REVIEW

Interventions to Reduce Skin-related Self-stigma: A Systematic Review

Juliane TRAXLER, Caroline F. Z. STUHLMANN, Hans GRAF, Marie RUDNIK, Lukas WESTPHAL and Rachel SOMMER

German Center for Health Services Research in Dermatology (CVderm), Institute for Health Services Research in Dermatology and Nursing (IVDP), University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Hamburg, Germany

Self-stigma beliefs are common among people with visible chronic skin diseases and can negatively affect their quality of life and psychosocial well-being. Hence, evidence-based interventions are urgently needed. The objective for this systematic review was to summarize research on available interventions and evaluate their benefits and limitations. Following PRISMA guidelines, an electronic database search of 4 databases (EMBASE, PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science) was conducted. Studies were eligible if they (a) investigated interventions to reduce self-stigma in adults with chronic skin disease, (b) were original empirical articles, and (c) were written in English or German. Two independent reviewers conducted the abstract and full text screening, as well as data extraction. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklists. The initial search yielded 5,811 abstracts; of which 23 records were eligible. Studies addressed a broad range of skin conditions, and interventions ranged from social skills training, counselling and self-help to psychosocial and behavioural interventions. Overall, interventions had mostly positive effects on self-stigma and related constructs. However, the study quality was heterogeneous, and further efforts to develop, thoroughly evaluate, and implement interventions tackling self-stigma in multiple skin conditions and languages are warranted.

SIGNIFICANCE

This systematic review provides an overview of interventions addressing skin disease-related self-stigma, i.e., negative views about oneself and one’s body, and identifies avenues for future research. Specifically, the availability is limited to a few countries and languages, and most programmes were designed for specific skin conditions with a scarcity for inflammatory skin diseases. Moreover, there is a lack of high-quality studies examining their effectiveness. Consequently, there is a need for the development of evidence-based, skin-generic interventions targeting self-stigma in people with skin diseases, which would contribute to improving their psychosocial well-being.

Key words: stigmatization; skin diseases; psoriasis; dermatology; intervention.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2024; 104: adv40384. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v104.40384.

Copyright: © 2024 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

Submitted: Mar 19, 2024; Accepted after revision: Aug 5, 2024; Published: Sep 10, 2024

Corr: Juliane Traxler, Institute for Health Services Research in Dermatology and Nursing (IVDP), University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Martinistraße 52, DE-20246 Hamburg, Germany. E-mail: j.traxler@uke.de

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; funding number: 01GY2105).

INTRODUCTION

Visible chronic skin diseases affect approximately 19% of the German working population (1) and have a large and long-lasting impact on the lives of affected individuals. Alongside the physical discomfort entailing itch, fatigue, pain, and functional limitations (2–4), many patients experience psychological and social impairments. Specifically, body dissatisfaction, depression, embarrassment, social withdrawal, isolation, and low quality of life (QoL) are commonly reported (5–8) (for reviews see [9, 10]). Untreated, these effects can build up over time and lead to cumulative life-course impairment (CLCI), in the worst case forming irreversible damage and preventing those affected from accomplishing their personal goals (11). Consequently, bio-psychosocial approaches are urgently required to alleviate suffering and help people cope with the impact of their chronic skin disease on daily life.

One major challenge in the context of visible differences such as skin diseases is the experience of stigma, both from others (public stigma) and from the individuals themselves (self-stigma). According to the Stage Model of Self-Stigma (12), self-stigma consists of the progressive stages of awareness, agreement, application, and harm. Especially if affected individuals are aware of a stereotype concerning them, agree with it, and apply it to themselves, negative consequences are likely to ensue.

More specifically, this internalization of stigma frequently leads to low levels of self-efficacy and self-esteem (13–15), which, in turn, motivates people to try to hide their skin disease by camouflaging, not disclosing their disease to others, or even avoiding social situations and intimacy (16–18). First studies indicate that self-stigma is one of the main contributors to low QoL in people with dermatological conditions (19, 20), which is supported by moderate to strong correlations between self-stigma and QoL found in persons with HIV (21), mental illness (22–24), and obesity (25). This debilitating impact of self-stigma on quality of life and well-being emphasizes the importance of developing and disseminating interventions targeting self-stigma in persons with visible chronic skin diseases.

In a systematic review on interventions against public and self-stigma related to dermatological conditions, Topp et al. (26) identified 15 studies of mixed quality targeting self-stigma. In light of the World Health Assembly’s call on its member states to take action to improve the acceptance of people with psoriasis (27), there has been an increase in scientific attention to both public and self-stigma, and this has likely intensified efforts in exploring novel interventions in recent years. Furthermore, there are only a few psychometrically sound instruments that measure self-stigma (28), and the construct is often intertwined with related constructs such as body image, body dissatisfaction, body shame, self-devaluation, and self-image. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to conduct an updated search specifically for self-stigma interventions with a broader definition of self-stigma to (1) provide a synopsis of existing interventions against self-stigma associated with visible chronic skin diseases, (2) evaluate their benefits and limitations, and (3) gather detailed information that can be used to improve or develop new programmes to reduce self-stigma in persons with visible chronic skin diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protocol and registration

Before the formal database search, the protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero, registration number: CRD42021284948). We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement in conducting and reporting the review (see Appendix S1).

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

The searched databases included PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and PsycINFO, without restriction by publication date. The search categories included self-stigma, skin diseases, and interventions. The category self-stigma included related constructs such as self-esteem, self-image, self-devaluation, and body image. The search strings for the 4 databases can be found in Appendix S1. Articles were eligible if they (a) were targeted at persons with a chronic visible skin disease listed in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Edition (ICD-11); (b) addressed an intervention aiming to reduce patients’ self-stigmatization; (c) were written in English or German; (d) were published in a peer-reviewed journal; and (e) if the full text was available.

