Alopecia areata is a common skin disease which is associated with psychosocial and financial burden. No curative therapy exists and, hence, affected persons resort to self-financed cosmetic solutions. However, studies on the economic impact of alopecia areata on individuals are limited. To estimate annual individual out-of-pocket costs in persons with alopecia areata, a cross-sectional study using a standardized online questionnaire was performed in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. A total of 346 individuals (95.1% women, mean age: 38.5 ± 11.6 years) with alopecia areata participated between April and August 2020. Mean additional spending on everyday necessities was 1,248€ per person per year, which was significantly influenced by the duration of the illness, the treatment provider, and disease severity. Hair replacement products and cosmetics accounted for the highest monthly costs, followed by costs for physician visits, hospital treatments, and medication. Most participants (n = 255, 73.7%) were currently not undergoing treatment, due to lack of efficacy, side-effects, costs and acceptance of the disease. Sex differences in expenses were observed, with women having higher expenditures. Alopecia areata-related out-of-pocket costs place a considerable financial burden on affected individuals, are higher compared with those of other chronic diseases, and should be considered in economic assessments of the impact of this disease.

Key words: alopecia areata; burden of disease; hair loss; healthcare economics; out-of-pocket costs; treatment provider.

Accepted Nov 9, 2022; Published Jan 4, 2023

Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv00838.

DOI: 10.2340/actadv.v103.4441

Corr: Alexander Zink, Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Technical University of Munich, School of Medicine, Biedersteiner Strasse 29, DE-80802 Munich, Germany. E-mail: alexander.zink@tum.de

SIGNIFICANCE

Alopecia areata is a form of hair loss in which, due to the visibility of the condition, affected persons often face stigmatization, leading them to invest in cosmetic solutions to hide their condition. This study, which involved 346 people with alopecia areata living in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, found that each affected person spends a mean of 1,248€ per year on necessities related to alopecia areata. This amount is not reimbursed by health insurance companies and depends on the severity of the disease, the duration of disease, and the treatment provider. It represents a burden that must be taken into account in assessments of individuals with alopecia areata.

INTRODUCTION

Hair loss is a widespread condition and a non-specific symptom associated with many diseases, the most common form being androgenetic alopecia (AGA). Hair loss can also occur as traction alopecia, as a symptom of infectious diseases, such as tinea capitis, and can be drug- or chemotherapy-induced (1). After AGA, the second-most frequently occurring non-scarring alopecia is alopecia areata (AA), an autoimmune disease with an estimated worldwide cumulative lifetime incidence of 2% (2–4). AA is distributed equally between the sexes and has an approximate point prevalence of 0.1–0.2% (2, 3, 5). AA can affect children and adults, but has a peak incidence in young adulthood. It is characterized by round patches of hair loss on the scalp or body. Sub-forms include AA totalis, AA universalis, and ophiasis alopecia (2, 6). AA can be a highly visible skin disease with loss of scalp and facial hair, such as eyebrows and eyelashes, which are crucial to defining facial features (7). Hair can play a considerable role in a person’s identity considering the socio-cultural associations between hair and sexuality, health, and youth (8). In particular women are affected by the stigma associated with AA, as baldness is more common and thereby more socially accepted in men (9–11). Nevertheless, hair loss places affected individuals at a higher risk of stigmatization, depression, anxiety, and reduced quality of life (8, 9, 12, 13). The disease prognosis in AA is unpredictable. Current data suggest that 40–70% of individuals with mild disease recover within 1 year, while the remaining affected persons will stay stable or progress to alopecia totalis or universalis and rarely fully recover (14, 15). The current treatment options for AA include topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids, as well as minoxidil and systematic agents, such as methotrexate. Although novel approaches using JAK inhibitors have shown promising first results, JAK inhibitors are not yet in broad usage (6, 16, 17). A lack of curative treatments means that alternative therapies, nutrition, and concealment methods, such as wigs and cosmetics, become a way for affected individuals to regain a sense of control over their disease and counteract the psychosocial burden induced by AA (12). Despite this, alopecia is often considered a mere cosmetic condition by insurance companies and medical providers. Thus, insurance rarely pays for expenses related to the above-mentioned healthcare aspects, resulting in a cumulative financial burden (12, 18–20). Expenses that are not reimbursed by a national insurer or health service are called out-of-pocket costs. However, data on out-of-pocket costs due to AA in Europe are missing. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the monthly out-of-pocket-costs for individuals with AA in 3 European countries and to identify factors associated with higher costs.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design, setting and participants

This cross-sectional online study was conducted between April and August 2020 in 3 European countries: Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Participants were recruited via regional AA patient support groups (4 support groups in Germany, 1 in Austria, and 1 in Switzerland), which advertised the study in their online newsletters. The largest organization was “Alopecia Areata Deutschland e.V.” with 1,200 members in Germany.

