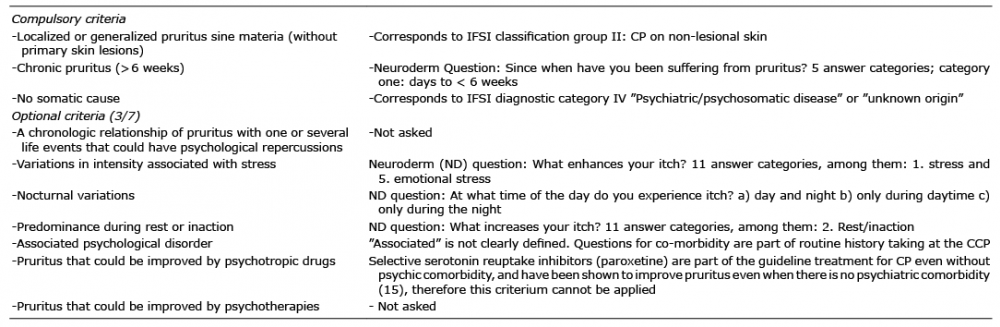

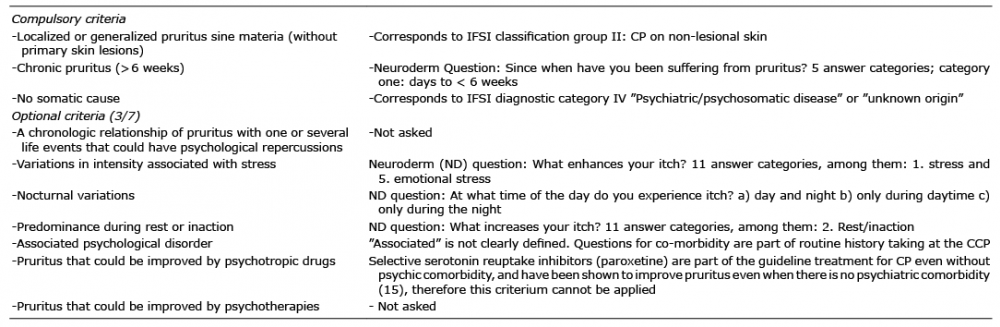

Table I. Criteria for psychogenic itch postulated by the French Psychodermatology Group that are part of the routine diagnostics at the Center for Chronic Pruritus (CCP) and the way they are collected

1Department of Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, 2Center for Chronic Pruritus, 3Institute of Medical Informatics and 5Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Münster, Münster, and 4inIT – Institute Industrial IT, Ostwestfalen-Lippe University of Applied Sciences, Lemgo, Germany

While psychological factors are relevant in many patients with chronic pruritus, not all patients can be offered psychologic, psychosomatic or psychiatric consultation. The aim of this exploratory study was to identify criteria suggestive of psychological factors relevant for the etiology of chronic pruritus and of somatoform pruritus. Routine data from the database of the Center for Chronic Pruritus of the University Hospital Münster were used, including the Neuroderm Questionnaire, Dermatology Life Quality Index and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Chronic pruritus patients (n = 3,391) without a psychiatric diagnosis in their medical history were compared to the 331 chronic pruritus patients with diagnoses of “psychological factors associated with etiology and course of chronic pruritus” (ICD-10:F54) or “somatoform pruritus” (F45.8) confirmed by an expert. The latter reported more pruritus triggers, especially “strain” and “emotional tension” and used more emotional adjectives to describe their pruritus. They reported more often scratching leading to excoriations, higher levels of pruritus, impairment of quality of life, anxiety and depression. These aspects suggest the presence of psychological factors in the etiology of chronic pruritus and somatoform pruritus. Prospective validation, however, needs to be carried out.

Key words: chronic pruritus; psychological factors; somatoform pruritus; psychogenic pruritus.

Accepted Feb 10, 2020; Epub ahead of print Feb 28, 2020

Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00075.

