ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Neuroimmune Mediators of Pruritus in Hispanic Scalp Psoriatic Itch

Leigh A. NATTKEMPER1, Zoe M. LIPMAN1, Giuseppe INGRASCI1, Claudia MALDONADO2, Juan Carlos GARCES2, Enrique LOAYZA2 and Gil YOSIPOVITCH1

1Dr Phillip Frost Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery and Miami Itch Center, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA and 2Departamento de Dermatología, Hospital Luis Vernaza, Guayaquil, Ecuador

Scalp psoriatic itch is a common, bothersome, yet understudied, condition with numerous associated treatment challenges. The aim of this study was to enhance our understanding of the pathophysiology of scalp psoriatic itch. Immunohistochemical analysis of known neuroimmune mediators of pruritus was conducted using scalp biopsies from 27 Hispanic psoriatic patients. Patients were categorized into mild/moderate or severe itch groups according to their itch intensity rating of scalp itch. Protease activated receptor (PAR2), substance P, transient receptor potential (TRP)V3, TRPM8 and interleukin-23 expression all correlated significantly with itch intensity. The pathophysiology of scalp psoriasis is largely non-histaminergic, mediated by PAR2, interleukin-23, transient receptor potential channels, and substance P.

Key words: psoriasis; pruritus; scalp psoriasis.

SIGNIFICANCE

The body region most predominantly impacted by psoriatic itch is the scalp. This study correlated the presence of neuroimmune mediators with severity of itch in patients with scalp psoriasis. The results show that there may be a larger neural component to scalp psoriatic itch than previously thought. Neurotropic agents, rather than anti-histaminergic or cooling agents, may warrant greater consideration for the management of scalp psoriatic itch.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv4463. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.4463.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Jan 11, 2023; Published: Mar 23, 2023

Corr: Gil Yosipovitch, Dr Phillip Frost Department of Dermatology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 1600 NW 10th Ave, RMSB 2023, Miami FL 33136, USA. E-mail: Gyosipovitch@med.miami.edu

Competing interests and funding: The authors thank Karen Veverka, PhD, for funding support of this study.

INTRODUCTION

Pruritus is an often underappreciated and overlooked symptom of psoriasis. However, increasing evidence over the past decade has shown that itch is one of the most prevalent and burdensome symptoms of the disease, affecting approximately 60–90% of patients with psoriasis (1–4). The body region most predominantly impacted by psoriatic itch is the scalp (5, 6). Treatment of scalp psoriatic itch is a challenge, not only due to location of lesions’ inaccessibility to topical treatments, but also due to an incomplete understanding of its pathophysiology (7).

It has been hypothesized previously that the hair follicle plays a central role in psoriatic scalp itch with frequent communication and connections between the neuroimmune, neuroendocrine, and vascular systems (7). We recently studied the itch transcriptome in plaque-type psoriasis and found several cytokines and neuropeptides whose transcription was highly correlated with the severity of psoriatic itch. These neuroimmune entities included interleukin (IL)-17, IL-23, IL-31, transient receptor potential (TRP)V1, TRMP8, TRPV3, and substance P (SP; 8).

In order to improve management and develop more targeted treatments for psoriatic scalp itch, greater understanding of the key mediators of this condition is required. The aim of the current study was to correlate the presence of neuroimmune mediators with severity of itch in patients with scalp psoriasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

As a prospective study, scalp biopsies and clinical data were collected from 27 Caucasian Hispanic patients with psoriasis (51.8% female; mean ± standard deviation [SD] age 40.4 ± 19.3 years) at Hospital Luis Vernaza in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Of these 27 psoriatic patients, 44% had scalp only involvement. At the time of scalp biopsy, none of the patients were treated for their psoriasis or itch, as a washout period was required to enrol in the study. Two patients had a 6-week washout of oral corticosteroids or methotrexate, and 25 patients had a 1-week washout of topical corticosteroids or antifungal. At the time and location of biopsy, patients were asked to rate their average itch intensity for the past 24 h on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS). Patients were categorized into 2 groups based on itch severity: 13 patients were classified as having mild or moderate itch (NRS 0–6), and 14 as severe itch (NRS 7–10). The 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale was utilized to evaluate the severity of the overall scalp psoriasis. Patients categorized as severe itch had a slightly higher (p = 0.0194) scalp IGA than those with less itch, and itch intensity rating correlated with scalp IGA (p = 0.0009, r = 0.6007). Patient demographics and medications are summarized in Table I. Patients’ ages did not significantly differ across the different itch severities via an unpaired t-test.

