SHORT COMMUNICATION

The Great Imitator’s Trick on Bones: Syphilitic Osteomyelitis

Yifan JIN1#, Wenxin ZHONG2#, Xia WANG2#, Changzheng HUANG1* and Yuan LU2*

1Department of Dermatology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 430022 Wuhan, Hubei, China and 2Department of Dermatology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University & Huazhong University of Science and Technology Union Shenzhen Hospital, 89 Taoyuan Road, Nanshan District, Shenzhen, 518052 Shenzhen, Guangdong, China. *E-mails: hcz0501@126.com; chfsums@163.com

#These authors contributed equally to this work.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2024; 104: adv18626. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v104.18626.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Submitted: Sep 2, 2023; Accepted: Jan 11, 2024; Published: Feb 12, 2024

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

INTRODUCTION

Syphilis, a common sexually transmitted disease caused by spirochete Treponema pallidum, is divided into 4 phases, primary, secondary, tertiary, and latent. Secondary syphilis has so many different manifestations that it is called “The Great Imitator”. In addition to various cutaneous lesions, syphilis can sabotage other systems, including the eyes, osteoarticular system, nervous system, and cardiovascular system, which exacerbates the patients’ suffering and substantially reduces their quality of life. Syphilitic osseous involvement is an uncommon complication of syphilis, which is atypical in secondary syphilis and has a high rate of misdiagnosis (1, 2). We report here a case of a man with syphilitic osteomyelitis of the fingers in the context of secondary syphilis.

CASE REPORT

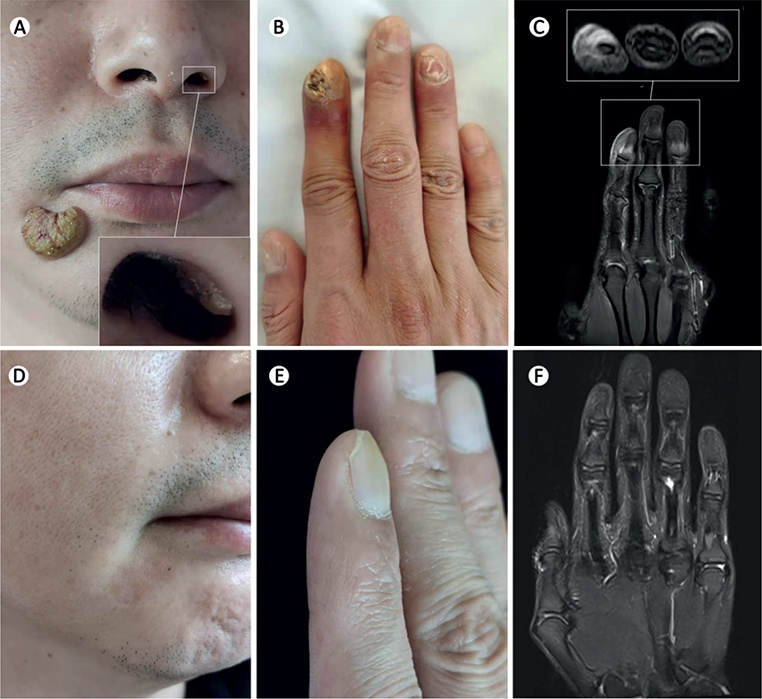

A 37-year-old man presented with a 1-month history of painful swelling in the fingers, and limited joint mobility. He had been treated with cefixime tablets (100 mg, twice a day) for 7 days for presumed arthritis with soft-tissue infections, which was ineffective. The patient reported several occasions of unprotected sexual intercourse with different partners over a period of almost 1 year. Physical examination revealed cauliflower-shaped variegated-brown nodules with moist surfaces in his right lower cheek and nasal cavity (Fig. 1A), and his hair was notably sparse, presenting as a “moth-eaten” alopecia pattern. Several non-tender, bean-sized, moderately-hard, mobilizable lymph nodes were distributed in his right jaw. In addition, multiple swollen knuckles were visible. The nails of his right middle 3 fingers were irregularly damaged, and longitudinal striations, increasing brittleness, deformation were detected (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Comparative observation of syphilitic osteomyelitis before and after therapy. (A) Photograph showing nodules on right lower cheek and nasal cavity (box). (B) Swollen knuckles and damage to right middle 3 fingernails. (C) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing different degrees of high signal in the distal phalanx of middle 3 fingers (especially the right index finger) in both transverse and vertical (box) views. (D, E, and F) Face, right middle 3 fingers, and T2-weighted MRI after therapy. The patient in this manuscript has given written informed consent to publication of the case details.