Eligible participants had to be able to complete a German questionnaire, be 18 years or older, and have AA diagnosed by a physician. People with other forms of hair loss were excluded. The questionnaire was accessible via SoSci-survey (21) and participants were included after providing electronic informed consent. The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics commission of the Medical Faculty at the Technical University of Munich (reference: 529/19 S).

Questionnaire

Items to assess the economic burden of the questionnaire were derived from pre-existing validated questionnaires and adapted in a consensus-based procedure among 2 physicians, 2 epidemiologists, a medical student, and a patient representative (22). In addition, the questionnaire was pre-tested among 3 patients with AA and further adapted according to their remarks.

The questionnaire consisted of 4 sections: (i) sociodemographic data, (ii) diagnosis and clinical severity, (iii) current treatment, and (iv) monthly expenses. Relevant demographic and socio-economic factors, such as age, sex, current employment, education, marital status, and country of residence were assessed.

Participants had to indicate whether the physician’s diagnosis was AA or other forms of alopecia and report the disease duration. The self-assessed severity of disease had to be estimated according to the 4 stages of AA: (I) scalp less than 30% affected, (II) scalp more than 30% affected, (III) loss of all scalp hair (AA totalis), and (IV) loss of all body hair (AA universalis) (23).

Furthermore, the current form of treatment was investigated, including whether treatment was provided by a dermatologist, a general practitioner (GP), a naturopath, or no treatment at all. An additional open-ended question assessing other forms of treatment was answered by individuals not undergoing current medical treatment and those treated by a naturopath.

Out-of-pocket costs were measured using a standardized questionnaire investigating quantitative economic variables, such as monthly additional expenditures for daily necessities related to AA as an estimated percentage increase per month. In addition, participants were asked how much they pay out-of-pocket in Euro per month for specified health aspects of AA that are not reimbursed by a health insurance plan or national health service (22). If the participant had another reason for extra expenditure that was not covered by the queried aspects, it could be specified in an open text field under “Other”.

Statistical analysis

Participants’ characteristics and costs were analysed and described using mean values with standard deviations (SD) or median with interquartile ranges (IQR) depending on the respective presence of normality tested via Shapiro–Wilk test. Correlations were calculated using Spearman’s test. Participants were categorized in relation to their disease severity (grade I–IV) and type of treatment (by a dermatologist, a GP, a naturopath, no treatment). To assess differences between 2 groups, Mann–Whitney U test was used, and between more than 2 groups, Kruskal–Wallis test was used with Dunn’s test for post-hoc pairwise comparisons. In addition, a multiple linear regression model was calculated to examine the influence of age, sex, disease duration, severity of illness, and treatment provider on out-of-pocket costs. The assumptions for regression were checked for autocorrelation, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity (Appendix S1). Participants with unrealistic costs, another form of alopecia, or incomplete questionnaires were excluded from analysis.

An inductive approach was used to categorize open-ended questions. Answers were summarized and described in absolute and relative frequencies. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R Development Core Team (Vienna, 2020) R software version 4.0.5 (24).

