Type D personality is characterized by social inhibition and negative affectivity. Poorer outcomes and worse quality of life have been linked to type D personality in patients with a variety of non-dermatological diseases. Despite increasing evidence of the importance of type D personality in skin diseases, there are no reviews on this subject. The aim of this review is to summarize the current evidence regarding type D personality and skin diseases. A systematic search was performed using Medline and Web of Science databases from inception to 11 October 2022. Studies addressing the presence of type D personality, its associated factors, its impact on the outcomes of the disease or the quality of life of the patients were included in the systematic review. A total of 20 studies, including 3,124 participants, met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. Acne, hidradenitis suppurativa, psoriasis, melanoma, atopic dermatitis, chronic spontaneous urticaria and pruritic disorders were the main diseases assessed. Type D personality was more frequent among patients with skin diseases than among controls. Type D personality was found to be associated with poorer quality of life and higher rates of psychological comorbidities in patients with skin diseases. In conclusion, type D personality appears to be a marker of patients with increased risk of poorer quality of life and higher rates of psychological comorbidities. Screening for type D personality in specialized dermatology units might be beneficial to identify patients who are more psychologically vulnerable to the consequences of chronic skin diseases.

Key words: skin diseases; quality of life; anxiety; depression; type D personality.

Accepted Dec 9, 2022; Published Jan 10, 2023

Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv00846.

DOI: 10.2340/actadv.v103.2741

Corr: Alejandro Molina-Leyva, Dermatology Department, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Avenida de las Fuerzas Armadas 2, ES-18014 Granada, Spain. E-mail: alejandromolinaleyva@gmail.com

SIGNIFICANCE

Type D personality is characteristic of people with social inhibition and negative affectivity. There is increasing evidence that having this personality type may be associated with a worse outcome in patients with skin diseases. A review of all the published articles regarding type D personality in people with skin diseases found that patients with skin diseases are more likely to exhibit this type of personality, and they have poorer quality of life and higher rates of psychological comorbidities. Therefore, screening for type D personality in dermatology consultations might be beneficial in order to identify patients who are more psychologically vulnerable.

INTRODUCTION

The personality is a stable psychological construct composed of inherent and acquired thoughts and beliefs, and represents the way each person interacts with the inner and outer environment (1). Different personality types have been described (2), which can have an impact on the social and work interactions of people who exhibit them (3). On the other hand, some personality types have been linked to differences in how patients cope with disease and in how the disease affects them (4).

In this regard, type D personality represents a stable personality trait, which is characterized by a combination of social inhibition (SI) and negative affectivity (NA) (i.e. patients with elevated scores in both SI and NA traits) (5). SI can be defined as a tendency to withdrawal from new people and avoidance of social situations, whereas NA is defined as a tendency to experience negative emotions (5).

There is increasing evidence regarding the negative impact of this type of personality in a variety of physical, mental and emotional aspects of both healthy and diseased individuals (6). For example, some studies show a link between type D personality and worse outcomes in cardiovascular disorders, including higher burden of coronary calcification (7) or higher probability of having myocardial infarction (8), although these associations remain controversial (9).

It is currently clear that type D personality is associated with a worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with cardiovascular disease (10, 11). Similar results have been found for a wide range of diseases, such as cancer (12, 13), periodontal disease (14), temporo-mandibular disease (15), inflammatory bowel disease (16), fibromyalgia (17), diabetes mellitus (18), and skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis (19) or psoriasis (20). These results suggest that the presence of type D personality could lead to dysfunctional coping strategies in patients, which would be responsible for worse quality of life, higher rates of psychological comorbidities and, in some cases, potentially worse disease control.

Furthermore, there are currently no reviews assessing the impact of type D personality on patients with skin diseases. Since type D personality may be linked to worse disease outcomes and poorer quality of life in patients, the development of a structured summary of the available evidence on type D personality and skin diseases would be of interest as a starting point for future studies.

