REVIEW ARTICLE

A Systematic Review of 207 Studies Describing Validation Aspects of the Dermatology Life Quality Index

Jui VYAS1, Jeffrey R. JOHNS2, Faraz M. ALI2, John R. INGRAM2, Sam SALEK3 and Andrew Y. FINLAY2

1Centre for Medical Education, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, 2Division of Infection and Immunity, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, and 3School of Life and Medical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK

This study systematically analysed peer-reviewed publications describing validation aspects of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and used Naicker’s Critically Appraising for Antiracism Tool to assess risk of racial bias. Seven online databases were searched from 1994 until 2022 for articles containing DLQI validation data. Methodology followed PRISMA guidelines, the protocol was registered in PROSPERO, and articles reviewed independently by two assessors. Of 1,717 screened publications, 207 articles including 58,828 patients from > 49 different countries and 41 diseases met the inclusion criteria. The DLQI demonstrated strong test–retest reliability; 43 studies confirmed good internal consistency. Twelve studies were performed using anchors to assess change responsiveness with effect sizes from small to large, giving confidence that the DLQI responds appropriately to change. Forty-two studies tested known-groups validity, providing confidence in construct and use of the DLQI over many parameters, including disease severity, anxiety, depression, stigma, scarring, well-being, sexual function, disease location and duration. DLQI correlation was demonstrated with 119 Patient Reported Outcomes/Quality of Life measures in 207 studies. Only 15% of studies explicitly recruited minority ethnic participants; 3.9% stratified results by race/ethnicity. This review summarizes knowledge concerning DLQI validation, confirms many strengths of the DLQI and identifies areas for further validation.

SIGNIFICANCE

The Dermatology Life Quality Index is a questionnaire that measures how skin disease affects people’s lives. It is commonly used because it is simple and easy to use, and the scores have meaning. This study looked at 207 published medical articles to find out about how appropriate and accurate the Dermatology Life Quality Index is to use. This confirmed the many strengths of the Dermatology Life Quality Index, supporting its very wide acceptance and use. This study provides valuable information for researchers and doctors who may want to use it in the future and continue its use in routine clinical practice as well as in clinical trials of new treatments.

Key words: Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI); validation; quality of life; patient-reported outcome measures.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2024; 104: adv41120. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v104.41120.

Copyright: © 2024 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

Submitted: Jul 16, 2024; Accepted after revision: Sep 12, 2024; Published: Nov 7, 2024

Corr: Jui Vyas, Centre for Medical Education, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, CF14 4XN, UK. E-mail: vyasjj@cardiff.ac.uk

Competing interests and funding: AYF is joint copyright owner of the DLQI. Cardiff University receives royalties from some use of the DLQI: AYF receives a proportion of these under standard university policy. JI receives a stipend as Editor-in-Chief of the British Journal of Dermatology and an authorship honorarium from UpToDate. He is a consultant for Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, ChemoCentryx, Novartis and UCB Pharma and has served on advisory boards for Insmed, Kymera Therapeutics and Viela Bio. He is co-copyright holder of HiSQOL, Investigator Global Assessment and Patient Global Assessment instruments for HS. His department receives income from royalties from the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and related instruments. SS has received an unrestricted educational grant from GSK, is a consultant for Novo Nordisk and produces educational materials for Abbvie. JV participated in an Advisory Board for Amgen, has received payment or honoraria from L’Oreal and support from UCB pharma for attending meetings. FA has received honorariums from Abbvie, Janssen, LEO pharmaceuticals, Lilly pharmaceuticals, L’Oreal, Novartis and UCB. His department receives income from royalties from the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and related instruments. JJ has no conflicts of interest to report. His department receives income from royalties from the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and related instruments.

Funding was provided by the Division of Infection and Immunity, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK.

INTRODUCTION

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (1) is the most widely used tool for clinicians and researchers to understand the burden of skin diseases on patients and to assess the effectiveness of interventions. The DLQI was created in order to measure the impact over the last seven days of skin disease on the quality of life of patients. A systematic review has identified the use of the DLQI in 454 randomised controlled trials encompassing 68 diseases and 42 countries (2). The extensive world-wide clinical use of the DLQI includes being incorporated in guidelines or registries in at least 45 countries (3).

It is important therefore that users have access to what has been published concerning the validation of this instrument. Validating quality of life questionnaires is critical to ensure they accurately and reliably measure what they intend to measure (4). However, often information is published alongside the reporting of other aspects of the use of the DLQI, resulting in much validation being difficult to identify and access. There have been systematic reviews of scoring methods applied to DLQI data (5) and of the correlation of the DLQI with psychiatric measures(6), but to date no comprehensive systematic reviews of DLQI validation has been carried out.

There have been many relevant studies published since two previous reviews (7,8) of DLQI validation. The aim of this systematic review was to identify all published aspects of DLQI validation since the DLQI was published in 1994 (1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Scope of the study

We defined validation as the collection and analysis of data to assess the validity and reliability of a Quality of Life (QoL) instrument to determine the extent to which an instrument measures what it purports to measure (4, 9). We defined patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures as those completed directly by the patient based on their own perception including: quality of life; patient satisfaction; and/or signs and symptoms.

Our eligibility criteria for validation included:

- Studies that presented data and analysis that supported validation of the DLQI e.g. factor structure, test–retest, internal consistency, responsiveness, differential item functioning (DIF), clinical meaning (Minimal Important Difference MID, Minimally Clinically Important Difference MCID), translation, cross-cultural adaptation, mapping and score banding.

- Translations and cross-cultural adaptations.

- Correlation of DLQI with other QoL/PRO measures (but not correlations with disease severity scales or non-QoL measures e.g. willingness to pay, patient satisfaction, cost-benefit.

Ineligible criteria for validation:

- Where the DLQI was used to validate another measure.

- Correlations with non-patient (physician) reported measures (mostly severity indices) e.g. PASI (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index), or correlations with clinical (laboratory) parameters e.g. T-cell counts or PROs that were not QoL measures.

Data sources

This study follows 2020 PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews (10). The study protocol and detailed search strategy was published on PROSPERO Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022308453) (11) and details are also given in the Appendix S1 DLQI Validation Studies Search strategy. Medline (Ovid), Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, SCOPUS, CINAHL(EBSCO) and PsycINFO online databases from January 1, 1994 (DLQI creation) to December 31, 2022 were searched independently by two authors (JJ, JV), and results corroborated. Search terms included ‘DLQI’ and ‘dermatology life quality index’. As complete a list as possible of validation search terms was used to ensure comprehensive coverage without creating excessive non-relevant data. Database specific “article type/study type” keywords, language keywords (English) keywords were also used to search the required types of study to be included. Because of the difficulty of age selection (16 years old and over) using database search terms, all ages were included in the search, and those below the inclusion age were filtered manually in EndNote. Duplicate records were excluded.

Search strategy/Selection

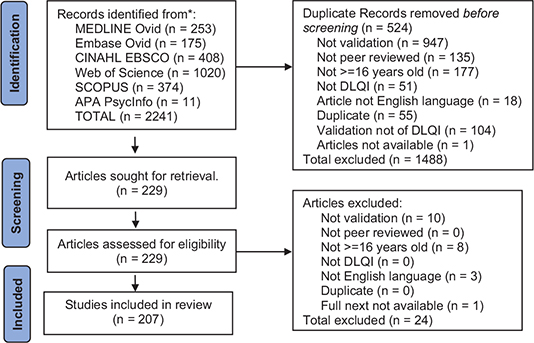

A set of eligibility criteria were applied for selection of the included studies (Table I). Search results were imported into EndNote20® (12). Two authors (JJ, JV) independently compared study titles and abstracts retrieved by searches against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and examined full study texts. Rejected studies were recorded with reasoning. A third author (FA) resolved and recorded any study selection disagreements (10) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram reporting the number of records identified from each database. Inclusion criteria applied by search engines where applicable, i.e., English language, journal articles, peer reviewed.

Data extracted

The recorded Information included the study aim, disease studied, disease severity, research setting, e.g. trial, hospital, clinic, community, single or multi-centred, number of sites, study countries, the number of subjects for which DLQI data was collected, the study type and design of the original data collected, DLQI mean scores at baseline and DLQI endpoints, and details of validation methods used including type, statistical test or specific analysis methods e.g. exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for factor structure, test–retest, internal consistency, responsiveness, clinical meaning (MCID) and validity. Data on cross-cultural adaptations and DIF were also collected. For convergent validity, only correlations with other PRO QoL measures were included (Appendix S1). Known group analysis was captured when statistical testing was applied to defined groups where there would be an expected difference e.g. disease severity as the anchor. However, when there was no indication from the author of the expectancy of a difference (a priori hypothesis or reference to a previously published study) by age and gender for example, the data was not extracted.

Data extraction and synthesis

For data extraction, guidance of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions was followed (13). A REDCap database (14–16) (a secure web application for building/managing online surveys and databases) was created. The authors JJ and JV independently extracted data from the included publications to parallel REDCap database tables, and an adjudicator (FA) resolved any disagreements in data extraction. Missing data were noted in the data templates, but none was sufficiently important to contact original authors. The two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias (quality) of included studies using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines (17).

Racial bias in research can also impact a study’s validity, reliability and relevancy (18–20). Minoritised populations have different outcomes, in part due to genetic ancestry (21), and thus recruiting for diversity is essential and results should be stratified by race/ethnicity if relevant to the study (22). This aspect is currently rarely addressed in systematic reviews of validation. To raise awareness of this issue, appraisal of representation of minorities ethnic participants in the studies was conducted using Naicker’s Critically Appraising for Antiracism Tool (23).

We considered disease severity as a clinical outcome, not a patient reported outcome. Good correlations would only be expected between closely related QOL measures (convergent validity) and therefore correlations between the DLQI and disease severity/burden measures (objective parameters rated by clinicians e.g. PASI) were not extracted, only correlations with other PRO/QOL measures were considered appropriate as they are different constructs.

Good correlations would only be expected between closely related QOL measures (convergent validity) and therefore correlations between the DLQI and disease severity/burden measures (objective parameters rated by clinicians e.g. PASI) were not extracted, only correlations with other PRO-QOL measures.

