QUIZ SECTION

Blue-brownish Nodule in the Umbilical Area: A Quiz

Piotr K. KRAJEWSKI and Jacek C. SZEPIETOWSKI*

Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Wroclaw Medical University, Chalubinskiego 1, PL-50-368 Wroclaw, Poland. *E-mail:jacek.szepietowski@umw.edu.pl

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv18368. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.18368.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Published: Sep 28, 2023

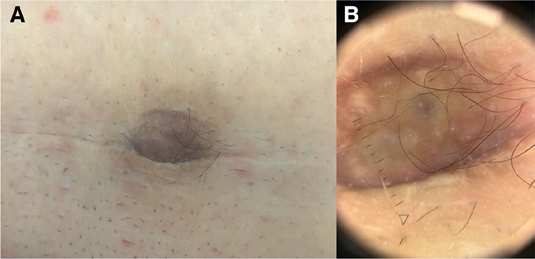

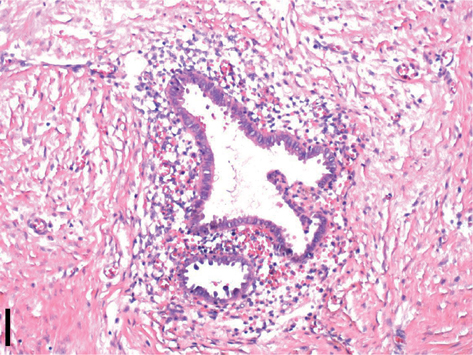

A 29-year-old woman with hidradenitis suppurativa was admitted to the Dermatology Unit for treatment of inflammatory skin lesions. She was a slightly obese Caucasian woman with a history of smoking. Physical examination revealed multiple inflammatory nodules, and abscesses, localized predominantly in the submammary area, and a blue-brownish nodule on the abdomen (Fig. 1a). The patient stated that the the umbilical nodule appeared in 2022 and was not associated with any subjective symptoms. Her medical history revealed that she had given birth via caesarean section in 2019, and 3 years later, a nodule had developed in the caesarean scar. She reported that the nodule was sometimes tender on palpation and that it might be associated with the menstrual cycle. The patient denied any bleeding from the lesion. Dermoscopy revealed a blue-brownish homogenous background with a centrally located hyperpigmented nest and discrete area of active bleeding (Fig. 1b). Ultrasound examination (BK Medical, 18 MhZ) revealed a well-demarcated, heterogeneous oval 2×3 cm nodule, localized primarily in the epidermis and subcutaneous tissue. Colour Doppler revealed limited vascularization, with tortuous vessels in its close surroundings. The lesion was subsequently excised with a good aesthetic outcome. Histological staining with haematoxylin and eosin revealed dilated glandular structures surrounded by endometrial glands, stroma, and signs of haemorrhage (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Blue-brownish nodule on the on a caesarean scar in the umbilical area. (A) Clinical photograph. (B) Dermoscopy of the nodule (magnification x10).

Fig. 2. Dilated glandular structures surrounded by endometrial glands, stroma, and signs of haemorrhage on haematoxylin and eosin staining. (Scale bar: 100 μm).

What is your diagnosis?

Differential diagnosis 1: Cutaneous endometriosis

Differential diagnosis 2: Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Differential diagnosis 3: Umbilical metastasis

Differential diagnosis 4: Keloid

See next page for answer.