The aims of this systematic review are to describe the available evidence regarding the frequency of type D personality and to assess its relationship with worse quality-of-life, mood status disturbances and disease outcomes in patients with skin diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

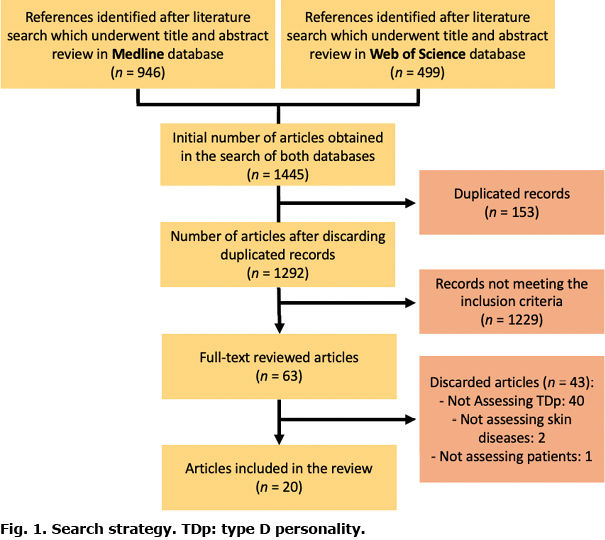

A literature search was performed using Medline and Web of Science databases from inception up to 11 October 2022. The following search terms were used: (((type D personality) OR social inhibition) OR negative affectivity) AND (skin disease OR cutaneous disease OR skin OR dermatology OR psoriasis OR hidradenitis OR acne OR urticaria OR skin cancer OR melanoma OR alopecia OR dermatitis OR eczema OR rosacea).

The PRISMA 2020 checklist guidelines for systematic reviews were followed in performing this systematic review (Table SI).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search was limited to: (i) studies on patients with skin diseases; (ii) studies addressing the presence of type D personality, its associated factors or its impact on the outcomes of the disease or the quality of life of patients; (iii) any type of epidemiological studies (clinical trials, cohort studies, case-control studies and cross-sectional studies); (iv) articles written in English or Spanish. Guidelines, protocols, and conference abstracts were excluded.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts obtained in the first search were reviewed by 2 different researchers (MSD and AML) to assess relevant studies. The full texts of all articles that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed, and their bibliographic references were checked for additional sources. Uncertainties about inclusion or exclusion of articles were subjected to discussion with a third investigator (SAS) until a consensus was reached. The articles considered relevant were included in the analysis.

Research questions and variables assessed

The research questions were as follows:

- Is type D personality associated with worse severity of skin diseases?

- Is type D personality associated with poorer quality of life in skin diseases?

- Is type D personality associated with higher rates of psychological comorbidities?

To answer these questions, variables assessed were the different skin diseases evaluated and their severity scores, the potential impact of type D personality on the severity of the disease, the potential impact of type D personality on the quality of life of patients, the potential impact of type D personality on psychological comorbidities, and socio-demographic characteristics of the patients included in the studies. Moreover, the method the authors follow to analyse type D personality was included (dichotomous vs numerical scores for SI and NA).

Risk of bias and level of evidence

The risk of bias for the studies included in the review was assessed following the “Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies” of the National Institutes of Health (Table SII). The level of evidence was recorded according to the Center for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). Levels of evidence were recorded as follows: r1a: Evidence obtained of systematic reviews or meta-analysis of randomized control trials; 1b: Evidence obtained from individual randomized control trials; 2a: Evidence obtained from systematic reviews or meta-analysis of cohort studies; 2b: Evidence obtained from individual cohort studies; 3a: Evidence obtained from systematic reviews or meta-analysis of case-control studies; 3b: Evidence obtained from individual case-control studies; 4: Evidence obtained from case series; and 5: Evidence obtained from expert opinions.

Study registration

This systematic review has been registered in the PROSPERO Database of the National Institute for Health Research, ID 328537 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

RESULTS

An initial search found 1,445 references (see Fig. 1). After checking for duplicate records, the initial number of articles included in the first step of the review was 1,292. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 63 articles underwent full-text review. Finally, 43 articles were excluded: 40 articles did not assess type D personality; 2 did not assess skin diseases; and 1 did not include patients. Finally, 20 studies, including a total of 3,124 participants, met the eligible criteria and were included in the review (Table SIII). The main tool used to assess the presence of type D personality was the DS14 questionnaire (5). The association of type D personality with disease severity, poorer quality of life and psychological comorbidities for each diseases group is discussed below.

Acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa

A range of articles addressed the issue of type D personality in patients with acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa. Regarding the prevalence of this personality and its relationship with disease severity, Chilicka et al. (2) showed higher rates of type D personality in patients with acne vulgaris compared with controls (40.67% vs 15.67%). Similar results were found by Sereflican et al. (21), who also described a lack of correlation between acne severity and type D personality: patients with type D personality and those without type D personality seemed to have similar severity of acne.

On the other hand, the impact of this type of personality on the quality of life of patients with acne was also studied by Chilicka et al. (2), who found that both components of type D personality (NA and SI) were associated with lower life satisfaction. Krowchuk et al. (22) studied the impact of acne in adolescent patients, showing that up to 53% of patients had self-reported SI due to the acne. No differences were found between males and females. Regarding hidradenitis suppurativa, Ramos-Alejo Pita et al. (23) performed a cross-sectional study of patients and cohabitants. It was found that the presence of NA correlated with lower rates of quality of life in both patients and cohabitants.

Finally, regarding type D personality and psychological comorbidities, Sereflican et al. (21) found that type D personality in patients with acne was associated with higher rates of anxiety, depression, and higher perceived stress.

Psoriasis

The prevalence of type D personality in patients with psoriasis was studied by Molina-Leyva et al. (20). The authors found a higher prevalence of type D personality in patients with psoriasis than in controls (38.7% vs 23.7%). Similar results were shown by Basinska et al. (24). In addition, this study found that the differences in type D personality, SI and NA prevalence were higher for females than for males. Therefore, female patients with psoriasis could be more socially inhibited and could have more negative effects than male patients with psoriasis.

Regarding disease severity and type D personality, 2 studies by Aguayo-Carreras et al. (25, 26) were analysed. The first is a cross-sectional study, where no association was found between psoriasis severity and type D personality. The second shows a prospective cohort of patients with moderate-severe psoriasis, which was analysed over time, up to week 208. It was shown that type D personality was a stable personality trait over time in up to 47.5% of the patients with psoriasis. Moreover, worse disease severity at week 208 was associated with type D personality stability.

The issue of quality of life and type D personality was also addressed by Molina-Leyva et al. (20), Aguayo-Carreras et al. (26), Tekin et al. (27) and Van Beugen et al. (28). These studies showed that type D personality is associated with an impaired general, sexual and psoriasis HRQoL in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. This was found for many subscales: general, functional, physical, mental, vitality, pain and social. Moreover, type D personality was associated with higher rates of sleep disorders and early awakening and can be considered a strong predictor for higher levels of perceived stigmatization.

Finally, the relationship between type D personality and psychological comorbidities was explored in the studies by Molina-Leyva et al. (20) and Aguayo-Carreras et al. (25, 26). These authors showed that type D personality is associated with higher risk of anxiety (up to 3.2-fold) and higher rates depression both at baseline and at week 208. Therefore, the association of type D personality with mood disturbances seems to be stable over time.

Skin cancers

Regarding skin cancers, the studies reviewed only explored the impact of type D personality in patients with melanoma. No studies were found evaluating the prevalence of type D personality in patients with this neoplasm. In relation to the severity of the disease, Mols et al. (29) analysed a sample of 562 melanoma survivors. They found no differences in Breslow thickness, stage at diagnosis, or primary treatment between type D personality and non-type D personality patients. However, a selection bias is expected, as the study was based only on melanoma survivors, and did not include deceased patients. In this regard, White et al. (30) studied a prospective cohort of patients to evaluate the development of cancer. They found that negative affect of patients was not associated with the development of melanoma.

On the other hand, the impact of this personality trait on quality of life was also explored by Mols et al. (29), who found that melanoma survivors with type D personality had worse quality of life in all of the subscales measured. Moreover, patients with type D personality showed a greater impact on all of the items of the Impact of Cancer Questionnaire.

Finally, no studies addressed psychological comorbidities in patients with skin cancer and type D personality.