As this is a systematic review, all methods used were reported, not just those that are considered good evidence or good measurement properties (24). Thus intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), interclass relationship (ICR), Spearman’s, Pearson’s, Wilcoxon and interrater reliability kappa statistics were all reported, although only ICC and kappa measures (with their associated rating and criteria) are considered “good” methods by the COSMIN guidelines.

RESULTS

A total of 1661 studies were provided by database searching after removing 679 duplicates. After filtering these in an EndNote database for inclusion/exclusion criteria, 231 full text articles were assessed, of which 207 described research on 58,828 patients meeting the inclusion eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Publications of validation of the DLQI are increasing, with 15 new studies reported in 2022 (Fig. S1).

Study sites and settings

136 (65.7%) of the studies were conduced at a single site, 40 were multicentre (19.3%) and 27 (8.7%) did not specify, for three (1.45%) a site was not applicable, and one (0.48%) was a postal survey. Of the multicentre studies, 14 (35.0%) were conducted at two sites, 15 (37.5% at 3–10 sites, 5 (12.5%) at 11–20 sites, and 6 (15.0%) at > 20 sites. Most studies (173, 83.6%) did not involve any intervention, and were not part of a clinical trial.

The original study designs comprised one randomised control trial (RCT, blinding not specified), five RCT double blinded, four RCT single blinded, four open-label, one cohort study, 15 case controlled, 173 with no specific intervention, and two not determinable.

The design used for validation analysis comprised 28 multiple arm, 165 single arm, 172 cross sectional, 25 longitudinal, 5 placebo controlled, 1 parallel group, 2 Phase II RCT, 3 Phase III RCT, 1 Phase IV RCT and one cross-over study (some in multiple categories).

Trials were conducted in at least 49 different countries, although two reported multiple countries without listing details (Table SI). Most studies were conducted in single countries: USA (n = 21, 9.7%), Turkey (17, 7.9%), UK (15, 6.9%), China (14, 6.5), Brazil (13, 6.0%), Germany (13, 6.0%), Iran (11, 5,1%), Italy (5,1%) with 101 (46.8%) countries having <5 studies, and 21 (9.7%) countries only having a single study.

At least 33 different language variants (including specific adaptations e.g. Arabic Egypt, Arabic Lebanon, Arabic Morocco, Arabic Saudi Arabia, Arabic Tunisia) were used in the studies. 53 (37.6%) of studies did not specify explicitly which language version of the DLQI they used, while 12 studies (8.5%) used multiple language versions. The English version was the most used (39 studies, 27.7%), followed by Turkish (13, 9.2%), Portuguese (12, 8.5%), Chinese Mandarin (10, 7.1%), and Farsi (10, 7.1%).

Disease profile

Forty-one different diseases were studied. Most studies were of psoriasis (n = 52, 25.5%), followed by atopic dermatitis (n = 18, 8.8%), vitiligo (n = 14, 1.9%), acne (n = 11, 5.4%), eczema (n = 10, 4.9%), and urticaria (n = 8, 3.9%). A complete list is given in Appendix S1. Overall, studies recruited patients with mild (n = 64, 18.9%), moderate (n = 82, 24.3%) and severe (n = 81, 24.0%) disease, with 111 (32.8%) unspecified.

Content validity

Validity measures included 43 known group, 10 construct, 21 convergent, 4 concurrent, 2 divergent/discriminant, 8 content, 4 criterion, 2 face and 2 predictive validity tests using Mann-Whitney (18), Spearman’s correlation (11), Pearson’s correlation (6) and Student’s t-test (6), EFA (1), CFA (1) and 11 with other tests. DLQI responsiveness analysis was performed in 12 studies, using paired t-test (1), effect size (5), correlation of DLQI with another measures (7), Analysis of Variance test (ANOVA) (1), Wilcoxon two-sample (2) and bivariate models (1) (Table SI(A)).

Dimensionality and factor structure

A total of 28 studies applied either factor analysis or item response theory to examine the dimensionality of the DLQI. A variable number of factors (one–four) underlying the DLQI structure was demonstrated in these studies (Table SI(B)).

Test–retest reliability and internal consistency reliability

Test–retest reliability of the DLQI was assessed in 13 studies (Table II), reporting Spearman’s rank correlations between 0.97 and 0.99, a Pearson’s correlation of 0.96, ICC between 0.77 and 0.983 with 7 of 9 above 0.90, ICR of 0.96, and a Kappa of 0.83. All of these were above acceptance values (ICC very high (ICC > 0.9), high (ICC > 0.75), moderate (ICC between 0.5–0.75) (25) or Kappa 0.81–1.00 as almost perfect agreement (26), and Spearman’s between 0.7 and 0.9 indicating strong correlations (27). Test–retest intervals reported were between 5 to 10 days (to minimise under or over-estimation) in line with published recommendations (9). The internal consistency of the DLQI was assessed in 43 studies (Table II) and ranged from 0.673 to 0.997 with a mean value of 0.834 and standard deviation of 0.069. 41 out of 42 (95.3%) of Cronbach’s alpha values reported were above the acceptance value of ≥ 0.70 (17).

| Reference | Country | DLQI completed | Disease | Method used | Results | COSMIN |

| Test–retest reliability | ||||||

| Finlay 1994(1) | United Kingdom | 100 | Any skin disease | Spearman’s rank correlation | Test–retest reliability correlation coefficients Spearman rank gamma = 0-99, p < 0.0001); test–retest reliability of individual question scores (gamma =0.95–0.98, p <0.001) | ? |

| Badia 1999(34) | Spain | 246 | Eczema and psoriasis | ICC | ICC eczema 0.77, psoriasis 0.90 | + |

| Jobanputra 2000(35) | South Africa | 660 | 84 different diagnoses were made during the study. Dermatitis, including atopic and contact dermatitis (26%), psoriasis (18%), and acne (10%) were the most common disorders | Spearman’s rank correlation | r=0.97; p < 0.0001 (n = 65) | |

| Ferraz 2006(36) | Brazil | 115 | Multiple for reliability incl. onychomycosis and psoriasis (6 patients each), Contact dermatitis 4, and solar keratosis, viral warts, vitiligo (3 patients each). Lupus Erthematous for validity | ICR,Pearson’s | Pearson correlation coefficient for inter-observer reliability was 0.96 (p <0.001), n = 44 | ? |

| Takahashi 2006(37) | Japan | 197 | Acne | ICC | Test–retest reliability of the DLQI-J was slightly less than that of the original English version. n = 44 ICC=0.90) | + |

| Baranzoni 2007(38) | Italy | 22 | Any skin disease | ICC, Wilcoxon’s signed rank test | Retest at 1–2 weeks. n = 19 ICC = 0.983, p <0.001. Weighted kappa between 0.644 and 0.984 for items. No statistically significant difference found in total score between 1st and 2nd assessments (p = 0.016). p > 0.15 for all but 2 questions: symptoms p = 0.083 and clothes p = 0.096. mean DLQI 1st assessment = 9.14 ± 5.50, and 2nd assessment = 9.45 ± 5.86 | + |

| Mackenzie, 2011(39) | Canada | 60 | Psoriasis and Psoriatic arthritis | ICC | 0.96 (0.93, 0.97) (n = 60) | + |

| Madarasingha 2011(40) | Sri Lanka | 200 | Eczema (24.5%), Psoriasis (23.0%), Acne (10.0%), Vitiligo (14.5%), Infections (10.5%), Other (17.5%) | Cohen’s Kappa | Kappa test–retest reliability coefficient of 0.83 | + |

| Khoudri 2013(41) | Morocco | 244 | Psoriasis | ICC | ICC of the test–retest reliability was 0.97 for the overall DLQI and exceeded 0.70 in all scales. | + |

| Liu 2012(42) | China | 131 | Urticaria | ANOVA | ANOVA with Friedman’s test chi2 = 320.61 (p <0.001) indicated good repeatability using the DLQI of Chinese version. | ? |

| Ali 2017(43) | United Kingdom | 104 | Any skin disease | ICC, Wilcoxon’s signed rank test | ICC = 0,98; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.97–0.99 | + |

| Jesmin 2021(44) | Bangladesh | 80 | Psoriasis | ICC | ICC= 0.97 | + |

| Meneguin 2021(45) | Brazil | 188 | psoriasis, cellulitis/erysipelas, chronic ulcers and eczematous dermatosis, other dermatoses | ICC | For cases that did not show any clinical change in their disease status (n = 44), first interview media n = 9 (4.5–11), second interview after 7 to 14 days media n = 10 (5.5–11.5). ICC 0.95 (CI 0.88–0.98) | + |

| Schwartzman 2021(46) | United States | 994 | Atopic dermatitis | ICC | 0.81 (95% CI 0.76–0.85) | + |

| Internal consistency reliability studies | ||||||

| Finlay 1994(1) | United Kingdom | 100 | Any skin disease | Consistency between all questions when paired was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.002) ranging from Rank correlations of 0-23-0-70 | ? | |

| Badia 1999(34) | Spain | 246 | Eczema and psoriasis | α = 0·83 | + | |

| Jobanputra 2000(35) | South Africa | 660 | 84 different diagnoses were made during the study. Dermatitis, including atopic and contact dermatitis (26%), psoriasis (18%), and acne (10%) were the most common disorders | α = 0.83. The inter-item rank correlation coefficients ranged from 0.04 to 0.54 | + | |

| Zachariae 2000(47) | Denmark | 400 | Psoriasis, Atopic eczema, Other eczema, Urticaria, Bullous disease, Erythroderma, Hyperhidrosis, Collagenosis, Pruritus, Acne, Viral warts, Miscellaneous | α = 0.88 | + | |

| Shikiar 2003(48) | United States | 1095 | Psoriasis | Study A baseline α =0.871, week12 α =0.921; Study B baseline α =0.869, week12 α =0.919 | + | |

| Aghaei 2004(49) | Iran | 70 | Vitiligo | α = 0.77 | Cronbach’s alpha by domain, and by gender, marital status, severity, and extension of disease, and | + |

| Ilgen 2005(50) | Türkiye | 108 | Acne | α = 0.87 | + | |

| Mazzotti 2005(51) | Italy | 900 | Psoriasis | a = 0.83; item-total correlation = 0.40–0.70 | + | |