Immunohistochemistry and quantification

Biopsy samples were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Samples were sectioned on a microtome at 5-μm thickness. Slides were deparaffinized and incubated in an antigen retrieval solution (Dako, Glostrop, Denmark) overnight at 60°C, then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Slides were blocked with 5% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibody in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies included: mouse anti-histamine (1: 500, MAB5408, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA); rabbit anti-NGF (1: 1000, ab6199, Abcam, Cambridge, UK); rabbit anti-IL31 (1: 200, ab102750, Abcam,); mouse anti-CD68 (1: 150, ab955, Abcam); rabbit anti-IL17 (1: 100, ab79056, Abcam); mouse anti-CD3 (1: 20, ab17143, Abcam); rabbit anti-PAR2 (1: 100, sc-5597, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX); guinea pig anti-substance P (SP; 1: 500, ab106291, Abcam); rabbit anti-TRPV1 (1: 100, ab3487, Abcam; mouse anti-β-tubulin (1: 500, catalog # M015013, Neuromics, Edina, MN); rabbit anti-TRPM8 (1: 250, ab3243, Abcam); mouse anti-TRPV3 (1: 500, ab85022, Abcam); rabbit anti-periostin (1: 250, ab14041, Abcam); mouse anti-CGRP (1: 100, ab81887, Abcam); mouse anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNFα) (1: 100 ab220210, Abcam); and rabbit anti-IL23 (1: 50, ab45420, Abcam).

For detection, slides were incubated with corresponding Alexa Fluor 488 & 555 secondary antibodies (1: 300; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. All slides were mounted with Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) to visualize the dermal-epidermal junction. Sections treated without any primary antibodies were used as negative controls. Specificity of each primary antibody was previously confirmed by pre-absorption with its respective blocking peptide.

Complete sections were title-scan imaged at 20× objective magnification using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and analysed in a blinded manner using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). A range of 2–4 complete sections from each human subject were analysed. Epidermal nerve fibre density was measured by dividing the number of β-tubulin + , SP + , or CGRP + nerves crossing the dermal-epidermal junction by the length of the epidermis. Fluorescence intensity (in arbitrary units; AU) was measured in the epidermis excluding stratum corneum and normalized by area and background fluorescence. Periostin deposition was measured by dermal fluorescence intensity (AU) by measuring the dermis below the dermal-epidermal junction and normalized by area and background fluorescence. Positive cell counts were quantified in the area surrounding the dermal-epidermal junction (epidermis, excluding stratum corneum, and into the papillary dermis) and normalized by area.

Statistical analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SD. Unpaired t-test analyses were used to compare differences between psoriatic itch severity groups. Linear regressions and Spearman’s correlations were also performed to correlate itch mediators with itch severity. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Neuropeptides

