Mass vaccination programmes are crucial to counter the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. Provision of a 3rd vaccine as a booster dose commenced recently worldwide, with the aim of enhancing immunity and effectiveness of the vaccination programme over time in the context of the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Omicron (1). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for COVID-19 vaccines were performed in record time, documenting good safety and immunogenicity profiles (2). Nevertheless, during RCTs and post-marketing phases some immediate (anaphylaxis, urticaria-angioedema syndrome) and, rarely, delayed (maculo-papular eruptions) hypersensitivity reactions were observed (2). Strictly considering mucocutaneous reactions, local injection site (the so-called “COVID arm”) and generalized reactions, (urticaria/angioedema, maculopapular, morbilliform and papular-vesicular rashes, pityriasis rosea-like, reactivation of varicella zoster and herpes simplex virus, erythema nodosum, lymphomatoid eruption, pseudo-chilblain relapsing, and lichen planus) were described (3). Severe reactions (acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis) have been rarely reported (2, 3). Considering this wide spectrum of skin manifestations, the role of dermatologists is crucial in defining correct diagnosis and management (3).

The causative agents and pathomechanism of mucocutaneous adverse reactions after the first-dose COVID-19 vaccine are difficult to establish; the excipients contained in the vaccine could potentially play a role as sensitizers. In view of this, an accurate allergy work-up is recommended when a hypersensitivity reaction to excipients is suspected (4).

Among the COVID-19 vaccines used in Italy, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-2000 is contained in BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna), tromethamine in mRNA-1273 (Moderna), and polysorbate-80 in AZD1222 (AstraZeneca) and Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen) (2). All of the above excipients are well-known sensitizers, especially responsible for immediate reactions (5).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the sensitizing role of excipients in patients with mucocutaneous adverse reactions after the first-dose COVID-19 vaccine. These patients were referred to us to clarify this issue in order to continue, stop or modify the COVID-19 vaccine programme.

METHODS AND RESULTS

A total of 19 patients (16 females, 3 males; mean age 47.0 years) referred to us for mucocutaneous reactions to a first-dose COVID-19 vaccine. These patients were referred to us by their vaccination centre with the specific request to clarify the possible sensitizing role of excipients contained in the administered vaccine and to obtain a certification of avoidance or permission for the 2nd dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Without this certification patients would not have consented to be given the 2nd dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. In view of this, we designed a skin test work-up with pure COVID-19 vaccine excipients based on patch test with PEG-2000 and polysorbate-80 (5% in petrolatum) and tromethamine (1% in saline solution), applied for 48 h and with readings after 48 and 96 h; skin-prick test (SPT) with PEG-2000 and polysorbate-80 (0.01–0.1–1% in ethanol) and tromethamine (0.1% in ethanol); intradermal test (IDT) with PEG-2000, polysorbate-80, and tromethamine (0.01% in saline solution), with readings after 20 min and 24 h (6). The allergens were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy) and prepared by our hospital pharmacy (7). We did not use vaccines “as is” to perform skin testing, since in patients who received at least a first-dose vaccine the intradermal test always resulted false-positive, due to an immunological and not an allergic pathomechanism (8). The same allergological work-up was also performed in 2 control groups: 15 volunteers who had received and well tolerated the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and 15 volunteers who did not start vaccination. Patients and controls with no reactions to the first vaccine dose underwent skin tests 3 weeks after receiving the first dose.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Umbria, Italy (n. 21051/21) and patients provided written informed consent for publication of their data.

