QUIZ SECTION

A Child with a Congenital Aplasia of the Scalp: A Quiz

Louis DOURS1, Médéric JEANNE2,3, Maya SROUR4 and Sophie LEDUCQ1

1Department of Dermatology and Reference Center for Rare Diseases and Vascular Malformations (MAGEC), University Hospital Center of Tours, Avenue de la République, 37044 Tours Cedex 9, 2Department of Genetics, University Hospital Center of Tours, Tours, 3UMR 1253, iBrain, University of Tours, INSERM, Tours, and 4Department of Pediatric Neurology, University Hospital Center of Tours, Tours, France. E-mail: louis.dours@etu.univ-tours.fr

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2024; 104: adv39948. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v104.39948.

Copyright: © 2024 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

Published: Jun 17, 2024

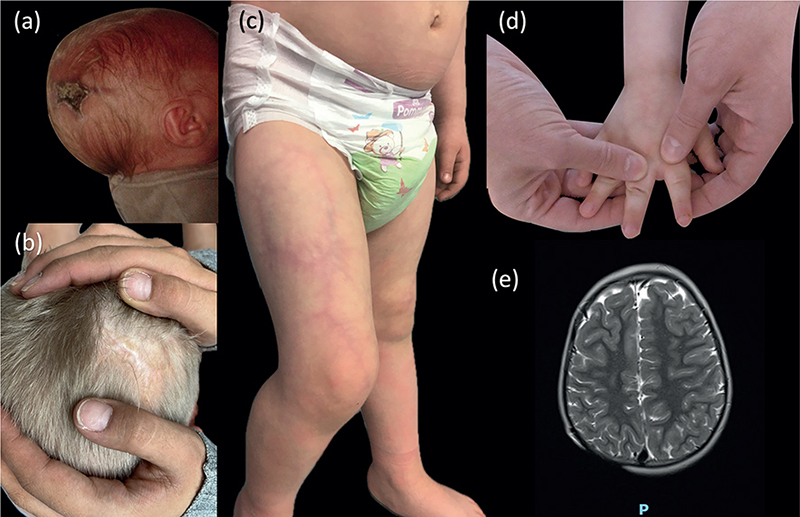

A 3-year-old boy was referred to paediatric dermatology for a congenital aplasia of the scalp. He had no family history and was born at term. He was the second child of non-consanguineous parents. Physical examination showed aplasia cutis congenita of the scalp (Fig. 1A, B). It also revealed reticulated, well-demarcated red-purple plaques, with a coarse fixed livedo pattern that was consistent with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita of the right arm, trunk, and legs (predominantly on the right leg) (Fig. 1C). Brachydactyly with short distal phalanges and mild cutaneous syndactyly was present (Fig. 1D). Neurological evaluation revealed global developmental delay (acquisition of walking at 22 months, disability in fine motor skills, no word association at age 3 years) and epilepsy. Findings were normal for the remaining clinical examination. Brain MRI showed right aplasia cutis with a defect of the bone (Fig. 1E), haemorrhagic lesions of the choroid plexus, and cortico-subcortical atrophy. Results of echocardiography and abdominal ultrasonography were normal. Ophthalmology examination did not reveal any retinal anomalies.

Fig. 1. (a) Scalp defect at birth (aplasia cutis congenita). (b) Aplasia cutis congenita. (c) Cutis marmorata telangiectatica of the right leg. (d) Shortening of terminal phalanges of fingers (brachydactyly). (e) Brain MRI (axial section, T2-weighted image) showing a defect of the parietal bone.

What is your diagnosis?

Differential diagnosis 1: Adams–Oliver syndrome

Differential diagnosis 2: Amniotic band sequence

Differential diagnosis 3: Focal dermal hypoplasia

Differential diagnosis 4: Macrocephaly cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita

See next page for answer.

ANSWERS TO QUIZ

A Child with a Congenital Aplasia of the Scalp: A Commentary

Diagnosis: Adams–Oliver syndrome

Adams–Oliver syndrome (AOS) (OMIM PS100300) is a rare congenital condition characterized by the association of congenital scalp defects (aplasia cutis congenita) and terminal transverse limb defects (1). The estimated incidence is 1 per 250,000 live births (2). Other anomalies associated with AOS include cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (3), dilated tortuous veins on the scalp (3), congenital heart disease (ventricular and atrial septal defects, coarctation of the aorta, bicuspid aorta, etc.) (4), ocular anomalies (retinal detachment, microphthalmia, visual impairment, optic atrophy) (5), and neurological involvement (cognitive disability, spastic hemiplegia or diplegia, seizure) (6). Several pathogenic variants with autosomal dominants forms have been identified (NOTCH1, DLL4, ARHGAP31, RBPJ) as well as autosomal recessive forms (DOCK6, EOGT) (7).

The clinical severity of AOS is heterogeneous, with inter- and intra-familial phenotype variability. Ocular and neurologic anomalies are frequent in patients with DOCK6 variants and heart disease in patients with NOTCH1, DLL4, and RBPJ variants (7). However, only 30% to 50% of patients with AOS have a pathogenic variant (7), and de novo pathogenic variants have been reported, but the frequency is unknown (1). In our patient, genetic analysis did not reveal any pathogenic variant in the genes currently identified in this pathology.

Management requires a multidisciplinary approach (paediatric neurologists, paediatric cardiologists, ophthalmologists, dermatologists, plastic surgeons) for investigation and management. A complete imaging assessment (echocardiography, abdominal ultrasonography, brain MRI) should be performed to detect abnormalities and provide early care (1). In addition, genetic counselling should be offered to families affected by this disease.

REFERENCES

- Hassed S, Li S, Mulvihill J, Aston C, Palmer S. Adams–Oliver syndrome review of the literature: refining the diagnostic phenotype. Am J Med Genet A 2017; 173: 790–800.

- Suarez E, Bertoli MJ, Eloy JD, Shah SP. Case report and review of literature of a rare congenital disorder: Adams–Oliver syndrome. BMC Anesthesiol 2021; 21: 117–121.

- Snape KMG, Ruddy D, Zenker M, Wuyts W, Whiteford M, Johnson D, et al. The spectra of clinical phenotypes in aplasia cutis congenita and terminal transverse limb defects. Am J Med Genet A 2009; 149A: 1860–1881.

- Algaze C, Esplin ED, Lowenthal A, Hudgins L, Tacy TA, Selamet-Tierney ES. Expanding the phenotype of cardiovascular malformations in Adams–Oliver syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2013; 161A: 1386–1389.

- Sukalo M, Tilsen F, Kayserili H, Müller D, Tüysüz B, Ruddy DM, et al. DOCK6 mutations are responsible for a distinct autosomal-recessive variant of Adams–Oliver syndrome associated with brain and eye anomalies. Hum Mutat 2015; 36: 593–598.

- McGoey RR, Lacassie Y. Adams–Oliver syndrome in siblings with central nervous system findings, epilepsy, and developmental delay: refining the features of a severe autosomal recessive variant. Am J Med Genet A 2008; 146A: 488–491.

- Meester JAN, Sukalo M, Schröder KC, Schanze D, Baynam G, Borck G, et al. Elucidating the genetic architecture of Adams–Oliver syndrome in a large European cohort. Hum Mutat 2018; 39: 1246–1261.