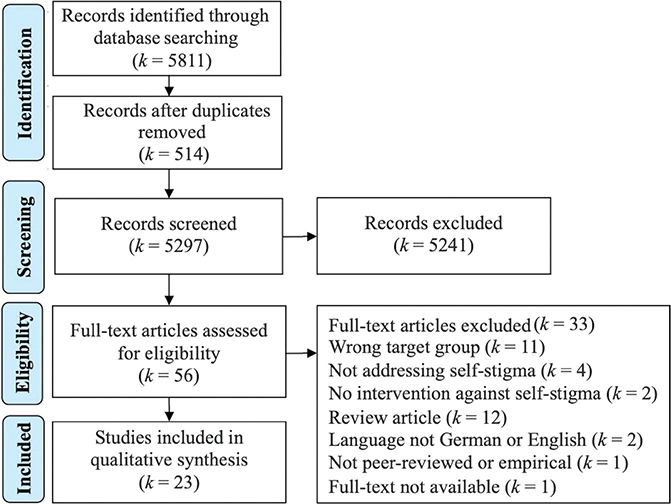

Preliminary searches were run by JT to establish the need for a systematic review of interventions against self-stigma in this population, and to construct the search and study selection processes. The definitive searches were conducted in October 2021 and re-run before the final analysis in April 2023. Additional records were identified through manual searches of the reference lists of relevant articles and of known relevant reviews. Fig. 1 shows a flowchart illustrating the article selection process.

Fig. 1. Flowchart illustrating article selection according to PRISMA guidelines (34).

First, 2 independent reviewers (all records were screened by JT, the second review was divided between HG/LW/MR) screened titles and abstracts of the 5,811 studies identified in the database search based on a list of specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. At this stage, 5,241 records were excluded because they were not relevant for the topic, were not conducted in a human population with a visible chronic skin disease, were duplicates, or were published in a language other than English or German. Reviewers had a fair agreement for title and abstract screening (Cohen’s kappa = 0.30). Discrepancies were resolved through a third reviewer (RS). Subsequently, the full text of studies considered as potentially relevant by at least 1 reviewer was retrieved and further assessed for eligibility by JT and RS. Reviewers had almost perfect agreement for full-text screening (Cohen’s kappa = 0.85). Any uncertainty regarding eligibility was resolved through discussion in the team. Another 33 records were excluded at this stage.

Data extraction and synthesis of results

Two independent reviewers (JT, RS) extracted data into a pre-defined extraction form in Covidence, a systematic review management tool (Veritas Health Innovation, VIC, Melbourne, Australia). Specifically, information on the study design, target population, sample size and characteristics, intervention (type and setting of intervention, duration of treatment, definition of control group), outcome measures, and reported effects of the intervention were extracted. Discrepancies were resolved through team consensus (JT, RS, CFZS). Final data were synthesized narratively.

Quality assessment and risk of bias within studies

All included studies were peer-reviewed. The first author (JT) assessed the methodological quality of included studies by means of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists (29), which are available for randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and qualitative studies, among others. For the risk of bias evaluation, quasi-experimental studies were treated as cohort studies. No individual risk of bias assessment was performed for studies that could not be assessed using any of the available CASP tools. The checklist consists of 10, 11, or 12 items for qualitative studies, RCTs, and cohort studies, respectively, which addressed both bias and quality of reporting.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 23 included studies are provided in Table I. Studies were published between 1996 and 2023; 11 were conducted in industrialized countries (30–33), 7 of which were set in the United Kingdom (34–40), and 12 in low- and middle-income countries (41–52). Study designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs, k = 7) (30, 34, 38, 40, 43, 45, 47), quasi-experimental studies (k = 4) (32, 44, 49, 51), cohort studies (k = 2) (31, 33), mixed-methods studies (k = 3) (37, 48, 52), qualitative studies (k = 5) (35, 36, 41, 42, 50), a cross-sectional study (46) and a case report study (39). Sample sizes varied considerably between studies, ranging from 2 to 1,684 participants (M = 164.56, SD = 341.90).

| Study characteristics | Participant information and sociodemographics | Intervention | Outcomes | ||||||

| Study ID | Study design | Country | n | Skin diagnosis | Type and setting | Duration and frequency | Control group(s) | Measure(s) and validation | Main finding(s) |

| Adkins (2022)(40) | RCT | UK | 451 | Any | Expand your Horizon writing exercise; online |

3 sessions of 15 min each, every 2 days | Sham control (creative writing exercise) | Body Appreciation Scale-2; Functionality Appreciation Scale; Appearance Anxiety Index; Skin Shame Scale (all validated) | Significant increase in body appreciation and functionality appreciation in the intervention but not control group from pre- to post-intervention and 1-month follow-up; no effects on appearance anxiety or skin-related shame |

| Arole (2002) (41) | Qualitative research | India | 24 | Leprosy | Integrated care approach at healthcare system level | Vertical approach (villages) | 2 open-ended questions | In the integrated approach, 85.7% (compared with 60% in the vertical approach) felt that leprosy was like any other disease and 78.6% (compared with 10% in the vertical approach) felt they could discuss their disease in public | |

| Augustine (2012) (42) | Qualitative research | India | 5 | Leprosy | Social skills training; group intervention | 10 full-day sessions over 3 weeks | none | Self-esteem was measured through (1) post-interviews (questions based on Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem scale and Bogardus Social Distancing Scale), (2) spontaneous remarks by patients during sessions, and (3) evaluation of the patients’ behaviour during practices or tasks at home | Improved self-perceptions, increase in confidence and hope |

| Bessell (2012) (34) | RCT | UK | 83 | Range of disfigurements | CBT; online | 8 sessions, 1x/week | (1) standard CBT-based face-to-face delivery, (2) no intervention | Body Image Quality of Life Inventory, Derriford Appearance Scale-24 (both validated) | Compared with the no inter-vention control group, FaceIT online had no effect on body image QoL but significantly reduced appearance concerns at 6-month follow-up (face-to-face intervention: significant increase in body image QoL at 6-month follow-up & significant reduction in appearance concerns 3- & 6-month follow-up) |

| Burr (1996) (35) | Qualitative research | UK | 14 | Psoriasis | Patient support group; group intervention | 1x/month; however, instead of attending meetings every month, members are using the support of the group when they feel they need it | None | Questionnaire not further specified | Support group meetings are described to be essential to the psychological well-being of individuals with skin complaints |