RESULTS

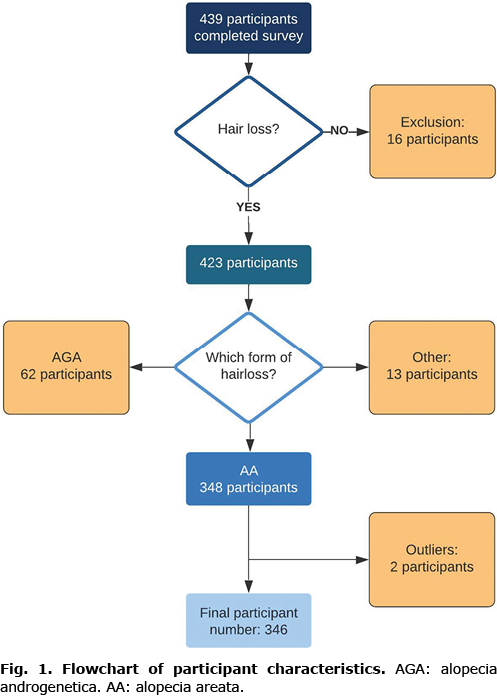

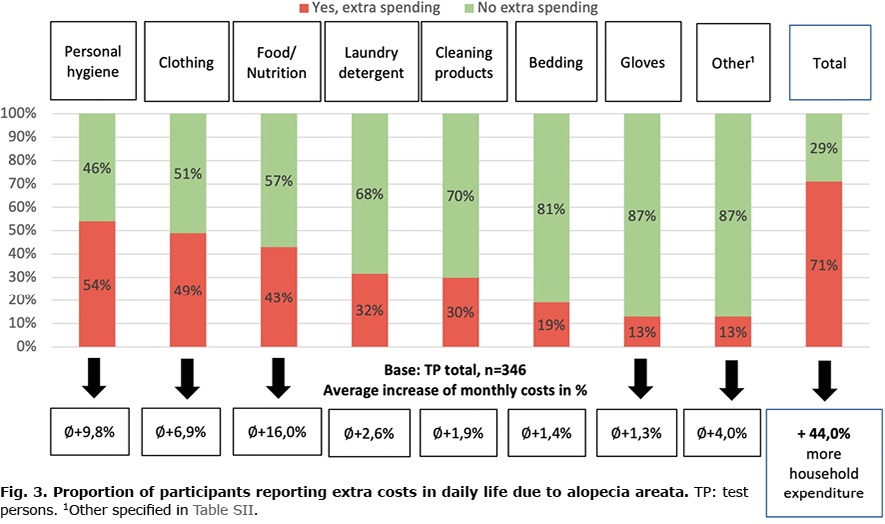

Overall, 1,638 individuals accessed the survey, 634 started the questionnaire, and 439 completed the survey. Of those 439 participants, 16 were excluded because they stated never having experienced hair loss, 62 were excluded because they reported being diagnosed with AGA, and 13 were excluded because they reported having alopecia diffusa or drug-induced alopecia. Two participants were excluded because of implausible values. For example, in 1 case the same unrealistic costs of “200€” was entered for every requested healthcare aspect, resulting in monthly costs of “1,400€”. Overall, data from 346 participants were considered for analysis (Fig. 1). The participants’ mean age was 38.5 ± 11.6 years, with most participants being 30–39 years old (n = 104, 30.1%). The majority of participants were women (n = 329, 95.1%) and employed full-time (n = 236, 68.2%). In total, 303 (87.6%) participants reported being from Germany, 19 (5.5%) from Switzerland, 14 (4.0%) from Austria, and 10 (2.9%) from other countries (Table I). The mean disease duration was 14.5 ± 12.2 years and the most common severity of AA was grade IV alopecia universalis (n = 231, 66.8%, Table I).

