ORIGINAL REPORT

Effects of a Brief Mindfulness-based Intervention in Patients with Psoriasis: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Markus ECKARDT1, Laura STADTMÜLLER1, Christoph ZICK2, Jörg KUPFER1 and Christina SCHUT1

1Institute of Medical Psychology, University of Gießen, Germany and 2Department of Dermatology, Rehabilitation Clinic Borkum Riff, Borkum, Germany

Mindfulness is a special type of attention, namely focusing on the current moment in a non-judgmental manner. Extensive mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to have positive effects in patients with psoriasis. However, it is unclear whether brief (2-week) interventions are also beneficial. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a 2-week mindfulness-based intervention in patients with psoriasis. Patients were randomly assigned to an experimental (treatment-as-usual + mindfulness-based intervention) or control group (treatment-as-usual) during their clinic stay. All variables were measured by self-report using validated questionnaires: primary outcomes were mindfulness and self-compassion, secondary outcomes were itch catastrophizing, social anxiety, stress and skin status. Variables were assessed prior to, immediately and 3 months after the intervention. Effects were tested by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Analyses of pre-post-measurements (n = 39) revealed a significant interaction effect on self-reported mindfulness [F(1,35) = 7.46, p = 0.010, η2p = 0.18] and a tendency to a significant effect on self-reported self-compassion [F(1,36) = 3.03, p = 0.090, η2p = 0.08]. There were no other significant effects, but most descriptive data were in favour of the experimental group. However, the control group showed a greater improvement in skin status. Further studies are needed to replicate these findings and investigate which subgroups especially profit from such an intervention.

Key words: clinical trial; pruritus; psoriasis; psychodermatology; mindfulness.

SIGNIFICANCE

Studies have shown positive effects of extensive mindfulness-based interventions in patients with psoriasis, but it remains unclear whether 2-week mindfulness-based interventions are also beneficial in this patient group. This randomized controlled trial investigated the effects of a brief mindfulness-based intervention on mindfulness, self-compassion, itch catastrophizing, social anxiety, stress and skin status in patients with psoriasis, all measured by self-report using validated questionnaires. Positive effects on mindfulness occurred. However, the control group showed a greater improvement in skin status than the intervention group. Further studies should investigate which subgroups of patients especially profit from this type of intervention.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2024; 104: adv18277. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v104.18277.

Copyright: © Authors. Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Submitted: Jul 21, 2023; Accepted: Jan 25, 2024; Published: Apr 19, 2024

Corr: Christina Schut, Institute of Medical Psychology, Justus-Liebig University Gießen, Klinikstraße 29, DE-35392 Gießen, Germany. E-mail: Christina.Schut@psycho.med.uni-giessen.de

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition affecting approximately 2.5% of the German population (1). It is associated with itch in most patients (2). Patients with psoriasis are more prone to depression and anxiety than the general population (3).

Mindfulness is defined as purposeful and non-judgmental attention directed to the present moment (4). It can be trained through mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) (5), such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (5, 6) or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (7). Positive effects of mindfulness practice on anxiety, depression, burnout, quality of life, stress and distress have been shown in healthy subjects, and changes in mindfulness and self-compassion were identified as potential effect mechanisms (5). Other studies found positive effects of MBIs in patients with social anxiety (8), chronic pain (9) or depression (10). MBIs usually last 8 weeks (6, 7), but recent studies suggest that brief MBIs may also have positive effects (11–14). A meta-analysis defined MBIs with a duration of 2 weeks or less as brief. They were shown to have positive effects on negative affectivity (15). In patients with dermatological conditions, certain facets of mindfulness are negatively associated with itch catastrophizing (16), skin-related shame, (social) anxiety and depression and positively associated with quality of life (17).

These results indicate that patients with psoriasis could also profit from MBIs. In fact, studies solely including patients with psoriasis showed positive effects of a MBI on skin-related parameters, such as the severity of psoriasis (18–20) and the rate of skin clearing during phototherapy (21). Some studies also revealed positive effects on psychological outcome parameters (e.g. anxiety, depression or quality of life) (18, 19), while others did not (21, 22).

In summary, past research has primarily shown that extensive MBIs represent a beneficial add-on in the treatment of patients with psoriasis (18–21) and that brief 2-week MBIs have positive effects in various groups and on various parameters (11, 12). As shorter MBIs can easily be integrated into clinical practice, it is of interest to investigate its effects in the group of patients with psoriasis.

