ORIGINAL REPORT

Truncal Acne in Adolescents and Young Adults: Self-reported Perception

Fabienne BALLANGER1, Jean Paul CLAUDEL2, Marie-Thérèse LECCIA3, Nicole AUFFRET4, Anna Stromstedt CAMERATI5, Pierre-Olivier DUFAUX5, Adrien MARQUIÉ6 and Brigitte DRÉNO7

1Private practice, Talence, 2Private practice, Tours, 3Department of Dermatology, Allergology and Photobiology, CHU A Michallon, Grenoble, 4Private practice, Paris, 5Parents and Educator School, Ile de France, Paris, 6Independent Consultant in Statistics, Paris and 7Nantes Université, INSERM, CNRS, Immunology and New Concepts in ImmunoTherapy, INCIT, UMR 1302/EMR6001, Nantes, France

No epidemiological information about truncal acne is available. This study assessed the self-reported impact of truncal acne in adolescents and young adults, using an internet survey in France in 1,001 adolescents and young adults with truncal acne. Participants’ mean age was 18.6 ± 4.3 years, 75.7% were females, 52.9% reported severe and 16.0% very severe truncal acne; 90.0% of participants with truncal acne also reported past or ongoing facial acne. Stress (46.3%), a diet high in lipids (33.2%), and sleeplessness (27.0%) were considered to be triggers of truncal acne; 44.7% consulted at least 1 healthcare professional and 28.1% searched the internet or social network for information about truncal acne. Of subjects with truncal acne, 68.4% thought constantly about their condition. Overall, 79.9% of the participants with severe acne vs 41.8% with mild or moderate acne: 41.8% thought about their acne all the time (p < 0.0001). Truncal acne heavily or very heavily impacted quality of life of 38.7% of participants. It impacted females significantly more than males (p < 0.0001). Significantly (p < 0.001) more females than males reported facial acne. A significant (p = 0.0067) association was observed between the severities of facial and truncal acne. The self-perceived impact of truncal acne in adolescents and young adults highlights the need for information as well as reinforced medical and psychological care.

Key words: acne; adolescents; internet survey; perception; quality of life; truncal acne; young adults.

SIGNIFICANCE

More than 1,000 subjects responded within 2 months to this national questionnaire, thereby confirming their interest in truncal acne. The results highlight that truncal acne is an underestimated health issue, which causes not only a physical, but also an important psychological, burden in a fragile part of the population. This survey provides information about the perception of truncal acne in adolescents and young adults with this condition, and highlights the need for providing information as well as reinforced medical and psychological care for those who are heavily impacted by truncal acne.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv5123. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.5123.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Feb 14, 2023; Published: Mar 28, 2023

Corr: Brigitte Dréno, Nantes Université, INSERM, CNRS, Immunology and New Concepts in ImmunoTherapy, INCIT, UMR 1302/EMR6001, FR-44000 Nantes, France. E-mail: brigitte.dreno@atlanmed.fr

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

INTRODUCTION

Acne vulgaris, or acne, is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with a multifactorial pathogenesis (1, 2). In the past, acne has been mainly described and investigated for its presence on the face, although it also frequently occurs on the trunk. Consequently, treatment for truncal acne consists mainly of products developed for facial acne.While truncal acne is increasingly frequently a reason for dermatology consultation, very little information is available (3–5). A review of the data available regarding truncal acne was published in 2020 (6) and a holistic tool to assess the severity of truncal acne was proposed in 2022 (7). Despite increasing interest, to date no epidemiological data regarding truncal acne have been published and no real-life information about its patient-perceived impact on daily life, quality of life (QoL) or stress (defined as any change that triggers physical, emotional or psychological concerns) is available in the literature (8).

The aims of this study were to assess the self-perceived impact of truncal acne on the daily life and QoL of participants in France and to collect epidemiological data concerning adolescents and young adults, in order to broaden our knowledge of truncal acne.

METHODS

Together with Fil Santé Jeunes (FSJ: Youth Health Helpline, https://www.filsantejeunes.com), an exploratory anonymous internet survey on truncal acne in adolescents of any ethnicity, aged at least 12 years and able to read and understand French, was conducted in France between September and October 2021. FSJ is a non-commercial and ethical institution that conducts internet surveys about health concerns of adolescents and young adults. A short questionnaire using lay language based on items regarding the subject’s daily life, daily routine and QoL was developed together with FSJ, based on the experience of FSJ in running internet surveys in this specific population. The survey was published on the FSJ website, and visitors with truncal acne were invited to participate. The detailed questionnaire is shown in Table SI. According to French legislation, the survey did not require independent ethics committee approval. However, all attempts were made to keep the identity of the participants anonymous, and to protect individual data from external access, according to the European regulations for individual data protection (European General Data Protection Regulation, 2018).