Other skin diseases

Studies exploring the impact of type D personality on patients with other skin diseases were also found, including isolated itching of the auditory canal, chronic spontaneous urticaria and vitiligo.

On the one hand, Yilmaz et al. (31) performed a study addressing the impact of type D personality on patients with isolated itching of the auditory canal and controls. Type D personality rates were higher in patients with isolated itching of the external auditory canal than in controls (43% vs 15%). Moreover, it was found that type D personality was associated with greater severity of itch as an independent factor, and was also associated with higher anxiety rates in these patients.

On the other hand, Sanchez-Diaz et al. (32) assessed type D personality in a cross-sectional sample of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. The results show that type D personality was not associated with disease severity. However, it was related to worse quality-of-life indexes (including most Dermatology Life Quality Index subscales), and to worse sleep quality (Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire and Pittsburg Sleep Quality index). Finally, type D personality was associated with higher rates of anxiety and depression in these patients (the prevalence of anxiety was increased by 51% and depression by 86%).

Finally, Atis et al. (33) showed that patients with vitiligo and type D personality, but not those with alopecia areata, had poorer quality of life. In this study it was also found that type D personality scores correlated to higher anxiety and depression scores in patients with alopecia areata and those with vitiligo.

DISCUSSION

Type D personality seems to have a strong correlation with poorer quality of life and higher rates of psychological comorbidities in patients with skin diseases. Both SI and NA might play a role in the development of poorer quality of life, anxiety or depression. Moreover, the relationship between type D personality and poorer outcomes in personal disease management might be of great clinical interest, in proposing a holistic approach to cutaneous disease.

As described previously, various studies have assessed show how type D personality tends to be more frequent among patients with skin diseases compared with controls: acne patients (2), psoriasis patients (20) or patients with isolated itch of external auditory canal (31) show this tendency. However, due to the epidemiological design, these studies are not sufficient to establish causality. Similar results have been found for other diseases, such as myocardial infarction (8). However, it is not known whether type D personality is a consequence of the skin diseases or if it plays a role in the aetiopathogenesis of the diseases. In this regard, the presence of dysfunctional personality traits could lead to an increased predisposition to stress, and thus to the triggering of certain skin diseases.

Moreover, recent articles show how type D personality components, SI and NA, could be explained as a consequence of the diseases (34). In this regard, the disease itself would be responsible for depression and poor quality of life, which would lead to higher NA scores, and a higher probability of being classified as type D personality. Future studies including longitudinal follow-up would be of special interest to clarify this psychological causality chain. Moreover, as can be seen in Table SI, although SI and NA are measured in most of the articles included in the review, most studies define type D personality using a dichotomous method (“presence” or “absence” of type D personality). As described previously by Lodder et al. (35), the continuous approach to type D personality seems to be more accurate; hence, this should be the method of choice in future studies evaluating the impact of type D personality.

In addition, type D personality has also been linked to poorer outcomes and poorer quality of life in healthy individuals (6). It is not known whether the disease has a synergistic effect with type D personality impairing quality of life of patients, or, on the contrary, whether it has the same effect on healthy and diseased individuals.

Type D personality also appears to have a close correlation with quality of life in patients with dermatological diseases. All of the studies evaluated show that patients with type D personality tend to experience worse HRQoL.

Similar results have been found in the current review for type D personality and psychological comorbidities. Mood status disturbances, such as anxiety or depression, seem to be more frequent among patients with type D personality compared with those without type D personality, regardless of the disease in question. These associations also seem to be comparable for other diseases, such as breast cancer (36). This could be of great interest because the detection of type D personality in patients with skin diseases could be an interesting way of detecting patients who are at a higher risk of having psychological disorders regardless of the disease severity. These patients, therefore, would not be detected by means of severity scores for each disease.

Given the results of this review, the use of screening for the presence of type D personality, using questionnaires validated in specific dermatology units, could be considered. This approach would make it possible to select those patients who are likely to require greater attention to their quality of life and mood, regardless of the severity of their skin disease. In addition, the DS14 questionnaire (5), which has been used in most of the published studies, is a quick and accessible questionnaire that would allow screening to be performed during consultation with a dermatologist.