| Ozturkcan 2006(52) | Türkiye | 79 | Eczema-contact dermatitis, Psoriasis, Urticaria, chronic urticaria, Tinea, Alopecia areata, Acne | Cronbach’s α = 0.87. The item versus total (overall). Spearman’s correlation coefficients ranged from 0.48–0.81 with a median of 0.66, and the subscales versus total (overall) ranged from 0.71–0.83 with a median of 0.77. The α value was 0.84 for the age groups under 20 years and 0.89 for the 21+ years age group | males 0.83 and females 0.88; outpatients 0.86 and inpatients 0.87; eczema/acne 0.90 and other dermatological disorders 0.84). | + |

| Shikiar 2006(53) | United States | 147 | Psoriasis | α was 0.89 at baseline, 0.92 at Week 12 | + | |

| Takahashi 2006(37) | Japan | 197 | Acne | α = 0.83. Exclusion of any one of the 10 items did not increase α by > than 0.01. | + | |

| Baranzoni 2007(38) | Italy | 22 | Any skin disease | α = 0.787 for 1st assessment, 0.828 for 2nd assessment | + | |

| Mazharinia 2007(54) | Iran | 109 | Burns | Cronbach’s α for physical Q1,3,5,7,10, psychological Q2,4,6,8, and sexual domains Q9 and for total DLQI were 0.78, 0.77, 0.72, and 0.75, respectively. | + | |

| Henok 2008(55) | Ethiopia | 74 | Podoconiosis | Overall α value was 0.90, standardized item alpha 0.89. Average inter-item correlation was 0.44, item total correlation ranged from 0.15 to 0.81. Only item 6 (about sport) had a value of <0.2. The average item total correlation was 0.64. | + | |

| Aghaei 2009(56) | Iran | 125 | Psoriasis | α = 0.79 | + | |

| An 2010 (57) | China | 128 | Leprosy | Cronbach’s α = 0.765, standardized item α =0.759, | Average inter-item correlation was 0.240 (> 0.2), Item total correlation ranged from 0.212 to 0.596. Average item total correlation was 0.427. | + |

| Madarasingha 2011(40) | Sri Lanka | 200 | Eczema (24.5%), Psoriasis (23.0%), Acne (10.0%), Vitiligo (14.5%), Infections (10.5%), Other (17.5%) | Cronbach’s α 0.561 to 0.741 (except for the personal relationship domain). Healthy volunteers (n = 40): Symptoms and feelings (0.598), Daily activities (0.654), Leisure (0.569). Personal relationships (0.498). Patients (n = 200): Symptoms and feelings (0.561), Daily activities (0.741, Leisure (0.687). Personal relationships (0.442). | – | |

| Liu 2012(42) | China | 131 | Urticaria | α was 0.82, and it became 0.84 when item 1 was deleted. The α value reached 0.85 after standardization | + | |

| Maksimovic 2012(58) | Serbia | 66 | Atopic dermatitis | α = 0.84 | + | |

| Twiss 2012(59) | United Kingdom | 292 | Psoriasis and Atopic dermatitis | The Person Separation Index (PSI) indicated that the DLQI had adequate internal reliability. | + | |

| An 2013(60) | China | 395 | Neurodermatitis or psoriasis vulgaris | Cronbach’s α =0.889. Average inter-item correlation = 0.415, item-total correlation ranged from 0.483 to 0.711, average item-total correlation was 0.628. | + | |

| He 2013(61) | China | 851 | Psoriasis | α = 0.91. Exclusion of any one of the 10 items did not increase a by more than 0.01. Corrected item-total correlations ranged from 0.51 to 0.79 | + | |

| Khoudri 2013(41) | Morocco | 244 | Psoriasis | Overall 0.70 (α = 0.84) and ranged in all scales from 0.33 to 0.75. Item internal congruency 0.82– 0.90. ICC 0.85–0.97 | + | |

| Lilly 2013(62) | United States | 90 | Vitiligo | Cronbach α = 0.935. Item-total correlations ranged between 0.56 and 0.84 except for VitiQoL question 13 (‘’Has your skin condition affected your sun protection efforts during recreation?’’) with a correlation of 0.36. | + | |

| Liu 2013(63) | China | 106 | Pruritic papular eruption | α = 0.673 for the six dimensions (Symptoms and feelings, Daily activities, Leisure, Work and School, Personal relationships and Treatment) were 0.633, 0.777, 0.771, 0.785, 0.772 and 0.684 respectively. | – | |

| Lockhart 2013(64) | United Kingdom | 85 | Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia | α = 0.93 | + | |

| Thomas 2014(65) | India | 38 | Lymphatic Filariasis | α = 0.73 | + | |

| Wachholz 2014(66) | Brazil | 41 | Leg ulcers | α = 0.729 | + | |

| Qi 2015(67) | China | 698 | Alopecia | α = 0.887, standardized item alpha was 0.881, The average inter-item correlation was 0.425 (> .2), suggesting good reliability. The item total correlation ranged from 0.180 to 0.797. The average item total correlation was 0.617 | + | |

| Chernyshov 2016(68) | Ukraine | 126 | Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis | α =0.81 for AD and 0.86 for psoriasis | + | |

| Solgajová 2016(69) | Slovakia | 104 | Acne or atopic dermatitis | α = 0.82 | Note: Aghaei et al., 2004; (Liu) Zhibin et al., 2013 don’t give this value, it must be from this study! | + |

| Kirby 2017(70) | United States | 154 | Hidradenitis Suppuratvia | α = 0.90 | R, version 3.3.2 | + |

| Cozzani 2018(71) | Italy | 50 | Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis | α = 0.90 (0.88–0.92 for items). Highest value for the item-test correlation (r = 0.89) was for item 9 (interpersonal relationships), while the lowest corresponded to item 6 (leisure; r = 0.31). α increased to 0.90 only with the deletion of item 5 (sociability) | + | |

| Hunt 2018(72) | Vietnam | 102 | Leprosy | α = 0.78 | + | |

| Shimizu 2018 (73) | Brazil | 116 | Alopecia | α = 0.87 | + | |

| Xiao 2018(74) | China | 465 | Arsenic-related skin lesions and symptoms | Cronbach’s α was 0.79, and the split-half reliability was 0.77 | + | |

| Beamer 2019(75) | United States | 40 | Radio-dermatitis | α = 0.69 with work and study item was removed from analysis because the variance was zero. Inter-item correlation from 0.10 to 0.66 | Removal of treatment subscale (item) would improve alpha by .15. | – |

| Patel 2019(33) | United States | 340 | Atopic dermatitis | Cronbach’s α = 0.89. Spearman rho Interitem correlations 0.30 to 0.62 | + | |

| Satti 2019(76) | Pakistan | 173 | Uremic pruritus | α = 0.71 | + | |

| Storck 2018(77) | Germany | 79 | Pruritus | α Paper based 0.80, iPAD electronic1 0.81, iPAD electronic2 0.81 | + | |

| Temel 2019(78) | Türkiye | 150 | Acne vulgaris (AV) or vitiligo, or alopecia areata (AA) | α acne vulgaris 0.812, vitiligo 0.329, alopecia areata 0.915 | + | |

| Demirci 2020(79) | Türkiye | 100 | Psoriasis | α =0.82 (SPSS 20.0) | + | |

| Jorge 2020(80) | Brazil | 1286 | 14 dermatoses. (Basal cell carcinoma Bullous disorders, Female alopecia Genital warts, Hidradenitis suppurativa, Leprosy, Melasma, Onychocriptosis, Photoaging, Psoriasis, Rosacea, Uremic pruritus, Urticaria, Vitiligo) | Total Cronbach’s α (CI 95%) 0.90 (0.89–0.91); 0.72–0.91 for individual diseases. If any item was excluded, Cronbach’s α for the total sample ranged from 0.87 to 0.89 . | Highlighed cultural difficulty of q9 (sexual life) within the population. IRT analysis indicates that q9 is most affected with severe HRQOL impact. | + |

| Paudel 2020(81) | Nepal | 149 | Urticaria | α = 0.88, standardised 0.89, and did not change with the deletion of any of the items. The interitem correlation matrix revealed that the Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) ranged from 0.097 to 0.730. All items had a satisfactory correlation with each other. Items 1–4 α = 0.79, items 5–10 α =0.86 | + | |

| Meneguin 2021(45) | Brazil | 188 | Psoriasis, cellulitis/erysipelas, chronic ulcers and eczematous dermatosis, other dermatoses | α = 0.85 (CI 0.82–0.88) | + | |

| Pollo 2021(82) | Brazil | 281 | Psoriasis | α = 0.87 | + | |

| Kolokotsa 2022(83) | Greece | 150 | Acne | α = 0.80 | + | |

| Data was extracted from referenced publications. | ||||||

| For test–retest reliability COSMIN: “+” ICC or weighted Kappa ≥ 0.70; “?” ICC or weighted Kappa not reported; “–” ICC or weighted Kappa < 0.70. The criteria are based on Prinsen et al.(17). | ||||||

| For internal consistency reliability COSMIN: “+” At least low evidence for sufficient structural validitya AND Cronbach’s alpha(s) ≥ 0.70 for each unidimensional scale or subscaleb; “?” Criteria for “At least low evidence for sufficient structural validitya” not met; “–” At least low evidence for sufficient structural validitya AND Cronbach’s alpha(s) < 0.70 for each unidimensional scale or subscaleb. | ||||||

| aThis evidence may come from different studies. | ||||||

| bThe criteria ‘Cronbach alpha < 0.95’ was deleted, as this is relevant in the development phase of a PROM and not when evaluating an existing PROM. The criteria are based on Prinsen et al. (17) | ||||||

Responsiveness to change

Although many clinical trials have demonstrated DLQI score change in patients’ QoL before and after treatment, only 12 studies were included (Table III), where the study was specifically conducted and statistical analysis using anchors performed to assess the responsiveness to change of the DLQI. Effect sizes were reported between 0.3 and 0.82 where effects are considered small 0.2, medium 0.5, large 0.8 and very large 1.3 (28). Pearson’s/Spearman’s correlations with other measures ranged from –0.35 to 0.75 with correlation of ±0.2 small, ±0.5 medium and ±0.8 large (28). Significant responsiveness by ANOVA and Wilcoxon 2-sample (paired) analysis was also demonstrated. Although in assessing responsiveness to change, the effect size of change is not informative according to COSMIN, however, as this is a systematic review we have reported all validation data. The method for calculating effect size is missing for some studies where it was not reported.

