ORIGINAL REPORT

Patient Preferences and Cosmetic Outcomes Following Destructive Treatments for Non-facial Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Mixed Methods Study

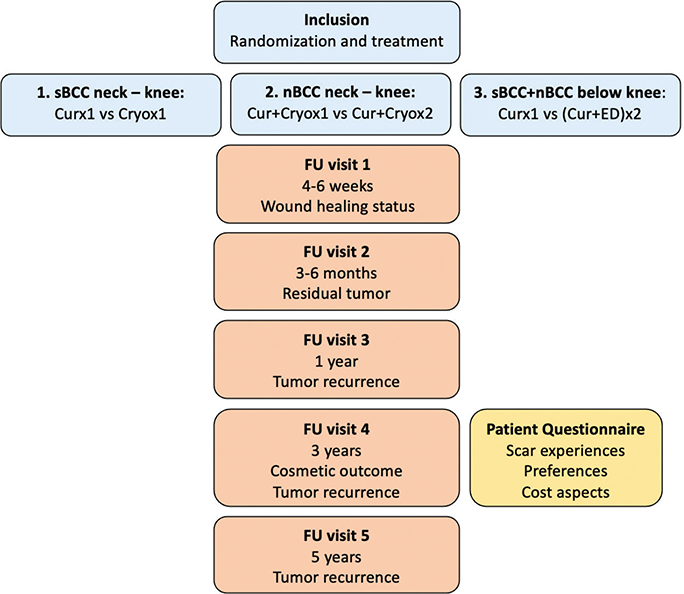

Eva BACKMAN1,2, 1Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, 2Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Gothenburg, 3Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, and 4Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine/Pain Centre, Gothenburg, Sweden The high prevalence of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) entails a substantial burden on healthcare systems. Interest in non-surgical treatment methods for low-risk BCCs, including destructive treatments, is increasing. Dermatologists often highlight suboptimal cosmetic outcomes as drawbacks of destructive treatments, also for non-facial lesions. Patient perspectives regarding scarring and cosmetic outcomes in relation to other relevant factors are largely unknown, yet important to consider in shared decision-making when choosing treatment. This study investigates patient perceptions of scarring following destructive treatments and explores important factors in treatment decisions for non-facial BCCs. Through a mixed-methods design, cosmetic outcomes, patient satisfaction, scarring concerns, and treatment preferences were evaluated within an ongoing randomized clinical trial on destructive treatments for low-risk BCCs. Overall, 157 patients with 425 non-facial scars were assessed. Most patients were not concerned about scar appearance, highlighting a discrepancy compared with dermatologists’ general concerns regarding inferior cosmetic outcome. Instead, when opting for specific treatments, patients listed clearance rates as the most important factor, followed by convenience and time consumption. We believe the results are important both in the context of patient-centred care and in “choosing wisely” when deciding between BCC treatments. Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) significantly impact healthcare costs due to high prevalence. Non-surgical treatments, including destructive treatments, for low-risk basal cell carcinomas are gaining popularity. Yet, patient perspectives on scarring and treatment preferences remain underexplored. This study reveals that patients with non-facial basal cell carcinomas prioritize treatment effectiveness, convenience, and time consumption over scarring concerns. Evaluating 157 patients with 425 non-facial scars, the absolute majority of patients were satisfied with cosmetic outcomes despite dermatologists’ general concerns regarding inferior cosmetic outcome. This underscores the importance of aligning treatment decisions with patient preferences, promoting patient-centred care and shared decision-making in basal cell carcinoma management. Key words: basal cell carcinoma; cryosurgery; curettage; patient preference; patient satisfaction; treatment outcome. Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2025; 105: adv41325. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v105.41325. Copyright: © 2025 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Submitted: Aug 13, 2024; Accepted after revision: Jan 16, 2025. Published: Feb 12, 2025 Corr: Eva Backman, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gröna stråket 16, SE-413 45 Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: eva.johansson.backman@vgregion.se Competing interests and funding: The study was financed by grants from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils, the ALF-agreement (ALFGBG-728261). Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common tumour among fair-skinned populations. Its diagnosis and treatment add pressure to limited healthcare resources (1–5). Low-risk BCCs, i.e., primary lesions outside the facial area with superficial or nodular growth patterns, make up a substantial proportion of these tumours (6–8). Besides surgery, several treatment options are available for low-risk BCCs (9, 10). These include topical treatments such as 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy (PDT) (11). Additionally, destructive treatments including curettage, electrodesiccation, and cryosurgery are possible options for both superficial and nodular BCCs (12–16). A disadvantage of destructive treatments is scarring, often presenting as a hypopigmented area with or without atrophy or induration. The inferior cosmetic outcome of destructive treatments is often highlighted in comparison with PDT (even for non-facial low-risk lesions) and with surgery (17–19). However, few studies have investigated patient perceptions regarding the resulting scars (i.e., relationships between cosmetic outcome, patient satisfaction, and anatomical site) and little is known about the relevant factors regarding patient treatment preferences (20). The aim of this study was to evaluate the cosmetic outcome and its correlation with patient satisfaction after destructive treatments for non-facial BCCs. Further, the study explored factors of importance to patients when deciding upon treatments, e.g., clearance rate, cosmetic outcome, the time required for treatments, the