The main limitation of the current review is the quality of the studies included in the review. Most of them are cross-sectional studies, which makes them inadequate for assessing causality. Moreover, the statistical power of the studies included in the review may have been insufficient to detect some differences. Due to the lack of homogeneity of the variables measuring quality of life and mood among the different studies, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis.

Future research should focus on the current gaps in research. Studies that prospectively evaluate the relationship of type D personality from an early age with the presence and severity of skin diseases would be of great interest. Moreover, the development of studies to evaluate the utility of using type D personality questionnaires as a screening method in dermatology units could be a way to improve clinical practice.

In conclusion, type D personality appears to be a marker of patients who are at increased risk of poorer quality of life and higher rates of psychological comorbidities in a wide variety of skin diseases. Screening for this personality trait could be useful to detect patients with a greater predisposition to psychological disorders and poorer quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This review will be part of the doctoral thesis of the author Manuel Sánchez-Diaz.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- McLean KC. Stories of the young and the old: personal continuity and narrative identity. Dev Psychol 2008; 44: 254–264.

- Chilicka K, Rogowska AM, Szyguła R, Adamczyk E. Association between satisfaction with life and personality types A and D in young women with acne vulgaris. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 8524.

- Mahoney CB, Lea J, Schumann PL, Jillson IA. Turnover, burnout, and job satisfaction of certified registered nurse anesthetists in the United States: role of job characteristics and personality. AANA J 2020; 88: 39–48.

- Friedman HS. The multiple linkages of personality and disease. Brain Behav Immun 2008; 22: 668–675.

- Denollet J. DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosom Med 2005; 67: 89–97.

- Mols F, Denollet J. Type D personality in the general population: a systematic review of health status, mechanisms of disease, and work-related problems. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010; 8: 9.

- Raykh OI, Sumin AN, Kokov АN, Indukaeva EV, Artamonova GV. Association of type D personality and level of coronary artery calcification. J Psychosom Res 2020; 139: 110–265.

- Manoj MT, Joseph KA, Vijayaraghavan G. Type D personality and myocardial infarction: a case-control study. Indian J Psychol Med 2020; 42: 555–559.

- Condén E, Rosenblad A, Wagner P, Leppert J, Ekselius L, Åslund C. Is type D personality an independent risk factor for recurrent myocardial infarction or all-cause mortality in post-acute myocardial infarction patients? Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017; 24: 522–533.

- Pedersen SS, Holkamp PG, Caliskan K, van Domburg RT, Erdman RAM, Balk AHMM. Type D personality is associated with impaired health-related quality of life 7 years following heart transplantation. J Psychosom Res 2006; 61: 791–795.

- Saeed T, Niazi GSK, Almas S. Type-D personality: a predictor of quality of life and coronary heart disease. East Mediterr Heal J 2011; 17: 46–50.

- Kim SR, Nho J-H, Kim HY, Ko E, Jung S, Kim I-Y, et al. Type-D personality and quality of life in patients with primary brain tumours. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2021; 30: e13371.

- Kim SR, Nho J-H, Nam J-H. Relationships among Type-D personality, symptoms and quality of life in patients with ovarian cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2018; 39: 289–296.

- Mizutani S, Ekuni D, Yamane-Takeuchi M, Azuma T, Taniguchi-Tabata A, Tomofuji T, et al. Type D personality and periodontal disease in university students: a prospective cohort study. J Health Psychol 2018; 23: 754–762.

- Gębska M, Dalewski B, Pałka Ł, Kołodziej Ł, Sobolewska E. The importance of type D personality in the development of temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) and depression in students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Sci 2021; 12: 28.

- Jordi SBU, Botte F, Lang BM, Greuter T, Krupka N, Auschra B, et al. Type D personality is associated with depressive symptoms and clinical activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021; 54: 53–67.

- Garİp Y, GÜler T, Bozkurt Tuncer Ö, Önen S. Type D personality is associated with disease severity and poor quality of life in Turkish patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Arch Rheumatol 2020; 35: 13–19.

- Lin Y-H, Chen D-A, Lin C, Huang H. Type D personality is associated with glycemic control and socio-psychological factors on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2020; 13: 373–381.