| References | Country | DLQI completed | Disease | Methods | Results | Method other | COSMIN |

| Badia 1999(34) | Spain | 246 | Eczema and psoriasis | Effect size (ES) | Effect sizes (ES) for changes in overall DLQI score between visits 1 and 3 were 0·82 for eczema patients and 0·58 for psoriasis patients | ? | |

| Shikiar 2003(48) | United States | 1095 | Psoriasis | Correlation of DLQI with other measure, ANOVA | Pearson’s correlations Among Change Scores of DLQI and change scores of Study 1 PASI (0.47), OLS (0.43) and PGA (0.46); Study 2 PASI (0.54), OLS (0.46) and PGA (0.53) all p <0.001. | ANOVA of DLQI Among Three Groups of PASI Improvement Scores:≥ 75%; Between 50% and 75%; and < 50%: Study A mean change score (N) <50% 4.79 (230), ≥ 50% and <75% 13.53 (96), ≥ 75% 18.63 (110), F statistic=54.61 p <0.0001. Study B mean change score (N) <50% 2.49 (268), ≥ 50% and <75% 6.83 (146), ≥ 75% 10.03 (122), F statistic=75.05, p <0.0001 | + |

| Shikiar 2006(53) | United States | 147 | Psoriasis | Correlation of DLQI with other measure | DLQI Correlations Baseline EQ-5D Index (0.51), EQ-5D VAS (–0.35); Week12 EQ-5D Index (–0.71), EQ-5D VAS (–0.58); Change EQ-5D Index (–0.53), Change EQ-5D VAS (–0.46), all p <0.001. | + | |

| Takahashi 2014(84) | Japan | 119 | Psoriasis | Correlation of DLQI with other measure | Spearman’s correlation PASI and DLQI scores. r = 0.134, P = 0.63. | + | |

| Basra 2015(85) | United Kingdom | 192 | Any skin disease | Paired t-test, Effect size (ES) | Mean DLQI total score BL 9.8 SD 7.8, follow-up 7.4 SD 7.1, mean change 2.4 t-test p = 0.001, Cohen’s effect size = 0.3, SRM 0.4 | + | |

| Richter 2017(86) | Germany | 41 | Acne | Effect size (ES) | Overall ES=0.64. Divided into the responder groups (based on Investigator Static Global Assessment; ISGA), highest ES were detected in the ‘Highly improved’ group (ISGA > =2, ES=0.66. | + | |

| Patel 2019(33) | United States | 340 | Atopic dermatitis | Effect size (ES) | Overall, DLQI scores changed significantly between baseline and the next visit. Cohen’s d = –0.74 for > =1 point POEM improvement, d=–0.72 > =3.4 point POEM improvement (MCID); d=0.28 for > =1 point POEM worsening, d=0.65 for > =0.3.4 points POEM worsening (MCID) | + | |

| Silverberg 2020(87) | United States | 118 | Atopic dermatitis | Correlation of DLQI with other measure, Wilcoxon 2-sample | Changes from baseline in PROMIS Cognitive Function T-scores were weakly inversely correlated (Spearman’s) with changes from baseline DLQI (r = –0.22, p = 0.0003) | The impact of cognitive dysfunction (PROMIS Cognitive Function T-score <=45%) on HRQOL was examined in bivariable models (Mann-Whitney U-test) stratified by Patient’s Global Assessment (PGA). There were generally stepwise increases in DLQI and ItchyQoL scores between mild, moderate, and severe AD | + |

| Silverberg 2020(88) | United States | 410 | Atopic dermatitis | Correlation of DLQI with other measure | NRS worse 0.26, NRS average 0.33, VRS worse 0.27, VRS average 0.28, all p <0.001 | Follow-up visit duration of 0.3 ± 0.4 years (maximum 1.9 years) n = 374. Change in numeric rating scales (NRS) and verbal rating scales (VRS) vs change in DLQI | – |

| Meneguin 2021(45) | Brazil | 188 | Psoriasis, cellulitis/erysipelas, chronic ulcers and eczematous dermatosis, other dermatoses | Correlation of DLQI with other measure, Wilcoxon 2-sample | Spearman’s: correlation (ρ) : Skindex-16 Total r=0.75; Sk-16 symptoms r=0.57; Sk-16 emotions r=0.66; Sk-16 functionality r=0.70 | For patients showing clinical improvements using the Wilcoxon test, First interview media n = 10 (6.5–15.5); second interview after 7 to 14 days media n = 7.50 (4.5–13); p <0.01 | + |

| Schwartzman 2021(46) | United States | 994 | Atopic dermatitis | Correlation of DLQI with other measure, Wilcoxon matched | Change in DLQI score with change PGH T scores. Change in DLQI score with change PO-SCORAD r=0.39, change PHQ-9 r=0.41, change PROMIS sleep Disturbance r=0.40, change PROMIS sleep Related impairment r=0.22, change Objective SCORAD r=0.53, change SCORAD r=0.58, all p <0.001 | + | |

| Papoui 2022(89) | Cyprus | 38 | Pruritus | Effect size (ES) | Control Group Mean DLQI ± SD, Week 1 7.9 ± 6.2 Week 2 9.6 ± 6.2 Week 3 9.7 ± 5.3; Intervention Group Mean DLQI ± SD, Week1 8.7 ± 7.4 Week2 7.9 ± 4.7 Week3 7.5 ± 4.7 Cohen’s d Week1, –0.12 Week2 0.31 Week3 0.44 | + | |

| Data was extracted from referenced publications. | |||||||

| COSMIN: “+” The result is in accordance with the hypothesis OR AUC ≥ 0.70; “?” No hypothesis defined (by the review team); “–” The result is not in accordance with the hypothesis OR AUC < 0.70. The criteria are based on Prinsen et al.(17) | |||||||

Studies assessing known group analysis of the Dermatology Life Quality Index

Table SI(C) shows studies where known group validity (i.e. a type of construct validity) analysis was performed on the DLQI. We included studies where known group analysis was performed, even if the authors had not stated an a priori hypothesis. Only four studies reported effect sizes. A majority of the statistical tests performed in the known group analyses (Student’s t, Pearson’s correlation, Spearman’s correlation, Mann-Whitney U-test, Kruskal-Wallis) to discriminate between the studies groups showed statistical significance. Known-groups validity evidence is essential to provide confidence in the construct and use of a measure, and the DLQI demonstrates this over a wide variety of groups (e.g. disease severity, anxiety, depression, stigma, scarring, well-being, sexual function, disease location, disease duration, race).

Studies assessing the correlation of the Dermatology Life Quality Index with other PRO/QoL instruments

In many studies, the DLQI was used in parallel with other instruments, some generic, some dermatology-specific and disease-specific measures. In this systematic review we captured correlations of the DLQI with PRO/QOL instruments reflecting its construct validity (or more specifically its convergent validity as shown in Table IV). The working definition of PRO/QoL is listed in the Appendix S1. Correlations with non-PRO or non-QoL measures e.g. severity scales were not included. Of 133 studies that published correlations, almost all were Spearman’s or Pearson’s with one Kendall’s tau correlation, one Wilcoxon test and 14 studies did not specify.

| References | Country | DLQI completed | Disease | Measure | Methods | Results | COSMIN hypothesis | |||

| Herd 1997(90) | United Kingdom | 56 | Atopic dermatitis | Patient Generated Index (PGI) | not stated | Correlation between DLQI and PGI was –0.52 (P <0.001). For DLQI Q1 to 10 r= –0.36*, –0.51**, –0.39*, –0.42**, –0.40*, –0.27, –0.20, –0.19, –0.13, –0.32; * p <0.01, ** p <0.001 | 2* | |||

| Badia 1999(34) | Spain | 246 | Eczema and psoriasis | Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) | Spearman’s | Correlations between DLQI scores and NHP dimensions were low to moderate, ranging from 0·32 with the NHP mobility dimension to 0·12 with the energy dimension. | 2 | |||

| Kent 1999(91) | United Kingdom | 614 | Vitiligo | 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), (Perceived) Stigma Questionnaire (adaptation of Ginsberg and Link 1989, some items dropped, replaced “psoriasis” with “vitiligo”); Self Esteem (Rosenberg 1965)(92) | not stated | GHQ-12 r=0.40, p <0.001; Perceived stigma r=0.62 p <0.001; Self Esteem r=-0.45 p <0.001 | 2* | |||

| Mallon 1999(93) | United Kingdom | 111 | Acne | SF36 | Pearson’s | SF-36 dimensions Self-esteem -0.37, Role-emotional -0.46, Social function -0.69, Mental health -0.53, Energy/vitality -0.38, all p <0.001 | 2* | |||

| Lundberg 2000(94) | Sweden | 366 | Psoriasis OR atopic dermatitis | SF36 | Spearman’s | The Spearman’s correlation coefficients between the data of SF-36 and the DLQI showed significant correlations ranging between ± 0.15 and ± 0.41. | 2 | |||

| Williamson 2001(95) | United Kingdom | 70 | Alopecia | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | Spearman’s | r= 0.62 (P <0.0001) | 2* | |||

| Sampogna 2004(96) | Italy | 786 | Psoriasis | Skindex, Impact of Psoriasis Questionnaire (IPSO), Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI), Psoriasis Life Stress Inventory, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) | Pearson’s: Correlation matrix of clinical severity, QOL & psychological distress instruments | Skindex Social functioning r=0.723, Emotions r=0.633, Symptoms r=0.452; Impact of Psoriasis Questionnaire (IPSO) r=0.758; Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI) r=0.805; Psoriasis Life Stress Inventory 0.627; General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) r=0.576. No p values given, | Skindex mostly 1 IPSO 1 PDI 1 PLSI 1 GHQ 2 |

|||

| Wittkowski 2004(97) | United Kingdom | 125 | Atopic dermatitis | Stigmatisation and Eczema Questionnaire (SEQ), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (FNE) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). | Pearson’s | SEQ r=0.56 p <0.01, HADS anxiety r=0.32 p <0.05, HADS depression r=0.49 p <0.01, FNE r=0.27 p <0.01, RSE r=0.38 p <0.01 | SEQ 2* HADS-D 2* FNE 2* RSE 2* |