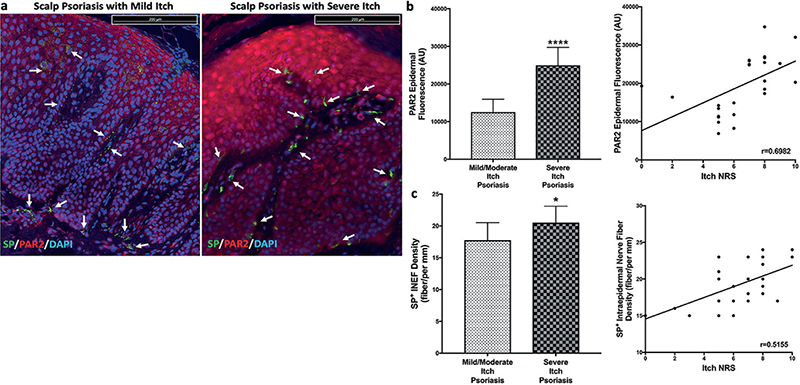

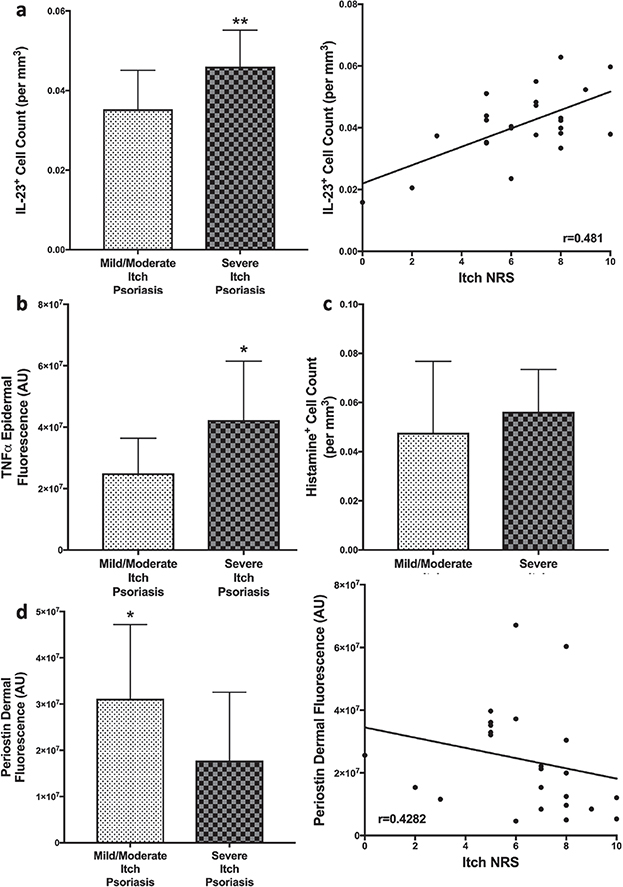

Epidermal expression of protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) was significantly elevated (p < 0.0001) in patients with scalp psoriasis with severe itch compared with those with lower itch intensity. This PAR2 expression also had a significant correlation with itch severity (p = 0.0001, r = 0.6982; Fig. 1a, b). There was no significant difference in histamine + cells in psoriatic scalp itch groups, nor did histamine + cells correlate with itch severity (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 1. Representative images and quantification of immunostaining of protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2) and substance P (SP)+ nerve fibres in psoriatic scalp. (a) Representative images of PAR2 and SP immunostaining for mild itch and severe itch scalp psoriasis lesions. Quantification showed increased epidermal expression of PAR2 (b) and increased SP + nerve density (c) in psoriatic scalp with severe itch, with both correlating with itch severity. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001. All scale bars in images are 200 micron.

Staining for SP revealed a slightly increased expression in the nerves of patients with scalp psoriasis with severe itch compared with mild/moderate itch (p = 0.0152). SP + nerve staining also significantly correlated with itch intensity (p = 0.007, r = 0.5155; Fig. 1a, c). Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) + stained nerves did not reveal any significant difference between groups. Of note, there was also no significant intraepidermal nerve fibre density (IENF) difference between psoriatic scalp itch groups.