| Dadun (2017) (43) | RCT | Indonesia | 237 | Leprosy | CBT; counselling; socioeconomic development (to improve people‘s financial situation), “Contact”; single face-to-face; group intervention; contact events | 5 sessions | (1) ‘Contact – Counselling’ (8 sub-districts), (2) ‘Counselling – SED’ (7 sub-districts), (3) ‘SED – Contact’ (7 sub-districts) and (iv) ‘Control’ areas (8 sub-districts). | Stigma Assessment Reduction Impact (SARI) scale (newly adapted for population and/or language) | Significant reduction of inter-nalized stigma, disclosure concerns and anticipated stigma in the intervention areas from pre- to post-test; however, results of the control area were not reported. |

| Dellar (2022) (44) | NRES | Ethiopia | 251 | Leprosy, podoconiosis, lymphatic filariasis | Counselling; self-help; care package (health education, equipment; community workshops; single face-to-face; group intervention | Over 12 months | none | Adapted Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (newly adapted for population and/or language) | Significant decrease in inter-nalized stigma from baseline to 3- and 12-month follow-up |

| Edwards (2009) (30) | RCT | Australia | 67 | Ulceration | Lindsay Leg Club model of care, emphasizing socialization and peer support; community setting | 24 sessions, 1x/week | Traditional community nursing model consisting of individual home visits by a registered nurse | Rosenberg‘s Self Esteem Scale (validated) | Significant increase in self-esteem in intervention group compared with control group |

| Heidari (2023) (45) | RCT | Iran | 60 | Burns | Spiritual care programme; group intervention | 8 sessions of 1 h each over the course of 2 weeks | Routine Care | Beck’s Self‑Concept Test (validated) | Significant improvement in body image (BSCT) in the intervention but not the control group from baseline to post-test and 3-month follow-up |

| Iliffe (2019) (36) | Qualitative research | UK | 12 | Alopecia areata | Self-help; online (Facebook peer support group) | None | Participants describe the forum as valuable for coping, normalization of the condition, and sharing experiences, which appears to help in reducing shame and stigma | ||

| Jay (2021) (46) | Cross- sectional study |

Nepal | 98 | Leprosy | Self-help; group intervention | None | Stigma Assessment Reduction Impact scale (validated) | Access to multiple groups significantly predicted less internalized stigma (self-help group identification was indirectly linked to decreased stigma) | |

| Jolly (2014)(31) | Cohort study | United States | 15 | Lupus erythematosus | CBT; education, cosmetic training, mindfulness; group intervention | 10 sessions of 120 min each, 1x/week | Usual care | Body Image in Lupus Scale (validated) | Improved body image at post-intervention and 2nd follow-up (14 weeks post-intervention) |

| Krasuska (2018)(37) | Mixed methods |

UK | 5 | HS; vitiligo; rosacea | Self-help; online | Self-paced but at least 1x/week | None | Overt Aggression Scale, Forms of Self-Criticising/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale (all validated) | Evidence was mixed. Two participants report decreased shame after the intervention, while 2 others experienced increased shame; similarly, only 2 participants experienced lower self-criticism after the intervention |

| Latifi (2020) (47) | RCT | Iran | 34 | Skin cancer | Self-healing training | 12 sessions of 90 min each | No intervention | Body Image Concern Inventory (validated) |

Significant decrease in body image concern in intervention group compared with control group |

| Lusli (2016) (48) | Mixed methods |

Indonesia | 124 | Leprosy | Counselling; single face-to-face; group intervention; family counselling | 5 sessions of 30–60 min each | No intervention | Stigma Assessment Reduction Impact scale (validation status unclear) |

SSS total reduced from 21.55 to 12.00 (p-value <0.001) in the intervention group, which is a significantly larger reduction compared with the control group Internalized stigma,: mean difference: -3-43 (0.51), <0.001 |

| Ng (2007) (32) | NRES | Hong Kong | 76 | Lupus erythematosus | Psychosocial group training | 6 sessions of 2.5 h each, 1x/week | No intervention | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (validated) | Significant increase in self-esteem in intervention group compared with control group |

| Ozdemir (2019) (49) | NRES | Turkey | 110 | Burns | Yoga nidra; single face-to-face | 12 sessions of 30 min each, 3x/week | No intervention | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Body Image Scale (both newly adapted for population and/or language) | Significant increase in self-esteem in the experimental group compared with the control group |

| Papadopoulos (1999) (38) | Randomized controlled trial | UK | 16 | Vitiligo | CBT; single face-to-face | 8 sessions of 1 h each, 1x/week | Treatment as usual | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Situational Inven-tory of Body Image Dysphoria, Body Image Automatic Thoughts Question-naire (all validated) | Significant improvement in self-esteem, body image dysphoria, and body image automatic thoughts in intervention group compared with control group |

| Peters (2016) (50) | Qualitative research | Indonesia | 12 | Leprosy | Participatory video; group intervention | 12 & 22 sessions, between 1 hand a full day | None | Participants reported having a good time, a greater sense of togetherness, increased self-esteem, individual agency, and willingness to take action in the community | |

| Seyedoshohadaee (2019) (51) | NRES | Iran | 130 | Burns | Educational training; group intervention | 3 sessions of 2 h each | None | Satisfaction with Appearance Scale(validated) | Significant decrease in body image dissatisfaction from pre- to post-test |

| Szepietowski (2008) (33) | Prospective (baseline and after treatment) | Poland | 1684 | Onychomycosis | Medical treatment: combined therapy with terbinafine and amorolfine | 6 months | None | Six-Item Stigmatisation Scale(validated) | Significant reduction of stig-matisation (p<0.001) to about 40% of the baseline level; the mean stigmatisation level after the completion of the study was 2.1±2.6 points (range 0–14 points) vs 5.7±3.8 points (range 0–17 points) before treatment. The comparison of answers to individual questions before and after the treatment revealed that in every item, 55–67% reduction of the baseline scoring was observed. The difference for every comparison was highly significant (p<0.001) |