|||

| Yazici 2004(98) | Türkiye | 61 | Acne | Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Pearson’s | HAD-A ( r = 0.485, P = 0.0001) and HAD-D ( r = 0.455, P = 0.0001) | HADS 2* | |||

| Ilgen 2005(50) | Türkiye | 108 | Acne | Acne Quality of Life Scale (AQOLS) | Spearman’s | AQOLS and DLQI (r=0.466, p≤0.05). | 2* | |||

| Ferraz 2006(36) | Brazil | 115 | Multiple for reliability. See suppl data for full list. Lupus Erthematous for validity. | SF36 | Pearson’s | The correlation coefficient between DLQI and each SF-36 component score were highly statistically significant (r= -0,30 to -0.56, p <0.001) | 2* | |||

| Vilata 2008(99) | Spain | 247 | Anogenital Condylomata Acuminata | CECA (Specific Questionnaire for Condylomata Acuminata) | Spearman’s | Overall r=-0.670, Emotional dimension r=-0.546, Sexual activity dimension r=-0.676 | 1* | |||

| Aghaei 2009(56) | Iran | 125 | Psoriasis | Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI) | not specified | r = 0.94 | 1* | |||

| Menter 2010(100) | United States | 96 | Psoriasis | Zung Self-rating Depression Scale | Pearson’s | Baseline: r= 0.5 p <0.0001; Score changes from baseline to wk12 r= 0.5 p <0.0001 | 2* | |||

| de Ue 2011(101) | Brazil | 62 | Urticaria | SF-36 | Spearman’s | r = 0.254 to -0.465 between the domains of the DLQI and those of the SF-36. | 2 | |||

| Goreshi 2011(102) | United States | 120 | Dermatomyositis | Skindex-29 | Pearson’s | Each Skindex-29 subscore significantly correlated with DLQI scores (Skindex-29 Symptom r=0.632, Skindex-29 Emotion r=0.674, Skindex-29 Function r=0.856; all p values<0.0001) | 1* | |||

| Kluger 2011(103) | France | 18 | Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome (facial fibrofolliculomas) | Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) | Spearman’s | r=0.83 | 1 | |||

| Lau 2011(104) | Australia | 119 | Contact dermatitis | ShortFormHealthSurvey (SF-36) | Spearman’s | SF-36 PCS 0.253 (p <0.01); MCS −0.298 (p <0.002) | ||||

| Tadros 2011(105) | Greece | 80 | Psoriasis | Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI) | Spearman’s | DLQI was significantly and positively correlated with FDLQI (Spearman r = 0.51, P <0.001) | 1^ | |||

| Fernandez-Penas 2012(31) | Spain | 144 | Psoriasis | Skindex-29 | Spearman’s | r ≥ 0.57 for DLQI total score and Skindex-29 subscales (0.73 symptoms, 0.73 emotions and 0.57 functioning, all p <0.01). Correlations of DLQI items and Skindex-29 subscales 0.37 to 0.73 (all p <0.01, n = 144) | 1* | |||

| Ghajarzadeh 2012(106) | Iran | 300 | Psoriasis, vitiligo, alopecia areata | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | Pearson’s | All r=0.44 p <0.001. Significant correlation between DLQI and BDI in all groups: vitiligo (r=0.5, P <0.001), psoriasis (r=0.3, P=0.001), AA (r=0.34, p <0.001) | 2* | |||

| Ghajarzadeh 2012(107) | Iran | 100 | Alopecia | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | Pearson’s | r=0.34 p value < 0.001 | 2* | |||

| Kimball 2012(108) | United States | 1212 | Psoriasis | Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire for Psoriasis (WPAI-Psoriasis) | Pearson’s | Correlation coefficients = 0.57, 0.58, 0.66, and 0.28 for TAI, TWPI, presenteeism, and absenteeism, respectively | 1 | |||

| Maksimovic 2012(58) | Serbia | 66 | Atopic dermatitis | SF36 | Spearman’s | Correlation coefficients between SF-36 and DLQI scales ranged between -0.26 and -0.38, most p <0.01. The highest correlations were seen between symptoms and feelings and daily activities (q = 0.75; P <0.01), symptoms and feelings and work ⁄school (q = 0.56; p <0.01), and leisure and work ⁄school (q =0.53; P <0.01) for subscales of the DLQI. | 1* | |||

| Norlin 2012(109) | Sweden | 2191 | Psoriasis | EQ-5D | Spearman’s | r = 0.55, p <0.001 (n = 2091; adjusted R2 =0.28; Root Mean Square Error = 0.1989; Probability > F =0<0.0001) | 1* | |||

| Yu 2012(110) | Korea South | 138 | Eczema/Hand eczema | Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-II) scoring system | Spearman’s | BDI-II scores also had a positive correlation with DLQI score (p<0.05) | ||||

| Bin Saif 2013(111) | Saudi Arabia | 141 | Vitiligo | Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI) | not stated | r = 0.56, p <0.001 | 1* | |||

| Ghaderi 2013(112) | Iran | 70 | Acne | SF-36 | Pearson’s | r=-0.46 p <0.001; Physical functioning (PF) r= −0.20 p = 0.10; role physical (RP) r=-0.37 p = 0.002; role emotional (RE) r=-0.49 p <0.001; vitality (VT) r=-0.36 p = 0.002; mental health (MH) r=-0.19 p = 0.11; social functioning (SF) r=-0.21 p = 0.09; bodily pain (BP) r=-0.31 p = 0.009; general health (GH) r=-0.38 p = 0.001 | 2* | |||

| Lilly 2013(62) | United States | 90 | Vitiligo | Vitiligo-specific quality-of-life instrument (VitiQoL) | Pearson’s | total VitiQOL (0.832), Interpersonal (0.752), Emotion (0.842), Grooming (0.499), all p <0.05 | 1* | |||

| Lindberg 2013(113) | Sweden | 93 | Eczema/Hand eczema | EQ5D | Spearman’s | EQ5D-VAS (−0.62), and the EQ5D-index (−0.67) , both p <0.05 | 1* | |||

| Lockhart 2013(64) | United Kingdom | 85 | Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia | Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia questionnaire (VIN) | not stated | VIN questionnaire score was statistically significantly correlated with the DLQI (r = 0.69). VIN questions which related to symptoms and activities of daily life correlated strongly with the DLQI questionnaire, with correlations ranging from 0.45 to 0.62 | 2* | |||

| Rizwan 2013(114) | United Kingdom | 178 | Photodermatoses | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), social anxiety using the Fear of Negative Evaluation measure (FNE), coping strategies (brief COPE) | Pearson’s | DLQI scores were significantly associated with anxiety (r = 0.28, p <0.01), depression (r = 0.41, p <0.01), adaptive (r = 0.31, p <0.01) and maladaptive (r = 0.3, p <0.01) coping strategies. | HADS-D 2*, COPE adaptive 2*, maladaptive 2* | |||

| Strand 2013(115) | United States | 352 | Psoriasis | SF-36 | Pearson’s | Correlations between SF-36 scores and DLQI were moderate (r> 0.30 and ≤0.60) | 2* | |||

| Stumpf 2013(116) | Germany | 284 | Pruritus | Frankfurt Body Concept Scales (Frankfurter Körperkonzeptskalen; FKKS) | Pearson’s | Total r=-0.295 p <0.02. DLQI showed negative correlations with all subscales (r=-0.184 to 0.379, all p <0.01) and SKKO (r=-0.131, p <0.05) except SDIS and SPKF | ||||

| Tjokrowidjaja 2013(117) | Australia | 70 | Bullous disease | Treatment of Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life (TABQOL) | not specified | r = 0.64 | 2* | |||

| Vinding 2013(118) | Denmark | 177 | Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer | Skin Cancer Quality of Life (SCQoL) | Spearman’s | SCQoL Total r=0.45, p <0.0001; SCQoL Function r=0.36, p <0.0001; SCQoL Emotions r=0.44, <0.0001; SCQoL Control r=0.36, <0.001 | 1* | |||

| Yano 2013(119) | Japan | 112 | Atopic dermatitis | Work productivity and activity impairment-specific health problem (WPAI-SHP) | not specified | WPAI total work productivity impairment [TWPI] n = 97 r=0.600 p <0.001; total activity impairment [TAI]) n = 112 r=0.637 p <0.001 | 2* | |||

| Bardazzi 2014(120) | Italy | 240 | Psoriasis | Psoriasis awareness among patients in Italy questionnaire | Spearman’s | Awareness was positively correlated with QoL as measured by DLQI: pathogenesis r=0.02 p = 0.768, diagnosis r=0.11 p = 0.099, clinical course r=0.18 p = 0.005, quality of life r=0.245 p = 0.245, whole scale r=0.13 p = 0.043 | ||||

| Doʇruk Kaçar 2014(121) | Türkiye | 38 | Vitiligo | Feeling of Stigmatization Questionnaire 33-item | Kendall’s tau correlation | r=0.548, p = 0.001 | 2* | |||

| Ghaderi 2014(122) | Iran | 70 | Eczema/Hand eczema | SF-36 | Pearson’s | Correlation with SF-36 domains between -0.226 and -0.442 | ||||

| Ghaderi 2014(123) | Iran | 70 | Vitiligo | SF-36 | Pearson’s | r=-0.472, p <0.001; PF, physical functioning r=-0.199 p = 0.099; RP, role physical r=-0.327 p = 0.006; RE, role emotional r=-0.324 p = 0.006; VT, vitality r=-0.349 p = 0.003; MH, mental health r=-0.365 p = 0.002; SF, social functioning r=-0.296 p = 0.013; BP, bodily pain r=-0.360 p = 0.002; GH, general health r=-0.347 p = 0.003 | SF-36 2* | |||

| Hawro 2014(124) | Poland | 60 | Psoriasis | Basic hope inventory (BHI-12) | Pearson’s | r =-0.281; p = 0.030 | 3* | |||

| Herédi 2014(125) | Hungary | 200 | Psoriasis | EQ-5D score | Spearman’s | -0.48, p <0.05 | 2* | |||