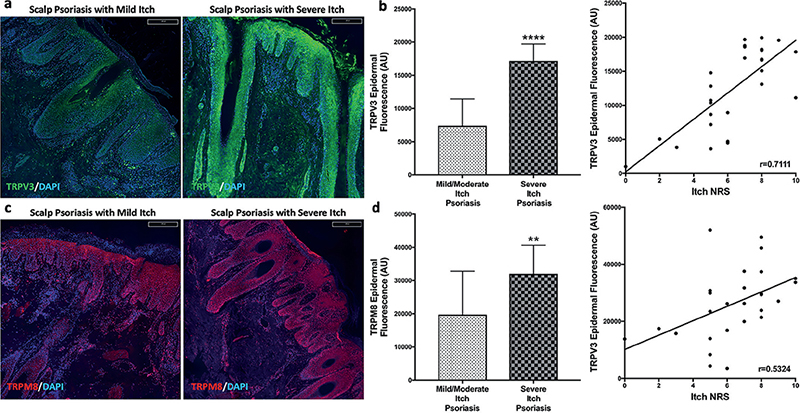

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels

Epidermal expression of TRPV3 was significantly greater (p < 0.0001) in scalp psoriatic patients with severe itch (Fig. 2a) compared with those with mild/moderate itch. Itch severity also correlated with epidermal TRPV3 levels (p < 0.0001, r = 0.7111). TRPM8 had greater (p = 0.0075) epidermal fluorescence in psoriatic scalp of severe itch compared with those with less itch, and this expression correlated with itch intensity (p = 0.0043, r = 0.5324; Fig. 2c, d). Epidermal TRPV1 was not different between scalp psoriasis itch severity groups and did not correlate with itch intensity.

Fig. 2. Representative images and quantification of immunostaining of transient receptor potential (TRP) V3 and TRPM8 in psoriatic scalp. Representative images of TRPV3 (a) and TRPM8 (c) immunostaining for mild itch and severe itch scalp psoriasis lesions. Quantification showed increased epidermal expression of TRPV3 (b) and TRPM8 (d) in psoriatic scalp with severe itch, with both correlating with itch severity. Statistical significance: **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Immune system

IL-23 + cells were increased in severe itch psoriatic scalp (p = 0.0097) compared with less itchy psoriatic scalp, and IL-23 correlated with itch intensity (p = 0.0149, r = 0.481; Fig. 3a). Epidermal TNFα was found to slightly (p = 0.0133) differ in severe itch scalp lesions compared to mild/moderate itch psoriatic lesions, but there was only a trend in correlation with itch intensity (p = 0.0602, r = 0.3891; Fig. 3b). IL-17 and IL-31 fluorescence was not different between itch severity groups and did not correlate with itch intensity.

Fig. 3. Quantification of immunostaining of immune mediators in psoriatic scalp. Immunofluorescent quantification of interleukin (IL)-23 + cells (a) and epidermal tumour necrosis factor (TNF)α (b) showed increased expression in psoriatic scalp with severe itch, with only interleukin (IL)-23 expression correlating with itch severity. While Histamine + cells (c) did not show a difference between psoriatic scalp itch groups. Dermal deposition of periostin (d) was significantly increased in scalp psoriasis with mild/moderate itch and had a negative correlation with itch. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

A marker for macrophages, CD68, and a T cell marker, CD3, did not differ between scalp psoriasis itch groups.

Periostin, an extracellular matrix protein, was found to have elevated dermal deposition in less itchy psoriatic scalp compared with scalp with severe itch (p = 0.0408; Fig. 3d). Dermal deposition of periostin had a weak, but negative, correlation with itch intensity (p = 0.0327, r = –0.4282; Fig. 3d).

DISCUSSION

These results indicate that the aetiology of itch in scalp psoriasis involves a complex interplay of neurogenic and immunogenic inflammation, with the itch being mediated by a non-histaminergic pathway. These findings are consistent with prior data in many types of chronic itch (8, 9).

Activation of PAR2, a G-protein coupled receptor located on sensory nerve endings, epidermal keratinocytes, and at the level of the inner root sheath (IRS) in scalp hair follicle (HF), has been implicated in non-histaminergic itch. When activated, it stimulates the release of SP from nerve fibres and acts synergistically with TRPV1 and TRPV3 channels found at the level of the outer root sheath (ORS) to amplify the itch sensation (10). In the current study, the epidermal expression of PAR2 was significantly increased in scalp psoriasis with severe itch. Interestingly, our previous RNA sequencing study did not show PAR2 mRNA expression to be elevated in itchy psoriasis lesions, although that study did not examine scalp lesions (8). This difference in findings may suggest that there are transcriptomic profile differences between scalp psoriasis itch and itch in other body areas. Further exploration of these differences may provide better understanding of psoriatic scalp itch.