Out-of-pocket costs due to alopecia areata

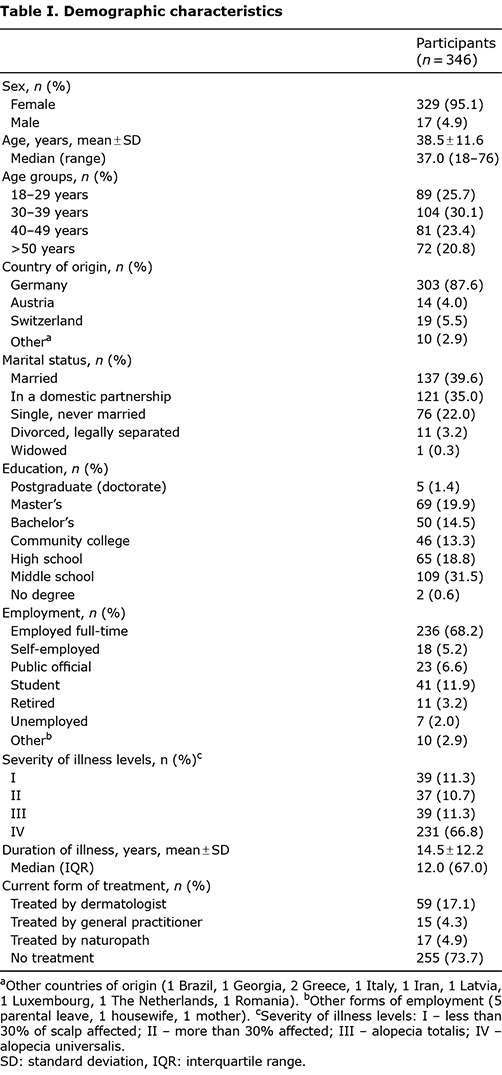

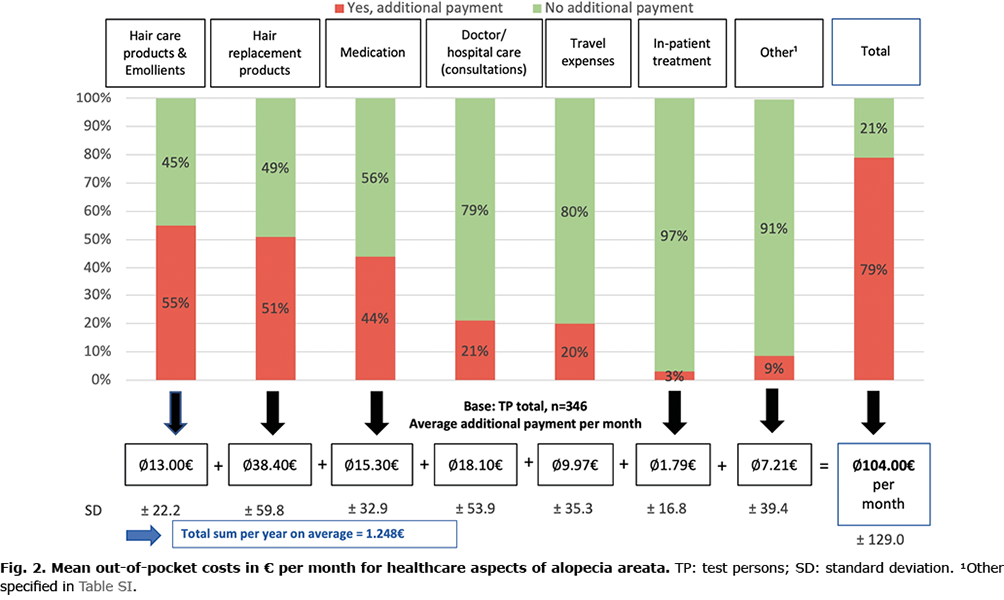

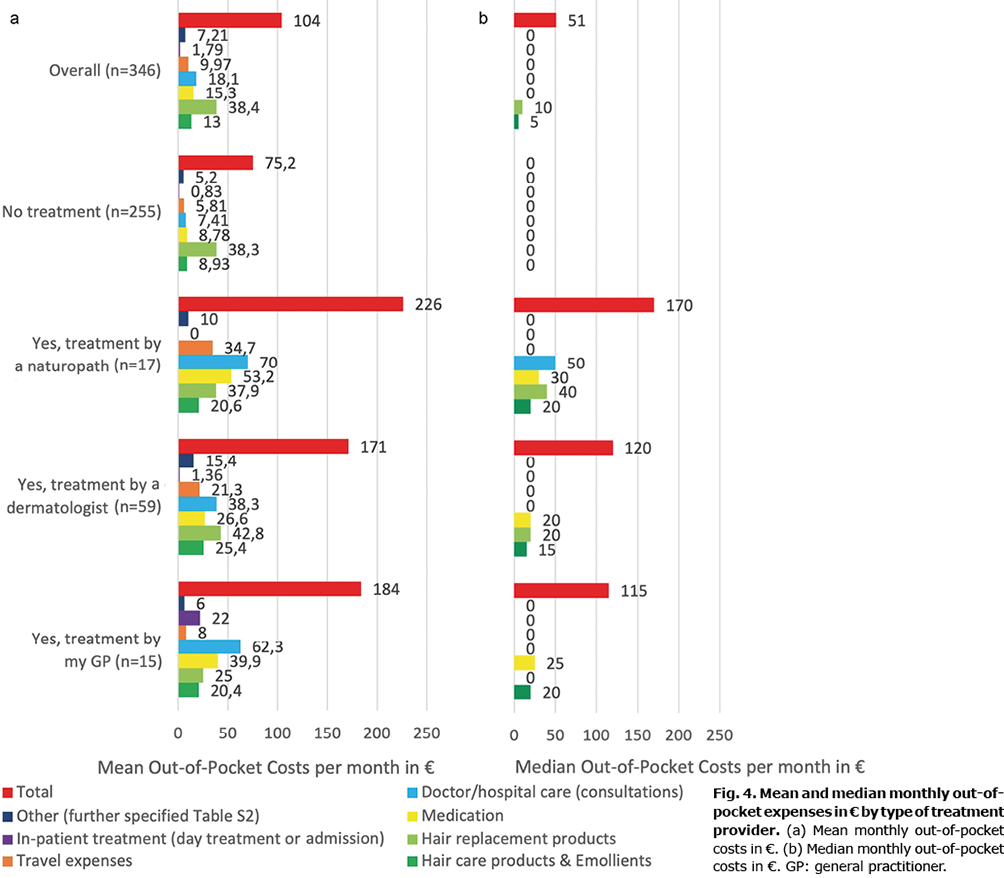

Nearly 80% of participants (n = 273) stated having monthly out-of-pocket-costs due to AA that were not reimbursed by their health insurance. On average, participants had an additional expense of 104.0 ± 129.0€ per month, of which the largest share was spent on hair replacement products and cosmetics (38.4 ± 59.8€) followed by costs for doctor visits and hospital treatments (18.1 ± 53.9€) and medication (15.3 ± 32.9€; Fig. 2). According to answers to open-ended questions, additional expenses were for permanent make-up, nutritional supplements, wig supplies and complementary medicine (Table SI). Extrapolated over 1 year, these costs total 1,248€. More than two-thirds of participants (n = 245, 70.8%) also had additional expenses for everyday necessities. Most participants (n = 148, 42.8%) had a mean of 16.0% additional out-of-pocket-costs for food and nutritional supplements, 9.8% for personal hygiene (n = 168, 48.6%), and 6.9% for clothing (n = 171, 49.4%; Fig. 3). Other expenses (n = 44, 12.7%) were for headwear, special towels, nutritional supplements, and hairdresser visits (Table SII).