Corr: Gudrun Schneider, Department of Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Münster, Albert-Schweitzer Campus 1/A9, DE-48149 Münster, Germany. E-mail: Gudrun.Schneider@ukmuenster.de

Psychological aspects can cause or enhance chronic pruritus, but not all pruritus patients can be seen by a psychologist or psychiatrist. Patients with psychological factors in pruritus reported more pruritus triggers, especially “strain” and “emotional tension” and used more emotional adjectives to describe their pruritus. They reported more often scratching till excoriations, higher levels of pruritus, higher

impairment in life quality and higher levels of anxiety and depression. These aspects could help dermatologists to consider whether their patient should be presented to a psychologist or psychiatrist for further diagnoses or therapy.

Chronic pruritus (CP) is a frequent symptom of dermatologic, internal, neurologic or psychiatric diseases (1–5). The classification by the International Forum for the Study of Itch (IFSI) discriminates between: I. CP on lesional skin, II. CP on non-lesional skin, III. CP with chronic scratch lesions. As diagnostic categories, IFSI proposes the following: Pruritus induced by I: Dermatosis; II: Systemic disease; III: Neurologic disease; IV: Psychiatric / psychosomatic disease; V: Multifactorial origin; VI: Unknown origin (5, 6).

Diagnosis of “pruritus induced by psychiatric/psychosomatic disease” presents special challenges. When pruritus is not sufficiently explained by somatic diseases and can be better explained by psychosocial factors, it can be diagnosed as “Somatoform Pruritus” (F45.8). However, as much research is going on regarding somatic causes of pruritus and some causes may still be unknown, this diagnosis is hard to confirm in pruritus patients.

If there are underlying somatic causes and in addition, there are psychosocial factors that explain or influence CP and its management, the diagnosis “Psychological factors in diseases classified elsewhere” (F54) applies (5, 7, 8). According to the IFSI classification, this type of pruritus may be classified as “multifactorial”.

The diagnoses F45.8 and F54 must be differentiated from adjustment disorders (F43.2 in ICD-10). In these disorders psychological complaints arise due to a burdensome event, for example developing CP (7). However, in adjustment disorders the psychological symptoms follow the pruritus, and not vice versa. Of course, CP patients who have psychological influences on their pruritus may also develop adjustment disorder as a reaction to CP.

The presence of psychological factors in CP is usually diagnosed in patients that have been referred to a psychiatric or psychosomatic consultation after an expert interview of about one hour. Since not all CP patients can be referred within a reasonable time for such extensive diagnostic evaluation, availability of criteria suggestive of psychological factors underlying itch would help decide which patients should be referred for psychiatric/psychosomatic/psychological consultation. The main objective of this study was to make a first exploratory approach to identify such criteria.

In the scientific literature, the terms “functional or psychogenic itch/pruritus” are more commonly used than the diagnosis “somatoform pruritus” or “psychological factors in pruritus”. Diagnostic criteria for “functional” or “psychogenic” itch have been proposed by the French Psychodermatology Group (9, 10) (Table I). However, these criteria have been verified only in a small group of 31 CP patients without external validation in a second cohort or long-term follow-up studies (10). As these criteria are more widely used in the scientific and clinical community, we wanted to know if these criteria are helpful as possible criteria suggestive of psychological factors in itch (secondary objective).

Using the local CP database, we identified a subsample of CP patients in whom psychosomatic /psychiatric (PP) consultation had resulted in the diagnosis somatoform pruritus (ICD-10: F45.8) or psychological factors in pruritus (ICD-10: F54) and compared it with a subsample of CP patients with no current or known previous PP diagnosis. As this is an explorative study, we formulated no hypotheses in advance. However, we plan to validate the differences thus identified prospectively.

Table I. Criteria for psychogenic itch postulated by the French Psychodermatology Group that are part of the routine diagnostics at the Center for Chronic Pruritus (CCP) and the way they are collected

When patients present at the Center for Chronic Pruritus (CCP), they undergo extensive diagnostic evaluation and complete a set of questionnaires on mobile electronic devices such as a patient itch questionnaire (Münster NeuroDerm questionnaire) (11) and well-established and validated self-report scales assessing depression, anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale, HADS) (12) and dermatologic quality of life (Dermatological Life Quality Index, DLQI) (13). These data, together with the data on demographics, medical history and investigations recorded by the physician, are transferred to the electronic patient records and, if the patient agrees, into a patient database (11).

