Several melanoma-specific dermoscopic features have been described, some of which have been reported as indicative of in situ or invasive melanomas. To assess the usefulness of these features to differentiate between these 2 categories, a retrospective, single-centre investigation was conducted. Dermoscopic images of melanomas were reviewed by 7 independent dermatologists. Fleiss’ kappa (κ) was used to analyse interobserver agreement of predefined features. Logistic regression and odds ratios were used to assess whether specific features correlated with melanoma in situ or invasive melanoma. Overall, 182 melanomas (101 melanoma in situ and 81 invasive melanomas) were included. The interobserver agreement for melanoma-specific features ranged from slight to substantial. Atypical blue-white structures (κ=0.62, 95% confidence interval 0.59–0.65) and shiny white lines (κ=0.61, 95% confidence interval 0.58–0.64) had a substantial interobserver agreement. These 2 features were also indicative of invasive melanomas >1.0 mm in Breslow thickness. Furthermore, regression/peppering correlated with thin invasive melanomas. The overall agreement for classification of the lesions as invasive or melanoma in situ was moderate (κ=0.52, 95% confidence interval 0.49–0.56).

Key words: dermoscopy; melanoma; observer variation; predictive value of tests; reproducibility of results; retrospective study.

Accepted Oct 1, 2021; Epub ahead of print Oct 1, 2021

Acta Derm Venereol 2021; 101: adv00570.

doi: 10.2340/actadv.v101.281

Corr: Sam Polesie, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gröna stråket 16, SE-413 45 Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: sam.polesie@vgregion.se

SIGNIFICANCE

Dermoscopy improves dermatologists’ assessment of skin tumours, including melanoma. Specific dermoscopic features that may guide dermatologists in deciding whether a melanoma is thick or thin have been proposed, but little is known about how well dermatologists agree on their presence (or absence) in a preoperative setting, which must be considered instrumental for their clinical transferability. This study highlights that 2 specific features, shiny white lines and atypical blue-white structures, both display moderate to substantial interobserver agreement between dermatologists and are suggestive of thicker melanomas, while regression/peppering are more indicative of thinner lesions. Overall agreement between dermatologists in classifying lesions as invasive or in situ was moderate.

INTRODUCTION

Dermoscopy is an invaluable tool for the diagnosis of skin tumours, including melanomas. Over the years, a comprehensive list of dermoscopic features that are suggestive of melanoma has been compiled, and efforts have been made in terms of standardization of the terminology used (1). The presence of specific dermoscopic features has also been shown to be indicative of whether melanomas are in situ (MIS) or invasive, and may even be suggestive of Breslow thickness (2–4). Nevertheless, little is known about how well dermatologists agree on the presence (or absence) of these specific features, which must be considered as a prerequisite for their validity and clinical transferability. Moreover, investigations into interobserver agreement between different readers (i.e. study participants) most often have two important limitations. Firstly, they often lack complete descriptions of the individual responses to all of the images analysed. Secondly, they most often do not include the image data set used. These both factors preclude other researchers from reviewing and learning from the published observations. Finally, while a consensus agreement regarding specific findings is often presented, researchers do not always specify how the group of readers reached this agreement.

The primary objective of this study was to explore dermatologists’ agreement in identifying predefined melanoma-specific dermoscopic features. The secondary objective was to identify which of these features correlated with MIS vs invasive melanomas as well as MIS or thin invasive (i.e. Breslow thickness ≤ 1.0 mm) melanomas vs thicker melanomas (i.e. Breslow thickness > 1.0 mm). Thin melanomas were defined as melanomas with a tumour pathological stage of 1 (pT1) (5).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective, single-centre investigation was performed, including primary melanomas with available dermoscopic images obtained from the department of dermatology at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. Dermoscopic images were obtained using a smartphone or camera set up (iPhone models 7 plus and 8 plus, Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA or Canon PowerShot, Canon, Canon Inc., Ōta, Tokyo, Japan) and DermLite dermatoscopes DL3N, DL4 and Foto (3 Gen Inc., San Juan Capistrano, CA, USA). All images were obtained using the polarized light setting.