Associated factors of out-of-pocket costs

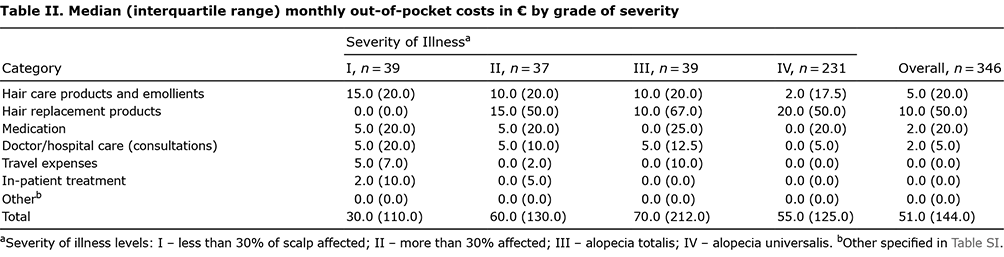

A difference between the sexes regarding additional monthly expenses was observed. The overall monthly out-of-pocket costs were significantly higher for women (median 60.0€, IQR 145.0€) than men (median 10.0€, IQR 20.0€, p = 0.003). Healthcare expenses significantly correlated with a shorter disease duration (correlation coefficient r(344) = –0.19), p < 0.001), and differences in costs were observed regarding the severity of illness. For example, individuals with grade IV AA (median 55.0€, IQR 125.0€) spent less money than those with grade III (median 70.0€, IQR 212.0€, p = 0.04). For participants with the lower grades I (median 30.0€, IQR 110€, p = 0.18) and II (median 60.0€, IQR 130.0€, p = 0.27), expenditures were less than of those with grade IV AA. Medication expenses were, on average, higher in lower disease stages (median 5.0€, IQR 20.0€, p < 0.001), particularly compared with those in grade IV (median 0.0€, IQR 20.0€). However, with higher severity, the monthly expenditures on hair replacement products increased due to greater hair loss (grade I: median 0.0€, IQR 0.0€; grade IV: median 20.0€, IQR 50.0€, p < 0.001, Table II).

The analysis further showed that out-of-pocket expenses were highest among participants treated by naturopaths (median 170.0€, IQR 180.0€, p < 0.001), whereas people without treatment had the lowest out-of-pocket expenses (median 32.0€, IQR 100.0€, p < 0.001). Considering the individual categories that comprise out-of-pocket costs, the different therapy provider categories mainly differ in the expenses for medication, doctor consultations, and travel (Fig. 4a,b). Primarily the costs for consultations were highest among participants treated by a naturopath (median 50.0€, IQR 100.0€, p < 0.001) followed by the expenses of participants treated by a GP (median 0.0€, IQR 62.5€, p = 0.008). In general, costs were significantly higher for participants under any type of treatment than for participants without treatment (Fig. 4a,b; Table SIII, Appendix S2).

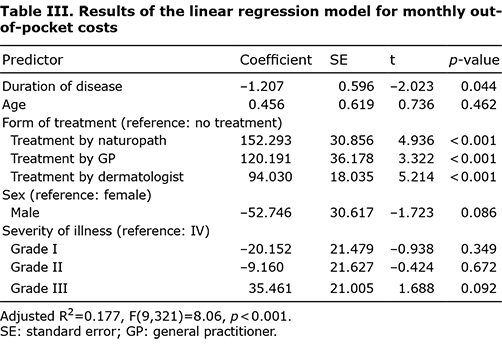

Table III illustrates the results of the multivariate linear regression examining the predictors of monthly out-of-pocket costs due to AA. The type of healthcare provider and the duration of disease had the largest influence on costs. Compared with participants not undergoing treatment, participants being treated by a dermatologist had a mean increase of 94.0€ in additional monthly costs, those treated by a GP of 120.2€, and those treated by a naturopath of 152.3€ (p < 0.001). As the duration of illness increased, the monthly out of pocket costs decreased by 1.2€ per year (p = 0.04). Another negative effect was observed for lower disease severity by comparing grade I (–20.2€, p = 0.35), grade II (–9.2€, p = 0.67) and grade III (35.5€, p = 0.09) to the reference level grade IV.