| Susel 2014(126) | Poland | 200 | Uremic pruritus | 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) | Spearman’s | Significant negative correlation between SF-36 score and DLQI score in HD patients with UP (R = -0.29, p = 0.01) | ||||

| Takahashi 2014(84) | Japan | 119 | Psoriasis | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-30 | Spearman’s | GHQ-30 and DLQI (r = 0.487, P <0.01) | 2* | |||

| Boza 2015(127) | Brazil | 74 | Vitiligo | Vitiligo-specific health-related quality of life instrument (VitiQol) | Pearson’s | r = 0.776, p <0.001 | 1* | |||

| Bruer 2015(128) | Germany | 84 | Psoriasis | Short Form Health Survey-8 (SF-8), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Shirom Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM) | Pearson’s | SF-8 r = -0.603, p <0.001; PHQ-9 depression score r = 0.437, p <0.001; SMBM total r = 0.550, p <0.001; SMBM physical fatigue r = 0.521, p <0.001; SMBM cognitive weariness r = 0.359, p <0.001; SMBM emotional exhaustion r = 0.497, p <0.001 | SF-8 2* PHQ-9 2* SMBM 2* |

|||

| Chiang 2015(129) | United Kingdom | 105 | Alopecia | Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Pearson’s | HADS Total scores (r = 0.674, p <0.001; HADS-A (r = 0.519, p <0.001), HADS-D (r = 0.711, p <0.001) | 2* | |||

| Durai 2015(130) | India | 140 | Acne | Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) | Spearman’s | r = 0.74 p <0.0001 | 1* | |||

| Heelan 2015(131) | Canada | 94 | Bullous disease | Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire- Specific Health Problem (WPAIQ-SHP) | Spearman’s | rs = −0.221, p = 0.032 (n = 94); bivariate correlations of subset of employed persons (n = 48) rs = −0.298, p = 0.040; total activity impairment subscale (TAI) rs = −0.329, p = 0.023 | TAI 2* | |||

| Moradi 2015(132) | Iran | 71 | Psoriasis | EQ-5D | Spearman’s | EQ-5D and EQ VAS showed moderate negative correlations with DLQI (rs = -0.44 p <0.001) | 2* | |||

| Schmitt 2015(133) | Germany | 201 | Psoriasis | Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) | no specified | DLQI scores were significantly correlated with presenteeism (r = 0.47; p <0.0001) and to a lesser degree also with absenteeism (r = 0.29; p <0.001) | DLQI presenteeism 2* | |||

| Sung 2015(134) | Korea South | 66 | Pemphigus | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) | Spearman’s | GHQ positivity was associated with a higher DLQI score (p<0.0001) | ||||

| Tennvall 2015(135) | Denmark | 290 | Acitinic keratosis | Actinic Keratosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (AKQoL); EQ-5D-5; EQ-VAS | Spearman’s | AKQoL n = 283 r=0.52 (p <0.001); EQ-5D-5-L n = 273 r=−0.36 (p <0.001); EQ-VAS r=−0.21 (n = 282 <0.001) | AKQoL 1* EQ-5D-5L 2* |

|||

| Catucci Boza 2016(136) | Brazil | 117 | Vitiligo | Vitiligo-specific quality-of-life instrument (VitiQoL) | Spearman | r = 0.81; p <0.001, r = 0.36 to 0.84 (all p <0.001) for domains | 1* | |||

| Chernyshov 2016(68) | Ukraine | 126 | Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis | Skindex-16 | Spearman’s | atopic dermatitis r=0.66, p <0.001; psoriasis r=0.71, p <0.001 | 1* | |||

| Gawlik 2016(137) | Poland | 130 | Psoriasis | Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Spearman’s | DLQI and HADS-A scores (r = 0.467; p <0.001) and between the DLQI and HADS-D scores (r = 0.569; p <0.001). | 2* | |||

| Ko 2016(138) | Taiwan | 480 | Psoriasis | EQ5D and VAS | not stated | EQ-5D (r=0.416**, p <0.01) and VAS (r=0.369**, p <0.01) were significantly correlated with every dimension (p <0.01) of the DLQI. Sub-analysis for mild, moderate and severe groups | 2* | |||

| Kong 2016(139) | Korea South | 50 | Atopic dermatitis | Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) | Pearson’s | r = 0.388, p = 0.04 | 2* | |||

| Kouris 2016(140) | Greece | 80 | Psoriasis | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Pearson ‘s | Within the group of psoriasis patients was a higher quality of life impairment significantly correlated with higher anxiety (r=0.27; p = 0.02), higher loneliness and social isolation (r=0.54, p <0.001), and lower self-esteem (r=-0.48, p <0.001). | ||||

| Maranzatto 2016(141) | Brazil | 154 | Melasma | Melasma Quality of Life Scale (MELASQoL) | Spearman’s | r=0.70 (p <0.01) | 1* | |||

| Salman 2016(142) | Türkiye | 148 | Vitiligo and acne patients with facial involvement | Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Pearson’s | Vitiligo: LSAS r=0.511 p <0.05; HADS r=0.574, p <0.05. Acne: LSAS r=0.478 p <0.05; HADS r=0.401, p <0.05 | LSAS 2* HADS 2* |

|||

| Sarhan 2016(143) | Egypt | 75 | Vitiligo | Arabic Version of the Female Sexual Functioning Index (AVFSFI) | Pearson’s | DLQI score was significantly correlated with AVFGSIS alone and with AVFSFI alone and with both AVFGSIS and AVFSFI (p <0 .01) | ||||

| Alarcon 2017(144) | Spain | 100 | Acitinic keratosis | Actinic Keratosis Quality of Life (AKQoL) | Spearman’s | Total score r=0.87; Function r=0.75; Emotions r=0.78; Control r=0.75; Global item r=0.76 | 1* | |||

| Augustin 2017(145) | Multiple | 340 | Psoriasis | Patient Benefit Index (PBI) | Spearman’s rank correlation | r=-0.29 p <0.001 (week 4) to r=-0.49 p <0.001 (week52, LOCF, last observation carried forward)) | 2* | |||

| Březinová 2017(146) | Czech Republic | 128 | Atopic dermatitis | Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ), Family Dermatolology Life Quality Index (FDLQI), | not stated | B-IPQ r=0.42, p <0.001; FDLQI r=0.52, p <0.001 | B-IPQ 2* FDLQI 1* |

|||

| Catucci Boza 2016(136) | Brazil | 93 | Vitiligo | Vitiligo-specific quality-of-life instrument (VitiQoL) | Spearman’s | r= 0.81; p <0.001 | 1* | |||

| Janse 2017(147) | Netherlands | 300 | Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Psoriasis | Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) | Pearson’s | r = -0.20, P =0.003 | ||||

| Masaki 2017(148) | Japan | 133 | Psoriasis | EQ-5D | Pearson’s | R=-0.472 | 2 | |||

| Michelsen 2017(149) | Norway | 141 | Psoriatic arthritis | Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease (RAID) | Spearman’s | ρ = 0.32, p <0.001 | 2* | |||

| Müller 2017(150) | Germany | 172 | nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) | EORTC Questionnaire - Cancer (QLQ-C30) | Spearman’s | The DLQI total score was significantly associated with all functioning and symptom scales of the QLQ-C30, ranging from r (s) = 0.16 to 0.49. | ||||

| Xu 2017(151) | Korea South | 364 | See supplementary data for full list | Skindex-29, SF-36 | Spearman’s | Skindex-29: psoriasis r=0.794, vitiligo r=-0.677; SF-36: psoriasis r=--0.703, vitiligo r=-0.532, all p <0.01 | Skindex-29 1* SF-36 2* |

|||

| Yfantopoulos 2017(152) | Greece | 396 | Psoriasis | EQ-5D3L, EQ-5D-5L | Spearman’s | Correlations between EQ-5D dimensions and the DLQI sum score were all significant at least at α = 5%, with higher DLQI scores being associated with more problems on the EQ-5D scale. On average, the EQ-5D-5L items were stronger correlated with the DLQI sum score (mean q5L = 0.210 vs. q3L = 0.192, p = 0.039 based on a paired t test). | ||||

| Cozzani 2018(71) | Italy | 50 | Psoriasis and Psoriatic arthritis | PSOdisk | Pearson’s | not given | ||||

| Hassanin 2018(153) | Egypt | 100 | chronic skin disease (on the genitalia or exposed areas) | Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) | Spearman’s and Pearson’s (unspecified) | Excluding the pain domain (R: −0.16 and P: 0.12), the DLQI score was significantly negatively correlated with all sex domain scores and the total FSFI score. The R values were: −0.35, −0.48, −0.29, −0.44, −0.56, and−0.48 for desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and total scores, respectively; and the P values were: 0.003 for lubrication and < 0.001 for all other scores. | 2* | |||

| Kluger 2018(154) | Finland | 26 | Psoriasis | 15D HRQoL questionnaire (15D), the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and the Beck Depression Inventory-21 (BDI-21) | Spearman’s | The 15D score negatively correlated with the DLQI score (r = -0.492; p = 0.011) and the BDI-21 score (r = -0.592; p = 0.001) | 15D 2* BDI-21 2* |

|||

| Morice-Picard 2018(155) | France | 40 | Albinism | SF-36 and Burden of Albinism questionnaire (BoA) | Pearson’s | SF-36 (n = 40)-PCS r=−0.56 p <0.002; SF-36 MCS r= −0.9 p <0.0013; Burden of Albinism questionnaire (BoA) Global score r= 0.68 p <0.0001 | SF-36 2* BoA 1* |

|||

| Tekin 2018(156) | Türkiye | 131 | Psoriasis | Anxiety and Depression Scale HAD-A, HAD-D, Type D Personality Scale (DS-14) and subscales: Negative Affectivity (NA) and Social Inhibition (SI) | Pearson’s | Correlations HAD-A 0.612, HAD-D 0.471, DS-14 0.494, subscales: NA 0.412, SI 0.501, PASI 0.360. All p <0.01 | HADS 2* DS-14 2* SI 2* |

|||

| Vakharia 2018(157) | United States | 210 | Atopic dermatitis | ItchyQoL | Spearman’s | DLQI, ItchyQoL and 5-D itch scale all significantly correlated with each other, ranging from 0.36-0.73 (P <0.0001). | 1* | |||