Images with suboptimal quality and melanomas that were previously partially biopsied were excluded. Lesions in the head and neck region and larger lesions that could not be captured with a single dermoscopic image were also excluded. All tumours were histopathologically diagnosed by dermatopathologists. The lesions were removed in the time-period 1 January 2017 to 29 February 2020. The study was approved by the regional ethics review board in Gothenburg, University of Gothenburg (approval number 283-18).

One resident and 6 board-certified dermatologists independently analysed all images on their personal computer screens. Their experience ranged from 3.5 to 17 years (median 10 years). All participating dermatologists had a particular interest in skin cancer diagnosis and had previously received formal training in dermoscopy in addition to their daily use of dermoscopy in routine clinical practice. Before study initiation, the selected dermoscopic features were presented and discussed at a consensus meeting, which was also recorded and made available to all readers for reference purposes. Overall, 15 specific dermoscopic features were selected (Fig. 1). The features were adapted from previous publications applying a similar approach (6, 7). The primary objective of the 7 readers was to decide which dermoscopic features were present in each lesion. Moreover, for each lesion, the dermatologists needed to make a prediction of whether they believed the lesion was invasive or MIS. If the dermatologist selected invasive melanoma, an estimation of melanoma Breslow thickness was required (i.e. ≤ 1.0 or > 1.0 mm).

To restrict the evaluation to dermoscopic features, no metadata or clinical images were made available. The primary outcome measure was the interobserver agreement for each dermoscopic feature.

The secondary outcomes were to analyse: (i) which features correlated with MIS and invasive melanomas, respectively; (ii) which features correlated with thin melanomas (i.e. lesions with a Breslow thickness ≤ 1.0 mm including MIS) and melanomas with a Breslow thickness > 1.0 mm, respectively; (iii) the interobserver agreement among the dermatologists in their prediction of melanoma thickness.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using R version 3.5.3 (https://www.r-project.org/). To measure interobserver agreement between the 7 readers, Fleiss’ kappa (κ) was used (8). The agreement (κ-value) was interpreted as poor (< 0), slight (0–0.2), fair (> 0.2–0.4), moderate (> 0.4–0.6), substantial (> 0.6–0.8) or almost perfect (> 0.8) (9). Logistic regression and odds ratios (ORs) were used to assess whether specific features correlated with MIS or invasive melanomas as well as melanomas less than or greater than 1.0 mm in thickness, respectively. For these analyses, each lesion was given 15 scores (1 score per dermoscopic structure) pertaining to the proportion of dermatologists that included that specific dermoscopic structure in their assessment (i.e. ranging from 0 to 7 out of 7). All tests were 2-sided and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Overall, 182 melanomas (101 MIS (55%) and 81 invasive (45%) melanomas) were independently reviewed by all dermatologists. Among the invasive melanomas, 59 (73%) had a Breslow thickness ≤ 1.0 mm (Table I). The median age (interquartile range) of the included patients was 68.5 years (52.0–76.0 years) and 53.3% were males. Overall, 103 (57%), 50 (27%) and 29 (16%) of the melanomas were located on the trunk, the upper and lower extremities, respectively. All included dermoscopic images are shown in Appendix S1.

When combining all 1,274 assessments (707 and 567 unique evaluations for MIS and invasive melanomas, respectively), regression/peppering (44.7%), atypical network (36.4%) and atypical dots/globules (36.1%) were the most commonly observed structures. For invasive melanomas, atypical blue-white structures (ABWS) (49.2%; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 45.1–53.3%) and shiny white lines (SWL) (42.0%; 95% CI 38.0–46.1%) were the most common findings (Fig. 2, Table SI). The overall agreement in classification of the lesions as invasive or MIS was moderate (κ = 0.52, 95% CI 0.49–0.56). When expanding this classification problem to 3 classes (i.e. MIS, invasive melanomas ≤ 1.0 mm, and invasive melanomas >1.0 mm) the corresponding κ-value was 0.44 (95% CI 0.42–0.47).