Current treatment form

Overall, 255 (73.7%) participants reported currently receiving no medical treatment, whereas the remaining participants indicated being treated by a dermatologist (n =59, 17.1%), a naturopath (n =17, 4.9%), or a GP (n =15, 4.3%). To the open-ended question of why an individual was consulting a naturopath, participants stated that no physician could offer help, that prescribed cortisone treatments would not help and only harm instead, and that they had good experiences with alternative, holistic medicine (Table SIV).

The most common reason why participants did not seek medical aid was lack of hope because of no available successful therapy (n = 152, 59.6%). Further reasons were the acceptance of AA (n = 47, 18.4%), a perception of therapy side-effects as being too severe (n = 16, 6.2%), a desire to stop experimenting with treatments (n = 10, 3.9%), and a lack of insurance cover (n = 4, 1.6%).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to investigate the additional monthly expenses of individuals affected by AA and identify associated parameters for higher costs. Almost 80% of all respondents stated having additional monthly expenses. It was found that the mean additional annual expense per individual because of AA was 1,248€. These costs were not reimbursed. Hair replacement products, cosmetics and medication accounted for the largest share of out-of-pocket costs. Furthermore, over two-thirds of respondents stated having additional expenses for daily necessities, such as nutrition, personal hygiene products, and clothing.

Because AA is such a visible condition, the experienced stigma is a driver for expenses for concealment strategies (9, 12). Under German law, wigs are considered durable medical equipment that compensate for disability (25). Nevertheless, insurance companies decide which costs will be reimbursed, which is why claimants often require litigation, thus risking further expenses (25–27).

A previous study among 675 individuals with AA from the USA reported a median out-of-pocket spending of $1,354 annually, primarily on headwear and cosmetic items (28). In another American study, the mean estimated annual out-of-pocket costs were $2,211 for concealment strategies and $1,961 for counselling and therapy (29). Another study investigated the costs of patients with AA for outpatient visits and prescriptions by using insurance claims, indicating that annual out-of-pocket costs regarding AA were $179.35 and costs regarding all comorbidities of patients with AA were $1,175.20 (30). The current study reported slightly lower individual costs, which may result from the inclusion of individuals without health insurance in American studies, who are solely responsible for paying all costs. In contrast to individuals with other chronic diseases, individuals with AA reported higher out-of-pocket costs. Mean annual additional expenses were 927.12€ for individuals with atopic eczema and 224€ for individuals with psoriasis (22, 31). The annual extra expenses due to AA are also higher than those due to rheumatoid arthritis (628€), psoriasis arthritis (412€), and systemic lupus erythematosus (424€) (32, 33). These results, although heterogeneous, underline the financial burden of individuals affected by AA that contributes to the high burden of disease.

The observed sex differences in costs may be related to gendered experiences of living with AA and hair loss in general. Previous studies suggested women may experience more distress about hair loss than men (34–37). This difference could result from women attaching greater importance to their appearance than men do, or that baldness in men being more socially accepted and common (10). Therefore, the expenses for concealing hair loss are lower for men. Nevertheless, the burden of disease for men should not be underestimated and warrants further investigation.

Having a shorter duration of disease, having a more severe disease severity, and being in medical treatment were associated with higher out-of-pocket-costs. The increasing costs were for medication and consultations, while costs for concealment products only increased with higher severity and remained stable in all treatment groups. In addition, the out-of-pocket costs increased with disease severity up to a certain stage (grade III), after which costs decreased. However, the increase in disease severity between stages is not continuous and varies from almost healthy (I/II) to total hair loss (III/IV) (4, 23). No previous studies have explored the choice of healthcare providers for AA treatment.

Most participants in this study were not undergoing treatment. This group had the lowest out-of-pocket expenses compared with those of individuals treated by naturopaths, GPs, and dermatologists (in descending order). Particularly individuals with severe disease, such as the majority in our study, turn away from treatment and rely on concealment strategies and self-treatment with over-the-counter medication and nutritional supplements (7).

The unpredictable course of disease and often disappointing results of treatments meant that participants stated “feeling like a guinea pig” in experimenting with different therapies. They also indicated feelings of hopelessness and financial burden. Some participants, however, mentioned learning to accept the disease by turning their back on treatments. Other qualitative studies confirm the lengthy and difficult path to self-acceptance regarding AA and suggest that hope for regrowth must be abandoned for this to happen (7, 34, 38). Accordingly, the decrease in investment and costs in our study with increasing duration and severity of AA (grade IV) as well as the abandoning of treatment can be understood as a movement towards self-acceptance.