healing process, and cost considerations associated with different treatments. This investigation is part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on destructive treatments of non-facial low-risk BCCs conducted at the Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden (available at https://www.researchweb.org/is/vgr/project/259511) (13, 16). Patients were recruited between November 2017 and March 2022 and will be followed for 5 years (Fig. 1). Superficial BCCs between the neck and knees were randomized to either curettage alone or cryosurgery in 1 freeze–thaw cycle, nodular BCCs between the neck and knees were randomized to curettage followed by 1 or 2 freeze–thaw cycles, and finally superficial and nodular BCCs below the knees were randomized to either curettage alone or curettage plus electrodesiccation repeated twice. This study on cosmetic outcome and patient preferences has a mixed-methods design (21). All patients who had attended their 3-year follow-up visit in the RCT were eligible to participate in the study. At the 3-year follow-up, both the patient and the dermatologist assessed the cosmetic outcome. Patients also completed a survey regarding their perspectives on their scars, previous BCC treatments, treatment preferences, and cost considerations in a tax-funded healthcare system. This was a written questionnaire, posted via mail to all patients who had completed their 3-year follow-up. Quantitative data constitute the predominant part of the analysis, while qualitative data have a supporting role to provide depth of understanding (21). Quantitative assessment of cosmetic outcome (ACO). Scars were evaluated by the patient and the dermatologist using a numeric rating scale (NRS), ranging from 1–10, developed within the research group (Appendix S1). Initially, we considered using the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS, version 2 [in Swedish]) (22). However, a previous report concluded that the reproducibility was lower than expected for non-surgical scars following BCC treatments (23). Further, when we performed pilot testing of the Patient Scar Assessment Scale (PSAS), we concluded that it was too comprehensive and, most importantly, failed to address our research questions regarding patient satisfaction and concerns about scarring. All patients who had attended their 3-year follow-up visit as of 13 February 2023, completed the ACO (n = 157). A research nurse invited patients to rate their scar(s) from 1 to 10 using the following 3 questions: A dermatologist (1 of 7 involved in the study treatment and /or follow-up visits) rated the scars by 3 different parameters (vascularity, pigmentation, and thickness) and provided their overall opinion of each scar using a scale from 1 to 10 (1, normal skin; 10, worst scar imaginable). Questionnaire on patients’ perspectives on scars, treatments, preferences, and cost (STPC). A questionnaire with 14 open- and closed-ended questions (Q1–14) was designed to gain insights on patients’ perspectives on scars, experiences from earlier treatments, treatment preferences, and cost considerations. The questionnaire (Appendix S2) covered 6 main areas: The questionnaire was reviewed within the research group, which included a senior researcher with experience in qualitative research (BH) and underwent pilot testing with 2 patients to ensure that the questions were understandable and relevant. The questionnaire was distributed to eligible patients in the RCT who had completed or were scheduled for their 3-year follow-up before 1 March 2023, and remained enrolled in the study (n = 155). The patients received the questionnaire by mail, and non-respondents were sent a reminder after 3 weeks. Data collection occurred from 1 February to 17 April 2023. Quantitative data from the ACO questionnaire and certain sections of the STPC questionnaire were analysed to generate descriptive statistics. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Kruskal–Wallis test, and Fisher’s exact test were used to test for significant differences between groups. The presence of correlations between satisfaction, concern for the scar, sex, and age was explored using the Spearman correlation test. The significance level was set at p < 0.05, and all tests were two-sided. Statistical calculations were performed using R, version 3.5.3. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For the free-text answers from the STPC questionnaire, verbatim responses were transferred to a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) file. Quantitative and qualitative content analyses were conducted according to Krippendorff’s methodology (24). The answers were inductively coded and categorized by their manifest content. This part was conducted by EB and was subsequently reviewed by BH. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was achieved. Overall, 157 patients with 425 scars were included in the ACO analysis. The majority of patients were male (n = 96, 61.1%) and males had a higher proportion of scars (n = 299, 70.4%). The median age at study inclusion was 70.2 years, with females being slightly younger than males (Table I). , Birgit HECKEMANN3,4

