ORIGINAL REPORT

Psychiatric Comorbidities of Childhood-onset Atopic Dermatitis in Relation to Eczema Severity: A Register-based Study among 28,000 Subjects in Finland

Amanda BLANCO SEQUEIROS1, Suvi-Päivikki SINIKUMPU2, Jari JOKELAINEN3 and Laura HUILAJA2

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Oulu, 2Department of Dermatology, University Hospital of Oulu, Oulu, and Medical Research Center, Research Unit of Clinical Medicine, University of Oulu, Oulu, and 3Northern Finland Birth Cohorts, Arctic Biobank, Infrastructure for Population Studies, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

Data on the severity of childhood-onset atopic dermatitis (AD) in relation to psychiatric comorbidities is scarce, even though AD predisposes to psychiatric comorbidities and the commonness of childhood-onset AD and its significance in disease progression are recognized. The purpose of this nationwide, register-based study of child patients diagnosed with AD in Finland between 1987 and 2017 was to determine how psychiatric comorbidities of AD patients differ depending on the disease severity of childhood-onset AD. AD severity was assessed by purchased AD treatment. Medications purchased after the first recorded AD diagnosis were included in the subgrouping “Risk of psychiatric comorbidities”, which was analysed by the ages of 18 and 30 years. The main finding of this study is that risk of several psychiatric disorders, i.e., depression, anxiety disorders, panic disorder, and bipolar disorder, is increased by the AD severity in childhood-onset AD at a young age. No difference was found for behavioural disorders, including hyperkinetic disorder, depending on AD severity. Childhood-onset AD is associated with different psychiatric comorbidities depending on AD severity, which supports the importance of mental health evaluation in AD patients.

Key words: atopic dermatitis; disease severity; childhood-onset AD.

SIGNIFICANCE

Atopic dermatitis is one of the most common skin diseases, affecting both children and adults. It varies by clinical morphology, disease severity, and course. Many comorbidities, including psychiatric, are associated with atopic dermatitis. Since not much is known about the association between childhood-onset atopic dermatitis severity and psychiatric comorbidity, we performed a nationwide registry study in Finland. We found that childhood-onset atopic dermatitis is already associated with different psychiatric comorbidities at young age depending on atopic dermatitis severity, which supports the importance of mental health evaluation in atopic dermatitis patients.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2024; 104: adv40790. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v104.40790.

Copyright: © 2024 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

Submitted: May 14, 2024; Accepted after revision: Oct 22, 2024; Published: Nov 13, 2024

Corr: Laura Huilaja, Department of Dermatology, Oulu University Hospital, P.B. 20, FIN-90029 Oulu, Finland. E-mail: laura.huilaja@oulu.fi

Competing interests and funding: LH has received educational grants from Takeda, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, AbbVie, and LEO Pharma, honoraria from Sanofi Genzyme, Novartis, Abbvie, LeoPharma, and OrionPharma for consulting and/or speaking, and is an investigator for Abbvie and Amgen. S-PS has received honoraria from LEOPharma and Sanofi Genzyme for speaking and is an investigator for Abbvie and Amgen. JJ and ABS declare no conflict of interest.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease varying in clinical morphology, disease severity, and course (1). AD is associated with several comorbidities, which are not only limited to atopic conditions (1–3). The association between AD and psychiatric comorbidity is well demonstrated in adults (4). Similarly, AD’s comorbidity burden is shown to increase with AD severity (5–9). However, fewer data exist on childhood-onset AD specifically in relation to psychiatric conditions (9) and AD severity (6, 7), despite the fact that AD onset is primarily described in early childhood (10) and an earlier age at onset predicts greater AD severity (11). The objective of this study was to determine how the risk of psychiatric comorbidities of AD patients differs depending on the disease severity of childhood-onset AD.

METHODS

This was a nationwide, registry-based study of cases diagnosed with AD in childhood in Finland between 1996 and 2017. The research material consists of patient health record data obtained from the Finnish Health Register for Health Care (CRHC), a database maintained by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. CRHC includes data from all Finnish hospitals on both in- and outpatient visits.