The aim of this randomized controlled trial (RCT) was to analyse whether a brief MBI leads to more self-reported mindfulness and self-reported self-compassion in comparison with treatment-as-usual (TAU) during a stay at a clinic for patients with chronic diseases. In addition, effects on the self-reported secondary outcome variables itch catastrophizing, social anxiety, stress and severity of psoriasis were investigated in an explorative manner (23). Thus, mindfulness and self-compassion were regarded as essential working mechanisms of a MBI. The secondary outcome parameters represent aspects shown to be associated with burden in patients with psoriasis, that had been linked to mindfulness in previous studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Procedure

Patients with psoriasis participating in a special tertiary prevention programme for dermatological patients were recruited at Clinic Borkum Riff, Borkum, Germany. Such programmes are offered to patients with chronic illnesses to help them to cope with their disease in a more functional way and to restore their ability to return to work. They are paid by the Deutsche Rentenversicherung (German pension insurance). Data collection took place during 3 time-periods (August – October 2019; March 2020; July – August 2020) and was conducted by 2 of the authors (ME and LS) and a student assistant. The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic strongly affected recruitment. Data were collected as part of a larger research project, also investigating interest in participation in a brief psychological intervention in addition to TAU (t0; “study 1a”) (23, 24). Patients, who reported interest in a psychological intervention and subsequently provided written informed consent were included in the current study. They were randomized, to either the experimental (EG; TAU + MBI) or control group (CG; TAU) by staff not involved in data collection or analysis. For randomization purposes cards were drawn randomly out of 2 different pots, with 1 pot containing the pseudonymized patient code and the other containing cards labelled with either EG or CG. Due to recruitment difficulties, it was decided to conduct block randomization in case fewer than 4 patients were recruited per week. This led to unequal sample sizes in the groups. Data collection was stopped after the third recruiting period due to persisting recruitment difficulties. Neither the course facilitators nor the patients were blinded to group allocation.

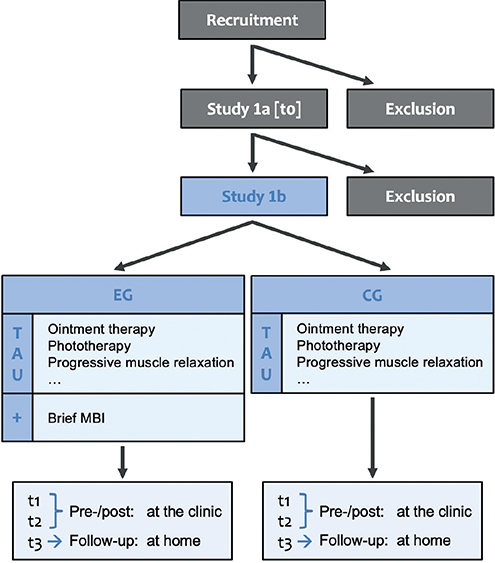

TAU comprised various therapies, such as medical treatments, phototherapy and progressive muscle relaxation (PMR). As participation in PMR was considered a possible confounding factor, patients were stratified regarding this variable in addition to sex. Dependent variables were assessed 1 week before (t1) and after the MBI (t2; short-term effects). Medium-term effects were assessed by questionnaire in a 3-month follow-up, when patients had returned home (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Study procedure. After assessment for eligibility (study 1a; t0), patients were randomly assigned to the experimental group or the control group. Both groups received treatment-as-usual (TAU) at the dermatological clinic. TAU encompassed a broad range of therapies including e.g. ointment therapy, phototherapy and progressive muscle relaxation. EG: experimental group; CG: control group; MBI: mindfulness-based intervention.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were included if they were 18–65 years old, diagnosed with psoriasis according to ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision) criteria at least 6 months previously, had symptoms of psoriasis during the last 6 months, and sufficient German language skills to answer the questionnaires. Patients were excluded if they had epilepsy, cognitive impairment e.g. due to dementia, severe mental illness (meaning severe affective and anxiety disorders, psychosis, temporary dissociative states) (25) or another itchy skin disease than psoriasis. Due to recruitment difficulties, the last exclusion criterion was modified during the process of the study, so that patients with another itchy skin disease in addition to psoriasis (n = 11) were included if the other dermatological condition did not affect their everyday life more than psoriasis.

