Folliculitis Decalvans Lichen Planopilaris Phenotypic Spectrum: A Unicentre Retrospective Series of 31 Patients

Ana MELIÁN-OLIVERA1,2, Óscar M. MORENO-ARRONES1,2, Patricia BURGOS-BLASCO1,2, Ángela HERMOSA-GELBARD1,2, Pedro JAÉN-OLASOLO1,2, Sergio VAÑÓ-GALVÁN1,2 and David SACEDA-CORRALO1,2

1Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain and 2Trichology Unit, Grupo de Dermatología Pedro Jaén, Madrid, Spain

Folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum has been described as a form of cicatricial alopecia. The aim of this study is to describe the clinical and trichoscopic features and therapeutic management of this condition in a series of patients. A retrospective observational unicentre study was designed including patients with folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum confirmed with biopsy. A total of 31 patients (20 females) were included. The most common presentation was an isolated plaque of alopecia (61.3%) in the vertex. Trichoscopy revealed hair tufting with perifollicular white scaling in all cases. The duration of the condition was the only factor associated with large plaques (grade III) of alopecia (p = 0.026). The mean time to transition from the classic presentation of folliculitis decalvans to folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum was 5.2 years. The most frequently used treatments were topical steroids (80.6%), intralesional steroids (64.5%) and topical antibiotics (32.3%). Nine clinical relapses were detected after a mean time of 18 months (range 12–23 months). Folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum is an infrequent, but probably underdiagnosed, cicatricial alopecia. Treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs used for lichen planopilaris may be an adequate approach.

SIGNIFICANCE

Folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum is a rare, but probably underdiagnosed, presentation of cicatricial alopecia. It deserves a careful correlation between clinical, trichoscopic and histopathological features. This study includes 31 patients with folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum and provides relevant data related to clinical and trichoscopic characteristics. The presence of a single cicatricial patch on the vertex with trichoscopic signs of lichen planopilaris and hair tufting of 6 or more hair shafts should raise the suspicion of a folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum diagnosis. The treatment is not well defined, but the use of therapies for classical lichen planopilaris seems to be an adequate approach.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2024; 104: adv12373. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v104.12373.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Submitted: Apr 23, 2023; Accepted: Jan 10, 2024; Published: Feb 19, 2024

Corr: Sergio Vañó-Galván, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain. Carretera Colmenar Viejo km 9.100, ES-28034 Madrid, Spain. E-mail: drsergiovano@gmail.com

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

INTRODUCTION

Folliculitis decalvans (FD) is an uncommon form of neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia. The hair loss and concomitant symptoms (pruritus and pain) cause a significant negative impact in patients’ quality of life (1). Trichoscopy may help to detect this condition, and histopathological analysis confirms the diagnosis (2, 3). There is no specific treatment, although oral antibiotics, oral isotretinoin and intralesional steroids may be useful to attain clinical remission (4).

Occasionally, FD may share clinical and histological characteristics with lichen planopilaris (LPP) (5). It implies a significant diagnostic challenge and deserves a careful correlation between clinical, trichoscopic and histopathological features (6). Recent publications have described small case series of patients with this entity, and the term “FD and LPP phenotypic spectrum” (FDLPPPS) was proposed recently (7). However, the idea of spectrum of FD/LPP is still debatable and several authors consider that this clinical presentation may be the result of LPP-like changes in late FD (5).

The aim of this study was to describe the clinical and trichoscopic characteristics, and therapeutic management in a series of patients diagnosed with FDLPPPS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective study was designed including patients diagnosed with FD between 2010 and 2021 at the Trichology Unit in Hospital Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, Spain, who finally met criteria for FDLPPPS. To confirm the diagnosis of FDLPPPS it was necessary to have a well-recorded personal history of FD with histopathological confirmation in all cases and an objective change to LPP-like clinical features, according to Yip et al.’s criteria (5), and trichoscopic features.

Data were collected regarding epidemiology, clinical presentation (size, number, shape and location of alopecic patches, presence of pustules, yellow crusts, polytrichia and concomitant pityriasis amiantacea), time to FDLPPPS presentation since previous diagnosis of FD, symptoms, trichoscopic findings (hair tufting of 2–5 hairs or > 6 hairs, perifollicular erythema, perifollicular scaling, interfollicular scaling, follicular haemorrhages, white dots, vascular patterns and others) and therapeutic options.