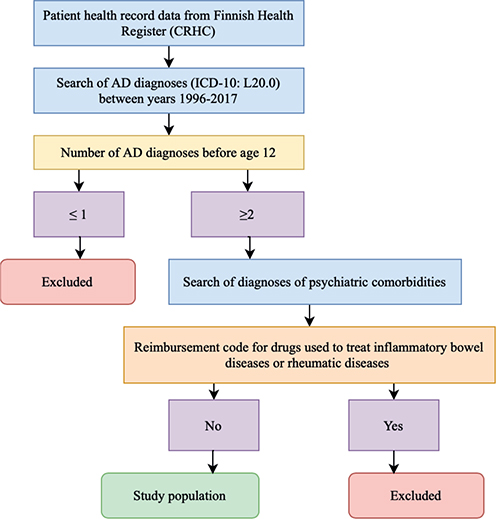

A search was conducted based on the diagnosis code of AD (code L20.0 in the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases [ICD] –-Tenth revision) between 1996 and 2017. Only individuals who had their first recorded AD diagnosis code before the age of 12 years and had the AD diagnosis code registered at least twice were included in the study population. Then, diagnosis codes for psychiatric comorbidities following AD diagnosis (Table I) were searched from CRHC for these individuals at both age of < 18 and ≤ 30 years.

The entirety of subjects were divided into 4 subpopulations, i.e., the AD severity groups presented in Table II.

| AD severity group | Females, n (%) | Males, n (%) | Total |

| No purchased treatments | 2,550 (20.4) | 3,211 (20.9) | 5,761 |

| Mild or moderate TGC or TCI | 6,739 (53.9) | 8,286 (53.9) | 15,025 |

| Potent or very potent TGC | 3,197 (25.6) | 3,852 (25.1) | 7,049 |

| Systemic treatmenta | 16 (0.1) | 16 (0.1) | 32 |

| Patients were hierarchized from “potent- or very potent topical glucocorticoids (TGC)” to “no purchased treatments” and an individual was allocated to 1 group only. TCI: topical calcineurin inhibitor. aIncluding cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and dupilumab. Systemic steroids were not included. Those who had a reimbursement code for drugs also used to treat inflammatory bowel diseases or rheumatic diseases were excluded from the final group, as such medications were most likely prescribed for disorders other than the patients’ AD. |

|||

The severity of AD was defined by using the purchased AD treatments as a proxy for AD severity (12). Classification was based on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification. Data on purchased AD medications were collected from the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (KELA), which holds records of all reimbursements for medicinal expenses. Only medications purchased after the first recorded AD diagnosis and onwards were used in the subgrouping. A flowchart of inclusion criteria is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flow-chart of the formation of the study population

The characteristics of study population are presented as numbers and proportions. The association between the groups was evaluated by logistic regression model. Results are presented as crude and adjusted (by birth year) ORs (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). AD cases without purchased medications were used as the reference group. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software package (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and the R software package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Two-sided p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The database search returned 27,867 individuals fulfilling the inclusion criteria. We found that 20.1% of those treated with “mild or moderate topical glucocorticoids (TGC) or topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI)” and 20.4% of those with “potent or very potent TGC” had at least 1 recorded psychiatric diagnosis by the age of 18 years. By the age of 30 years, there were more cases with a psychiatric diagnosis (24.4% and 25.3.%, respectively), but the overall risk remained similar to that by 18 years of age (Table III). The risk of depression was already heightened among those using “mild or moderate TGS or TCI” (OR 1.27) and among those using “potent or very potent TGC” (OR 1.31) by 18 years of age when compared with those with no purchased treatment for AD.