The κ-value (interobserver agreement) for the individual features ranged from 0.15 (slight) to 0.65 (substantial). Moderate to substantial interobserver agreement was observed for ABWS (κ = 0.62, 95% CI 0.59–0.65) and SWL (κ = 0.61, 95% CI 0.58–0.62), whereas negative network exhibited substantial interobserver agreement (κ = 0.65, 95% CI 0.61–0.68) (Fig. 3).

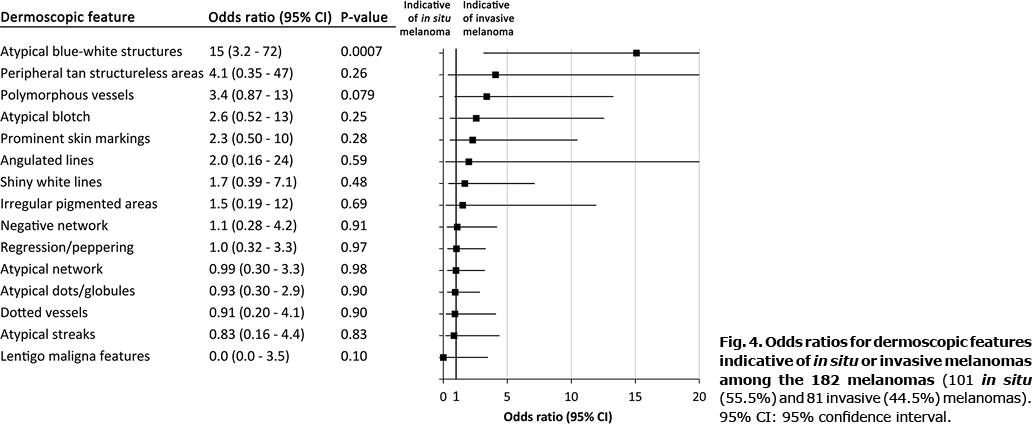

When analysing which features were suggestive of MIS or invasive melanomas, presence of ABWS (OR 15, 95% CI 3.2–72) correlated with invasive disease. Albeit not significant, there was also a trend for polymorphous vessels (PV) (OR 3.4 95% CI 0.9–13). No positive correlation was observed between any feature and MIS (Fig. 4).

Finally, MIS and thin invasive (i.e. ≤ 1.0 mm) melanomas combined (n = 160) were compared with thick invasive (i.e. >1.0 mm) melanomas (n = 22). Regression/peppering was identified more often in the combined group of MIS and thin invasive lesions (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.06–0.93), while ABWS (OR 5.7, 95% CI 1.4–24) and SWL (OR 5.5, 95% CI 1.2–25) were more indicative of melanoma with a Breslow thickness > 1.0 mm (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

In this investigation, 11 out of 15 predefined melanoma-specific dermoscopic features displayed at least moderate interobserver agreement. Among these, ABWS, negative network and SWL exhibited moderate to substantial interobserver agreement, underlining their clinical transferability. Of these, ABWS must be considered particularly useful, as this feature also correlated significantly with invasive melanoma. Interestingly, no specific feature correlated with MIS. Although regression/peppering correlated with the combined group of MIS and thin invasive melanomas, the interobserver agreement was moderate pertaining to this specific feature. Two features (ABWS and SWL) were more prevalent in melanomas with a Breslow thickness > 1.0 mm.

In their study on dermoscopic features of MIS, Lallas et al. (3) observed interobserver agreement ranging from fair to substantial for each included feature/pattern, with κ values as high as 0.77 for prominent skin markings and as low as 0.39 for atypical network. Nevertheless, it is uncertain how the group of 3 independent readers reached the consensus that was ultimately presented in their paper. In a retrospective web-based study by Carrera et al. (10) including 5,670 unique evaluations of 358 naevi and 119 melanomas by 130 readers, both negative network and shiny white structures were suggestive of melanoma. However, the interobserver agreement for these 2 features was only slight.