- Barone S, Bacon SL, Campbell TS, Labrecque M, Ditto B, Lavoie KL. The association between anxiety sensitivity and atopy in adult asthmatics. J Behav Med 2008; 31: 331–339.

- Molina-Leyva A, Caparros-delMoral I, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, Naranjo-Sintes R, Jimenez-Moleon JJ. Elevated prevalence of Type D (distressed) personality in moderate to severe psoriasis is associated with mood status and quality of life impairment: a comparative pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 1710–1717.

- Sereflican B, Tuman TC, Tuman BA, Parlak AH. Type D personality, anxiety sensitivity, social anxiety, and disability in patients with acne: a cross-sectional controlled study. Postep Dermatologii i Alergol 2019; 36: 51–57.

- Aguayo-Carreras P, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Molina-Leyva A. Four years stability of type D personality in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and its implications for psychological impairment. An Bras Dermatol 2021; 96: 558–564.

- Aguayo-Carreras P, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, Molina-Leyva A. Type D personality is associated with poor quality of life, social performance, and psychological impairment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: a cross-sectional study of 130 patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2020; 86: 375–381.

- Basińska MA, Woźniewicz A. The relation between type D personality and the clinical condition of patients suffering from psoriasis. Postep Dermatologii i Alergol 2013; 30: 381–367.

- Mols F, Holterhues C, Nijsten T, van de Poll-Franse L V. Personality is associated with health status and impact of cancer among melanoma survivors. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46: 573–580.

- White VM, English DR, Coates H, Lagerlund M, Borland R, Giles GG. Is cancer risk associated with anger control and negative affect? Findings from a prospective cohort study. Psychosom Med 2007; 69: 667–674.

- Yilmaz B, Canan F, Şengül E, Özkurt FE, Tuna SF, Yildirim H. Type D personality, anxiety, depression and personality traits in patients with isolated itching of the external auditory canal. J Laryngol Otol 2016; 130: 50–55.

- Sánchez-Díaz M, Salazar-Nievas M-C, Molina-Leyva A, Arias-Santiago S. Type D personality is associated with poorer quality of life in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a cross-sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol 2022; 102: adv00734.

- Krowchuk DP, Stancin T, Keskinen R, Walker R, Bass J, Anglin TM. The psychosocial effects of acne on adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol 1991; 8: 332–338.

- Ramos-Alejos-Pita C, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A. Quality of life in cohabitants of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 6000.

- Tekin A, Atis G, Yasar S, Goktay F, Aytekin S. The relationship of type D personality and quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study in turkish population. Acta Medica Mediterr 2018; 34: 1009–1013.

- van Beugen S, van Middendorp H, Ferwerda M, Smit J V, Zeeuwen-Franssen MEJ, Kroft EBM, et al. Predictors of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 687–694.

- Atis G, Tekin A, Ferhatoglu ZA, Goktay F, Yasar S, Aytekin S. Type D personality and quality of life in alopecia areata and vitiligo patients: a cross-sectional study in a Turkish population. Turkderm-Turkish Arch Dermatology Venerol 2021; 55: 87–91.

- Lodder P, Kupper N, Antens M, Wicherts JM. A systematic review comparing two popular methods to assess a Type D personality effect. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2021; 71: 62–75.

- Lodder P. Modeling synergy: how to assess a Type D personality effect. J Psychosom Res 2020; 132: 109990.

- Grassi L, Caruso R, Murri MB, Fielding R, Lam W, Sabato S, et al. Association between Type-D personality and affective (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress) symptoms and maladaptive coping in breast cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2021; 17: 271–279.

- Panasiti MS, Ponsi G, Violani C. Emotions, alexithymia, and emotion regulation in patients with psoriasis. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 836.

- Lim DS, Bewley A, Oon HH. Psychological profile of patients with psoriasis. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2018; 47: 516–522.

- Mols F, Denollet J. Type D personality among noncardiovascular patient populations: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010; 32: 66–72.

- Sanchez-Diaz M, Salazar-Nievas M-C, Molina-Leyva A, Arias-Santiago S, Sánchez-Díaz M, Salazar-Nievas M-C, et al. The burden on cohabitants of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 3228.