| Psychiatric comorbidity | AD severity group | ≤ 18 years | ≤ 30 years | ||||

| n (%) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | ||

| Any psychiatric comorbiditya | No purchased treatments for AD | 986 (17.1) | Reference | Reference | 1,298 (22.5) | Reference | Reference |

| Mild or moderate TGC or TCI | 3,015 (20.1) | 1.22 (1.12–1.32) | 1.12 (1.04–1.22) | 3,659 (24.4) | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) | 1.13 (1.05–1.21) | |

| Potent or very potent TGC | 1,436 (20.4) | 1.24 (1.13–1.36) | 1.18 (1.08–1.29) | 1,781 (25.3) | 1.16 (1.07–1.26) | 1.18 (1.08–1.28) | |

| Systemic treatmentb | 6 (18.8) | 1.12 (0.46–2.72) | 1.04 (0.42–2.53) | 8 (25.0) | 1.15 (0.51–2.56) | 1.17 (0.52–2.60) | |

| Major depression | No purchased treatments for AD | 184 (3.2) | Reference | Reference | 398 (6.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Mild or moderate TGC or TCI | 638 (4.2) | 1.34 (1.14–1.59) | 1.27 (1.07–1.50) | 1,121 (7.5) | 1.09 (0.96–1.22) | 1.29 (1.14–1.46) | |

| Potent or very potent TGC | 304 (4.3) | 1.37 (1.13–1.65) | 1.31 (1.09–1.58) | 562 (8.0) | 1.17 (1.02–1.33) | 1.32 (1.15–1.52) | |

| Systemic treatmentb | 1 (3.1) | 0.98 (0.13–7.20) | 0.88 (0.12–6.52) | 3 (9.4) | 1.39 (0.42–4.60) | 1.64 (0.49–5.45) | |

| Anxiety disorders | No purchased treatments for AD | 163 (2.8) | Reference | Reference | 361 (6.3) | Reference | Reference |

| Mild or moderate TGC or TCI | 503 (3.3) | 1.19 (0.99–1.42) | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 955 (6.4) | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | |

| Potent or very potent TGC | 270 (3.8) | 1.37 (1.12–1.67) | 1.27 (1.04–1.54) | 488 (6.9) | 1.11 (0.97–1.28) | 1.18 (1.02–1.36) | |

| Systemic treatmentb | 2 (6.3) | 2.29 (0.54–9.66) | 1.91 (0.45–8.13) | 4 (12.5) | 2.14 (0.75–6.13) | 2.28 (0.79–6.59) | |

| Anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform, and other nonpsychotic mental disorders | No purchased treatments for AD | 244 (4.2) | Reference | Reference | 491 (8.5) | Reference | Reference |

| Mild or moderate TGC or TCI | 743 (4.9) | 1.18 (1.01–1.36) | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) | 1,271 (8.5) | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | |

| Potent or very potent TGC | 395 (5.6) | 1.34 (1.14–1.58) | 1.27 (1.08–1.49) | 675 (9.6) | 1.14 (1.01–1.28) | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | |

| Systemic treatmentb | 2 (6.3) | 1.51 (0.36–6.34) | 1.32 (0.31–5.61) | 4 (12.5) | 1.54 (0.54–4.39) | 1.69 (0.59–4.88) | |

| Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | No purchased treatments for AD | 503 (8.7) | Reference | Reference | 544 (9.4) | Reference | Reference |

| Mild or moderate TGC or TCI | 1,550 (10.3) | 1.20 (1.08–1.34) | 1.10 (0.99–1.22) | 1,635 (10.9) | 1.17 (1.06–1.30) | 1.08 (0.98–1.20) | |

| Potent or very potent TGC | 722 (10.2) | 1.19 (1.06–1.34) | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 767 (10.9) | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | |

| Systemic treatmentb | 5 (15.6) | 1.94 (0.75–5.06) | 1.81 (0.69–4.75) | 5 (15.6) | 1.78 (0.68–4.64) | 1.68 (0.64–4.39) | |

| All psychotic disordersc | No purchased treatments for AD | 73 (1.3) | Reference | Reference | |||

| Mild or moderate TGC or TCI | 156 (1.0) | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 1.11 (0.82–1.49) | ||||