| Van‘t Noordende (2021) (52) | Mixedmethods | Ethiopia | 275 | Leprosy, podoconiosis; lymphatic filariasis | Family-based inter-vention: self-manage-ment of dis-abilities, awareness raising, socioeconomic em-powerment; group intervention | 8 monthly sessions | None | Stigma Assessment Reduction Impact scale (newly adapted for population and/or language) | Significant reduction in stigma (including internalized stigma) from baseline to follow-up |

| Wittkowski (2007) (39) | Case report | UK | 2 | Dermatitis/eczema | CBT; single face-to-face | 8 sessions of 1 h each, 1x/week or 1x/2 weeks | None | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (validated), VAS (author-created items) | No effect on self-esteem; decrease in perceived stigma (VAS scale, not validated) |

| CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; HS: hidradenitis suppurativa; NRES: non-randomized experimental study; QoL: quality of life; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale. | |||||||||

The studies examined the effects of self-stigma interventions in a range of skin conditions: 6 programmes were designed for persons with leprosy (41–43, 46, 48, 50), 3 in persons with burns (45, 49, 51) and 2 in persons with lupus erythematosus (31, 32), while 1 study each addressed alopecia areata (36), atopic dermatitis (39), onychomycosis (33), psoriasis (35), skin cancer (47), ulceration (30), and vitiligo (38). Five studies targeted a range of skin conditions and disfigurements (34, 37, 40, 44, 52).

Intervention characteristics

The studies examined a variety of interventions: 3 studies used cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) (34, 38, 39), 4r offered self-help/self-healing (36, 37, 46, 47), 2 administered social skills training (32, 42), and 1 study each investigated counselling (48), educational training (51), creation of a participatory video (50), a patient support group (35), a family-based intervention (52) a body-functionality writing exercise (40), yoga nidra (49), a spiritual care programme (45), and medical treatment (33). Furthermore, 3 studies offered combinations of several of these intervention approaches (31, 43, 44). Two studies evaluated novel treatment approaches at the level of the community or healthcare system, namely the Lindsay Leg Club model of care (30) and an integrated care approach (41), both of which aimed to improve their patients’ self-esteem through reducing isolation and facilitating social and peer support. Of the other interventions, most were delivered as group interventions (k = 9) (31, 32, 35, 42, 45, 46, 50–52) but also face-to-face (k = 3) (38, 39, 49), as a combination of these (k = 3) (43, 44, 48), or online (k = 4) (34, 36, 37, 40). The number of intervention sessions ranged from 3 to 24 sessions (M = 9.19, SD = 5.33) with an average duration of 75 min (SD = 43.59, range: 15–150 min) per session, except for 2 interventions that comprised (occasional) full-day sessions. In the study by Szepietowski and Reich (33), medical treatment with a combination of oral terbinafine and topical amorolfine was administered daily for 6 months.

Effectiveness of interventions

All of the 17 quantitative studies reported improvements in self-stigma and related constructs. Importantly, 7 of these studies did not include a control group and 2 studies did not report the results for the control group, which does not allow to be ruled out that observed changes were due to the passage of time. However, where results of a control group were included (waitlist [32, 47, 49]; treatment as usual [30, 38, 45]), these improvements were comparatively larger in the intervention group. Only one study (48) did not find a significant difference between the counselling group and a waitlist-control group: both groups showed an equally large reduction in internalized stigma as measured with the Sari Stigma Scale (53).

Furthermore, 4 studies reported mixed effects: first, upon participating in an online self-help intervention by Krasuska et al. (37), 2 out of 5 participants experienced decreased levels of shame, while 2 others felt more shame and similar results were found for self-criticism. Second, the online CBT intervention FaceIT by Bessell et al. (34) had no significant effect on body image QoL but did reduce appearance concerns at 6-month follow-up compared with a waitlist control group. The face-to-face version of FaceIT produced slightly larger effects on both body image QoL and appearance concerns, and the latter effect already became apparent at 3-month follow-up, although the authors did not report whether these differences between face-to-face and online delivery of the programme were significant. Third, in comparison with a creative writing exercise, the Expand Your Horizon writing exercise administered by Adkins et al. (40) led to a significant increase in both body appreciation and functionality appreciation from pre- to post-intervention and 1-month follow-up, with medium-to-large effects. However, no effects were found on appearance anxiety or skin-related shame. Lastly, while a patient with eczema receiving face-to-face CBT in the case report by Wittkowski & Richards (39) did not experience an improvement in self-esteem, a decrease in self-stigma was noted. Given that most studies did not report effect sizes, their effectiveness cannot be formally compared.

In all 5 qualitative studies, participants reported positive effects of the respective interventions: an integrated care approach implemented in several Indian communities helped people with leprosy feel their illness was like any other disease and they could discuss it in public, and more so compared with patients being treated in communities with the traditional care approach (41). Furthermore, patients with leprosy had improved self-perceptions and increased confidence and hope after taking part in group social skills training (42) and increased self-esteem, agency, and sense of togetherness upon creating a participatory video (50). Similarly, patient support groups, both in person (35) and online (36), were valued by patients with psoriasis and alopecia areata, respectively. Specifically, the investigation of an online platform by Illife and Thompson (36) showed that patients perceived it to be helpful in normalizing the condition and reducing stigma and shame. Again, apart from the study by Arole et al. (41), none of these studies had a control group, and their qualitative nature limits the conclusions that can be drawn concerning self-stigma and related constructs.