Increased SP + nerve staining in psoriatic lesions not located on the scalp were previously reported to correlate significantly with itch severity (11, 12). The current study confirms these finding in scalp psoriatic lesions, and further confirms that IENF density in psoriasis, including scalp lesions, do not correlate with itch intensity (13). SP is thought to play a role in kick-starting the initial stages of scalp psoriatic itch by binding to neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors (7). Furthermore, serlopitant, a NK-1 inhibitor, demonstrated an anti-pruritic effect in psoriasis in a phase 2 study (14). In addition, SP may activate mast cells via mas-related G-protein coupled receptor X2 (MRGPRX2) to transmit itch in psoriatic lesions (14). It would be of interest to further examine the role of mast cell MRGPRX2 in psoriasis, as it is known that mast cells become overactive in psoriatic lesions (15–17). Since the current results show no correlation with histamine and itch intensity in scalp psoriasis, activation of MRGPRX2 may be the alternative itch signalling pathway independent of histamine release.

TRP channels play a pivotal role in somatosensation, including itch (18). The current study demonstrated that TRPV3 and TRPM8 channels had increased expression in severe itch of scalp psoriatic lesions, which is congruent with our earlier sequencing study, which found significantly increased expression of TRPV3 and TRPM8 mRNA in non-scalp psoriatic lesions (8). TRPV1, which has been shown to be involved in acute itch, did not show correlation with psoriatic scalp itch severity (19). Clinically, studies have shown topical capsaicin, which desensitizes TRPV1 channels and depletes SP from sensory neurones, as an effective topical agent for psoriatic itch; however, neither study examined this antipruritic effect in scalp psoriasis (20, 21). On the other hand, the current study may suggest that menthol, a commonly used over-the-counter antipruritic cooling agent, which activates both TRPV3 and TRPM8 channels, may exacerbate scalp psoriatic itch and should not be recommended for scalp psoriasis (22, 23).

The current results demonstrate that only the IL-23 and TNFα cytokines were increased in severely itchy psoriatic scalp lesions. These results differ somewhat from previous studies, which showed an increased gene expression of IL-17 and IL-31 in itchy psoriatic skin (8, 24, 25). The lack of any significant increase in CD68 + , a marker for macrophages and other monocytes, and CD3+ , a T cell marker, indicates that the increase in these cytokines is probably due to CD4+ T helper cells, consistent with previous literature (7).

Periostin, an extracellular protein highly associated with type 2 inflammation and an emerging “player” in itch sensation, was only found to be increased in no, mild, or moderate itch psoriatic scalp with a weak negative correlation to itch. This finding is consistent with previous data that states that psoriasis and psoriatic itch is due more to a type 1 and IL-17-driven immune response (7).

Extrapolation of the conclusions of the current study is restricted by the limited patient population and the examination of protein expression exclusively through immunofluorescent analysis. The patient population also had limited number of non-itchy and mildly itchy psoriatic patients, which could better differentiate mediators of psoriatic pathology from itch-specific pathology.

In conclusion, the current study provides some novel insights into the mechanism of psoriatic scalp itch, which are unique and partially differ from that of other body sites. These results may help indicate new therapeutic targets, such as TRPV3 or SP antagonists, while avoiding classical antipruritics, such as antihistamines and cooling agents that are ineffective for psoriatic itch.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was funded by an unrestricted grant by Leo Pharma to GY. EL is on advisory boards and/or a speaker for Janssen, Novartis, Medicamenta, and Sanfoi. LN is a consultant and/or investigator for Bells, Celldex, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi Regeneron. GY is a consultant and/or investigator for Celldex, Pfizer, Galderma, Leo, Sanofi Regeneron, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Kiniksa, Bellus, Trevi, and Escient

REFERENCES

- Prignano F, Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, et al. Itch in psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2009; 2: 9–13.

- Yosipovitch G, Goon A, Wee J, Chan YH, Goh CL. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of pruritus among patients with extensive psoriasis. Br J Deramtol 2000; 143: 969–973.

- Dickison P, Swain G, Peek JJ, Smith SD. Itching for answers: prevalence and severity of pruritus in psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol 2018; 59: 206–209.

- Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Wiśnicka B. Itching in patients suffering from psoriasis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2002; 10: 221–226.