Variables

Independent variable: mindfulness-based intervention. The brief MBI consisted of 8 sessions lasting 45–60 min each. These were conducted during 2 consecutive weeks. Each session focussed on different aspects of mindfulness and included mindfulness-based exercises, such as the body scan or mindful perception of breath. In addition, patients were encouraged to exercise mindfulness outside the group sessions. The training was conducted by a psychologist (BSc) with extensive experience (more than 5 years) in mindfulness meditation and meditative bodywork (ME) or an experienced mindfulness and insight meditation teacher (Julia Harfensteller, SAGE Institute for Mindfulness and Health, Berlin). Detailed information regarding the intervention are published (23).

Dependent variables. All dependent variables were assessed by self-report using validated questionnaires. Mindfulness was assessed by the Comprehensive Inventory of Mindfulness Experiences (CHIME), consisting of 37 items to be answered on a scale from 1 (“almost never”) to 6 (“almost always”). These can be categorized into 8 subscales (26).

Self-compassion was measured by the German short-form of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-D), comprising 12 items to be answered on a 5-point Likert Scale from 1 (“very rarely”) to 5 (“very frequently”) (27, 28).

Itch catastrophizing was measured by the itch catastrophizing subscale of the Itch-Cognition-Questionnaire (ICQ) (29) to be answered on a 5-point Likert Scale, ranging from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“always”).

Social anxiety was measured with the Fear of Negative Evaluation Questionnaire (short scale; FNE-K), consisting of 12 items to be answered on a 5-point Likert Scale, ranging from 1 =”completely does not characterise myself” to 5 =”is extremely typical for me” (30).

Stress was assessed by the Perceived Stress Scale 10 (PSS-10), comprising 10 items to be answered on a 5-point Likert Scale, ranging from to 0 =”never” to 4 =”very often” (31). In the original questionnaire, the relevant timeframe is 1 month. For this study, it was adapted to 1 week to detect possible changes due to the MBI.

Skin-related measures. Severity of psoriasis was measured by the Self-Administered Psoriasis Area and Severity index (SAPASI), which assesses the extent of affected skin areas and the intensity of the symptoms redness, thickness and scaliness using visual analogue scales (32). Scores can range from 0 to 72: 0 refers to having no psoriasis symptoms, a score > 0 and ≤ 3 refers to mild, a score > 3 and ≤ 15 refers to moderate and a score > 15 refers to severe psoriasis (33).

Further variables. Demographic variables, itch intensity and data on received treatments during the stay at the clinic were additionally assessed. Data regarding the adherence and voluntary engagement in mindfulness practice when returned home are shown in Tables SI and SII.

Data analysis

An a-priori analysis using G*Power (34) indicated that a sample-size of n = 54 is needed to detect small-to-medium-sized interaction effects (f = 0.175) by a repeated-measures ANOVA with within-between interaction (α = 0.05, 1–β = 0.8, number of groups = 2, number of measurements = 3). Group allocation (EG vs CG) was used as between-subject factor and measurement time-point (t1, t2, t3) as within-subject factor. The study aimed to recruit 60 patients to compensate for potential dropouts.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 27 (35). Repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted to test effects of the MBI on the dependent variables.

Data were screened for missing items and outliers. When persons had too many missing items according to the author recommendations, the relevant measurement time-point was excluded from analysis. If there was no definition for critical amount of missing items in the test manuals, the maximum amount of missing items allowed was set to 10% (36). In case of single missing items, sum scores were divided by the number of valid items and the mean item score was used in the analyses. Scores deviating more than 3 standard deviations (SD) from the mean were regarded as outliers and excluded from all analyses. Baseline-comparisons regarding the dependent variables and potential control variables were conducted using χ2 tests in case of nominal variables and t-tests for independent groups in case of continuous variables.

Repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted after having checked that the requirements for this statistical method were met (37). When the assumption of sphericity was violated and the Greenhouse-Geiser-Epsilon was greater than 0.75, Huynh-Feldt-correction was used. Partial eta square (η2p) was used as effect size, indicating small (0.01 < η2p), medium (0.06 < η2p) or large (0.14 < η2p) effects (38).

Dropout rate, especially at t3, was higher than expected and not all patients who were assigned to the MBI participated in all sessions. Therefore, per-protocol (PP) analyses were conducted (PP; including patients who participated in at least 7/8 group sessions) in addition to the intention-to-treat analysis (ITT). Separate analyses were conducted for short- and medium-term effects, which led to different sample sizes in the different analyses.

In contrast, all patients were included in the ITT analyses. Here, missing items were imputed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. Results of these analyses are presented in Appendix S1.