Other benefits and limitations of the different interventions are presented in Table II. In addition to their effectiveness, we evaluated programmes on duration, cost, accessibility, and promoting opportunity for social connection and support. Some programmes were particularly short (≤ 6 hours) and easy to implement in users’ daily lives (40, 51), while others took more than 15 hours to complete, with some lasting several half- or even full days. Such intensive programmes may be beneficial in specific situations (e.g., if participants’ journey is too long to be made repeatedly for shorter but more frequent sessions) but are not feasible for many potential users. Furthermore, programmes that were able to keep costs at a minimum for patients and insurance providers were viewed more favourably (34–37, 40, 46, 49, 52). In addition, some programmes were independent of location or local healthcare infrastructure and particularly accessible: they did not require healthcare professionals to deliver the intervention but adopted a train-the-trainer approach instead (49), or relied on self-help (37) and online approaches (34, 36, 40), which may make them advantageous for patients living in remote locations or those with otherwise low mobility. At the same time, a disadvantage is that online interventions require a degree of technical ability and might not be the preferred medium for all. Importantly, all of these factors contribute to the scalability of these interventions: some of the low-cost, easily accessible solutions likely have the greatest potential to be adapted for other languages and cultures, and implemented in new settings. Notably, we consider it an additional benefit that some programmes facilitated exchange among patients (30–32, 35, 36, 42, 44–46, 48), which many patients highly value (54), or succeeded in tackling public stigma in addition to self-stigma (41, 43, 44).

| Study ID | Benefits | Limitations | Other | ||||||

| Short duration | Low/no cost | Independent of location | Connects patients | Reduction of social stigma | Long duration | Expensive | Requires technical capacities | ||

| Adkins (2022) (40) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Arole (2002) (41) | X | – Change at healthcare level difficult to implement | |||||||

| Augustine (2012) (42) | X | X | |||||||

| Bessell (2012) (34) | X | X | X | ||||||

| Burr (1996) (35) | X | X | |||||||

| Dadun (2017) (43) | X | For implementation | + Combines different approaches, intervenes at different levels | ||||||

| Dellar (2022) (44) | X | X | X | ||||||

| Edwards (2009) (30) | X | ||||||||

| Heidari (2023) (45) | X | ||||||||

| Iliffe (2019) (36) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Jay (2021) (46) | X | X | |||||||

| Jolly (2014) (31) | X | X | |||||||

| Krasuska (2018) (37) | X | X | |||||||

| Latifi (2020) (47) | |||||||||

| Lusli (2016) (48) | X | X | + Combines different approaches, intervenes at different levels | ||||||

| Ng (2007) (32) | X | X | |||||||

| Ozdemir (2019) (49) | X | X | |||||||

| Papadopoulos (1999) (38) | |||||||||

| Peters (2016) (50) | X | ||||||||

| Seyedoshohadaee (2019) (51) | |||||||||

| Szepietowski (2008) (33) | X | + Treats physical symptoms of onychomycosis | |||||||

| Van’t Noordende (2021) (52) | + Improves self-care of illness | ||||||||

| Wittkowski (2007) (39) | |||||||||

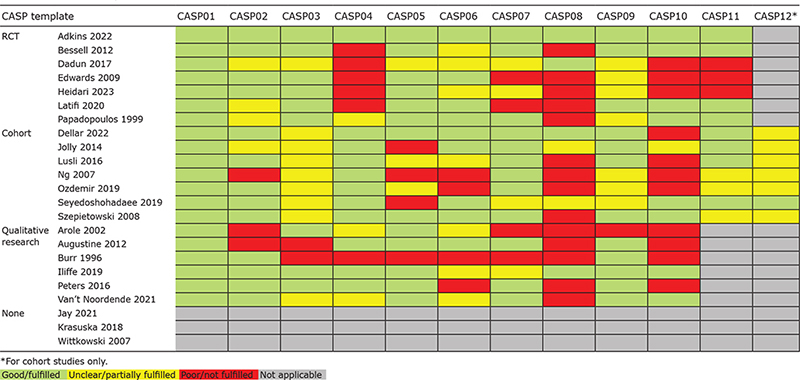

Risk of bias assessment

The study designs and quality were heterogeneous (see Table III). Overall, in many studies, reporting of methodology was unclear or poor. More specifically, some RCTs lacked a description of the randomization procedure, and blinding was mostly not possible. Many cohort studies did not adequately consider confounding factors and reported short-term or incomplete follow-up. Most qualitative studies did not consider the relationship between researcher and participants and data analysis was poorly described. Additionally, irrespective of the study design, results often lacked confidence intervals and effect sizes or were not thoroughly presented. For 3 studies, none of the available CASP templates was applicable so the quality of these studies could not be formally assessed.

|

The generalizability of findings to our target population is limited for most studies but this may differ depending on the goal and target population and needs to be considered by the reader on a case-to-case basis.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review aimed to identify self-stigma reduction interventions for individuals with a visible chronic skin disease and to evaluate their effectiveness and limitations. Twenty-three studies assessing such interventions were retrieved, the majority of which reported positive effects on self-stigma and related variables. In this updated literature search, we identified 15 new studies that had not been reported by Topp et al. (26). This reflects the increased attention to self-stigma (9 new publications since 2019) but also the refined definition of self-stigma used in the present review. However, mirroring the findings by Topp et al. (26), heterogeneity in study designs and poor study quality did not allow for a formal analysis of their effectiveness.

It is striking that programmes are available for only a few countries, mostly located in Southeast Asia and Europe. Moreover, self-stigma interventions for persons with leprosy are comparatively well researched, whereas there is a clear lack of evidence-based interventions for non-communicable skin conditions. Cultural differences and disease-specific characteristics limit the transferability of these programmes to other contexts, i.e., other countries, cultures, and skin diseases. Nevertheless, these studies provide relevant information for the development of new interventions in terms of content and structure: CBT approaches have been very thoroughly tested, and most face-to-face interventions consisted of 8–10 sessions with a duration of 1–1.5 hours per session. So far, only a few online programmes are available.

The interventions and their effects identified in this review are comparable to those found to be effective against self-stigma in other health domains. For persons with HIV, Ma et al. (55) concluded that psychotherapy interventions, narrative interventions, and community participation interventions are particularly helpful, while psychoeducation produced mixed effects. Paralleling the interventions against leprosy-related self-stigma, Pantelic et al. (56) found social empowerment, economic strengthening, and CBT to be most effective in HIV. Similarly, CBT has positive effects on mental illness-related (57, 58) and weight self-stigma (59).