, Birgit HECKEMANN3,4 , Martin GILLSTEDT1,2

, Martin GILLSTEDT1,2 , Sam POLESIE1,2

, Sam POLESIE1,2 and John PAOLI1,2

and John PAOLI1,2

SIGNIFICANCE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.INTRODUCTION

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Context

Fig. 1. Overview of the randomized controlled trial with performed procedures/evaluations. Cur: curettage; cryo: cryosurgery; ED: electrodesiccation; FU: follow-up visit; nBCC: BCC with nodular features; sBCC: superficial BCC; vs: versus.Study design, setting, and participants

Tools and data collection

Statistical analysis

RESULTS

Demographics

The STPC questionnaire was distributed to 155 patients and 135 were returned, yielding a response rate of 87.1%. All questionnaires were included in the analysis, regardless of whether they were fully or partly completed. The median age of the respondents at the time of questionnaire completion was 74.8 years (range 34.5–91.5 years) with 59.3% (n = 80) being male. The total number of scars represented was 372. Among 130 respondents, 49% (n = 64, missing data n = 5) had prior experience with alternative treatments for BCCs, including PDT, surgery (traditional or Mohs surgery), other destructive treatments, and imiquimod.

Quantitative assessments of scars (ACO)

Cosmetic outcome: patient and dermatologist rating. For the majority of scars (n = 341, 82.6%), patients reported that they did not care at all about the appearance of their scars (NRS 1–2), with a mean overall NRS score of 1.7. Further, patients’ overall satisfaction with their scars was high, with a mean NRS score of 2.2. The mean NRS score for the overall opinion of the scars compared with normal skin was 3.6 (more different from normal skin), indicating that the evaluation of scar cosmesis was not consistent with their satisfaction with the scars. The dermatologist’s rating of the overall opinion of the scars compared with normal skin was in the same range as the ratings of patients, with a mean NRS score of 3.1 (Table II).