In the current investigation, ABWS was the only finding that was indicative of invasive melanoma, whereas a trend was also observed for PV. A correlation between ABWS and invasive disease was also observed in the studies by Lallas et al. (3) and Silva et al. (2), but they saw no correlation between PV and invasive melanoma. In an investigation by Argenziano et al. (4) including 72 MIS/thin melanomas (19 MIS and 53 invasive melanomas with a Breslow thickness < 0.76 mm) and 50 thicker melanomas (Breslow thickness ≥ 0.76 mm), grey-blue areas (similar to ABWS) and atypical vascular pattern (similar to PV) were more suggestive of thicker lesions. When comparing thin melanomas including MIS lesions with melanomas thicker than 1.0 mm, SWL was also a feature significantly associated with thick melanomas in the current study. Silva et al. (2) did not include this feature and, in the study by Lallas et al. (3), most images were obtained without polarized light, thus precluding possible comparisons. As in the current study, SWL has previously been described more often in invasive melanomas, especially in melanomas ≥ 1.0 mm Breslow (11). Interestingly, the current study observed SWL in 13.3% of all MIS. We hypothesize that the background colour surrounding the SWL may guide readers in their diagnostic decision. For example, SWL on a brown background in a flat lesion may be common in MIS, while SWL on a blue background is probably more strongly associated with invasive melanoma. In another investigation including 144 melanomas, invasive melanomas with SWL had a greater Breslow depth compared with those that did not present with this feature. Moreover, this structure was observed more often in invasive melanomas (37%) compared with MIS (18%), a difference that was not statistically significant (12). Furthermore, this proportion of SWL for MIS and invasive melanomas was similar to that in the current study.

Although no specific dermoscopic feature correlated with MIS, this may be explained by the fact that invasive melanomas can present with portions of the lesion that are still MIS (13, 14). Thus, dermoscopic features that may in fact be indicative of MIS, may also be present in invasive melanomas. Another reason why no specific features were indicative of MIS might have been that we did not compare naevi with MIS. In the study by Lallas et al. (3), which included 325 MIS and 312 atypical naevi, both irregular hyperpigmented areas and prominent skin markings were more suggestive of MIS. In the current investigation, however, prominent skin markings and irregular hyperpigmented areas were not helpful in distinguishing between MIS and invasive melanomas. Finally, the current study observed a correlation between regression/peppering and thin or MIS. Lallas et al. (3) similarly observed that extensive regression covering > 50% of the lesion correlated with MIS compared with invasive melanomas (n = 102). In a study by Seidenari et al. (15), the presence of 11 different parameters of regression were assessed in 85 dermoscopically equivocal lesions with a histological diagnosis of naevus, 85 MIS and 85 invasive melanomas. All lesions were evaluated by 3 readers who independently assessed the features. Overall regression of dermoscopic features were more commonly observed in MIS and equivocal naevi compared with invasive melanomas. In the study by Silva et al. (2), signs of regression, such as white scar-like areas and peppering, were infrequently observed, making it precarious to draw any firm conclusions about these features and their correlation with melanoma thickness in their cohort.

Interestingly, predefined dermoscopic algorithms improve physicians’ capability of diagnosing melanoma, despite the fact that melanomas can look very different depending on subtype, location and skin type. On the other hand, when a reader analyses an image, human cognitive assessment is prone to several biases, including ascertainment bias, confirmation bias and search satisfying bias (16, 17).

Identifying specific and sensitive features relating to melanoma thickness that also have a high level of interobserver agreement is mainly important for physicians in a pre-operative setting. Such features may influence what prognostic information is given to the patient prior to the diagnostic excision and may also guide the surgeon in determining the optimal initial surgical margins. Moreover, specific findings, such as regression/peppering, might be an appealing feature to identify, since histopathological regression was recently linked to a more favourable outcome in patients with primary stage I and II melanomas (18). In the current investigation, regression/peppering was a commonly observed feature among the included melanomas; however, the interobserver agreement for this specific feature was only moderate.