- Stull C, Grossman S, Yosipovitch G. Current and emerging therapies for itch management in psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2016; 17: 617–624.

- Hawro M, Sahin E, Steć M, Różewicka-Czabańska M, Raducha E, Garanyan L, P et al. A comprehensive, tri-national, cross-sectional analysis of characteristics and impact of pruritus in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 2064–2075.

- Leon A, Rosen JD, Hashimoto T, Fostini AC, Paus R, Yosipovitch G. Itching for an answer: a review of potential mechanisms of scalp itch in psoriasis. Exp Dermatol 2019; 28: 1387–1404.

- Nattkemper LA, Tey HL, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Lee H, Mollanazar NK, Albornoz C, et al. The genetics of chronic itch: gene expression in the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with severe itch. J Invest Dermatol 2018; 138: 1311–1317.

- Yosipovitch G, Rosen JD, Hashimoto T. Itch: from mechanism to (novel) therapeutic approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 142: 1375–1390.

- Bin Saif GA, Ericson ME, Yosipovitch G. The itchy scalp – scratching for an explanation. Exp Dermatol 2011; 20: 959–968.

- Amatya B, El-Nour H, Holst M, Theodorsson E, Nordlind K. Expression of tachykinins and their receptors in plaque psoriasis with pruritus. Br J Dermatol 2011; 164: 1023–1029.

- Jiang WY, Raychaudhuri SP, Farber EM. Double-labeled immunofluorescence study of cutaneous nerves in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 1998; 37: 572–574.

- Kim TW, Shim WH, Kim JM, Mun JH, Song M, Kim HS, et al. Clinical characteristics of pruritus in patients with scalp psoriasis and their relation with intraepidermal nerve fiber density. Ann Dermatol 2014; 26: 727–732.

- Pariser DM, Bagel J, Lebwohl M, Yosipovitch G, Chien E, Spellman MC. Serlopitant for psoriatic pruritus: a phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: 1314–1320.

- Azimi E, Reddy VB, Pereira PJS, Talbot S, Woolf CJ, Lerner EA. Substance P activates Mas-related G protein-coupled receptors to induce itch. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140: 447–453.e3.

- Petersen LJ, Hansen U, Kristensen JK, Nielsen H, Skov PS, Nielsen HJ. Studies on mast cells and histamine release in psoriasis: the effect of ranitidine. Acta Derm Venereol 1998; 78: 190–193.

- Zhang Y, Shi Y, Lin J, Li X, Yang B, Zhou J. Immune cell infiltration analysis demonstrates excessive mast cell activation in psoriasis. Front Immunol 2021; 12: 773280.

- Sun, S, Dong, X. Trp channels and itch. Semin Immunopathol 2016; 38: 293–307.

- Wilson SR, Bautista DM. Role of transient receptor potential channels in acute and chronic itch. In: Carstens E, Akiyama T, editors. Itch: mechanisms and treatment. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2014, chapter 16.

- Bernstein JE, Parish LC, Rapaport M, Rosenbaum MM, Roenigk Jr HH. Effects of topically applied capsaicin on moderate and severe psoriasis vulgaris. J Am Acad Deramtol 1986; 15: 504–507.

- Ellis CN, Berberian B, Sulica VI, Dodd WA, Jarratt MT, Katz HI, et al. A double-blind evaluation of topical capsaicin in pruritic psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 29: 438–442.

- Xie Z, Hu H. TRP channels as drug targets to relieve itch. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2018; 11: 100.

- Patel T, Ishiuji Y, Yosipovitch G. Menthol: a refreshing look at this ancient compound. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57: 873–878.

- Ruano J, Suárez-Fariñas M, Shemer A, Oliva M, Guttman-Yassky E, Krueger JG. Molecular and cellular profiling of scalp psoriasis reveals differences and similarities compared to skin psoriasis. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0148450.

- Narbutt J, Olejniczak I, Sobolewska-Sztychny D, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, Stowik-Kwiatkowska I, Hawro T, et al. Narrow band ultraviolet B irradiations cause alteration in interleukin-31 serum level in psoriatic patients. Arch Dermatol Res 2013; 305: 191–195.