| Potent or very potent TGC | 97 (1.4) | 1.09 (0.80–1.48) | 1.38 (1.00–1.90) | ||||

| Systemic treatmentb | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | ||||

| Bipolar disorder and manic episodesc | No purchased treatments for AD | 32 (0.6) | Reference | Reference | |||

| Mild or moderate TGC or TCI | 80 (0.5) | 0.96 (0.64–1.45) | 1.41 (0.90–2.18) | ||||

| Potent or very potent TGC | 54 (0.8) | 1.38 (0.89–2.14) | 1.88 (1.19–2.98) | ||||

| Systemic treatmentb | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | ||||

| Disorders of adult personality and behaviourc | No purchased treatments for AD | 72 (1.2) | Reference | Reference | |||

| Mild or moderate TGCor TCI | 178 (1.2) | 0.95 (0.72–1.25) | 1.52 (1.12–2.05) | ||||

| Potent or very potent TGC | 93 (1.3) | 1.06 (0.78–1.44) | 1.55 (1.12–2.15) | ||||

| Systemic treatmentb | 1 (3.1) | 2.55 (0.34–18.9) | 4.26 (0.57–32.1) | ||||

| aIncluding all studied psychiatric disorders (Table SI). bIncluding cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and dupilumab. Systemic steroids were not included. cAnalysed only for ≤ 30-year-olds, as these diagnoses are not usually set for those ≤ 18 years. Adjustments were made by year of birth. AD: atopic dermatitis; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; NA: not available; TGC: topical glucocorticoids; TCI: topical calcineurin inhibitor. |

|||||||

The risk of “anxiety disorders” (OR 1.27 in ≤ 18-year-olds and 1.18 in ≤ 30-year-olds) and “anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform and other nonpsychotic mental disorders” (OR 1.27 and OR 1.23, respectively) was heightened among those using “potent or very potent TGC” compared with those with no purchased treatments for AD. Among diagnoses belonging to the latter diagnosis group, we found an increased risk of panic disorder in patients aged 30 using “mild or moderate TGC or TCI” (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.05–1.99) and “potent or very potent TGC” (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.02–2.05). The risk of “bipolar disorders and manic episodes” was almost twofold (OR 1.88) among those using the most potent topical treatments when compared with those with “no treatment”. We did not find any differences in the risk of behavioural disorders (F90–98, including hyperkinetic disorder) or psychotic disorders (Table III). No differences between sexes were found (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We found that increased disease severity of childhood-onset AD was associated with heightened risk of several psychiatric conditions in both ≤ 18- and ≤ 30-year-old AD patients. It is noteworthy that in our study the risk of depression was already heightened at the age of ≤ 18 years even among those treated with “mild to moderate TGC or TCI”. In children, severe AD has been associated with an over twofold increase in the likelihood of symptoms of depression and internalizing symptoms across childhood in a longitudinal cohort study from the UK (13). However, a nationwide Korean registry study reported even higher risk of depression, as they reported an over threefold risk in severe AD and a 1.75-fold risk in moderate AD (14). Their study population included all age groups, but they did not analyse those with childhood-onset AD separately. Similarly, a German cross-sectional study reported an association between severe AD and severe depression (15). Equally, a Danish questionnaire-based cohort study found an association between the use of antidepressants and moderate-to-severe (hospital-diagnosed) AD, but not with mild AD (16). However, it is of note that both of these studies included adults only.

We found an increased risk of anxiety disorders among those medicated with “potent or very potent TGC” at both age < 18 and ≤ 30 (OR 1.27 and 1.18, respectively) compared with those with no purchased treatment for AD. The aforementioned Korean study reported odds of anxiety increasing as the severity of AD increased (OR for moderate AD was 1.59 and 2.64 for severe AD) as well, but it is of note that their definitions for severity groups differed markedly from our study (14).