ANSWERS TO QUIZ

Blue-brownish Nodule in the Umbilical Area: A Commentary

Diagnosis: Cutaneous endometriosis

Cutaneous endometriosis (CE) is a rare subtype of endometriosis, a chronic, inflammatory condition defined as the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside of the uterine cavity (1). The prevalence of endometriosis ranges between 5% and 15% in women of childbearing age, worldwide, while CE comprises only 0.5–1% of these (1, 2). The pathogenesis of CE is not fully elucidated; however, it may be divided into 2 subtypes: primary and secondary (3). The theory behind primary CE is based on the possible metaplasia of the peritoneal serosa cuff in which mesothelial cells of the peritoneum, due to chronic inflammation or hormonal factors, reshape into endometrial glands and/or stroma (3). Secondary CE may be attributed to iatrogenic metastasis, the implantation of endometrial cells during surgical procedures, and its further survival (1–3). This type has been linked to almost all gynaecological procedures, including laparoscopy, abortion, and episiotomy, but also to non-gynaecological surgeries, such as abdominal or inguinal hernia repairs (4). Secondary CE is much more common than primary CE and comprises almost 70% of all cases of CE (5). The typical clinical manifestation of CE is an oval or round, firm papule or nodule of red, brown, blue, or violet colour (2). The lesions are frequently associated with a characteristic history, of tenderness, itchiness, pain, bleeding, or serous discharge, related to the menstrual cycle (6). Although not prominent, cyclic tenderness was present in the current patient. The diagnosis is based on medical history, including gynaecological and surgical procedures, characteristic appearance, and histology. Moreover, dermoscopy and high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) may enable a correct diagnosis. Dermoscopic features of CE have been described and depend on the phase of the menstrual cycle. In the follicular phase, lesions may present reddish homogenous pigmentation or erythematous-bluish background, while in the follicular phase, light-brownish spots and areas of active bleeding may be visible (7). The picture of CE on HFUS is unspecific and has been described only for very HFUS (>70 MHz) (7). Nevertheless, the ultrasound images are usually similar to those seen in transvaginal ultrasound (US); i.e. hypoechoic or heterogeneous cystic lesions with limited vascularization (8). Histologically, CE is characterized by the appearance of endometrial glands consisting of tall columnar epithelium with basophilic cytoplasm, as well as high vascular stroma in the deep dermis (9). Moreover, due to menstrual bleeding, hemosiderin deposition, inflammation, and scarring may be reported (9). The differential diagnosis of red or brownish nodules includes keloid, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, melanomas, cancer metastases, and vascular lesions. One of the most characteristic features of CE distinguishing it from any other diagnosis is the cyclic nature of the appearance of subjective symptoms, including tenderness, itch, pain, or bleeding (2). CE should be treated in cooperation with the patient’s gynaecologist or endocrinologist and include surgical and hormonal treatment (2). Surgical excision with a wide margin is the treatment of choice and is associated with a very rare recurrence rate; however, subsequent hormonal therapy should be used in most advanced cases (2, 5, 6, 9). Hormonal treatment includes gonadotropic-releasing hormonal agonist, danazol, oral contraceptive, and the management of associated pain (1). On diagnosis of CE, the patient should be referred to a gynaecologist for consultation and further evaluation in order to exclude the presence of additional sites of endometriosis and further development of the disease. The prognosis of CE is rather favourable due to its benign nature; however, malignant transformations with clear cell carcinoma or endometrioid have been reported (10). The most common complication of CE is the recurrence of lesions after an incomplete excision (10).

CE is a rare clinical presentation of endometriosis appearing most frequently in caesarean section scars. The disease is characterized by formation of a nodule, red-brownish, firm, tender nodule with a cyclic appearance of subjective symptoms and, sometimes, bleeding associated with the menstrual cycle. The treatment of choice, as performed in the current patient, is surgical excision with a wide margin and subsequent histological examination.

REFERENCES

- Chapron C, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Santulli P. Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019; 15: 666–682.

- Sharma A, Apostol R. Cutaneous endometriosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL); 2023.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, Zarogoulidis P, Kouroutou P, Tsiamis N, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol 2013; 8: 194.

- Wolf Y, Haddad R, Werbin N, Skornick Y, Kaplan O. Endometriosis in abdominal scars: a diagnostic pitfall. Am Surg 1996; 62: 1042–1044.

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol 2017; 29: 621–625.

- Jaime TJ, Jaime TJ, Ormiga P, Leal F, Nogueira OM, Rodrigues N. Umbilical endometriosis: report of a case and its dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol 2013; 88: 121–124.

- Tognetti L, Cinotti E, Tonini G, Habougit C, Cambazard F, Rubegni P, et al. New findings in non-invasive imaging of cutaneous endometriosis: Dermoscopy, high-frequency ultrasound and reflectance confocal microscopy. Skin Res Technol 2018; 24: 309–312.

- Scioscia M, Virgilio BA, Lagana AS, Bernardini T, Fattizzi N, Neri M, et al. Differential diagnosis of endometriosis by ultrasound: a rising challenge. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020; 10.

- Kyamidis K, Lora V, Kanitakis J. Spontaneous cutaneous umbilical endometriosis: report of a new case with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Dermatol Online J 2011; 17: 5.

- Zhang P, Sun Y, Zhang C, Yang Y, Zhang L, Wang N, et al. Cesarean scar endometriosis: presentation of 198 cases and literature review. BMC Womens Health 2019; 19: 14.