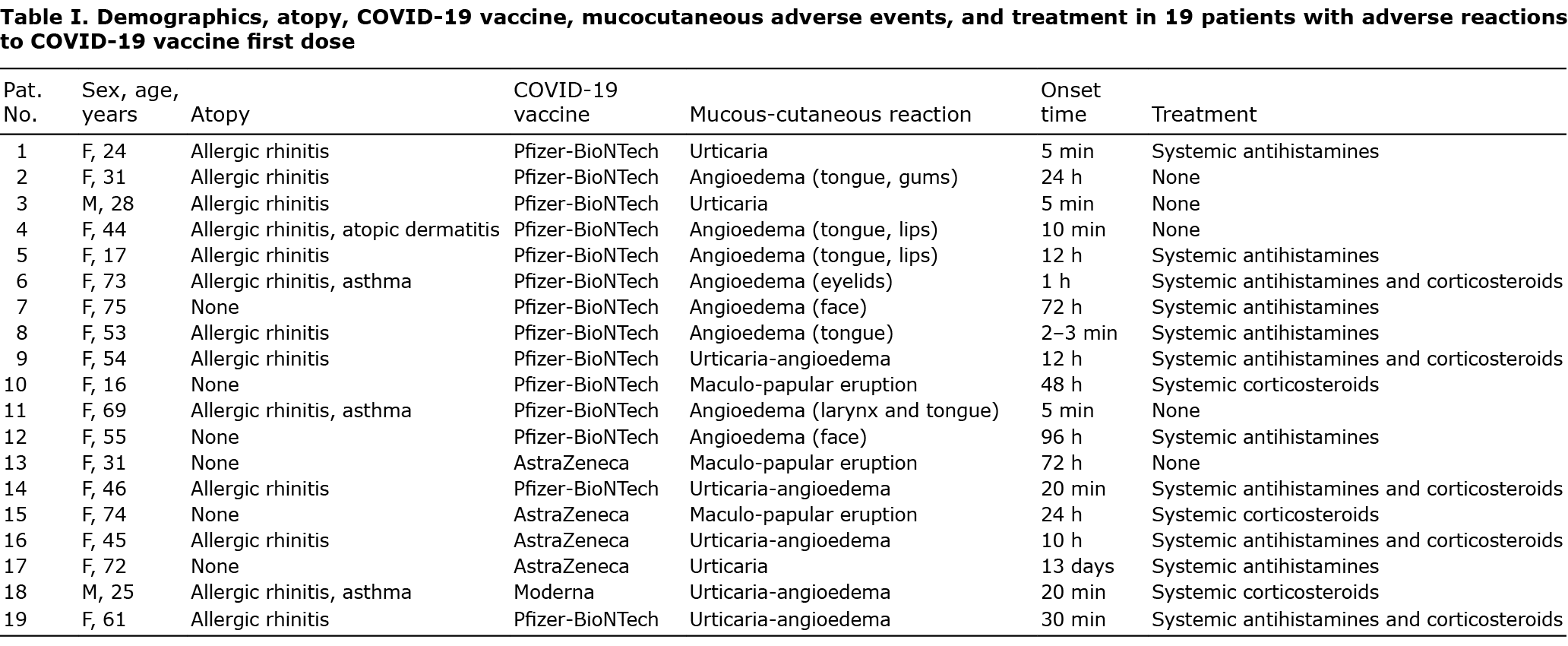

Demographics, atopy, COVID-19 vaccine administered, mucocutaneous reactions and their onset time, and treatment were assessed and summarized (Table I). Immediate reactions were observed in 16 patients (urticaria in 3, angioedema in 8, urticaria-angioedema in 5), while delayed reactions (maculopapular eruption) in 3. None of the current 19 patients developed positive reactions to patch test, skin-prick test and intradermal test with the pure vaccine excipients, as well as the 30 volunteers belonging to the 2 control groups. All patients and controls reported transient local burning after tromethamine intradermal test. No irritant reactions were observed in the whole study group.

These negative results enabled us to advise patients to receive the 2nd-dose COVID-19 vaccine, which was well tolerated by all subjects without any recurrence of the mucocutaneous reaction as reported after the first-dose vaccine.

DISCUSSION

During recent months, the role of skin tests with excipients in the diagnosis of mucocutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines has been debated. This issue derives from the knowledge that PEGs, polysorbates, and tromethamine contained in drugs can cause allergic reactions and rarely complement activation-related pseudo-allergy (2).

In our selected group of patients we documented a higher prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine immediate reactions (84.2%) than delayed ones. The negative skin test results in all patients seem to exclude hypersensitivity to excipients. It should be noted that, for these patients, we received a specific request to advise avoidance of, or permission to receive, further vaccine doses, based on confirmed or excluded hypersensitivity to excipients. To ensure high specificity in the diagnostic procedure it is advisable to perform skin testing with pure excipients (9).

In previous studies skin tests were performed, not using pure excipients, but drugs “as is” containing the same or similar excipients, indicating a limited role for excipient skin testing (10, 11). Recent consensus guidance on allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines recommended further coordinated research studies to address vaccine and vaccine excipient testing diagnostic accuracy (2). In fact, performing SPT and IDT with drugs containing polysorbate-80 in patients with immediate and delayed reactions to COVID-19 vaccines, the majority (85.7%) of positive reactions were observed using the drug, which caused irritative reactions in 52.0% of control subjects (10). Moreover, 70.0% of positive patients did not relapse when they received the 2nd vaccine dose, suggesting that these reactions could be prevented using pure excipients for skin testing. Consistent with this, pure polysorbate-80 used to perform SPT and IDT in patients allergic to PEGs demonstrated the tolerability of COVID-19 vaccines containing polysorbate-80 and highlighted good sensitivity and good negative predictive value of skin tests with this pure excipient (12).