Limitations and strengths

This study has some limitations. The readers were all affiliated with the same academic setting and a consensus meeting was arranged to define and discuss all structures prior to study initiation. Consequently, the agreement (albeit predominantly moderate) might have been somewhat higher than in a real-life setting. Moreover, this was a retrospective investigation, in which physicians knew that the included lesions were either MIS or invasive melanomas. Nevertheless, the objective was to find identifiers suggestive of any of these 2 categories. With regard to comparisons between MIS or thin invasive melanomas and thick invasive melanomas, the number of thick invasive melanomas was relatively low, which may have affected outcomes.

While the dermoscopic features included in the current study all came from the revised 2-step algorithm, we acknowledge that other algorithms with a somewhat different set of features might have generated different results. All tissue specimens from the lesions were analysed by a dermatopathologist. Even though challenging melanoma cases are often discussed in a team setting at our hospital, a systematic consensus reporting for all included lesions could have resulted in a somewhat different final diagnosis in some cases. Moreover, we acknowledge the inherent difficulties in discriminating between MIS and thin invasive melanomas, which was the reason behind merging these into the group of thin invasive melanomas. Most of the included patients were of Nordic origin, which also must be considered with regard to the external validity of the results. It is likely that the distribution of melanoma-specific dermoscopic features might be different in other populations with other skin types and baseline exposures to ultraviolet light. This might also have affected the interobserver agreement. Moreover, all included lesions were distributed on the upper and lower extremities, and the trunk, making it difficult to draw specific conclusions for head and neck lesions that generally display other features and thus are often analysed separately. In addition, larger lesions, not captured completely by one dermoscopic image alone, were excluded, which must also be considered in terms of external validity. In the current investigation, invasive melanomas ≤ 1.0 mm were considered as thin. In Sweden, sentinel node biopsy is recommended for invasive melanomas > 1.0 mm (19); however, we acknowledge that in other countries sentinel node biopsy is also recommended for lesions ≥ 0.8 mm with additional risk factors (20). In the current cohort, only 1 lesion ≤ 1.0 mm was ulcerated.

Moreover, for this investigation, we did not use standardized equipment for image review, and this could have interfered with the results. Notably, this investigation included only 182 lesions and 7 readers and, as such, the CIs were wide. Future studies, including more lesions and readers, will be important to examine these findings. Finally, the readers were not asked to mark the findings they identified on the study images. Sharing annotated worksheets is rare, but could have improved the reproducibility of the current results.

A strength of this study is that more observers and melanomas were included compared with previous similar investigations (4, 21, 22). While other investigations have focused primarily on describing specific dermoscopic features in MIS and invasive melanomas, the aim of the current study was to assess their usefulness in making precise diagnostic predictions. Moreover, the dermoscopic images evaluated in this study are all shared, which is rare but instrumental for transparency in dermoscopy research. We acknowledge that it was technically more challenging to share all analysed images in the 1990s and at the beginning of the new millennium, when many of the previous investigations relating to dermoscopic features were undertaken,. However, it is very easy to publish these in online supplements nowadays. We strongly believe this ought to be a requirement of future studies addressing dermoscopic features and interobserver agreement.

We recognize that the identification of specific dermoscopic features is subjective. Consequently, we used a score rather than a consensus reporting on the presence or absence of the included dermoscopic features. This method provides a less biased and more conservative reporting of the identified features. To the best of our knowledge, this approach to describing dermoscopic features is novel, but may be considered a more useful way of assessing specific features.

Conclusion

To summarize, this investigation highlights that most melanoma-specific dermoscopic features display moderate interobserver agreement. Among all 15 features included, ABWS and SWL displayed substantial interobserver agreement and were both indicative of melanomas with a Breslow thickness > 1.0 mm. Although no features were suggestive of MIS specifically, regression/peppering was indicative of MIS or thin melanomas as a combined group. Overall, this investigation is a reminder that, while dermoscopic algorithms are frequently used worldwide, critical and continuous assessment of their clinical transferability is important.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was financed by grants from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils, the ALF-agreement (ALFGBG-728261).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Kittler H, Marghoob AA, Argenziano G, Carrera C, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, et al. Standardization of terminology in dermoscopy/dermatoscopy: results of the third consensus conference of the International Society of Dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 1093–1106.