Trial registration

The study was pre-registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS; trial registration number: DRKS00017429; https://drks.de/search/de/trial/DRKS00017429).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

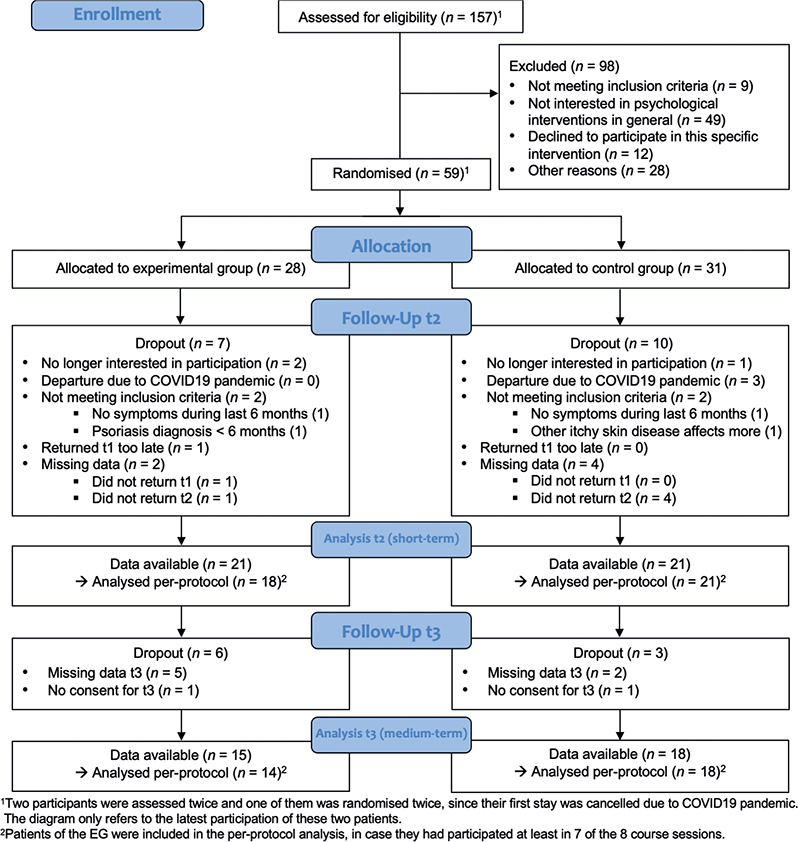

Of 59 patients allocated to EG or CG, data for 39 patients (14 male and 25 female) were included in the PP analysis of short-term effects, and 32 were included in the analysis of medium-term effects. The reductions in sample size occurred due to dropouts/missing data (Fig. 2 and Appendix S2). Mean age of the n = 39 patients was 49.8 years (SD = 10.5; range: 25 to 65). The SAPASI mean score for the whole sample (n = 39) was 6.2 (SD = 3.6; range: 1.0 to 16.1, n = 32), indicating a moderate severity of psoriasis (33). At baseline, participants of the EG and CG with complete data sets differed regarding the severity of psoriasis measured by the SAPASI [t(21) = 2.43, p = 0.024; n = 23]. No other group differences occurred at baseline (Table I).

| CG (n = 21) | EG (n = 18) | p-value | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 49.71 (10.23) | 49.83 (10.99) | 0.9723 |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (61.91) | 12 (66.67) | 0.7571 |

| Pre-existing mental disorders, n (%) | 3 (14.29) | 6 (33.33) | 0.2552 |

| Previous experience with mindfulness or meditation, n (%) | 5 (23.81) | 6 (33.33) | 0.5101 |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| Without possibility to go to college | 14 (66.67) | 10 (55.56) | 0.7382 |