Data relating to treatment (total of therapies used, treatments received 3 months before the first presentation of FDLPPPS clinical features, response to treatment and side-effects detected) and time to relapse were also analysed.

To stratify the severity of FDLPPPS, this study applied the same approach that was used for FD (3 grades according to the maximum diameter of the largest patch of alopecia; grade I: < 2 cm, II: 2–4.99 cm, III: 5 cm or more) (8). The onset of FDLPPPS was considered when they showed clinical (and trichoscopic) features of this entity and no inflammatory flare-ups for a year. Relapses were considered in either 3 situations: progression of the alopecia was observed, clinical inflammatory flare-up (pustules, exudative crusts with or without symptoms) and trichoscopic features of activity (2 points or more in the FD Activity Scale) (2).

Statistical analysis

After data gathering statistical analysis was performed. For categorical variables, frequencies were reported. For continuous variables, mean and range were calculated. The relationship between epidemiological, clinical and trichoscopic features and severity groups was analysed. To assess the statistical significance of differences observed between groups, we performed an univariate analysis using the χ2 and Mann–Whitney U tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. All tests were 2-sided and statistical significance was considered with p < 0.05. For all statistical analyses, the statistical software package SPSS (Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used.

RESULTS

A total of 31 Caucasian patients (20 females and 11 males) with a median age of 40 years (range 23–66 years) were recruited. None of the patients had a family history of FD or LPP. The median age of onset of the condition was 34 years (range 22–51 years). The associated dermatological comorbidities were: androgenetic alopecia (17 patients, 54.8%), seborrhoeic dermatitis on the scalp (9 patients, 29.0%), atopic dermatitis in 2 patients and vulvar lichen sclerosus in 1 patient.

Clinically, 19 patients (61.3%) presented a unique plaque of alopecia on the scalp and 12 patients (38.7%) had 2 or more areas affected (Fig. 1). The most common location was the vertex (in 27 patients, 87.1%), followed by parietal area (12 patients, 38.7%), occipital area (5 patients, 16.1%) and the frontal area (2 patients, 6.5%). The mean size of the area affected was 20.6 cm2 (range 1–187 cm2). Three patients (9.7%) had a grade I extension of alopecia, 11 patients (35.5%) grade II, and 17 patients (54.8%) grade-III. An oval or round shape was the most frequent clinical presentation (18 patients, 58.0%), followed by diffuse hair loss in 8 patients (25.8%), a multifocal patchy hair loss in 3 patients and a large wedge-shaped plaque of alopecia in 2 patients. At the time of the shift to LPP-like features, all patients presented polytrichia, 7 patients associated isolated clinical characteristics of FD (6 patients had yellowish crusts and 1 patient follicular pustules) and 4 patients had concomitant pityriasis amiantacea. Pruritus was referred by 14 patients (45.2%) and trichodynia by 3 patients (9.7%).

Fig. 1. Clinical presentation of folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum. A unique cicatricial plaque of alopecia with hair tufts of 6 or more hair follicles.

Trichoscopy revealed hair tufting and perifollicular white scaling in all cases (Fig. 2) (the remaining tricho-scopic features are summarized in Table I).

Fig. 2. Trichoscopy of folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum. Loss of follicular openings and hair tufting. White perifollicular scales and ingrowing hairs are visible.

After statistical analysis, the duration of the condition was the only factor associated with grade III forms of FDLPPPS (p = 0.026). The presence of white dots on trichoscopy was higher in grade I–II cases than in severe forms of the disease (p = 0.015). No other clinical factors were correlated with the severity of the disease.

Once the diagnosis of FDLPPPS was established, the patients were followed for a mean of 2.9 years (range 1–9 years). A total of 18 patients (58.1%) changed over to the FDLPPPS spectrum during the follow-up in our department, and 13 patients (41.9%) had received a previous diagnosis of FD in another dermatological centre. The mean time since the first diagnosis of FD was 5.2 years (range 1–22 years). Treatments used before and after the first presentation of FDLPPPS spectrum and during it are shown in Table SI. In 1 patient, no treatment was started, as he referred stabilization of his alopecia for 2 years. The side-effects recorded were 2 cases of gastrointestinal discomfort due to oral doxycycline and 5 cases with temporary scalp atrophy due to intralesional steroids. None of the side-effects was severe enough to discontinue treatment.