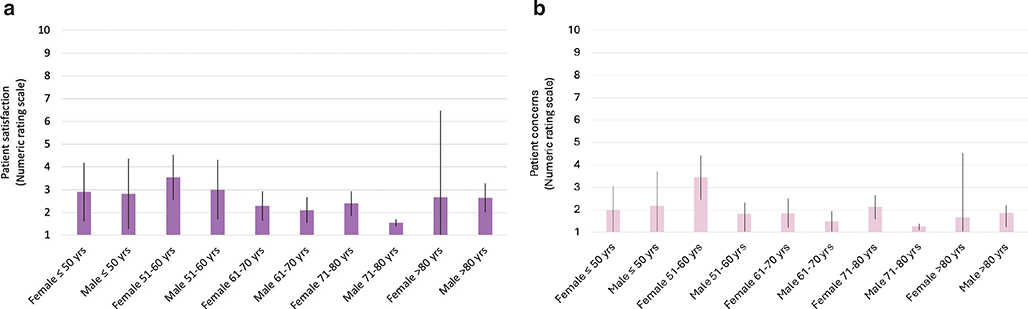

Differences in satisfaction and concern about scars between sex and age groups. Male patients cared slightly less about their scars than female patients, with a mean NRS score of 1.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3–1.6) vs 2.3 (95% CI 1.9–2.7) (p < 0.0001). Male patients were also slightly more satisfied than female patients with a mean NRS score of 2.0 (95% CI 1.8–2–2) vs 2.6 (95% CI 2.3–3.0) (p < 0.0001) (Table SI). Furthermore, there was a trend (not significant) indicating that males in the age group of 71 to 80 years, who had the majority of assessed scars, were more satisfied and also cared less about the appearance of their scars than males and females in other age groups. Females in the age group 51 to 60 years reported being less satisfied and were more concerned about their scars (not significant) (Fig. 2). There were no statistically significant differences in patients’ overall satisfaction with scar appearance following the different destructive treatment protocols (p = 0.44) nor for anatomical sites (p = 0.081).

Fig. 2. (A) Patient satisfaction with the scars and (B) patient concerns about the scars (mean and 95% confidence interval), stratified by sex and age groups. Lower scores indicate a more positive evaluation of the scars.

Qualitative evaluation (STPC questionnaire)

Experience and satisfaction with scars (STPC areas 1–3). When asked about their experiences with their scars and what factors influenced their experiences, 95.6% (n = 129) of patients reported having no problems or hardly ever thinking about their scars in everyday life. Five female respondents reported dissatisfaction with having a hypopigmented scar, due to its location on the chest (n = 3) or on the lower leg (n = 2), while one male had developed an itchy keloid on the shoulder.

The majority (n = 111, 84.1%) did not feel that their experiences had changed over time, while 13 respondents (9.8%) felt they cared less over time, as the scars had become less visible. One respondent (0.76%) reported caring more after 3 years than initially after treatment when she was above all satisfied with having the BCC removed. Another 7 respondents (5.3%) were unsure and 3 did not reply (Table III).

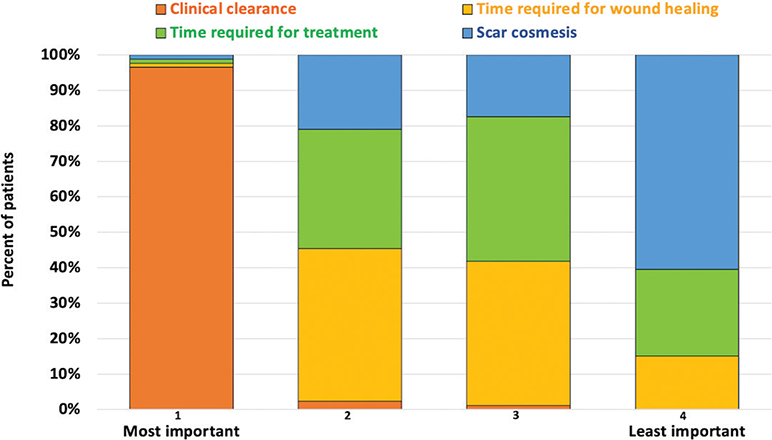

Important factors when choosing a treatment method (STPC areas 4–5). In total, 86 patients (63.4%) gave complete answers when asked to rank the factors of greatest (1) to least (4) importance to them when treating a BCC. The results based on all complete answers (1 to 4) are presented in Fig. 3 and illustrate that the clearance rate was of the greatest importance for the majority of respondents (96.5%), while scar cosmesis was of the least importance. Time required for treatment as well as time required for wound healing ranked as being of intermediate importance. Another 37 patients (27.4%) gave incomplete answers. Among the 123 patients who gave either complete or incomplete answers, 118 (95.9%) rated the clearance rate as the most important factor.

Fig. 3. Patients’ ranking of factors of importance when choosing treatment methods for basal cell carcinoma. 1, most important; 2, second most important; 3, third most important; 4, least important.

When asked specifically about a hypothetical future treatment preference for sBCC (see Appendix S2), 91.7% (n = 110) favoured destructive treatment, while 8.3% (n = 10) preferred PDT or imiquimod to avoid scarring despite a higher risk of recurrence (15 patients did not respond). Patient sex (p = 0.71) and previous experience of BCC treatments (p = 0.094) showed no significant association with treatment preferences.