Importantly, other approaches that have not yet been examined in relation to self-stigma in dermatology were shown to be effective in reducing weight self-stigma: first, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) led to significantly larger reductions in self-stigma compared with a waitlist control group (60–62). Second, initial promising evidence exists for self-compassion interventions targeting weight self-stigma (63–65). Also, a combined intervention consisting of acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness approaches delivered in a group format was shown to reduce weight self-stigma, self-criticism, and shame in women with overweight and obesity with changes being maintained at 3-month follow-up (66). These approaches may hold promise in the context of dermatological self-stigma and warrant investigation.

Overall, the quality of studies included in the present review ranged from moderate to poor. Ten studies were based on samples of 50 participants or fewer and the majority of quantitative studies included fewer than 100 patients, raising concerns about the power of the reported analyses. RCTs were almost exclusively used for CBT-based interventions. Consequently, the evidence for other approaches is weak. Furthermore, in some of the included studies, measurement instruments assessing self-stigma and related constructs were used that were not yet validated in the studied population and/or language. Additional caution needs to be paid when interpreting the study results, as most studies did not include a control group or a follow-up, so it is unclear whether the positive effects can be attributed to the intervention rather than time effects or other confounding factors and whether they are stable over longer periods.

Limitations

Due to the poor study quality and heterogeneous study designs, a meta-analytic approach was not possible, hence this systematic review is limited to a narrative synthesis. Second, the literature search was limited to work published in English or German and may, consequently, have overlooked relevant publications in other languages. Third, the assessment of study quality was conducted using CASP templates. As these are available for a selected few study designs, the quality of 3 studies could not be assessed in this review. Lastly, it was not possible to adequately assess publication bias and reporting bias, due to the heterogeneity in study designs and due to the lack of preregistrations and publication of study protocols.

Future directions

Two key directions for research need to be pointed out. First, thoroughly conducted and well-powered randomized-controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of existing interventions against self-stigma are urgently needed. Only RCTs can provide reliable evidence on the effects that can be attributed to the intervention. In addition, these studies should include follow-up assessments to determine whether potential positive effects persist over time. Second, evidence-based interventions need to be developed or adapted into different languages, for different cultures and different skin conditions. For example, patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), which has a tremendous psychosocial impact on patients and often evokes feelings of shame and a negative body image, might benefit greatly from a self-stigma reduction intervention. Consequently, disease-specific programmes that target the particular needs and challenges of HS and other skin conditions that have not been addressed in this context would be valuable tools in the psychodermatological support for those affected. Importantly, skin-generic interventions that are designed to be inclusive for a broad range of skin diseases or visible differences in general could prove to be even more cost-effective. Researchers and clinicians aiming to design such interventions may build on the existing interventions presented here but may also take inspiration from the mental health and weight-related self-stigma literature. Specifically, the current evidence for reducing skin disease-related self-stigma is most robust for traditional CBT; however, third-wave CBT approaches including ACT, mindfulness, or self-compassion interventions also show considerable promise.

Based on the results of this review, a high frequency of sessions (≥ 1 session/week) of moderate length (1–1.5 h) is well supported. While more intensive interventions, such as half- or full-day sessions, may be beneficial in certain situations, their scalability remains challenging. Importantly, as supported by findings from another systematic review (67), the length and number of sessions do not appear to be critical predictors of intervention success. Therefore, emphasis should be placed on the quality of the content and its feasibility. To enhance the implementation and scalability of future self-stigma interventions, it is recommended that these interventions be skin-generic and utilize online platforms or a train-the-trainer model.

It needs to be noted that it should not be the sole responsibility of persons with a visible difference to tackle and cope with (self-)stigma. Hence, interventions to reduce stigma in the general public and particularly in certain groups who are in frequent contact with dermatology patients, such as medical staff and teachers, are central in alleviating the burden of living with a visible chronic skin disease. Therefore, research into and implementation of anti-stigma programmes need to be driven forward. Nevertheless, psychosocial interventions for patients offer a more immediate improvement in quality of life and well-being.

Conclusion

This review identified multiple interventions aiming to reduce self-stigma in people with chronic skin diseases, all of which were shown to have at least some positive effects on self-stigma and related constructs. Importantly, availability is limited to a few countries, languages, and skin conditions. Moreover, as many interventions were evaluated in studies of suboptimal quality, results regarding their effectiveness need to be interpreted with caution. In conclusion, efforts to develop, evaluate, and implement interventions tackling skin disease-related self-stigma are needed in order to improve patients’ psychosocial well-being.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Scientific Communication Team of the IVDP, especially Amber Hönning and Sara Tiedemann, for copy-editing the article. They acknowledge financial support from the Open Access Publication Fund of UKE – Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf and DFG – German Research Foundation.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Schaefer I, Rustenbach SJ, Zimmer L, Augustin M. Prevalence of skin diseases in a cohort of 48,665 employees in Germany. Dermatology 2008; 217: 169–172. https://doi.org/10.1159/000136656

- Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Wiśnicka B. Itching in patients suffering from psoriasis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2002; 10: 221–226.

- Verhoeven EWM, Kraaimaat FW, van de Kerkhof PCM, van Weel C, Duller P, van der Valk PGM, et al. Prevalence of physical symptoms of itch, pain and fatigue in patients with skin diseases in general practice. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 1346–1349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07916.x

- Yosipovitch G, Goon ATJ, Wee J, Chan YH, Zucker I, Goh CL. Itch characteristics in Chinese patients with atopic dermatitis using a new questionnaire for the assessment of pruritus. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41: 212–216. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01460.x

- Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, Lien L, Poot F, Jemec GBE, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 984–991. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.530

- Guo F, Yu Q, Liu Z, Zhang C, Li P, Xu Y, et al. Evaluation of life quality, anxiety, and depression in patients with skin diseases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99: e22983. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022983

- Troisi A, Nanni RC, Giunta A, Manfreda V, Del Duca E, Criscuolo S, et al. Cutaneous body image in psoriasis: the role of attachment style and alexithymia. Curr Psychol 2023; 42: 7693–7700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02032-8