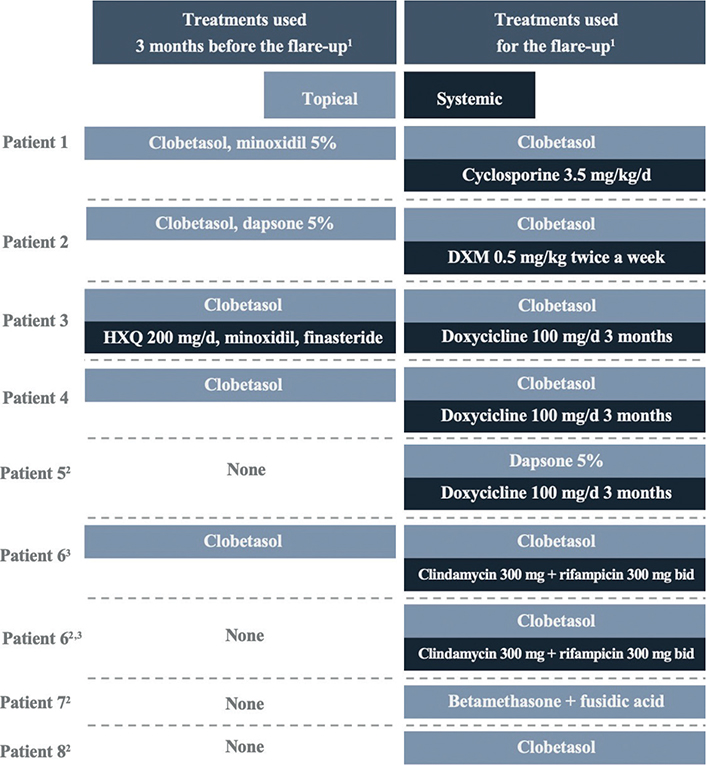

A total of 9 relapses of FDLPPPS were detected in 8 patients (25.8%) during follow-up. All of these patients presented inflammatory clinical signs in isolated areas of the alopecia plaque, except for 1 patient who had a generalized FD flare-up. The flare-ups took place after a mean time of 18 months (range 12–23 months) since FDLPPPS diagnosis. Four of those relapses occurred after an interruption of the medical treatment (all of them only with topical treatment) for a mean time of 8 months due to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. The treatments that patients were receiving before the flare-up, and to treat the flare-up, are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Treatments received by patients before and during the flare-up. HXQ: hydroxychloroquine; DXM: dexamethasone; bid: twice a day. 1All patients also received intralesional steroids. 2Four patients discontinued medical treatment due to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. 3One patient experienced 2 relapses.

DISCUSSION

As highlighted in previous studies, FDLPPPS is a not uncommon presentation for dermatologists specializing in conditions affecting the hair. Trüeb et al. (9) were the first to report on the bi-phasic nature of FD based on their sequential dermoscopic observations in FD. Yip et al. (5) described this clinical presentation in 13 patients for the first time in 2019, Egger et al. (7) studied 7 patients shortly after, and Müller-Ramos et al. (10) described 2 paediatric cases. However, some case reports describing patients with clinical overlap between LPP and FD (11–13) suggest that clinicians might encounter FDLPPPS cases more often than currently believed. To our knowledge, this study describes the largest series of FDLPPPS in the literature to date.

Regarding clinical features, the most common presentation of FDLPPPS was a single plaque on the vertex, a finding also observed in previous studies. The presence of a single cicatricial patch on the vertex with trichoscopic signs of LPP and hair tufting of 6 or more hair shafts should raise the suspicion of a FDLPPPS diagnosis. According to the severity-scale of FD, most of the cases of FDLPPPS included in this study were grade III. Both characteristics support the hypothesis that most of the cases of FDLPPS are presentations of long-term FD in chronic stages. In fact, this “LPP-like” clinical presentation is rather a manifestation of a final common pathway seen in diverse scarring alopecias, including FD (5). It is important to take this into account, to avoid misdiagnosis and therapeutic errors by confusion with primary LPP, whose immunological differences have been demonstrated (14). As Trüeb et al. (9) proposed, the development of features of LPP with time may be due to the disruption of hair follicles in the course of the bacterial infection, with consecutive exposure of follicular antigens ultimately giving rise to autoimmunity targeting the hair follicle at critical sites. In addition, there are other clinical presentations that are different in distribution (multifocal or diffuse) and location (parietal or occipital area). These situations may reflect a disruption of the follicular immune-privilege on the whole scalp, that it has been also demonstrated in other cicatricial alopecias (15, 16).