| Wang 2018(158) | Australia | 61 | Bullous disease | Specific Health Problem (WPAIQ-SHP) | Spearman’s | WPAIQ-SHP Presenteeism rs = 0.90, P = 0.00001; Total work productivity impairment rs = 0.88, P = 0.000035; Total activity impairment rs = 0.47, P = 0.00048 | 2* | |||

| Wu 2018(159) | China | 397 | Rosacea | Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Pearson’s | Total DLQI score of patients of patients with rosacea was positively related with anxiety (r = 0.526, p <.001) and depression scores (r = .399, p <.001) in HADS. | 2* | |||

| Albuquerque 2019(160) | Brazil | 104 | Leprosy | SF-36 | Spearman. Total and correlation between all DLQI and SF36 items | r = -0.58, p <0,01 | 2* | |||

| Arents 2019(161) | Multiple | 1189 | Atopic dermatitis | Atopic Eczema Score of Emotional Consequences (AESEC), HADS Anxiety and Depression Scale-D7 | Spearman’s ρ | AESEC (0.546, p <0.001, 95%CI =0.505, 0.585), HADS-D7 (ρ=0.461 p <0.001), 95%CI=0.414, 0.505) | AESEC 1* HADS-D7 2* |

|||

| Kalboussi 2019(162) | Tunisia | 150 | Contact dermatitis | Work Productivity and Activity Impairment: Allergy Specific (WPAI:AS) Questionnaire | Pearson’s | The DLQI score was significantly associated with atopy (p = 0.03), relapses strictly greater than 10 (p = 0.02), presenteeism (p <10−3), overall work productivity loss (p = 0.01), and daily activity impairment (p = 0.03) | ||||

| Le 2019(163) | Vietnam | 136 | Eczema/Hand eczema | EQ5D | Spearman’s | r=-0.73 | 2* | |||

| Narang 2019(164) | India | 179 | Superficial cutaneous dermatophytosis | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) | Spearman’s | r = 0.30; P <0.05 | 2* | |||

| Patro 2019(165) | India | 294 | Superficial dermatophytic infection | 5Dpruritus scale | Pearson’s | r=0.802 p <0.0001 | 1* | |||

| Satti 2019(76) | Pakistan | 173 | Uremic pruritus | Public Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | Spearman’s | r=0.69, p = 0.01 | 2* | |||

| Stefanidou 2019(166) | Greece | 103 | Pruritus | SF-6D | Spearman’s | rho = − 0.617, p <0.001 | 2* | |||

| Temel 2019(78) | Türkiye | 150 | Acne vulgaris (AV) or vitiligo, or alopecia areata (AA) | Internalized Stigma Scale (ISS) | not specified | Acne: ISS and DLQI (r = 0.596, P <0.001); Vitiligo:ISS and DLQI (r = 0.540, P <0.001) ; Alopecia areata:ISS and DLQI (r = 0.508, P <0.001) | 2* | |||

| Zeidler 2019(167) | Multiple | 535 | See supplementary data for full list | ItchyQoL | Pearson’s | r = 0.72. P = 0.001 | 1* | |||

| Demirci 2020(79) | Türkiye | 100 | Psoriasis | Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Pearson’s | DLQI scores were significantly and positively correlated with HADS anxiety scores (r=0.205, P <0.05), depression scores (r= 0.269, P <0.01) | ||||

| Gerdes 2020(168) | Germany | 538 | Psoriasis | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) | Wilcoxon test | The correlation of DLQI and BDI-II scores was highly significant (p <0.0001) | ||||

| Namdar 2020(169) | Türkiye | 71 | Psoriasis | Toronto Alexithymia Scale, Beck’s Depression Scale, Beck’s Anxiety Scale | Spearman’s | DLQI score of psoriasis patients and anxiety (r=0.342 P <0.001), depression (r=0.327 P=0.006), alexithymia (r=0.341 P=0.004), and PASI scores (r=0.389 P=0.001) | All 2* | |||

| Oosterhaven 2020(170) | Netherlands | 294 | Eczema/Hand eczema | Quality of Life in Hand Eczema Questionnaire (QOLHEQ) | Pearson’s | r=0.77, no p value given | 1 | |||

| Passlov 2020(171) | Sweden | 21 | Eczema/Hand eczema | Activities of daily living (ADL) | Spearman’s | rho = 0.72, p = 0.00022 | 2* | |||

| Silpa-archa 2020(172) | Thailand | 104 | Vitiligo | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | Pearson’s | r= 0.524, p <0.001 | 2* | |||

| Stepien 2020(173) | Poland | 240 | Pruritus | 12-Item Pruritus Severity Scale (12-PSS) | Spearman’s | p = 0.54 | 1* | |||

| Tawil 2020(174) | Lebanon | 152 | Urticaria | Arabic Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL) | Pearson’s | r = 0.86 p <0.001. Correlations between each corresponding domain of the CU-Q2oL and the DLQI were found to be moderate to strong (≥ 0.5, p<0.001). | 1* | |||

| Acar 2021(175) | Türkiye | 200 | Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) in rosacea | Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) | Spearman’s correlation | r=0.39; p = 0.017 | ||||

| Bakar 2021(176) | Malaysia | 174 | Psoriasis | Malay Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Pearson’s | There is positive correlation between HADS-D and DLQI (r = 0.421, p-value <0.001) and between HADS-A and DLQI (r = 0.465, p-value <0.001). | 2* | |||

| Barbieri 2021(177) | United States | 764 | Atopic dermatitis | DLQI-R and SF-12 | Spearman’s | DLQI-R scoring modification had stronger correlation with the SF-12 Physical Health Score p = 0.02) and SF-12 Mental Health Score (−0.44 vs −0.41, Steiger’s Z p <0.001) (−0.09 vs −0.07, Steiger’s Z p = 0.02) | 2* | |||

| Chaudhary 2021(178) | India | 35 | Leprosy | Stigma Assessment and Reduction of Impact (SARI) scale v.1.1 | Spearman’s | r = - 0.272, p = 0.113 | ||||

| Emre 2021(179) | Türkiye | 105 | Urticaria | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | Spearman’s | r =0.073 | ||||

| Erol 2021(180) | Türkiye | 105 | Urticaria | Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) | unspecified | r = 0.302, P = 0.002 | 2* | |||

| Esposito 2021(181) | Italy | 105 | Psoriasis and Psoriatic arthritis | Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) | not stated | SDS and the DLQI were strongly correlated (r = 0.71, p <0.001) | SDS 2* | |||

| Ferrucci 2021(182) | Italy | 300 | Atopic dermatitis | Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Pearson’s | HADS depression r = 0.49, p <0.01; HADS anxiety r = 0.47, p <0.01 | 2* | |||

| Gundogdu 2021(183) | Türkiye | 51 | Psoriasis | Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI) | Spearman’s | r = 0.641 P = 0.000 | 1* | |||

| Kirby 2021(184) | United States | 441 | Hidradenitis Suppuratvia | Patient global assessment (PtGA) for hidradenitis suppurativa | Spearman’s | r = 0.78, 95% CI 0.74-0.82 | 1* | |||

| Kurhan 2021(185) | Türkiye | 129 | Contact dermatitis | Social Appearance Anxiety Scale (SAAS), HADS | Pearson’s | SAAS r=0.060, no sig., HADS-A r=0.263 p <0.01, HADS-D r=0.006 not sig. | SAAS 2* | |||

| Morioke 2021(186) | Japan | 48 | Recurrent angiodema | Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL) | Spearman’s | Total AE-QoL r=0.631, p <0.001; Changes in DLQI (delta DLQI) score and those in AE-QoL scores were positively correlated r =0.48, p <0.001 | 1* | |||

| Pollo 2021(82) | Brazil | 281 | Psoriasis | Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Spearman’s | HADS-A r=0.40 p <0.05; HADS-D- r=0.40 p <0.05 | 2* | |||

| Segal 2021(187) | Israel | 58 | Pemphigus | Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) | Pearson’s | Several IP variables (timeline cyclical 0.30 p <0.05, treatment control 0,26 p <0.05, emotional representations 0.31 p <0.05, psychological attributions 0.37 p <0.01) showed correlation with DLQI, and no such correlation was found for Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). | 2* | |||

| Silverberg 2021(188) | United States | 458 | Atopic dermatitis | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) & abridged version (PHQ-2) | Spearman’s | PHQ-9 was strongly correlated with DLQI (r=0.50) and PHQ-2 (r=0.48) and change in DLQI with change in PHQ9 (r=0.42) and PHQ-2 (r=0.33), p <0.001 for all | PHQ-9 2* PHQ-2 2* |

|||

| Singh 2021(189) | India | 1392 | Acne | Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) | Spearman’s | r=0.71 | 1 | |||

| Solmaz 2021(190) | Türkiye | 306 | Psoriasis | Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) | Spearman’s | DLQI scores and IPQ-R subscales of Illness identity (r = 0.420) and Consequences (r = 0.408, p<0.001), Personal attributions (r = 0.277), Chance factor (r = 0.222), and External attributions (r = 0.212, p<0.001). | IPQ-R Illness Identity and Conseq. 2* | |||

| Talamonti 2021(191) | Italy | 174 | Atopic dermatitis | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Pearson’s | BDI r=0.306 (p = 0.001); TAS-20 r=0.1874 (p = 0.040) | BDI 2* | |||

| Zhao 2021(192) | China | 182 | Vitiligo | Vitiligo specific quality of life instrument (VitiQoL) | method not specified | r= 0.70 (P <0.01) | 1* | |||

| Aminizadeh 2022(193) | Iran | 200 | Any skin disease | Skindex-29 | Spearman’s | r=0.719, subscales Skindex-29, r from 0.24 to 0.71, P <0.01) | Overall Skindex-29 1* |

|||

| Benny 2022(194) | India | 69 | Vitiligo | General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) | Spearman’s | r = 0.54 (P <0.001) | 2* | |||

| Ito 2022(195) | Japan | 400 | Alopecia | Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), SF36v2 | not stated | HADS-A r=0.42, HADS-D r=0.47, both p <0.01. SF36: PF, physical functioning -0.34, RP, role physical -0.47, BP, bodily pain -0.27, GH, general health -0.30, VT, vitality -0.28, SF, social functioning -0.43, RE, role emotional -0.48, MH, mental health -0.41, all p <0.01 | HADS 2* SF-36 all except pain and vitality 2* |