We found that the risk increased for “anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform and other nonpsychotic mental disorders” at both ages (OR 1.27 and OR 1.23, respectively) in those using “potent or very potent TGC” compared with those with no purchased treatments for AD. This aligns with a previously reported risk in adult AD patients with severe AD (6). Interestingly, in an analysis of the diagnoses of this group separately, a pronounced risk of panic disorder depending on AD severity was found: patients 30 years of age treated with “mild or moderate TGC or TCI” and “potent or very potent TGC” had a risk of panic disorder compared with those with no purchased AD treatments. A recent cross-sectional study from the Netherlands also reported an association with severe-to-moderate AD and panic disorder and other anxiety disorders (17). However, as a limitation, the psychiatric conditions according to AD severity were self-reported and the age of onset was not reported.

We have previously shown an increased risk of bipolar disorder in adults with AD (4). In this study, we found that the risk of “bipolar disorders and manic episodes” was almost twofold in patients using the most potent topical treatments when compared with those with “no treatment” by the age of 30 years. Previously, a recent cohort study in the UK reported bipolar disorder to be associated with mild or moderate AD in adults (18). However, their severity classification differed from ours: for example, all cases referred to a dermatologist were classified as severe (18). Accordingly, a longitudinal study from Taiwan reported increased risk of bipolar disorder in later life among those with AD in adolescence (19). However, the severity status of AD was not taken into consideration in this study (19).

We found no heightened risk for “behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence” (including attention-deficit disorder) according to childhood-onset AD severity in this study. In Finnish adults, an increased risk of ADHD with worse AD severity has been found (6), but the study did not include data on onset age of AD. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis from the Netherlands found that children with AD have a 30–50% increased risk of developing ADHD later in life (20). Here, AD severity was not analysed (20). However, results of a Taiwanese systematic review and meta-analysis from 2024 revealed that the associations for ADHD were most prominent in studies evaluating patients with severe AD and in studies focusing on school-age children and adolescents (21).

The main strengths of this study are the high validity and completeness of Finnish medical register data and minimized selection bias as a registry-based study (22). However, as this is a registry-based study, we were unable to confirm the diagnoses found from the registry data. To enhance the reliability of the AD diagnosis even more, we included only those cases for whom it was recorded at least twice in the CRHC. Limitations include unavailability of confounder information, such as smoking, sleep impairment, educational level, and socioeconomic status. For example, sleep quality has been associated with psychiatric morbidity (23). As we had no information concerning causes of death, the risk of suicides according to AD severity could not be assessed. We also recognize the potential lack of less severe cases of psychiatric comorbidities in this study, as those can be treated in primary health care and are thus not recorded in the CRHC. However, especially among children and adolescents, referral to specialized healthcare is common if a psychiatric morbidity is suspected.

Our findings support the notion that worse AD severity heightens the comorbidity burden of patients for multiple psychiatric disorders. The relationship of childhood AD and its psychiatric comorbidities is complex due to its possibly pronounced impact on an individual’s health, especially during the developmental stages in life, and can be affected by many underlying factors, such as pruritus, sleep quality, chronic stress, social stigma, and other comorbidities. For this reason, we suggest careful evaluation of AD disease severity and mental wellness of AD patients in clinical practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Data availability statement: Our data are from the Finnish Care Register for Health Care (CRHC) (former name: the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register) maintained by the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare (THL). According to Finnish laws and regulations, the data in the social welfare and healthcare registers and documents are confidential. As a responsible authority, FinData can, on a case-by-case basis, grant permission to use the registers and documents for the purposes of scientific research. More information on research authorization applications can be found on www.findata.fi/en.

IRB approval: This study was exempted from review as it is based on medical records data only.