The local ethics committee approved the collection of patient data in the database and its use for research (2007-413-f-S). We used this database to identify patients who were referred for a PP consultation. Such referrals made by the treating dermatologists were not based on well-defined criteria. The differences between patients who were and those who were not referred for a PP consultation were examined in an earlier study (14). Those referred for this consultation were evaluated in a clinical interview lasting about 1 h by specialists trained in PP investigation in order to determine if they met the criteria for F45.8 or F54 of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (7). According to ICD-10, the diagnosis of F45.8 (“other somatoform disorder”) requires A) the exclusion of a somatic cause which explains the symptom and B) the symptom is related to burdensome psychosocial factors/events. If only B) applies, the diagnosis F54 (“psychological factors in diseases classified elsewhere”) is made. In adjustment disorder (F43) psychological complaints arise due to a burdensome event, for example developing CP (7). Therefore, in adjustment disorders the psychological symptoms follow the pruritus, and not vice versa. Adjustment disorder (F43) was diagnosed by asking the patient whether their psychological impairment (e.g. anxiety, depressed mood) developed after the CP started, as a reaction to CP. Psychologic influences on pruritus (F54 or F45) were diagnosed by asking the patients if at onset of CP there were any special life events and whether they experienced influences of life events, stress or emotions on CP.

The results of the PP consultation were extracted from the documentation of the Department of Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy. Patients with a diagnosis of F45.8 (somatoform pruritus) or F54 (psychological factors in pruritus) according to ICD-10 were compared to patients without a psychiatric/psychosomatic history (this item is part of the medical data recorded by the dermatologists), with regard to sociodemographic data, the Neuroderm items and DLQI and HADS scores of the first presentation at the center.

The exclusion criteria were age < 18 years and a history of psychiatric disease/diagnosis other than the diagnoses F45/F54 in the psychosomatic consultation.

Measures

The Neuroderm Questionnaire was developed by Ständer et al. (11) and comprises questions and descriptions deemed to be clinically relevant for chronic pruritus. It consists of a general part (which is reported here) and special modules. In the tables, only the Neuroderm items which show significant differences are reported; all the Neuroderm items and also the complete results are presented in detail in Appendix S1.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (12) was employed to assess the CP patients’ levels of depression and anxiety. The HADS consists of 14 items, which build an anxiety (HADS-A) and a depression subscale (HADS-D). It assesses the psychological symptoms of anxiety and depression but not their somatic manifestations (e.g. fatigue, lack of appetite). Therefore, it can be used to detect symptoms of depression and anxiety in the medically ill.

HRQoL was assessed according to Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI; 10 items, each with a score of 0–3 points; total score range 0–30 points) (13). A higher score signifies a higher QoL impairment.

Table I shows the criteria for psychogenic itch as postulated by the French Psychodermatology Group that are part of the routine diagnostics at the CCP and the way they are collected.

Statistics

As these are clinical data, unfortunately substantial amounts of data are missing concerning different variables. Therefore, it was not practicable to include only patients with complete data sets for all variables. As this is an explorative pilot study, we did not formulate hypotheses in advance. We included all cases which did not meet exclusion criteria, which resulted in different case numbers for each statistical comparison.

We employed χ2 tests for detection of distribution differences of nominal data and Student’s t-tests for detection of differences in means of continuous data. As this is an exploratory pilot study, we did not correct for multiple testing and regarded probability (p) levels of ≤ 0.05 as significant.

Where possible, we calculated effect sizes (Cohen’s d for t-tests and for χ2 tests with 1 degree of freedom) (16).