The scarce symptoms associated with this condition are also notable. Pruritus was found in less than the half of our patients and trichodynia in only 3 cases. This is much less frequent than symptoms associated with FD (68% of the patients have associated pruritus and 30% trichodynia).

The use of oral antibiotics in FD is controversial due to increasing antibiotic resistance (17); in our series, most of the patients were taking oral doxycycline or the combination of oral clindamycin and rifampicin. Both options have demonstrated to induce a significant improvement in FD during 4.8–7.2 months, respectively (8, 18). Oral antibiotics could be necessary to induce a prolonged remission in acute stages of FD that, at some point, is followed by a definitive change to the chronic lichenoid stages of FDLPPPS.

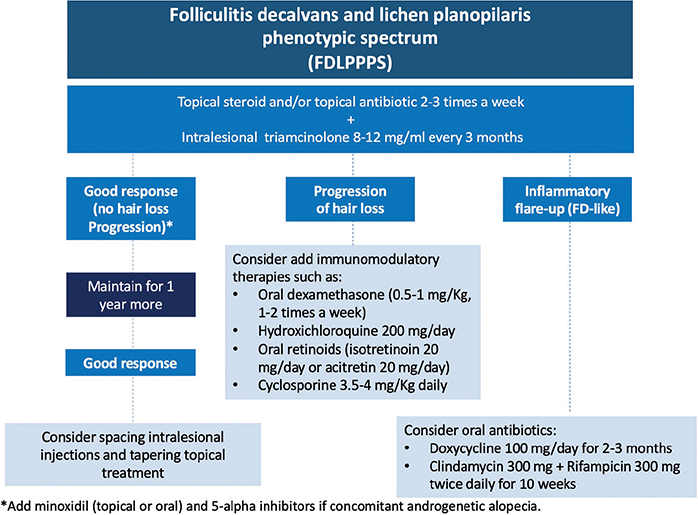

The treatment may be different once the FDLPPPS is established. Recent investigations have shown that the role of Staphylococcus aureus might be less relevant in FDLPPPS forms, and anti-inflammatory treatments should be prioritized (19). In the current study, the options most used were topical and intralesional steroids, followed by topical antibiotics. The oral treatment is not well defined, but immunomodulatory therapeutic options are used more often (e.g. oral isotretinoin, hydroxychloroquine, dexamethasone and cyclosporine). In our experience, FDLPPPS is easier to control than the FD or the LPP classical forms, which means a better prognosis for patients in this stage. The authors propose a therapeutic approach in Fig. 4 that combines those used in FD and classic LPP, based on the degree of inflammatory activity and the course of alopecia. The low number of cases of reactivation of FD do not allow further analysis. However, the treatment in those patients was almost stopped and totally interrupted in 4 cases.

Fig. 4. Proposal of therapeutic algorithm for folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum (FDLPPPS). This therapeutic algorithm is a proposal by the authors.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the retrospective design of the study might entail loss of some relevant data. It is likely that some patients were missed, who had visited our department during the previous decade, as there was no knowledge about this clinical presentation. Secondly, it was not possible to assess the efficacy of the treatment in stopping the progression of the alopecia. However, it was possible to identify information useful for clinicians, such as the therapeutic approaches used in clinical practice that might avoid new inflammatory outbreaks.

Conclusion

FDLPPPS is a rare, but probably underdiagnosed, presentation of cicatricial alopecia that should be suspected in patients with long-standing classical FD with clinical and trichoscopic changes to LPP, or in patients with concomitant features of both entities. Most of the cases in the current study were the result of chronic FD after several courses of medical therapies, frequently with oral antibiotics. The treatment is not well defined, but the use of therapies for classical LPP seems to be an adequate approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Alberto Ramírez-Follarat, MD, Psychologist, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain.