Mesinkovska et al. (29) identified treatment side-effects and lack of efficacy as the most frequently cited reasons for therapy interruption. The more holistic approach of naturopathic medicine was also mentioned in the current study as a reason for turning away from conventional medicine. Dissatisfaction with treatment leads to the use of alternative methods, such as homeopathy, nutritional supplements, and relaxation methods, which was reflected in the current study through the higher out-of-pocket costs associated with alternative therapies (39). There are systematic reviews highlighting the potential efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine in AA in hair growth and improved wellbeing (7, 40, 41). Overall, the choice of treatment provider (dermatologist, GP, or naturopath) had a decisive influence on additional expenditures.

While new therapeutic approaches with JAK inhibitors offer promising results in contrast to established ones, the affordability of these treatments needs to be considered by physicians when recommending them, as they may impose additional financial ramifications (42). As demonstrated in the study, particularly individuals with an intermediate degree of severity (grade III) bear a high financial burden. Therefore, it is important to raise awareness about the financial burden of AA, adding to the already associated stigmatization and psychosocial burden. Moreover, the high number of individuals abandoning medical care needs to be considered when developing public awareness programmes.

Study limitation and strengths

This is the first study assessing out-of-pocket costs due to AA in Europe. Because of the online setting for the study, data from participants without medical treatment were included, which may not have been feasible in a typical medical setting. A limitation, however, is the potential for selection bias, as individuals with severe forms of disease or high expenditures because of their illness may be more likely to participate. Furthermore, a possible recall bias should be mentioned, whereby participants subsequently overestimate their expenses. Another limitation is the predominantly female representation in the study, which was also observed for previous studies (12, 29). Thus, further research is needed to explore the experiences of men with AA and their respective need for support groups, as well as to estimate all pending costs caused by AA, including insurance services.

Conclusion

AA-related out-of-pocket costs place a considerable financial burden on those affected, are higher compared with those other chronic diseases, and should be included in economic assessments of the impact of this disease. The results of this questionnaire emphasize the importance of broader insurance coverage for treatments and supportive coping methods, including hair replacement products and cosmetic camouflage. More awareness of the financial burden of chronic diseases such as AA is needed for affected individuals, insurance companies, and healthcare providers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the following organizations for their support in recruitment for this study: Alopecia Areata Deutschland e.V, Alopecia Areata Schweiz, Alopecia Areata Austria, Kopfsache Berlin, Die vielen Gesichter von Alopecia Areata, and Selbsthilfegruppe Haarausfall München. In addition, the authors would like to thank the respondents for their participation in the survey.

Funding: Technical University of Munich, Department of Dermatology and Allergy.

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics commission of the Medical Faculty at Technical University of Munich (reference: 529/19 S).

Conflicts of interest: MCS has received consultancy/speaker’s honoraria from Novartis, Leo Pharma, Beiersdorf, Janssen Cilag and is currently employed by Novartis Pharma GmbH, Germany. TB has received grants from Celgene-BMS, Lilly, Mylan, Novartis, Sanofi, Regeneron, has served on an advisory board for LEO Pharma, Lilly, Mylan, Sanofi, received consultancy or speaker’s honoraria from Lilly, Mylan, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi and was past-president of the German Society of Dermatology (unpaid). AZ has received unrestricted research grants from Novartis Pharma, Leo Pharma, has received consultancy and speaker’s honoraria from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Beiersdorf Dermo Medical, Bencard Allergie, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GSK, Janssen Cilag, Leo Pharma, Miltenyi Biotec, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Takeda Pharma, UCB Pharma and has held a fiduciary role for the German Society of Dermatology (unpaid).

REFERENCES

- Shapiro J, Wiseman M, Lui H. Practical management of hair loss. Can Fam Physician 2000; 46: 1469–1477.

- Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2015; 8: 397–403.

- Mirzoyev SA, Schrum AG, Davis MDP, Torgerson RR. Lifetime incidence risk of alopecia areata estimated at 2.1% by Rochester Epidemiology Project, 1990–2009. J Invest Dermatol 2014; 134: 1141–1142.

- Pratt CH, King LE, Jr, Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017; 3: 17011.

- Safavi K. Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol 1992; 128: 702.

- Hordinsky MK. Overview of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2013; 16: S13–15.

- Messenger AG, McKillop J, Farrant P, McDonagh AJ, Sladden M. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of alopecia areata 2012. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 916–926.

- Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. BMJ 2005; 331: 951–953.

- Schielein MC, Tizek L, Ziehfreund S, Sommer R, Biedermann T, Zink A. Stigmatization caused by hair loss – a systematic literature review. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020; 18: 1357–1368.

- Quittkat HL, Hartmann AS, Dusing R, Buhlmann U, Vocks S. Body dissatisfaction, importance of appearance, and body appreciation in men and women over the lifespan. Front Psychiatry 2019; 10: 864.