|||

| Koszoru 2023(196) | Hungary | 218 | Atopic dermatitis | Skindex-16, EQ-5D-5L, EQ VAS (0-100) | Spearman’s | Total score r=0.839; Symptoms subscale r=0.730; Emotions subscale r=0.697; Functioning subscale r=0.827; EQ-5D-5L (r= −0.848 to 1) Total r=−0.731; EQ VAS r=−0.598; all p <0.05 | 1* | |||

| Nahidi 2022(197) | Iran | 80 | Psoriasis | Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI) | Spearman’s | Meaningful relationship was noted between the quality of life of patients and their spouses (r = 0.48, P = 0.001) | 1* | |||

| Saeki 2022(198) | Japan | 73 | Psoriasis | Work Productivity and Activity Impairment- Psoriasis (WPAI- PSO) | Partial Spearman correlation coefficient ([ρ]; | In the adjusted model, the WPL score correlated with the DLQI ρ = 0.608, p <0.0001. The presenteeism score correlated with the DLQI ρ = 0.568 p <0.0001. activity impairment score correlated with the DLQI ρ = 0.530, p <0.0001 | 2* | |||

| Tan 2022(30) | Multiple | 723 | Acne | The Facial Acne Scar Quality of Life (FASQoL); Dysmorphic Concern Questionnaire (DCQ) | Pearson’s | significant correlation between DLQI and FASQoL scores (r = 0.683; P <0.001). DCQ score moderately correlated with DLQI (r = 0.47; P <0.001) | FASQoL 2* DCQ 1* |

|||

| Tee 2022(199) | Malaysia | 30 | Pemphigus | Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life (ABQOL), | Spearman’s | DLQI correlated positively with ABQOL (r = 0.84, p <0.001) | 1* | |||

| Tuchinda 2022(200) | Thailand | 130 | Chronic urticaria or eczema | 5-D itch scale | Spearman’s | all r = 0.76, p <0.0001, (CI 0.62-0.82); chronic urticaria r= 0.76 p <0.0001 (CI 0.63-0.85); eczema r=0.72 p <0.0001 (CI 0.58-0.81) | 1* | |||

| Xavier 2022(201) | Brazil | 397 | Skin picking disorder | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment Scale (GAD-7) | Pearson’s | r = 0.73 | 2 | |||

| Yang 2022(202) | Taiwan | 143 | Vitiligo | SF36 | Spearman’s | PF, physical function r=−0.079 p = 0.351 ; RP, role limitation related to physical problems r=−0.173 p = 0.039; BP, bodily pain r=−0.134 p = 0.112; GH, general health r=−0.280 p = 0.001; SF, social functioning −0.284 p = 0.001; VT, vitality r=−0.331 p <0.001; RE, role limitation related to emotional problems r=−0.289 p <0.001; MH, mental health r=−0.466 p <0.001 | ||||

| Ye 2022(203) | Korea South | 500 | Urticaria | EQ-5D | Pearson’s | r = -0.545 p <0.001 | 2* | |||

| Zhao 2022(204) | China | 325 | Urticaria | Chronic urticaria quality of life questionnaire (CU-Q2oL) | Spearman’s | r = 0.769, p <0.001 | 1* | |||

| Koszoru 2023(205) | Hungary | 218 | Atopic dermatitis | EQ5D, Skindex-16 | Spearman’s | EQ-5D-3L rs = 0.267 to 0.570 by EQ5D item; EQ-5D-5L rs = 0.354 to 0.670 by EQ5D item; EQ-5D-3L index rs = −0.669; EQ-5D-5L rs =− 0.731; Skindex-16 rs= − 0.622 | EQ-5D-3L 2* EQ-5D-5L 2* EQ-5D Index 2* Skindex-16 1* |

|||

| Data in this table was extracted from the referenced publications. | ||||||||||

| COSMIN generic hypotheses taken from Table 4 Generic hypotheses to evaluate construct validity and responsiveness (17). Number indicates hypothesis level was supported by correlation, and a * significance at p <0.05. | ||||||||||

| 1. Correlations with (changes in) instruments measuring similar constructs should be ≥ 0.50, | ||||||||||

| 2. Correlations with (changes in) instruments measuring related, but dissimilar constructs should be lower, i.e., 0.30–0.50, | ||||||||||

| 3. Correlations with (changes in) instruments measuring unrelated constructs should be < 0.30, | ||||||||||

| 4. Correlations with (changes in) instruments measuring similar constructs should differ by a minimum of 0.10 from correlations, with (changes in) instruments measuring related but dissimilar constructs, | ||||||||||

| 5. Correlations with (changes in) instruments measuring related but dissimilar constructs should differ by a minimum of 0.10 from correlations with (changes in) instruments measuring unrelated constructs, | ||||||||||

| 6. Meaningful changes between relevant (sub)groups (e.g., patients with expected high versus low levels of the construct of interest). * indicates statistically significant correlation at p <0.05. | ||||||||||

Studies assessing the Differential Item Functioning (DIF) of the Dermatology Life Quality Index

Limited or no DIF was observed over gender or age, but many studies found DIF in some items (Table SID), as is generally found in most health-related QoL measures (29). Significantly, the study of Tan 2022 (30) reported that no significant differences were observed in DLQI scores in 723 acne patients across six countries in Europe, north America and Brazil.

Translations and cross-cultural adaptations

Thirteen publications that addressed validation of translations and cross-cultural adpatations included adaptation to 11 languages from the original English version, one illustrated version, and one considering dimensionality across language versions were included in this study (Table SI(€)).

Appraisal of representation of minorities ethnic participants.

The results of analysis of patients included in studies by Naicker’s Critically Appraisal Tool are shown in Table V.

| Question | Yes | No | Unclear | N/A | Total |

| Were minoritised ethnic participants recruited | 31 (15%) | 3 (1.4%) | 172 (83.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 207 (100%) |

| Were minoritised ethnic participants representative? | 15 (7.2%) | 1 (0.5%) | 189 (93.1%) | 2 (1%) | 207 (100%) |

| Were results data stratified by race/ethnicity and if so, was this justified/appropriate/explained by the author? | 8 (3.9%) | 199 (96.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (1%) | 207 (100%) |

| Were any differences in study outcomes for minoritised ethnic populations appropriately addressed and interpreted? | 6 (2.9%) | 201 (97.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 207 (100%) |

| Did researchers avoid assigning race as a variable, a risk factor or a proxy for genetic ancestry? | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (1.9%) | 201 (97.1%) | 207 (100%) |

| Naicker, R (2022) (23) Critically Appraising for Antiracism Tool. Available at: https://www.criticallyappraisingantiracism.org/. | |||||

Risk of bias

Data for the COSMIN criteria for good measurement properties are given in the Appendix S1 and individual COSMIN ratings are given in the last column of most tables.

Floor and ceiling effects

Two studies reported floor effects (31, 32), one study reported neither (33) and none reported ceiling effects.

Dermatology Life Quality Scores

There were 152 datasets for patients with a dermatological diagnosis where mean DLQI was reported. Additionally, six datasets were reported from healthy control groups (1, 34, 35, 143, 159). More details are given in Table SI(F).

Interpretability or clinical meaningfulness of the scores

The clinical meaningfulness of the DLQI is interpreted using validated score bands with band 0 DLQI scores 0–1 no effect on patient’s life, band 1 DLQI scores 2–5 small effect on patient’s life, band 2 DLQI scores 6–10 moderate effect on patient’s life, band 3 DLQI scores 11–20 very large effect on patient’s life, band 4 DLQI scores 21–30 extremely large effect on patient’s life (206). Narang et al. (164) interpreted their data using banding of the DLQI scores accordingly, and found that superficial cutaneous dermatophytosis had a small effect on the QoL of 41.3% of patients (band 2–5), while it caused an extremely large effect in the lives of 23.9% patients (band 21–30). Shakiar et al. 2006 (53) derived estimates of the MID of the DLQI using both the PASI and the Physician Global Assessment (PGA), as well as two distributional approaches to derive estimates of the MID of the DLQI. Their estimates ranged from 2.33–6.95, but they considered the PASI 50 is too conservative for estimating the minimum change that was beneficial to patients. Further information determining estimates of MID of the DLQI is reported by Basra et al. (85).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review compiles data from 207 peer reviewed studies describing research on 58,828 patients across 49 different countries on the validation of the DLQI over the 27 years of its global use. In contrast, the previous (non-systematic) review (7) of DLQI validation reported on only 115 studies, some of which were not published in English. Others were not full peer-reviewed papers.

The DLQI demonstrated strong test–retest reliability, assessed over 13 studies, reassuring researchers that completion is non-random and consistent. In 43 studies good internal consistency was confirmed, informing researchers of high correlation among the DLQI item scores. Furthermore, the DLQI score change in longitudinal design has been demonstrated in vast numbers of studies, including in randomised controlled trials (2). In addition, this review identified 12 studies performed using anchors to assess change responsiveness, with a range of effect sizes from small to large. Significant responsiveness by ANOVA and Wilcoxon 2-sample (paired) analysis was also demonstrated. Researchers can be confident of the DLQI responding appropriately to change. Concerning responsiveness of the DLQI, patients’ feelings about and perception of their skin disease may change less rapidly than the physical state of their disease. The psychosocial impact of skin disease may persist despite improvement in the disease.

Known-groups validity (207) was tested in 42 studies: such evidence is essential to provide confidence in the construct and use of a measure. The DLQI demonstrates this over a wide variety of groups, including disease severity, anxiety, depression, stigma, scarring, well-being, sexual function, disease location, disease duration and race. Correlation of the DLQI with other 119 different PRO/QoL measures in 207 studies were found in our current review, and demonstrated a range of correlations with other measures, adding to DLQI construct validation. This wide range reflected differences between the DLQI construct and that of comparator measures.

There are currently more than 138 DLQI language translations (208), all based on the original English language measure. Multiple publications demonstrate widespread DLQI use across many of these languages. Translations are all validated by independent forward and backward translations, checked by Cardiff University. Many have been fully culturally validated. This review found twelve publications that investigated DLQI translation validation and cross-cultural adaptations.