| With possibility to go to college | 3 (14.29) | 4 (22.22) | |

| University | 4 (19.05) | 4 (22.22) | |

| Dermatological medication, n (%) | |||

| Topical therapy | 20 (95.24) | 13 (72.22) | 0.1452 |

| Systemic therapy | 4 (19.05) | 7 (38.89) | |

| Biologic therapy | 3 (14.29) | 0 (0) | |

| Dependent variables, mean (SD) | |||

| Mindfulness (CHIME) [1–6] | 3.94 (0.52) | 3.68 (0.51) | 0.1463 |

| Self-compassion (SCS-D) [1–5] | 3.17 (0.58) | 2.88 (0.68) | 0.1653 |

| Itch catastrophizing (ICQ) [0–4] | 1.57 (0.77) | 1.56 (1.24) | 0.9623 |

| Social anxiety (FNE) [1–5] | 2.54 (0.98) | 3.12 (1.05) | 0.0903 |

| Perceived stress (PSS-10) [0–4] | 1.89 (0.66) | 2.06 (0.68) | 0.4543 |

| Severity of psoriasis (SAPASI) [0–72] | 6.97 (3.87) | 4.99 (2.74) | 0.1243 |

| The reported means of the dependent variables refer to the baseline-measurement (t1; pre-intervention). EG: experimental group; CG: control group; SD: standard deviation; CHIME: Comprehensive Inventory of Mindfulness Experiences; SCS-D: German short form of the Self-Compassion Scale; ICQ: Itch-Cognition-Questionnaire; FNE: Fear of Negative Evaluation Questionnaire; PSS-10: Perceived Stress Scale 10; SAPASI: Self-Administered Psoriasis Area and Severity index. 1χ2 test; 2Fisher’s exact test; 3t-test for independent samples. | |||

Fig. 2. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Primary outcomes short-term analysis

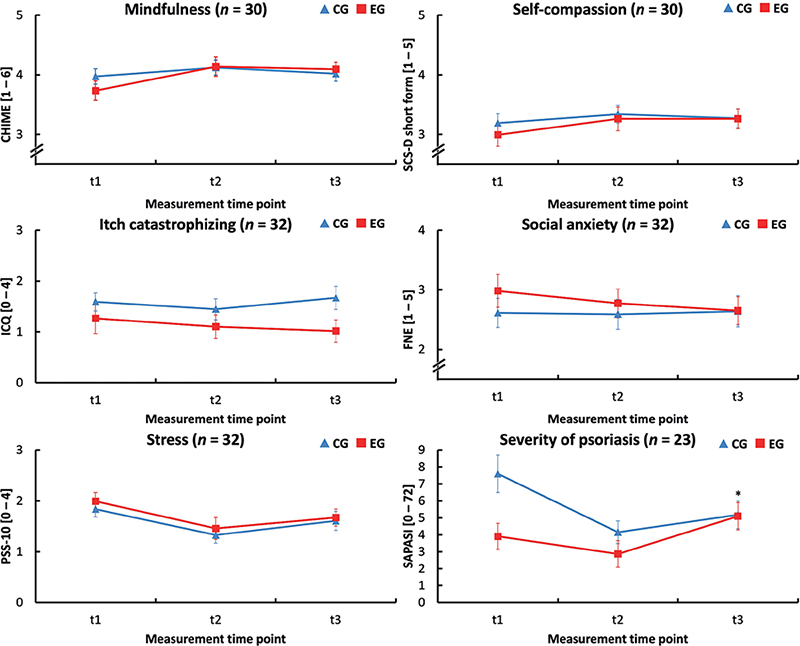

The short-term analyses (n = 39) revealed a significant interaction effect on mindfulness (CHIME) [F(1,35) = 7.46, p = 0.010, η2p = 0.18] and tendency to a significant effect on self-compassion (SCS-D) [F(1,36) = 3.03, p = 0.090, η2p = 0.08].

Moreover, in the short-term analysis significant time effects were found on mindfulness (CHIME) [F(1,35) = 25.57, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.42] and self-compassion (SCS-D) [F(1,36) = 10.28, p = 0.003, η2p = 0.22]. No group effects were found.

Primary outcomes: medium-term analysis

In the medium-term analyses (n = 32), a tendency to a significant interaction effect was found on mindfulness (CHIME) [F(2,56) = 2.47, p = 0.094, η2p = 0.08], but not on self-compassion (SCS-D) [F(2,56) = 0.59, p = 0.558, η2p = 0.02]. A time effect was found on mindfulness (CHIME) [F(2,56) = 7.23, p = 0.002, η2p= 0.21]. No group effects occurred.