Between 2007 and 2016, data on 6,374 CP inpatients were entered into the database. As reported before (14, 17), 560 (8.8%) of them had been referred for a PP consultation. Fig. 1 gives an overview.

Of the 5,814 patients not referred for PP consultation, n = 2,556 self-reported a psychiatric or psychosomatic diagnosis in their medical history and were excluded from further analysis. Patients who had a medical history of other psychiatric/psychosomatic diagnoses in the PP referrals (n = 96) were also excluded from the analysis.

Those 3,391 patients without a psychiatric diagnosis in the PP referral (n = 133) or in their medical history (n = 3,258) (Non-Psych-CP) were compared to the 331 CP patients with the diagnoses “psychological factors associated with etiology and course of CP (F54 in ICD-10)” or with “somatization disorder” or “somatoform pruritus” (F 45.0 or F45.8 in ICD-10) (Psych-CP).

Fig. 1. The sample. CP: chronic pruritus.

Table II presents the basic sociodemographic characteristics and the IFSI classification of the two subgroups Psych-CP and Non-Psych-CP.

Psych-CP were significantly younger and more often female than Non-Psych-CP. They were more often single, divorced or widowed, while there was no significant difference in their occupational status. Regarding IFSI classification, Psych-CP more frequently belonged to the group with chronic scratch lesions (IFSI group III) and more seldom to the group with lesional skin (IFSI group I). Correspondingly, a smaller percentage of them fitted into the diagnostic category of “dermatosis” and a significantly higher percentage into that of “multifactorial origin”.

Table II. Comparison of chronic pruritus (CP) patients diagnosed with somatoform (“psychogenic”) pruritus (ICD-10: F45) or psychological factors associated with pruritus (ICD-10: F54) (Psych-CP) with patients with no psychiatric history/diagnosis (Non-Psych-CP), regarding sociodemographic and clinical variables and International Forum for the study of Itch (IFSI) classification

The significant differences between the two subgroups in the NeuroDerm Questionnaire are shown in Table III.

A higher percentage of Psych-CP reported CP duration longer than 10 years. More often, CP started on their neck, scalp or hands with a trend to localization on the scalp at presentation. They had higher pruritus intensity (average/worst/today) on their first presentation. Itch was reported as being localized deep inside, painful and experienced as pinpricks. They used more emotional adjectives while describing their CP, especially such descriptions as “cruel, makes me aggressive, agitating, terrible, oppresses me”. They reported a higher number of triggers increasing their itch, especially strain, emotional tension, physical effort and sweating. In reaction to their CP, Psych-CP reported more often to notch the skin with their nails and isolating themselves, and scratching until open wounds develop. In the psychometric scores, they scored higher for depression, anxiety and impaired life quality.

Table III. Comparison of the Neuroderm items between patients with somatoform (“psychogenic”) pruritus or psychological factors associated with pruritus (ICD-10: F45 orF54) with those without a psychiatric history; for complete item report, see Table SI.

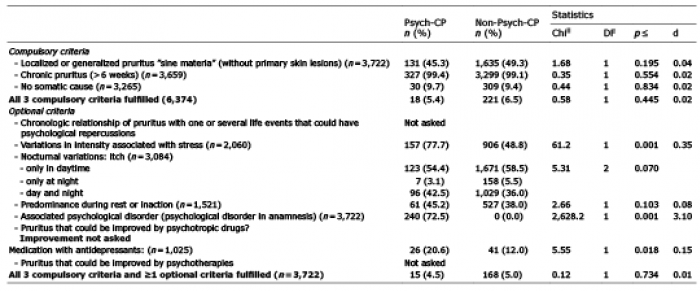

With regard to our second objective, a comparison of the Psych-CP and the Non-Psych-CP group the diagnostic criteria for psychogenic itch (9) is displayed in Table IV. There were no significant differences in the distribution of the 3 compulsory criteria, but only a small percentage of Psych-CP patients fulfilled all 3 compulsory criteria. This was mainly due to the criterium “no somatic cause”, which applied to only 9–10% of our CP patients. Regarding the optional criteria, the Psych-CP reported significantly more frequently variations in intensity associated with stress, and more often took antidepressants. Contrary to the formulated criterium which postulates nocturnal variations in “psychogenic itch”, they showed a trend to less nocturnal variations. As we compared only patients without a present or past psychiatric history, the optional criterium “associated psychological disorder” was absent in all CP patients of the latter subgroup. In both subgroups, only a small percentage of the patients fulfilled all three compulsory criteria and even fewer all compulsory criteria and at least one optional criterium.