Cost aspects for treatments in a tax-funded healthcare system (STPC area 6). Of 109 respondents, 50% (n = 55) expressed the view that a patient’s own preference should be prioritized over the cost of the treatment, while 31% (n = 34) thought the cost should be considered to a great extent. The remaining 18% (n = 20) thought that costs should not be considered.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that dermatologist and patient assessments of cosmetic outcome do not necessarily correlate with patient satisfaction. Most respondents expressed negligible concern regarding the resulting scars and instead considered the anticipated effectiveness to be the most important factor when choosing among various available treatment methods for non-facial BCCs. In fact, most patients ranked the cosmetic outcome as the least important factor, below not only the effectiveness but also treatment convenience indicators.

Previous studies have predominantly concentrated on the objective assessments of cosmetic outcomes, using quantitative scar assessment scales, and disregarded the connection to patient satisfaction or their level of concern regarding the aesthetic result (17–19, 25). The absence of this correlation has been noted previously (20). However, one publication comparing imiquimod vs surgery commented on the discrepancy between patient and dermatologist evaluations of the cosmetic outcome, with patients expressing more positive ratings (25).

In addition, earlier comparative studies have either focused on facial lesions or a mix of facial and non-facial lesions. This study exclusively examined non-facial lesions, which we consider valuable, as the majority of low-risk BCCs eligible for non-surgical treatments are non-facial (8). It is therefore important to understand the patients’ preferences for these lesions in order to offer patient-centred and cost-effective treatments. It is nevertheless important to acknowledge that some patients prioritize the cosmetic outcome, also in non-facial areas, such as the lower leg and chest, and therefore a broad palette of treatments is of value. In our study, female sex and age < 60 years were associated with more cosmetic concerns.

BCC guidelines recommend non-surgical treatments as second-line treatments for low-risk lesions (26), which are primarily non-facial lesions, as defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines (27). Topical treatments, including PDT, are often presented as superior alternatives to destructive treatments due to its better cosmesis, but this could be questioned when recurrence rates, costs, and treatment convenience including pain are considered.

In a recent study by Gordon et al., on health-related quality of life in patients with keratinocyte cancer (both facial and non-facial lesions), the lowest impact on quality of life was reported for “appearance” (0.3 on a scale from 0–3), also indicating that the cosmetic concerns are low in general (28). The same study reported slightly higher scores for “worries”, which can imply a greater concern for treatment effectiveness as well as the treatment procedure itself. Also, in a discrete choice study by Essers et al. on topical treatments for superficial BCCs, the anticipated effectiveness of the treatment was the most important factor to the patient (29).

Further, a recent review on cost-conscious treatment approaches for BCCs concluded that for low-risk superficial BCC and nodular BCC, the cost of destructive treatments is 50–60% less compared with PDT or treatment with imiquimod (30). In the same way, Gordon et al. concluded that the costs will be a more important outcome when the cost-effectiveness of interventions is concerned, as keratinocyte cancers’ effect on quality of life and survival may be very small when different treatments are compared (28).

In Sweden, all treatments (including surgery, PDT, destructive treatments, and topical treatments) are covered by tax funding, limiting patient costs to 30 euros per visit, with additional costs for prescription drugs such as imiquimod. When surveyed about cost considerations, half of the patients believed that their own preferences should be prioritized over treatment costs, whereas 31% felt that cost should be a significant consideration. Although not investigated here, patients’ prioritization of cost considerations might differ if they were required to cover a larger proportion of treatment costs themselves. This is an interesting and important area for further research, particularly in countries where patients bear a larger share of treatment costs.