This research has been approved by Institutional Review Board IRYCIS at Ramón y Cajal Hospital, in Madrid (ID CI-BIOB-037-01). The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publication of their case details.

REFERENCES

- Pindado-Ortega C, Saceda-Corralo D, Miguel-Gómez L, Buendía-Castaño D, Fernández-González P, Moreno-Arrones OM, et al. Impact of folliculitis decalvans on quality of life and subjective perception of disease. Skin Appendage Disord 2018; 4: 34–36.

- Saceda-Corralo D, Moreno-Arrones OM, Rodrigues-Barata R, Rubio-Lombraña M, Mir-Bonafé JF, Morales-Raya C, et al. Trichoscopy activity scale for folliculitis decalvans. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e55–e57.

- Harries MJ, Trueb RM, Tosti A, Messenger AG, Chaudhry I, Whiting DA, et al. How not to get scar(r)ed: pointers to the correct diagnosis in patients with suspected primary cicatricial alopecia. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160: 482–501.

- Miguel-Gómez L, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Molina-Ruiz A, Martorell-Calatayud A, Fernández-Crehuet P, Grimalt R, et al. Folliculitis decalvans: effectiveness of therapies and prognostic factors in a multicenter series of 60 patients with long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 79: 878–883.

- Yip L, Barrett TH, Harries MJ. Folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum: a case series of bi-phasic clinical presentation and theories on pathogenesis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2020; 45: 63–72.

- Matard B, Cavelier-Balloy B, Assouly P, Reygagne P. It has the erythema of a lichen planopilaris, it has the hyperkeratosis of a lichen planopilaris, but it is not a lichen planopilaris: about the “lichen planopilaris-like” form of folliculitis decalvans. Am J Dermatopathol 2021; 43: 235–236.

- Egger A, Stojadinovic O, Miteva M. Folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum: a series of 7 new cases with focus on histopathology. Am J Dermatopathol 2020; 42: 173–177.

- Vañõ-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Arias-Santiago S, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Folliculitis decalvans: a multicentre review of 82 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol 2015; 29: 1750–1757.

- Trüeb RM, Rezende HD, Diaz MFRG. Dynamic trichoscopy. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 877–878.

- Ramos PM, Melo DF, Lemes LR, Alcantara G, Miot HA, Lyra MR, et al. Folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum: case report of two paediatric cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: e674–e676.

- Morais KL, Martins CF, Anzai A, Valente NYS, Romiti R. Lichen planopilaris with pustules: a diagnostic challenge. Skin Appendage Disord 2018; 4: 61–66.

- Rezende HD, Dias MFRG, Kempf W, Treüb RM. Linear circumscribed scleroderma-like folliculitis decalvans: yet another face of a protean condition. Int J Trichology 2018; 10: 175–179.

- Lobato-Berezo A, González-Farré M, Pujol RM. Pustular frontal fibrosing alopecia: a new variant within the folliculitis decalvans and lichen planopilaris phenotypic spectrum? Br J Dermatol 2022; 186: 905–907.

- Eyraud A, Milpied B, Thiolat D, Darrigade AS, Boniface K, Taïeb A, et al. Inflammasome activation characterizes lesional skin of folliculitis decalvans. Acta Derm Venereol 2018; 98: 570–575.

- Doche I, Romiti R, Hordinsky MK, Valente NS. “Normal-appearing” scalp areas are also affected in lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia: an observational histopathologic study of 40 patients. Exp Dermatol 2020; 29: 278–281.

- Pindado-Ortega C, Perna C, Saceda-Corralo D, Fernández-Nieto D, Jaén-Olasolo P, Vañó-Galván S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: histopathological, immunohistochemical and hormonal study of clinically unaffected scalp areas. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e84–e85.

- Asfour L, Harries M. Folliculitis decalvans in the era of antibiotic resistance: microbiology and antibiotic sensitivities in a tertiary hair clinic. Int J Trichology 2020; 12: 193–194d.

- Powell JJ, Dawber RPR, Gatter K. Folliculitis decalvans including tufted folliculitis: clinical, histological and therapeutic findings. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140: 328–333.

- Moreno-Arrones OM, Campo R del, Saceda-Corralo D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Ponce-Alonso M, Serrano-Villar S, et al. Folliculitis decalvans microbiological signature is specific for disease clinical phenotype. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 85: 1355–1357.