Table IV. Comparison of chronic pruritus (CP) patients diagnosed with somatoform (“psychogenic”) pruritus or psychological factors associated with pruritus (Psych-CP; n = 331) (ICD-10: F45 or F54) and those without a psychiatric history (Non-Psych-CP ; n =3,391) group regarding fulfillment of the diagnostic criteria for psychogenic itch (9)

Using data from a large sample of adult CP patients, we made a retrospective comparison of clinical and self-reported features between patients who fulfilled the criteria for the ICD diagnoses “somatoform pruritus” or “psychological factors in the etiology or course of CP” (Psych-CP) with patients with no history of a psychiatric diagnosis.

Interestingly, 2,556 CP patients (40.1% of all CP patients) reported previous or current psychiatric comorbidities, which corresponds to a higher lifetime prevalence than reported for the German general population in the Federal Health Survey (25.3% for men and 37% for women) (18). This could be due to the high burden of CP or to the fact that pruritus is frequent in psychiatric patients (19). The aim of the study was to identify features suggestive of these diagnoses and thus help dermatologists decide which patients should be considered for a specialist PP consultation.

We further tried to apply the criteria regarding “psychogenic or functional” itch formulated by the French Dermatology Group (9, 10).

We found some differences between the subsamples. Psych-CP were more often female, single and belonged to the IFSI-group III with chronic scratch lesions. The association between psychological factors in CP, female sex and chronic scratch lesions is in line with previous findings. In the general population, somatoform disorders have a higher prevalence among women than among men (15% vs. 7%) (18). Among CP patients, higher psychiatric comorbidity has been reported for female CP patients than for male CP patients (20, 21). Ständer et al. (22) reported that women had more psychosomatic diseases underlying CP and that they significantly more often showed a worsening of CP by emotional and psychosomatic factors and also that women significantly more often showed chronic scratch lesions and prurigo nodularis, in contrast to men, who significantly more frequently had CP on non-inflamed skin. A high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic prurigo (which belong to IFSI group 3) has been reported before, but in these patients, mainly anxiety and depression were investigated, and not specifically somatoform pruritus or psychological factors in the etiology of pruritus (8, 23–26). Akarsu et al. (27) reported psychological factors associated with CP in 41.3% of a female sample (n = 80) of CP patients with prurigo nodularis.

Psych-CP self-reported more pruritus triggers, especially “strain” and “emotional tension” and used more emotional adjectives to describe their pruritus. Beginning of the pruritus was more often on scalp, neck or hands and they reported more often scratching till their skin showed excoriations. They also had higher intensities of pruritus at their first presentation at the CCP. In self-report scales, they reported more impairment in life quality, anxiety and depression. Of course, no single feature of these can lead to the diagnosis of F45 or F54, as no feature occurs exclusively in the Psych-CP group.

Also the fact that they reported more anxiety and depression in the self-report scales does not mean that these aspects are necessarily triggering CP. Impairment of life quality, depression and anxiety are often sequelae of CP, suggesting the diagnosis of adjustment disorder (F43) as a reaction to CP. This cannot be differentiated by the questionnaires, as these are cross-sectional. The differentiation was made in the diagnostic interview, in which the CP patients were asked whether their psychological impairment (e.g. anxiety, depressed mood) developed after the CP started, as a reaction to CP. Psychologic influences on pruritus (F54 or F45) were diagnosed by asking the patients if at onset of CP there were any special life events and whether they experienced influences of life events, stress or emotions on CP. This differentiation relies on the patient`s memory and anamnestic statements and might be faulty. Patients with psychologic influences on CP may also develop adjustment disorder, in the sense of a co-morbidity between F54/F45 and F43.2.