- Silva VP, Ikino JK, Sens MM, Nunes DH, Di Giunta G. Dermoscopic features of thin melanomas: a comparative study of melanoma in situ and invasive melanomas smaller than or equal to 1mm. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 2013; 88: 712–717.

- Lallas A, Longo C, Manfredini M, Benati E, Babino G, Chinazzo C, et al. Accuracy of dermoscopic criteria for the diagnosis of melanoma in situ. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 414–419.

- Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, De Giorgi V, Delfino M. Clinical and dermatoscopic criteria for the preoperative evaluation of cutaneous melanoma thickness. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999; 40: 61–68.

- Isaksson K, Mikiver R, Eriksson H, Lapins J, Nielsen K, Ingvar C, et al. Survival in 31670 patients with thin melanomas: a Swedish population-based study. Br J Dermatol 2021; 184: 60–67.

- Maskalane J, Salijuma E, Lallas K, Papageorgiou C, Gkentsidi T, Manoli MS, et al. Distribution of the dermoscopic features of melanoma of trunk and extremities according to the anatomic sublocation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84: 1717–1719.

- Marghoob AA, Braun R. Proposal for a revised 2-step algorithm for the classification of lesions of the skin using dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146: 426–428.

- Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull 1971; 76: 378.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–174.

- Carrera C, Marchetti MA, Dusza SW, Argenziano G, Braun RP, Halpern AC, et al. Validity and reliability of dermoscopic criteria used to differentiate nevi from melanoma: a web-based international dermoscopy society study. JAMA Dermatol 2016; 152: 798–806.

- Shitara D, Ishioka P, Alonso-Pinedo Y, Palacios-Bejarano L, Carrera C, Malvehy J, et al. Shiny white streaks: a sign of malignancy at dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions. Acta Derm Venereol 2014; 94: 132–137.

- Verzi AE, Quan VL, Walton KE, Martini MC, Marghoob AA, Garfield EM, et al. The diagnostic value and histologic correlate of distinct patterns of shiny white streaks for the diagnosis of melanoma: a retrospective, case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 913–919.

- Dyson SW, Bass J, Pomeranz J, Jaworsky C, Sigel J, Somach S. Impact of thorough block sampling in the histologic evaluation of melanomas. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141: 734–736.

- Bishop J, Tallon B. Number of levels required to assess Breslow thickness in cutaneous invasive melanoma: an observational study. J Cutan Pathol 2019; 46: 819–822.

- Seidenari S, Ferrari C, Borsari S, Benati E, Ponti G, Bassoli S, et al. Reticular grey-blue areas of regression as a dermoscopic marker of melanoma in situ. Br J Dermatol 2010; 163: 302–309.

- Ko CJ, Braverman I, Sidlow R, Lowenstein EJ. Visual perception, cognition, and error in dermatologic diagnosis: key cognitive principles. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 81: 1227–1234.

- Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med 2003; 78: 775–780.

- El Sharouni MA, Aivazian K, Witkamp AJ, Sigurdsson V, van Gils CH, Scolyer RA, et al. Association of histologic regression with a favorable outcome in patients with stage 1 and stage 2 cutaneous melanoma. JAMA Dermatol 2021; 157: 166–173.

- Swedish guidelines for malignant melanoma (In Swedish). Last updated: March 19, 2021 Available at:

- https://cancercentrum.se/globalassets/cancerdiagnoser/hud/vardprogram/nationellt-vardprogram-malignt-melanom.pdf.

- Garbe C, Amaral T, Peris K, Hauschild A, Arenberger P, Bastholt L, et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: Treatment – update 2019. Eur J Cancer 2020; 126: 159–177 (in Swedish).

- Carli P, de Giorgi V, Palli D, Giannotti V, Giannotti B. Preoperative assessment of melanoma thickness by ABCD score of dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 43: 459–466.

- Tan E, Oakley A, Soyer HP, Haskett M, Marghoob A, Jameson M, et al. Interobserver variability of teledermoscopy: an international study. Br J Dermatol 2010; 163: 1276–1281.