Laboratory studies showed a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay and an elevated rapid plasmin regain (RPR) titre of 1:640. With the specimens of the lesions on cheek and nails, a fungal microscopic examination and a fungal culture were performed, and the results were negative. In addition, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) detection for herpes simplex virus (HSV), human papilloma virus (HPV) 6, 11, 16, and 18 with the specimen from the cheek lesion, Chlamydia DNA assay and gonococcal culture with the urethral discharge, and assays of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B virus (HBV) antibody, hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody in sera were all normal. Biopsy specimens of the cheek nodule revealed superficial dermal infiltration of lymphocytes and plasmacytes, and a high level of Treponema pallidum were detected using immunohistochemistry staining. The T2-weighted image with fat-suppression shows the high intensity of the distal phalange of right index finger, high intensity of the surrounding swollen soft-tissues and discontinuities in local bone cortex, indicative of osteomyelitis (Fig. 1C).

A 3-week treatment with intramuscular benzathine penicillin G (BPG), given as a single injection of 2.4 million units weekly, was initiated. After 3 weeks, the nodus on the nasal cavity became invisible, while neither the cheek nodule nor finger swelling had improved satisfactorily. With a comprehensive consideration of the limited effects and at the patient’s strong request, a further dose of 2.4 million units BPG was prescribed. At the fifth week, the nodule on the patient’s cheek had disappeared with little remaining pigmentation and atrophy (Fig. 1D), and a significant amelioration of the redness and swelling was seen in his fingers. After 4 months, he underwent another RPR assay and the titre had reduced to 1:4. In addition, both the appearance and movements of his fingers had improved (Fig. 1E), and in the T2-weighted image with fat-suppression, the lesions in the distal phalanx and surrounding soft-tissue of the index finger as well as the abnormal signal intensity in the middle phalanx of the middle finger had improved significantly compared with the previous examination (Fig. 1F).

DISCUSSION

As a rare complication of syphilis, syphilitic osseous involvement mainly includes syphilitic periostitis, syphilitic osteitis, and syphilitic osteomyelitis, which mostly occurs in the skull and long bone of the limbs or fingers (3). It is generally observed in neonates born to infected mothers or in late-phase infections, but is quite atypical in secondary syphilis, which usually occurs 4–10 weeks after acquisition of primary syphilis (4). According to an earlier retrospective case series, only 0.15–0.23% of patients with early syphilis had bone lesions (5), hence even well-trained, experienced clinicians may misdiagnose it as other diseases.

To date, there are no specific guidelines for the diagnosis of syphilitic osseous involvement. Apart from the basal methods to anchor syphilis, imaging, especially high-resolution imaging techniques, play a crucial role in distinguishing definite osteal damage (3). However, imaging evidence is insufficient to obtain a final diagnosis, because it is not possible to conclude that the bone lesions are caused by syphilis. A bone biopsy may provide diagnostic evidence when Treponema pallidum is detected, while it sometimes reveals no clue, particularly in patients who simultaneously have AIDS (6, 7). In addition, despite some recent advances (8), in vitro cultivation of Treponema pallidum remains a challenge in pathological practice, which prevents bone biopsy from being performed routinely and becoming a gold standard.

Consequently, another current mainstream diagnostic technique, avoiding bone biopsy, exists to circumvent the above-mentioned dilemma. This is a reverse diagnostic strategy based on an improvement in osteal changes (both clinical manifestations and imaging features) after a formal anti-syphilitic treatment (7). With a primary diagnosis of secondary syphilis and findings of osteomyelitis, the current patient showed a significant reversal of bone changes and skin lesions after the injection of BPG, which confirmed the final diagnosis of osteomyelitis in secondary syphilis without the need for bone biopsy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by grants from the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 81972565).

REFERENCES

- Gaspari V, Mazza L, Pinto D, Raone B, Calogero P, Patrizi A. Syphilis as osteomyelitis of the fifth metatarsal of the left foot: the great imitator hits once again. Int J Infect Dis 2020; 96: 10–11.

- Lomholt G. Bone involvement in early syphilis. Arch Dermatol 1977; 113: 1300–1301.

- Petroulia V, Surial B, Verma RK, Hauser C, Hakim A. Calvarial osteomyelitis in secondary syphilis: evaluation by MRI and CT, including cinematic rendering. Heliyon 2020; 6: e03090.

- Dismukes WE, Delgado DG, Mallernee SV, Myers TC. Destructive bone disease in early syphilis. JAMA 1976; 236: 2646–2648.

- Mindel A, Tovey SJ, Timmins DJ, Williams P. Primary and secondary syphilis, 20 years’ experience. 2. Clinical features. Genitourin Med 1989; 65: 1–3.

- Chan MF, Moges F, Major D, Buss R, Biswas A. Calvarial lytic lesions in neurosyphilis with ocular involvement. IDCases 2022; 27: e01408.

- Kamegai K, Yokoyama S, Takakura S, Takayama Y, Shiiki S, Koyama H, et al. Syphilitic osteomyelitis in a patient with HIV and cognitive biases in clinical reasoning: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022; 101: e30733.

- Edmondson DG, Hu B, Norris SJ. Long-term in vitro culture of the syphilis spirochete Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum. mBio 2018; 9: e01153-18.