Secondary outcomes

There was a significant interaction effect on the severity of psoriasis (SAPASI) [F(2, 42) = 4.15, p = 0.023, η2p = 0.17], indicating that the course of the severity of psoriasis from t1 to t3 differed between the EG and CG [F(1,21) = 7.02, p = 0.015, η2p = 0.25]. Furthermore, t-tests for dependent samples indicated a reduction in the severity of psoriasis (SAPASI) from t1 to t3 in the CG [t(13) = 2.36; p = 0.035], but not in the EG [t(8) = –2.19, p = 0.060; see Fig. 3]. No further interaction effects were found, either on itch catastrophizing (ICQ) [F(2, 60) = 0.87, p = 0.424, η2p = 0.03], or on social anxiety (FNE-K) [F(1.68, 50.29) = 0.87, p = 0.408, η2p = 0.03] or perceived stress (PSS-10) [F(2, 60) = 0.08, p = 0.927, η2p < 0.01]. Time effects were found for stress (PSS-10) [F(2,60) = 9.46, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.24] and the severity of psoriasis (SAPASI) [F(2,42) = 6.63, p = 0.003, η2p = 0.24]. No group effects were found.

Fig. 3. Effects of a brief mindfulness-based intervention on psychological variables and skin status. Illustrated are means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) in the experimental (EG) and control (CG) group at 3 time-points of measurement (t1 = pre-intervention; t2 = post-intervention; t3 = 3-month follow-up). EG: experimental group; CG: control group; CHIME: Comprehensive Inventory of Mindfulness Experiences; SCS-D: German short form of the Self-Compassion Scale; ICQ: Itch-Cognition-Questionnaire; FNE: Fear of Negative Evaluation Questionnaire; PSS-10: Perceived Stress Scale 10; SAPASI: Self-Administered Psoriasis Area and Severity index.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the effects of participation in a brief MBI in patients with psoriasis during a stay at a clinic for chronically ill patients. Primary outcome parameters were mindfulness and self-compassion, both assessed by validated questionnaires. Results of the short-term PP analysis indicated a significant large effect on self-reported mindfulness and a tendency to a significant moderate effect on self-reported self-compassion (38). Results of the medium-term PP analysis also yielded a tendency to a significant moderate effect on mindfulness (38). No other psychological variables were significantly affected by participation in the MBI. In addition to the reported short-term interaction effect in the PP analysis, the ITT analysis also showed a significant medium-term interaction effect for mindfulness in favour of the EG. This slightly different result (p = 0.094 vs p = 0.019) can be explained by the different sample size in the 2 analyses. As in the PP analysis no other interaction effects occurred in the ITT analysis.

Also, even though an improvement in skin status was observed in both groups at the end of the stay at the clinic, it is striking that, in contrast to other studies (18–21), the follow-up assessment revealed an improvement in skin status in the CG, but not in the EG. This finding could be interpreted as regression to the mean, as the baseline severity score was higher in the CG than in the EG. Moreover, although skin status in the EG worsened during the time at home, levels of itch catastrophizing, stress and social anxiety did not simultaneously increase in this group.

To better understand the results of this study, it is important to compare the kind of intervention and the setting used in this study with the interventions and settings used in other studies. In previous studies (18, 19, 22) extensive 8-week MBIs were applied to outpatients and the CG consisted of patients, who did not receive any kind of additional intervention. Thus, missing effects of the current study could have resulted from the shortness of the intervention and/or the type of CG, which received different therapies during a stay at a clinic in a relaxing atmosphere. This may have superimposed effects of the brief MBI. Further studies should therefore investigate the effects of a brief MBI in an outpatient setting and include a control group, which does not receive such comprehensive therapies.

Moreover, research on effect mechanisms of MBIs is needed. Increases in mindfulness and reductions in rumination have been suggested to mediate the effect of MBIs on somatic complaints (39). Regarding psoriasis, it is conceivable that mindfulness may help patients to decenter from dysfunctional thoughts (e.g. itch catastrophizing), which might subsequently lead to a change in illness-related coping-strategies (e.g. less scratching). When designing this study, it was planned to also use mediation models to explore potential effect mechanisms: We proposed that the effects could either be mediated by a physiological (mindfulness/ self-compassion↑ → stress↓ → severity of psoriasis↓) or an emotional-cognitive (mindfulness/self-compassion↑ → social anxiety/itch catastrophizing↓ → severity of psoriasis↓) pathway (23). Due to the lack of effects on most variables, these mediation analyses were not conducted. However, effect mechanisms should be addressed in future studies in case mindfulness has a direct effect on skin status. In addition, the investigation of the effects of mindfulness on disease-related behavioural measures (e.g. scratching) in a laboratory setting, as well as the use of physiological parameters, such as heart rate variability, could deepen the understanding of the underlying effect mechanisms.

