QUIZ SECTION

Pruritic Maculopapular Eruption of a 4-month-old Baby: A Quiz

Gustavo ALMEIDA-SILVA1  , Sónia FERNANDES1,2

, Sónia FERNANDES1,2  , Joana ANTUNES1,2

, Joana ANTUNES1,2  , Luís SOARES-ALMEIDA1,2

, Luís SOARES-ALMEIDA1,2  and Paulo FILIPE1–3

and Paulo FILIPE1–3

1Dermatology Department, Unidade Local de Saúde Santa Maria, Lisbon, 2Dermatology University Clinic, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, and 3Dermatology Research Unit, Instituto de Medicina Molecular, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. E-mail: 29711@ulssm.min-saude.pt

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2025; 105: adv42512. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v105.42512.

Copyright: © 2025 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

Published: Feb 10, 2025.

A 4-month-old healthy male patient presented to our Dermatology Emergency Room with a 3-week history of a pruritic skin eruption. There was no history of previous illness or drug introduction, but the mother noted a temporal association between the onset of lesions and the administration of the BCG vaccine. Family history was unremarkable and none of the cohabitants showed similar symptoms.

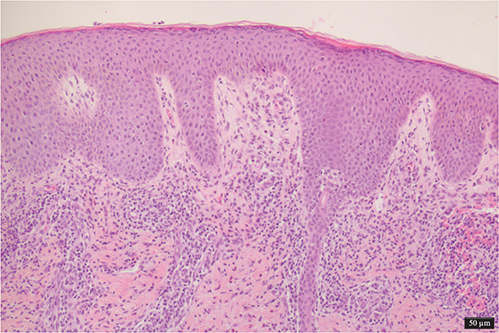

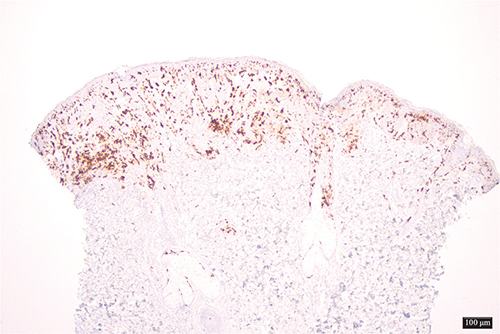

On examination multiple maculopapular lesions, characterized by small slightly raised brownish or reddish macules, papules, and nodules were observed, predominantly on the trunk, and some had a positive Darier sign (Fig. 1). To establish a diagnosis, a skin biopsy was performed on the posterior thorax, revealing a histiocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate in the superficial dermis. The epidermis showed acanthosis, irregular hyperplasia, spongiosis, hypergranulosis, and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated positive staining for CD68, S100, and CD1a (Fig. 3). While awaiting biopsy results, a therapeutic trial with permethrin 5% cream was prescribed, and resulted in clinical resolution of symptoms and lesions.

Fig. 1. Clinical presentation: small slightly raised brownish or reddish macules, papules, and nodules were observed, predominantly on the trunk.

Fig. 2. Histological picture: acanthosis, spongiosis, hypergranulosis, and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis of the epidermis. Histiocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate in the superficial dermis (100x magnification).

Fig. 3. Immunohistochemistry: positive staining for CD1a (40x magnification).

What is your diagnosis?

Differential diagnosis 1: Scabies-induced Langerhans cell hyperplasia

Differential diagnosis 2: Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Differential diagnosis 3: Maculopapular mastocytosis

Differential diagnosis 4: Urticaria

See next page for answer.

ANSWERS TO QUIZ

Pruritic Maculopapular Eruption of a 4-month-old Baby: A Commentary

Diagnosis: Scabies-induced Langerhans cell hyperplasia

Given the initial examination, positive Darier sign, and erythematous macules, papules, and nodules, maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis was initially considered, prompting a skin biopsy. However, the therapeutic response to anti-scabietic therapy, combined with biopsy findings, ultimately supported the diagnosis of scabies-induced Langerhans cell hyperplasia – a rare but documented response in infants.