REFERENCES

- Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2020; 396: 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1

- Brunner PM, Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, Paller AS, Kabashima K, Amagai M, et al. Increasing comorbidities suggest that atopic dermatitis is a systemic disorder. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2016.08.022

- Radtke S, Grossberg AL, Wan J. Mental health comorbidity in youth with atopic dermatitis: a narrative review of possible mechanisms. Pediatric Dermatol 2023; 40: 977–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.15410

- Kauppi S, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, Tasanen K, Huilaja L. Adult patients with atopic eczema have a high burden of psychiatric disease: a Finnish nationwide registry study. Acta Derm Venereol 2019; 99: 647–651. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3165

- Appiah MM, Haft MA, Kleinman E, Laborada J, Lee S, Loop L, et al. Atopic dermatitis: review of comorbidities and therapeutics. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2022; 129: 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2022.05.015

- Kiiski V, Ukkola-Vuoti L, Vikkula J, Ranta M, Lassenius MI, Kopra J. Effect of disease severity on comorbid conditions in atopic dermatitis: nationwide registry-based investigation in Finnish adults. Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv00882. https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.4447

- Rønnstad ATM, Halling-Overgaard A-S, Hamann CR, Skov L, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Association of atopic dermatitis with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 79: 448–456.e30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.017

- Sandhu JK, Wu KK, Bui T-L, Armstrong AW. Association between atopic dermatitis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2019; 155: 178. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566

- Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, Girolomoni G, Puig L, Simpson EL, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy 2018; 73: 1284–1293. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13401

- Vittrup I, Andersen YMF, Droitcourt C, Skov L, Egeberg A, Fenton MC, et al. Association between hospital-diagnosed atopic dermatitis and psychiatric disorders and medication use in childhood. Br J Dermatol 2021; 185: 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19817

- Irvine AD, Mina-Osorio P. Disease trajectories in childhood atopic dermatitis: an update and practitioner’s guide. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181: 895–906. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17766

- Sinikumpu S-P, Jokelainen J, Huilaja L. The association between atopic dermatitis and acne: a retrospective Finnish nationwide registry study. Br J Dermatol 2023; 189: 242–244. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljad086

- Kern C, Wan J, LeWinn KZ, Ramirez FD, Lee Y, McCulloch CE, et al. Association of atopic dermatitis and mental health outcomes across childhood: a longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Dermatol 2021; 157: 1200. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2657

- Ahn H-J, Shin MK, Seo J-K, Jeong SJ, Cho AR, Choi S-H, et al. Cross-sectional study of psychiatric comorbidities in patients with atopic dermatitis and nonatopic eczema, urticaria, and psoriasis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019; 15: 1469–1478. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S191509

- Dieris-Hirche J, Gieler U, Petrak F, Milch W, Wildt B, Dieris B, et al. Suicidal ideation in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a German cross-sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol 2017; 97: 1189–1195. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2741

- Thyssen JP, Hamann CR, Linneberg A, Dantoft TM, Skov L, Gislason GH, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation, but not with psychiatric hospitalization or suicide. Allergy 2018; 73: 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13231

- Zhang J, Loman L, Oldhoff JM, Schuttelaar MLA. Beyond anxiety and depression: loneliness and psychiatric disorders in adults with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv9378. https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.9378

- Wan J, Wang S, Shin DB, Syed MN, Abuabara K, Lemeshow AR, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders in adults with atopic dermatitis: a population-based cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024; 38: 543–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.19518

- Wei H-T, Lan W-H, Hsu J-W, Huang K-L, Su T-P, Li C-T, et al. Risk of developing major depression and bipolar disorder among adolescents with atopic diseases: a nationwide longitudinal study in Taiwan. J Affect Disord 2016; 203: 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.012

- Schans J van der, Çiçek R, de Vries TW, Hak E, Hoekstra PJ. Association of atopic diseases and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017; 74: 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.011

- Cheng Y, Lu J-W, Wang J-H, Loh C-H, Chen T-L. Associations of atopic dermatitis with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatology 2024; 240: 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1159/000533366

- Kurki M, Sinikumpu S-P, Kiviniemi E, Jokelainen J, Huilaja L. Validation of diagnoses of atopic dermatitis in hospital registries: a cross-sectional database study from Finland. Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv7266. https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.7266

- Freeman, D, Sheaves B, Waite F, Harvey A, Harrison PJ. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2023; 7: 628–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30136-X