- Yew YW, Kuan AHY, Ge L, Yap CW, Heng BH. Psychosocial impact of skin diseases: a population-based study. PLoS ONE 2020; 15: e0244765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244765

- Basra MKA, Shahrukh M. Burden of skin diseases. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2009; 9: 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1586/erp.09.23

- Feldman SR, Malakouti M, Koo JYM. Social impact of the burden of psoriasis: effects on patients and practice. Dermatol Online J 2014; 20:13030/qt48r4w8h2. https://doi.org/10.5070/D3208023523

- Stülpnagel CC von, Augustin M, Düpmann L, da Silva N, Sommer R. Mapping risk factors for cumulative life course impairment in patients with chronic skin diseases: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: 2166–2184. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17348

- Corrigan PW, Rao D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can J Psychiatry 2012; 57: 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700804

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychol 2006; 25: 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875

- Park K, MinHwa L, Seo M. The impact of self-stigma on self-esteem among persons with different mental disorders. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2019; 65: 558–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019867352

- Werner P, Aviv A, Barak Y. Self-stigma, self-esteem and age in persons with schizophrenia. Int Psychogeriatr 2008; 20: 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610207005340

- Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. Stigmatisation, avoidance behaviour and difficulties in coping are common among adult patients with vitiligo. Acta Derm Venereol 2015; 95: 553–558. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1981

- Barisone M, Bagnasco A, Hayter M, Rossi S, Aleo G, Zanini M, et al. Dermatological diseases, sexuality and intimate relationships: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J Clin Nurs 2020; 29: 3136–3153. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15375

- Augustin M, Zschocke I, Wiek K, Bergmann A, Peschen M, Schöpf E, et al. Krankheitsbewältigung und Lebensqualität bei Patienten mit Feuermalen unter Laser-Therapie. Hautarzt 1998; 49: 714–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001050050814

- Temel AB, Bozkurt S, Alpsoy E. 029 Internalized stigma in acne vulgaris, vitiligo and alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: S197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.125

- Sommer R, Augustin M, Mrowietz U, Topp J, Schäfer I, Spreckelsen R von. Stigmatisierungserleben bei Psoriasis – qualitative Analyse aus Sicht von Betroffenen, Angehörigen und Versorgern. Hautarzt 2019; 70: 520–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00105-019-4411-y

- Nobre N, Pereira M, Roine RP, Sutinen J, Sintonen H. HIV-related self-stigma and health-related quality of life of people living with HIV in Finland. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2018; 29: 254–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2017.08.006

- Corrigan PW, Sokol KA, Rüsch N. The impact of self-stigma and mutual help programs on the quality of life of people with serious mental illnesses. Community Ment Health J 2013; 49: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-011-9445-2

- Mosanya TJ, Adelufosi AO, Adebowale OT, Ogunwale A, Adebayo OK. Self-stigma, quality of life and schizophrenia: an outpatient clinic survey in Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2014; 60: 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764013491738

- Tang I-C, Wu H-C. Quality of life and self-stigma in individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q 2012; 83: 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-012-9218-2

- Palmeira L, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cunha M. The role of weight self-stigma on the quality of life of women with overweight and obesity: a multi-group comparison between binge eaters and non–binge eaters. Appetite 2016; 105: 782–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.015

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, Schäfer I, Sommer R, Mrowietz U, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 2029–2038. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.15734

- World Health Organization. Global report on psoriasis; 2016 [cited 2023 Dec 6]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/204417/9789241565189_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Luck-Sikorski C, Roßmann P, Topp J, Augustin M, Sommer R, Weinberger NA. Assessment of stigma related to visible skin diseases: a systematic review and evaluation of patient-reported outcome measures. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 499–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17833

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklists; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 6]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- Edwards H, Courtney M, Finlayson K, Shuter P, Lindsay E. A randomised controlled trial of a community nursing intervention: improved quality of life and healing for clients with chronic leg ulcers. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 1541–1549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02648.x

- Jolly M, Peters KF, Mikolaitis R, Evans-Raoul K, Block JA. Body image intervention to improve health outcomes in lupus: a pilot study. J Clin Rheumatol 2014; 20: 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000000141

- Ng P, Chan W. Group psychosocial program for enhancing psychological well-being of people with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil 2007; 6: 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1300/J198v06n03_05

- Szepietowski JC, Reich A. Stigmatisation in onychomycosis patients: a population-based study. Mycoses 2009; 52: 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01618.x

- Bessell A, Brough V, Clarke A, Harcourt D, Moss TP, Rumsey N. Evaluation of the effectiveness of Face IT, a computer-based psychosocial intervention for disfigurement-related distress. Psychol Health Med 2012; 17: 565–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2011.647701

- Burr S, Gradwell C. The psychosocial effects of skin diseases: need for support groups. Br J Nurs 1996; 5: 1177–1182. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.1996.5.19.1177

- Iliffe LL, Thompson AR. Investigating the beneficial experiences of online peer support for those affected by alopecia: an interpretative phenomenological analysis using online interviews. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181: 992–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17998

- Krasuska M, Millings A, Lavda AC, Thompson AR. Compassion-focused self-help for skin conditions in individuals with insecure attachment: a pilot evaluation of acceptability and potential effectiveness. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: e122–e123. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15934

- Papadopoulos L, Bor R, Legg C. Coping with the disfiguring effects of vitiligo: a preliminary investigation into the effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy. Br J Med Psychol 1999; 72: 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711299160077

- Wittkowski A, Richards HL. How beneficial is cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of atopic dermatitis? A single-case study. Psychol Health Med 2007; 12: 445–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500601109268

- Adkins KV, Overton PG, Thompson AR. A brief online writing intervention improves positive body image in adults living with dermatological conditions. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022; 9: 1064012. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1064012

- Arole S, Premkumar R, Arole R, Maury M, Saunderson P. Social stigma: a comparative qualitative study of integrated and vertical care approaches to leprosy. Lepr Rev 2002; 73: 186–196. https://doi.org/10.47276/lr.73.2.186