- Cartwright T, Endean N, Porter A. Illness perceptions, coping and quality of life in patients with alopecia. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160: 1034–1039.

- Montgomery K, White C, Thompson A. A mixed methods survey of social anxiety, anxiety, depression and wig use in alopecia. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e015468.

- Burns LJ, Mesinkovska N, Kranz D, Ellison A, Senna MM. Cumulative life course impairment of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology 2014; 12: 197–204.

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, Brinster N, Christiano AM, et al. Alopecia areata: Disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 1–12.

- Tosti A, Bellavista S, Iorizzo M. Alopecia areata: a long term follow-up study of 191 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 438–441.

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, Brinster N, Christiano AM, et al. Alopecia areata: An appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 15–24.

- Phan K, Sebaratnam DF. JAK inhibitors for alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 850–856.

- Marks DH, Penzi LR, Ibler E, Manatis-Lornell A, Hagigeorges D, Yasuda M, et al. The medical and psychosocial associations of alopecia: recognizing hair loss as more than a cosmetic concern. Am J Clin Dermatol 2019; 20: 195–200.

- Korta DZ, Christiano AM, Bergfeld W, Duvic M, Ellison A, Fu J, et al. Alopecia areata is a medical disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 832–834.

- Kalabokes V, Besta RM. The role of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation in the management of alopecia areata. Dermatologic Therapy 2001; 14: 340–344.

- Leiner DJ. SoSci Survey (Version 3.2.35) 2018 [Computer software]. Available from: http://www.soscisurvey.com.

- Zink AGS, Arents B, Fink-Wagner A, Seitz IA, Mensing U, Wettemann N, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for individuals with atopic eczema: a cross-sectional study in nine European countries. Acta Derm Venereol 2019; 99: 263–267.

- Altmeyer P. A. Therapielexikon Dermatologie und Allergologie: Therapie kompakt von A bis Z. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2005: 41.

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020.

- GKV-Spitzenverband. Fortschreibung der Produktgruppe 34 “Haarersatz” des Hilfsmittelverzeichnisses nach § 139 SGB V. 2018, January 15.

- Koblenz S. S9 KR 756/15. juris, Court case 2016, November 16.

- LSG-München. Keine Erstattung von Mehrkosten für eine Perückenversorgung. 2021.

- Li SJ, Mostaghimi A, Tkachenko E, Huang KP. Association of out-of-pocket health care costs and financial burden for patients with alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol 2019; 155: 493–494.

- Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, Ko J, Cassella J. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: a cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2020; 20: S62–S68.

- Senna M, Ko J, Tosti A, Edson-Heredia E, Fenske DC, Ellinwood AK, et al. Alopecia areata treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and comorbidities in the us population using insurance claims. Adv Ther 2021; 38: 4646–4658.

- Jungen D, Augustin M, Langenbruch A, Zander N, Reich K, Stromer K, et al. Cost-of-illness of psoriasis – results of a German cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 174–180.

- Huscher D, Merkesdal S, Thiele K, Zeidler H, Schneider M, Zink A, et al. Cost of illness in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus in Germany. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65: 1175–1183.

- Westhoff G, Listing J, Zink A. [Out-of-pocket medical spending for care in patients with recent onset rheumatoid arthritis]. Z Rheumatol 2004; 63: 414–424.

- Welsh N, Guy A. The lived experience of alopecia areata: a qualitative study. Body Image 2009; 6: 194–200.

- Cash TF, Price VH, Savin RC. Psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia on women: comparisons with balding men and with female control subjects. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 29: 568–575.

- Hoffer L, Achdut N, Shvarts S, Segal-Engelchin D. Gender differences in psychosocial outcomes of hair loss resulting from childhood irradiation for tinea capitis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 7825.

- Gonul M, Cemil BC, Ayvaz HH, Cankurtaran E, Ergin C, Gurel MS. Comparison of quality of life in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol 2018; 93: 651–658.

- Davey L, Clarke V, Jenkinson E. Living with alopecia areata: an online qualitative survey study. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 1377–1389.

- Hussain ST, Mostaghimi A, Barr PJ, Brown JR, Joyce C, Huang KP. Utilization of mental health resources and complementary and alternative therapies for alopecia areata: A U.S. survey. Int J Trichology 2017; 9: 160–164.

- Tkachenko E, Okhovat JP, Manjaly P, Huang KP, Senna MM, Mostaghimi A. Complementary and alternative medicine for alopecia areata: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2023; 88: 131–143.

- van den Biggelaar FJ, Smolders J, Jansen JF. Complementary and alternative medicine in alopecia areata. Am J Clin Dermatol 2010; 11: 11–20.

- Gilhar A, Keren A, Paus R. JAK inhibitors and alopecia areata. Lancet 2019; 393: 318–319.