Histiocytic disorders encompass a diverse group of clonal haematopoietic neoplasms characterized by the proliferation of histiocytes, which are immune cells derived from monocytes. These disorders include Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG), and Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD), among others. The classification of these disorders is continuously evolving, with the World Health Organization (WHO) recognizing distinct entities based on their clinical, histological, and genetic features. The pathogenesis of histiocytic neoplasms is often linked to mutations in key signalling pathways, particularly the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation being a prominent alteration found in LCH and ECD (1–3). Recent studies have highlighted the complexity of these disorders, revealing shared genetic alterations and clonal relationships with other haematologic malignancies, complicating both diagnosis and treatment (4, 5). Scabies, caused by Sarcoptes scabiei, is a very common dermatological condition. Diagnosis is based on an accurate anamnesis, pattern of pruritus, and clinical presentation, which can vary greatly. The mite triggers a robust immune response characterized by the infiltration of Langerhans cells (LCs) in the skin. These dendritic cells play a pivotal role in the skin’s immune defence by capturing and presenting antigens to T lymphocytes, thereby initiating an adaptive immune response. The presence of the mite and its antigens stimulates the proliferation of LCs, leading to hyperplasia, which can mimic Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

The hyperplasia of LCs in response to scabies is primarily driven by the inflammatory milieu induced by the infestation. The mites induce a Th2-type immune response, characterized by the production of cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13, which promote the differentiation and proliferation of LCs. This response is further exacerbated by the presence of eosinophils and other inflammatory cells, which are commonly observed in scabies lesions. Histological examination of affected skin typically reveals a dense infiltrate of CD1a+ and S100+ LCs, confirming the diagnosis of hyperplasia rather than a neoplastic process. Previous reports have documented similar cases of scabies-associated Langerhans cell hyperplasia, underscoring the rarity of such presentations in infants. For instance, Bhattacharjee and Glusac described a series of cases in which infants with scabies exhibited florid Langerhans cell hyperplasia, often misdiagnosed as LCH due to the histological similarities. These findings underline the importance of accurately differentiating clinical and histopathological features that distinguish scabies-induced hyperplasia from true histiocytosis (6, 7).

The first case reporting a misdiagnosis of scabies as LCH was published by Aterman et al. (8) in 1976, and since then several additional cases have been reported. Thorough clinical history and family history is mandatory to avoid unnecessary treatment, as there have been reports of infants receiving chemotherapy due to this misdiagnosis (9–11).

In conclusion, the case of scabies-induced Langerhans cell hyperplasia in this infant illustrates the complex interplay between parasitic infection and immune response. The mechanisms driving this hyperplasia involve a Th2-skewed immune response, leading to the proliferation of LCs and subsequent histological changes that can mimic more serious conditions. The rarity of such cases warrants further investigation and awareness among healthcare providers to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

REFERENCES

- Gulati N, Allen CE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Version 2021. Hematol Oncol 2021; 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2857

- Diamond EL, Durham BH, Haroche J, Yao Z, Ma J, Parikh SA, et al. Diverse and targetable kinase alterations drive histiocytic neoplasms. Cancer Discov 2016; 6: 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0913

- Jain P, Surrey LF, Straka J, Russo P, Womer R, Li MM, et al. BRAF fusions in pediatric histiocytic neoplasms define distinct therapeutic responsiveness to RAF paradox breakers. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2021; 68. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28933

- Tian X, Xu J, Fletcher C, Hornick JL, Dorfman DM. Expression of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) protein in histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms with evidence for p-ERK1/2-related, but not MYC- or p-STAT3-related cell signaling. Mod Pathol 2018; 31: 553–561. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.174

- Kemps PG, Kester L, Scheijde-Vermeulen MA, van Noesel CJM, Verdijk RM, Diepstra A, et al. Demographics and additional haematologic cancers of patients with histiocytic/dendritic cell neoplasms. Histopathology 2024; 84: 837–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.15127

- Bhattacharjee P, Glusac EJ. Langerhans cell hyperplasia in scabies: a mimic of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cutan Pathol 2007; 34: 716–720. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00723.x

- Burch JM, Krol A, Weston WL. Sarcoptes scabiei infestation misdiagnosed and treated as Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol 2004; 21: 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21113.x

- Aterman K, Krause VW, Ross JB. Scabies masquerading as Letterer Siwe’s disease. Can Med Assoc J 1976; 115: 443–444.

- Yang YS, Byun YS, Kim JH, Kim HO, Park CW. Infantile scabies masquerading as Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Ann Dermatol 2015; 27: 349. https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2015.27.3.349

- Yuan M, Pan H, Cui B, Pan J, Ruan Z, Chen Y, et al. Infantile scabies misdiagnosed and treated as Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024; 38: e158–e161. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.19509

- Talanin NY, Smith SS, Shelley ED, Moores WB. Cutaneous histiocytosis with Langerhans cell features induced by scabies: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol 1994; 11: 327–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1470.1994.tb00098.x