- Augustine V, Longmore M, Ebenezer M, Richard J. Effectiveness of social skills training for reduction of self-perceived stigma in leprosy patients in rural India: a preliminary study. Lepr Rev 2012; 83: 80–92. https://doi.org/10.47276/lr.83.1.80

- Dadun D, van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, Lusli M, Zweekhorst MBM, Bunders JGF, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia: a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev 2017; 88: 2–22. https://doi.org/10.47276/lr.88.1.2

- Dellar R, Ali O, Kinfe M, Mengiste A, Davey G, Bremner S, et al. Effect of a community-based holistic care package on physical and psychosocial outcomes in people with lower limb disorder caused by lymphatic filariasis, podoconiosis, and leprosy in Ethiopia: results from the EnDPoINT pilot cohort study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2022; 107: 624–631. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-1180

- Heidari M, Gheshlaghi AN, Masoudi R, Raeisi H, Sobouti B. Effects of a spiritual care program on body image and resilience in patients with second-degree burns in Iran. J Relig Health 2024; 63: 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01732-0

- Jay S, Winterburn M, Choudhary R, Jha K, Sah AK, O’Connell BH, et al. From social curse to social cure: a self-help group community intervention for people affected by leprosy in Nepal. Community Appl Soc Psychol 2021; 31: 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2510

- Latifi Z, Soltani M, Mousavi S. Evaluation of the effectiveness of self-healing training on self-compassion, body image concern, and recovery process in patients with skin cancer. Complement Ther Cin Pract 2020; 40: 101180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101180

- Lusli M, Peters R, van Brakel W, Zweekhorst M, Iancu S, Bunders J, et al. The impact of a rights-based counselling intervention to reduce stigma in people affected by leprosy in Indonesia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016; 10: e0005088. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005088

- Ozdemir A, Saritas S. Effect of yoga nidra on the self-esteem and body image of burn patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2019; 35: 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.02.002

- Peters RMH, Zweekhorst MBM, van Brakel WH, Bunders JFG, Irwanto. ‘People like me don’t make things like that’: participatory video as a method for reducing leprosy-related stigma. Glob Public Health 2016; 11: 666–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1153122

- Seyedoshohadaee M, Khachian A, Seyedfatemi N, Mahmoudi M. The effect of short-term training course by nurses on body image in patients with burn injuries. World J Plast Surg 2019; 8: 359–364.

- Van’t Noordende AT, Wubie Aycheh M, Tadesse T, Hagens T, Haverkort E, Schippers AP. A family-based intervention for prevention and self-management of disabilities due to leprosy, podoconiosis and lymphatic filariasis in Ethiopia: a proof of concept study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2021; 15: e0009167. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009167

- Dadun, Peters RM, van Brakel WH, Lusli M, Damayanti R, Bunders JF, et al. Cultural validation of a new instrument to measure leprosy-related stigma: the SARI Stigma Scale. Lepr Rev 2017; 88: 23–42. https://doi.org/10.47276/lr.88.1.23

- Schick TS, Höllerl L, Biedermann T, Zink A, Ziehfreund S. Impact of digital media on the patient journey and patient-physician relationship among dermatologists and adult patients with skin diseases: qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e44129. https://doi.org/10.2196/44129

- Ma PHX, Chan ZCY, Loke AY. Self-stigma reduction interventions for people living with HIV/AIDS and their families: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 2019; 23: 707–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2304-1

- Pantelic M, Steinert JI, Park J, Mellors S, Murau F. ‘Management of a spoiled identity’: systematic review of interventions to address self-stigma among people living with and affected by HIV. BMJ Glob Health 2019; 4: e001285. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001285

- Lucksted A, Drapalski A, Calmes C, Forbes C, DeForge B, Boyd J. Ending self-stigma: pilot evaluation of a new intervention to reduce internalized stigma among people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2011; 35: 51–54. https://doi.org/10.2975/35.1.2011.51.54

- Fung KMT, Tsang HWH, Cheung W. Randomized controlled trial of the self-stigma reduction program among individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2011; 189: 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.02.013

- Pearl RL, Wadden TA, Bach C, Gruber K, Leonard S, Walsh OA, et al. Effects of a cognitive-behavioral intervention targeting weight stigma: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2020; 88: 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000480

- Lillis J, Hayes SC, Bunting K, Masuda A. Teaching acceptance and mindfulness to improve the lives of the obese: a preliminary test of a theoretical model. Ann Behav Med 2009; 37: 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9083-x

- Palmeira L, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cunha M. Exploring the efficacy of an acceptance, mindfulness & compassionate-based group intervention for women struggling with their weight (Kg-Free): a randomized controlled trial. Appetite 2017; 112: 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.027

- Potts S, Krafft J, Levin ME. A pilot randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy guided self-help for overweight and obese adults high in weight self-stigma. Behav Modif 2022; 46: 178–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445520975112

- Braun TD, Olson K, Panza E, Lillis J, Schumacher L, Abrantes AM, et al. Internalized weight stigma in women with class III obesity: a randomized controlled trial of a virtual lifestyle modification intervention followed by a mindful self-compassion intervention. Obes Sci Pract 2022; 8: 816–827. https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.616

- Hopkins CM. Reduction of internalized weight bias via mindful self-compassion: theoretical framework and results from a randomized controlled trial [Doctoral dissertation]. Durham, NC: Duke University, 2022.

- Forbes YN, Moffitt RL, van Bokkel M, Donovan CL. Unburdening the weight of stigma: findings from a compassion-focused group program for women with overweight and obesity. J Cogn Psychother 2020; 34: 336–357. https://doi.org/10.1891/JCPSY-D-20-00015

- Palmeira L, Cunha M, Pinto-Gouveia J. Processes of change in quality of life, weight self-stigma, body mass index and emotional eating after an acceptance-, mindfulness- and compassion-based group intervention (Kg-Free) for women with overweight and obesity. J Health Psychol 2019; 24: 1056–1069. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316686668

- Hou S-I, Charlery S-AR, Roberson K. Systematic literature review of Internet interventions across health behaviors. Health Psychol Behav Med 2014; 2: 455–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2014.895368