Study limitations

The special context in which the MBI was delivered limited the generalizability. Furthermore, the large age range of the participants can be seen as limiting factor as it could have reduced the effects of the training. Homogenous age groups might improve the exchange in the group. This could be tested in future studies. It is also possible that the follow-up period was too short, as improvements through mindfulness practice may not be linear (40). Another limitation is the lack of an active control group as it has been used in a study that compared the effects of a brief MBI against a psychoeducational nutrition programme that was conducted in a similar setting and format, differing only in the aspect of mindfulness (41).

Moreover, data collection was impaired by the pandemic situation, so that the planned sample size of 60 patients could not be reached and dropout was higher than expected. The study thus remained underpowered.

Conclusion

This study investigated the effects of a brief MBI in patients with psoriasis. Large significant effects on self-reported mindfulness were found. However, effects on other psychological variables, measured by self-reports, did not reach significance. Thus, the effects of such a short intervention should be investigated further in a larger sample and different setting, possibly also using a group receiving a less comprehensive treatment than that used in the current study as TAU.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Jochen Kaiser from Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany, for his constructive feedback on a first draft of the manuscript during a workshop from the German Association of Medical Psychology (DGMP). Moreover, we thank Dr Julia Harfensteller for her support with the conductance of the intervention and Franziska Barschdorf for her assistance with data collection. We also thank all patients for their participation in the study.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Medicine at the Justus-Liebig-University Gießen (AZ 19/19) and the Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund before recruitment.

Patients provided written informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest: CS received speaker’s honoraria from Novartis and the university clinic of Münster during the last 3 years.

REFERENCES

- Augustin M, Reich K, Glaeske G, Schaefer I, Radtke M. Co-morbidity and age-related prevalence of psoriasis: analysis of health insurance data in Germany. Acta Derm Venereol 2010; 90: 147–151.

- Schut C, Dalgard F, Halvorsen J, Gieler U, Lien L, Aragones L, et al. Occurrence, chronicity and intensity of itch in a clinical consecutive sample of patients with skin diseases: a multi-centre study in 13 European Countries. Acta Derm Venereol 2019; 99: 146–151.

- Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, Gelfand JM. The risk of depression, anxiety and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146: 891–895.

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever You Go, There You are: mindfulness meditation for everyday life. London: Piatkus; 2004. 304 p.

- Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE, Fournier C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2015; 78: 519–528.

- Santorelli SF, Meleo-Meyer F, Koerbel L, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) Authorized Curriculum Guide. 2017. [cited 2019 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/center-for-mindfulness/documents/mbsr-curriculum-guide-2017.pdf

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JDT. Die Achtsamkeitsbasierte Kognitive Therapie der Depression: Ein neuer Ansatz zur Rückfallprävention. 2., erw. und überarb. Aufl. Tübingen: dgvt-Verlag; 2015. 494 p.

- Norton AR, Abbott MJ, Norberg MM, Hunt C. A systematic review of mindfulness and acceptance-based treatments for social anxiety disorder: mindfulness interventions for SAD. J Clin Psychol 2015; 71: 283–301.

- Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KMG. Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther 2016; 45: 5–31.

- Piet J, Hougaard E. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31: 1032–1040.

- Cavanagh K, Churchard A, O’Hanlon P, Mundy T, Votolato P, Jones F, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention in a non-clinical population: replication and extension. Mindfulness 2018; 9: 1191–1205.

- Vesa N, Liedberg L, Rönnlund M. Two-week web-based mindfulness training reduces stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in individuals with self-reported stress: a randomized control trial. Int J Neurorehabilitation 2016 [cited 2022 Mar 5]; 3. Available from: http://www.omicsgroup.org/journals/twoweek-webbased-mindfulness-training-reduces-stress-anxiety-and-depressive-symptoms-in-individuals-with-selfreported-stress-a-ran-2376-0281-1000209.php?aid=74146.

- Demarzo M, Montero-Marin J, Puebla-Guedea M, Navarro-Gil M, Herrera-Mercadal P, Moreno-González S, et al. Efficacy of 8- and 4-session mindfulness-based interventions in a non-clinical population: a controlled study. Front Psychol 2017 [cited 2023 Oct 25]; 8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01343

- Howarth A, Smith JG, Perkins-Porras L, Ussher M. Effects of brief mindfulness-based interventions on health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Mindfulness 2019; 10: 1957–1968.

- Schumer MC, Lindsay EK, Creswell JD. Brief mindfulness training for negative affectivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2018; 86: 569–583.