In a former paper we reported that (44.7%) of CP patients which were referred to our specialist consultation and diagnosed with a psychiatric morbidity fulfilled criteria for more than one psychiatric/psychosomatic diagnosis (14). The main factors associated with a specialist PP referral were female sex, number of comorbidities, chronic scratch lesions and psychological burden (14). Of these, female sex, chronic scratch lesions and psychological burden were also associated with psychologic influences on CP in our present analysis. This could be an indicator that dermatologists already associate these factors with a need for a specialist PP referral.

The 3 compulsory diagnostic criteria for psychogenic of the French Dermatology Group were fulfilled only by a very small number of patients. This was mainly due to the criterium “no somatic cause” which necessitates extensive work-up and follow-up of the patient and is thus hard to confirm in CP. From the optional criteria, the clearest applicability could be found for “variations in intensity associated with stress” while “nocturnal variations” showed only a trend towards significance.

We conclude that these criteria, as they are formulated now, may be helpful in diagnosing somatoform itch (F45.8), which, however seems to occur quite rarely. The compulsory criteria are, however, not helpful for the diagnosis of psychological factors in itch (F54), as these may occur in addition to an organic cause of pruritus and also in patients with primary skin lesions. However, some of the optional criteria might be helpful for the diagnosis of psychological factors in itch (F54), namely variations in CP intensity associated with stress and a chronologic relationship of pruritus with life events that could have psychological repercussions (9).

Limitations

However, there are a number of limitations to our approach. As this is a clinical study, heterogeneous numbers of patients filled in the Neuroderm items and other questionnaires. It would be preferable if all CP patients responded to all items. Statistically, the numbers between the subgroups were very different and we did not correct for multiple testing. Most effect sizes were in the small to medium range. The subgroup with no history of psychiatric disease did not undergo specialized PP diagnostics. Accordingly, it cannot be ruled out that a certain percentage of them also fulfilled the F45/F54 diagnostic criteria. However, this would probably only diminish the differences between the subgroups, not enhance them; therefore, the differences we found can be regarded as relevant, but there may be others which we did not detect. Also, this is an exploratory retrospective study. The differences we found have to be reproduced and validated prospectively. Not all of the criteria for psychogenic itch of the French Dermatology Group are part of the routine diagnostics at the CCP.

Conclusions

From our data, we can still draw some preliminary conclusions. The criterium “no organic cause” seems to be hard to confirm in CP, pruritus of multifactorial origin is much more frequent. There is a clinically relevant number of patients among those with CP of multifactorial origin in whom pruritus is influenced by psychological factors; these also could be relevant for treatment response and should be taken into consideration in their treatment (8, 17). In a previous study, our group found predominant psychogenically induced pruritus, in the sense of dissociative or somatoform disorder (F44, F45), in only 5.5% of the sample (6 out of 109 patients). The most frequent diagnosis was “psychological or behavioral factors associated with disorders or diseases classified elsewhere” (F54), in the sense of a psychological component in the etiology and course of CP (8). This finding has been replicated by the data presented here. Therefore, we conclude that the diagnosis “psychological factors associated with etiology and course of CP (F54 in ICD-10)” is clinically more relevant than that of “somatoform pruritus” (F45.8).

Indicators for Psych-CP could be relevant in chronic scratch lesions, scratching until occurrence of excoriations, reporting of the triggers stress, strain, emotional tension and using emotional adjectives when describing their CP. Some of these might be useful in dermatological practice, e.g. the question whether CP was increased by stress or emotional tension could be easily integrated into the dermatological case history. Also higher levels of pruritus, impairment in life quality, anxiety and depression (which could be recorded by questionnaires) might be suggestive of the diagnosis of “psychological factors associated with etiology and course of CP (F54 in ICD-10)”. In our next study, we plan to validate these criteria prospectively.