The highest occurrence of BCC is observed in individuals older than 70 years (31), which aligns with the median age of the study population. Some patients mentioned that their perception of scar satisfaction might have differed had they been younger. On the other hand, we have found no research on how patients in different age groups assess the importance of cosmetic outcomes, in relation to other factors, particularly for non-facial lesions. There was a trend towards male patients between 70 and 80 years of age being the most satisfied and the least concerned about scar cosmesis. This may be valuable knowledge as this group constitutes a large proportion of those affected by low-risk non-facial BCCs. There was no significant difference in satisfaction based on the specific type of destructive treatment employed. This finding was surprising, because we initially anticipated that the cosmetic outcome following cryosurgery, which often results in hypopigmentation, would be less favourable compared with curettage alone. However, our results are in line with previous findings by Gordon et al. who reported general low concern about both facial and non-facial lesions.

Limitations

This study has limitations that should be considered. First, as a single-centre study in Sweden, most patients had skin phototypes I to II, potentially showing less visible scarring than those with darker skin. However, we believe the results are applicable to similar patient groups, in other high-incidence areas in Northern Europe, Australia, and the United States. Second, patients accepting to participate in an RCT on destructive treatments may be less concerned about scarring than the general population.

Third, we adopted a mixed-methods design to enhance our understanding of the quantitative scar assessments and to gain insights into patient treatment preferences. While individual interviews and focus groups are the most common methods for collecting patient experiences, we chose questionnaires to obtain a larger volume of responses, aiming for both quantitative and qualitative data. While this approach limited our ability to ask follow-up questions, it allowed feedback from a broader sample. Finally, since the currently validated scar assessment scales (i.e., 4-point scale and POSAS) did not contain the parameters we wished to study, we developed a new patient and physician rating scale, the ACO scale, which has not been externally validated.

Conclusion

This study reveals that patients with non-facial BCCs have low concerns about scarring following destructive treatments. Patients with non-facial BCCs prioritize treatment effectiveness, convenience, and time consumption over cosmesis. These findings highlight the need to align treatment decisions with patient preferences, thereby promoting patient-centred care and shared decision-making in the management of BCC, while also taking cost considerations into account.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank dermatologists Maja Modin, Julia Fougelberg, Anna von Feilitzen, and Hannah Ceder for their assistance during inclusions and follow-up visits and research nurses Alexandra Sjöholm and Eva Wärme for assistance during participants’ study visits. We also acknowledge the use of Chat GTP 3.5 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) for language improvements in the writing process.

IRB approval status: The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (Approval number 743-17, amendment 2022-06983-02) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

REFERENCES

- Lomas A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 1069–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10830.x

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, Barker CA, Mori S, Cordova M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

- Rogers HW, Coldiron BM. Analysis of skin cancer treatment and costs in the United States Medicare population, 1996–2008. Dermatol Surg 2013; 39: 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsu.12024

- Eriksson T TG. Samhällskostnader för hudcancer 2011. Swedish radiation safety authority. Rapportnummer: 2014:49. ISSN: 2000-0456. Available from: www.stralsakerhetsmyndigheten.se

- Noels E, Hollestein L, Luijkx K, Louwman M, de Uyl-de Groot C, van den Bos R, et al. Increasing costs of skin cancer due to increasing incidence and introduction of pharmaceuticals, 2007–2017. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00147. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3463

- Arits AH, Schlangen MH, Nelemans PJ, Kelleners-Smeets NW. Trends in the incidence of basal cell carcinoma by histopathological subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011; 25: 565–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03839.x

- Bernard P, Dupuy A, Sasco A, Brun P, Duru G, Nicoloyannis N, et al. Basal cell carcinomas and actinic keratoses seen in dermatological practice in France: a cross-sectional survey. Dermatology 2008; 216: 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1159/000112925

- Backman E, Oxelblom M, Gillstedt M, Dahlen Gyllencreutz J, Paoli J. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiological impact of clinical versus histopathological diagnosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol Epub 2022, Dec 7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18774

- Altamura D, Menzies SW, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, Soyer HP, Sera F, et al. Dermatoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: morphologic variability of global and local features and accuracy of diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 62: 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2009.05.035

- Work G, Invited R, Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, Moyer J, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 540–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.006

- Arits AH, Mosterd K, Essers BA, Spoorenberg E, Sommer A, De Rooij MJ, et al. Photodynamic therapy versus topical imiquimod versus topical fluorouracil for treatment of superficial basal-cell carcinoma: a single blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 647–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70143-8