- Lüßmann K, Montgomery K, Thompson A, Gieler U, Zick C, Kupfer J, et al. Mindfulness as predictor of itch catastrophizing in patients with atopic dermatitis: results of a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Front Med 2021; 8: 627611.

- Montgomery K, Norman P, Messenger AG, Thompson AR. The importance of mindfulness in psychosocial distress and quality of life in dermatology patients. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175: 930–936.

- Fordham B, Griffiths CEM, Bundy C. A pilot study examining mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in psoriasis. Psychol Health Med 2015; 20: 121–127.

- Maddock A, Hevey D, D’Alton P, Kirby B. A Randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with psoriasis patients. Mindfulness 2019; 10: 2606–2619.

- Gaston L, Crombez JC, Joly J, Hodgins S, Dumont M. Efficacy of imagery and meditation techniques in treating psoriasis. Imagin Cogn Personal 1989; 8: 25–38.

- Kabat-Zinn J, Wheeler E, Light T, Skillings A, Scharf MJ, Cropley TG, et al. Influence of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention on rates of skin clearing in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing photo therapy (UVB) and photochemotherapy (PUVA). Psychosom Med 1998; 60: 625–632.

- D’Alton P, Kinsella L, Walsh O, Sweeney C, Timoney I, Lynch M, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness 2019; 10: 288–300.

- Stadtmüller L, Eckardt M, Zick C, Kupfer J, Schut C. Investigation of predictors of interest in a brief mindfulness-based intervention and its effects in patients with psoriasis at a rehabilitation clinic (SkinMind): an observational study and randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e033952.

- Stadtmüller LR, Eckardt MA, Zick C, Kupfer J, Schut C. Interest in a short psychological intervention in patients with psoriasis: a cross-sectional observational study at a German clinic. Front Med 2023; 10: 1074632.

- Lustyk MKB, Chawla N, Nolan RS, Marlatt GA. Mindfulness meditation research: issues of participant screening, safety procedures, and researcher training. Adv Mind Body Med 2009; 24: 20–30.

- Bergomi C, Tschacher W, Kupper Z. Konstruktion und erste Validierung eines Fragebogens zur umfassenden Erfassung von Achtsamkeit: Das Comprehensive Inventory of Mindfulness Experiences. Diagnostica 2014; 60: 111–125.

- Hupfeld J, Ruffieux N. Validierung einer deutschen Version der Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-D). Z Für Klin Psychol Psychother 2011; 40: 115–123.

- Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother 2011; 18: 250–255.

- Ehlers A, Stangier U, Dohn D, Gieler U. Kognitive Faktoren beim Juckreiz: Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens. Verhaltenstherapie. 1993; 3: 112–119.

- Reichenberger J, Schwarz M, König D, Wilhelm FH, Voderholzer U, Hillert A, et al. Angst vor negativer sozialer Bewertung: Übersetzung und Validierung der Furcht vor negativer Evaluation–Kurzskala (FNE-K). Diagnostica 2016; 62: 169–181.

- Klein EM, Brähler E, Dreier M, Reinecke L, Müller KW, Schmutzer G, et al. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale – psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry 2016; 16: 159.

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Reboussin DM, Rapp SR, Lyn Exum M, Clark AR, et al. The self-administered psoriasis area and severity index is valid and reliable. J Invest Dermatol 1996; 106: 183–186.

- Fleischer AB, Feldman SR, Rapp SR, Reboussin DM, Exum ML, Clark AR, et al. Disease severity measures in a population of psoriasis patients: the symptoms of psoriasis correlate with self-administered psoriasis area severity index scores. J Invest Dermatol 1996; 107: 26–29.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007; 39: 175–191.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY; 2020.

- Bennett DA. How can I deal with missing data in my study? Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25: 464–469.

- Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 5th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2017.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Saint Louis, USA: Elsevier Science & Technology; 1977. [cited 2022 May 2]. Available from: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unigiessen/detail.action?docID=1882849.

- Alsubaie M, Abbott R, Dunn B, Dickens C, Keil TF, Henley W, et al. Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological conditions: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2017; 55: 74–91.

- Galante J, Grabovac A, Wright M, Ingram DM, Van Dam NT, Sanguinetti JL, et al. A framework for the empirical investigation of mindfulness meditative development. Mindfulness 2023; 14: 1054–1067.

- Mrazek MD, Franklin MS, Phillips DT, Baird B, Schooler JW. Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychol Sci 2013; 24: 776–781.