Another issue influencing the hypothesized limited role of excipient skin testing is that, in some studies, drugs containing different PEGs, such as PEG-3550 (10, 11), PEG-4000 (12) and PEG-6000 (12), compared with PEG-2000 were used. In our case series we tested PEG-2000 contained in vaccines, and no other PEGs with different molecular weight, since the latter could influence the immunoreactivity of this excipient. PEGs with higher molecular weight may require a lower test concentration when investigating suspected immediate-type PEG hypersensitivity (13).

In conclusion, the current study data for 19 patients with adverse reactions after COVID-19 first-dose vaccine emphasize the good tolerability and high negative predictive value of skin tests with pure excipients. These skin tests had negative results in all of the 19 current study patients, and all 19 patients subsequently tolerated the COVID-19 2nd-dose vaccine well. These preliminary results need to be verified in a larger study population. In the study patients the pathomechanism of the first-dose COVID-19 vaccine reactions remains unknown, but, in some cases, a transient immunological non-allergic reaction cannot be excluded (14). The role of dermatologists in predicting COVID-19 vaccine mucocutaneous reactions is crucial, not only for their maagement, but also to help patients avoid COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the context of the ongoing global pandemic. Without final certification documenting the negativity of tests carried out with the pure excipients of the COVID-19 vaccines, none of the current 19 patients would have consented to receive the 2nd dose of the vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Pajon R, Doria-Rose NA, Shen X, Schmidt SD, O’Dell S, McDanal C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant neutralization after mRNA-1273 booster vaccination. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 1088–1091.

- Greenhawt M, Abrams EM, Shaker M, Chu DK, Khan D, Akin C, et al. The risk of allergic reaction to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and recommended evaluation and management: a systematic review, meta-analysis, GRADE assessment, and international consensus approach. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 3546–3567.

- Català A, Muñoz-Santos C, Galván-Casas C, Roncero Riesco M, Revilla Nebreda D, Solá-Truyols A, et al. Cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a cross-sectional Spanish nationwide study of 405 cases. Br J Dermatol 2022; 186: 142–152.

- Sokolowska M, Eiwegger T, Ollert M, Torres MJ, Barber D, Del Giacco S, et al. EAACI statement on the diagnosis, management and prevention of severe allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines. Allergy 2021; 76: 1629–1639.

- Caballero ML, Quirce S. Excipients as potential agents of anaphylaxis in vaccines: analyzing the formulations of currently authorized COVID-19 vaccines. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2021; 31: 92–93.

- Stingeni L, Bianchi L, Tramontana M, Pigatto PD, Patruno C, Corazza M, et al. Skin tests in the diagnosis of adverse drug reactions. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2020; 155: 602–621.

- Barbaud A, Gonçalo M, Bruynzeel D, Bircher A; European Society of Contact Dermatitis. Guidelines for performing skin tests with drugs in the investigation of cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Contact Dermatitis 2001; 45: 321–328.

- Bianchi L, Biondi F, Hansel K, Murgia N, Tramontana M, Stingeni L. Skin tests in urticaria/angioedema and flushing to Pfizer-BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: Limits of intradermal testing. Allergy 2021; 76: 2605–2607.

- Mortz CG, Kjaer HF, Rasmussen TH, Rasmussen TH, Garvey LH, Bindslev-Jensen C. Allergy to polyethylene glycol and polysorbates in a patient cohort: diagnostic work-up and decision points for vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Transl Allergy 2022; 12: e12111.

- Wolfson AR, Robinson LB, Li L, McMahon AE, Cogan AS, Fu X, et al. First-dose mRNA COVID-19 vaccine allergic reactions: limited role for excipient skin testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 3308–3320.

- Greenhawt M, Shaker M, Golden DBK. PEG/polysorbate skin testing has no utility in the assessment of suspected allergic reactions to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 3321–3322.

- Ieven T, Van Weyenbergh T, Vandebotermet M, Devolder D, Breynaert C, Schrijvers R. Tolerability of polysorbate 80 containing COVID-19 vaccines in confirmed PEG allergic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 4470–4472.e1.

- Wenande E, Garvey LH. Immediate-type hypersensitivity to polyethylene glycols: a review. Clin Exp Allergy 2016; 46: 907–922.

- Gambichler T, Boms S, Susok L, Dickel H, Finis C, Rached NA, et al. Cutaneous findings following COVID-19 vaccination: review of world literature and own experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 172–180.