- Peikert JM. Prospective trial of curettage and cryosurgery in the management of non-facial, superficial, and minimally invasive basal and squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol 2011; 50: 1135–1138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04969.x

- Backman EJ, Polesie S, Berglund S, Gillstedt M, Sjoholm A, Modin M, et al. Curettage vs. cryosurgery for superficial basal cell carcinoma: a prospective, randomised and controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 1758–1765. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18209

- Nordin P, Larko O, Stenquist B. Five-year results of curettage-cryosurgery of selected large primary basal cell carcinomas on the nose: an alternative treatment in a geographical area underserved by Mohs’ surgery. Br J Dermatol 1997; 136: 180–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb14892.x

- Mallon E, Dawber R. Cryosurgery in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma: assessment of one and two freeze–thaw cycle schedules. Dermatol Surg 1996; 22: 854–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00588.x

- Backman E, Polesie S, Gillstedt M, Sjoholm A, Nerwey A, Paoli J. Curettage plus one or two cycles of cryosurgery for basal cell carcinoma with clinically nodular features: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2023. https://doi.org/1016/j.jaad.2023.04.070

- Wang I, Bendsoe N, Klinteberg CA, Enejder AM, Andersson-Engels S, Svanberg S, et al. Photodynamic therapy vs. cryosurgery of basal cell carcinomas: results of a phase III clinical trial. Br J Dermatol 2001; 144: 832–840. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04141.x

- Basset-Seguin N, Ibbotson SH, Emtestam L, Tarstedt M, Morton C, Maroti M, et al. Topical methyl aminolaevulinate photodynamic therapy versus cryotherapy for superficial basal cell carcinoma: a 5 year randomized trial. Eur J Dermatol 2008; 18: 547–553.

- Thissen MR, Nieman FH, Ideler AH, Berretty PJ, Neumann HA. Cosmetic results of cryosurgery versus surgical excision for primary uncomplicated basal cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Dermatol Surg 2000; 26: 759–764. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.ds00064.x

- Kelleners-Smeets NWJ, Mosterd K, Nelemans PJ. Treatment of low-risk basal cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 539–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.021

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a definition of mixed methods research. J Mixed Methods Res 2007; 1: 112–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298224

- Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, Tuinebreijer WE, Middelkoop E, Kreis RW, et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: a reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004; 113: 1960–1965; discussion 1966–1967. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000122207.28773.56

- Mosterd K, Arits AHMM, Nelemans PJ, Kelleners-Smeets NWJ. Aesthetic evaluation after non-invasive treatment for superficial basal cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013; 27: 647–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04347.x

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Fourth ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2019. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

- Bath-Hextall F, Ozolins M, Armstrong SJ, Colver GB, Perkins W, Miller PSJ, et al. Surgical excision versus imiquimod 5% cream for nodular and superficial basal-cell carcinoma (SINS): a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncology 2014; 15: 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70530-8

- Peris K, Fargnoli MC, Kaufmann R, Arenberger P, Bastholt L, Seguin NB, et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma – update 2023. Eur J Cancer 2023; 192: 113254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113254

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, Alam M, Amini A, Bibee K, et al. Basal cell skin cancer, version 2.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2023; 21: 1181–1203. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.0056

- Gordon LG, Lindsay D, Olsen CM, Whiteman DC. Health utilities and health-related quality of life of patients with keratinocyte skin cancers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol Clin Pract 2023; 2: 983–993. https://doi.org/10.1002/jvc2.227

- Essers BAB, Arits AH, Hendriks MR, Mosterd K, Kelleners-Smeets NW. Patient preferences for the attributes of a noninvasive treatment for superficial basal cell carcinoma: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: e26–e27. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15782

- Patel PV, Pixley JN, Dibble HS, Feldman SR. Recommendations for cost-conscious treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023; 13: 1959–1971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00989-x

- Kappelin J, Green AC, Ingvar A, Ahnlide I, Nielsen K. Incidence and trends of basal cell carcinoma in Sweden: a population-based registry study. Br J Dermatol 2022; 186: 963–969. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20964