Statistical analysis

No minimum sample size was considered necessary for this mainly descriptive statistical analysis. Subgroup analyses included groups based on sex, age (< 18, 18–25 and > 25 years) and truncal acne severity, combining data from participants with mild, moderate, severe, and very severe truncal acne, as well as the impact on QoL, grouping participants who reported being not concerned, never or rarely impacted, and those being sometimes, often, very often or constantly impacted. Percentages were calculated excluding missing values. The χ2 test was used, and significance levels were set at 5%. SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Demographic and general data on truncal acne

Overall, 1,001 subjects completed the survey. Mean age was 18.6 ± 4.3 years; a large majority (75.7%) of respondents were female. When grouping truncal acne severity grades, 31.2% reported mild or moderate, and 68.8% severe or very severe truncal acne. Ninety percent (90.0%) of participants with truncal acne also reported past (24.3%) or ongoing facial acne (65.7%); 10.0% reported never having had facial acne. Detailed demographic general truncal and facial acne data are shown in Table I.

| Global population(n = 1001) | Males(n = 227) | Females(n = 706) | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 18.6 ± 4.3 | 19.4 ± 4.3 | 18.3 ± 4.3 |

| Min–max, years | 11–26 | 12–26 | 11–26 |

| < 18 years, n (%) | 540 (53.9) | 102 (44.9) | 401 (56.8) |

| 18–25 years, n (%) | 313 (31.3) | 84 (37.0) | 212 (30.0) |

| > 25 years, n (%) = 1,001 | 148 (18.8) | 41 (18.1) | 93 (13.2) |

| Truncal acne severity* (n = 933), n (%) | |||

| Mild | 19 (1.9) | 5 (2.2) | 14 (2.0) |

| Moderate | 293 (29.3) | 59 (26.0) | 204 (28.9) |

| Severe | 529 (52.9) | 115 (50.7) | 387 (54.8) |

| Very severe | 160 (16.0) | 48 (21.2)) | 101 (14.3) |

| Facial acne (n = 1,001), n (%) | |||

| Never had acne | 100 (10.0) | 24 (10.6) | 70 (9.9) |

| Had acne in the past | 243 (24.3) | 71 (31.3) | 146 (20.1) |

| Currently having acne | 658 (65.7) | 132 (58.2) | 490 (69.4) |

| Facial acne severity* (n = 839), n (%) | |||

| Mild | 109 (12.9) | 37 (18.2) | 72 (11.3) |

| Moderate | 389 (46.4) | 107 (52.7) | 282 (44.3) |

| Severe | 281 (33.5) | 48 (23.7) | 233 (36.6) |

| Very severe | 60 (7.2) | 11 (5.4) | 49 (7.7) |

| Family history of acne: yes (n = 988), n (%) | 776 (78.5) | 170 (76.6) | 556 (79.5) |

| Residential background (n = 1,001), n (%) | |||

| Urban/suburban area | 601 (60.0) | 136 (59.9) | 431 (61.1) |

| Countryside | 400 (40.0) | 91 (40.1) | 275 (39.0) |

| Activity (n = 1,001), n (%) | |||

| College | 247 (24.7) | 37 (16.3) | 197 (27.9) |

| High school | 327 (32.7) | 76 (33.5) | 225 (31.9) |

| University | 158 (15.8) | 44 (19.4) | 104 (14.7) |

| Employed | 219 (21.9) | 60 (26.4) | 141 (20.0) |

| Unemployed | 50 (5.0) | 10 (4.4) | 39 (5.5) |

| *According to the subject. | |||

Truncal acne triggers

Participants considered stress (46.3%), followed by a diet high in lipids (33.2%), and sleeplessness (27.0%) to be acne triggers; 44.2% did not know what could trigger their truncal acne.

Statistically significant differences were observed for whether subjects considered the following factors to be triggers of truncal acne: alcohol consumption (< 18 years: 5.2%, 18–25 years: 10.5%, and > 25 years: 13.5%; p = 0.0007) and smoking (< 18 years: 3.7%, 18–25 years: 9.3%, and > 25 years: 11.5%; p = 0.0002); significantly (p = 0.0316) more aged < 18 years (47.8%) than those aged 18–25 years: 41.2%) or aged > 25 years (37.2%) did not know what could trigger their truncal acne.

Significantly more females than males (26.5% vs 17.6%, p = 0.0068) considered that a diet high in lipids, cosmetic products (10.5% vs 2.6%, p = 0.0002), anxiolytics (3.7% vs 0.0%, p = 0.0034) and stress (52.0% vs 42.3%, p = 0.0111) were triggers of truncal acne. Conversely, significantly more males than females considered cannabis (4.0% vs 1.6%, p = 0.0294) or alcohol consumption (12.3% vs 7.5%, p = 0.0246) to be triggers of truncal acne.

More than half of all females (51.1%) believed that menstruation was the main trigger for their truncal acne and significantly more females aged > 18 years considered that an implant (4.9% vs 0.3%) or contraception pill (15.4% vs 4.7%) trigger their truncal acne, compared with females aged < 18 years (all p < 0.0001). Menstruation was significantly more frequently (59.6%) considered to trigger truncal acne by females with mild or moderate acne than by females with severe or very severe acne (47.3%); 50.8% of females with severe or very severe acne compared with 38.5% with mild to moderate acne did not know what could trigger their truncal acne (all p = 0.0025).

Significantly (p = 0.0099) more participants (46.9%) with severe or very severe truncal acne, compared with those with mild or moderate acne (38.1%), did not know what triggers their truncal acne.

Treatment information sources

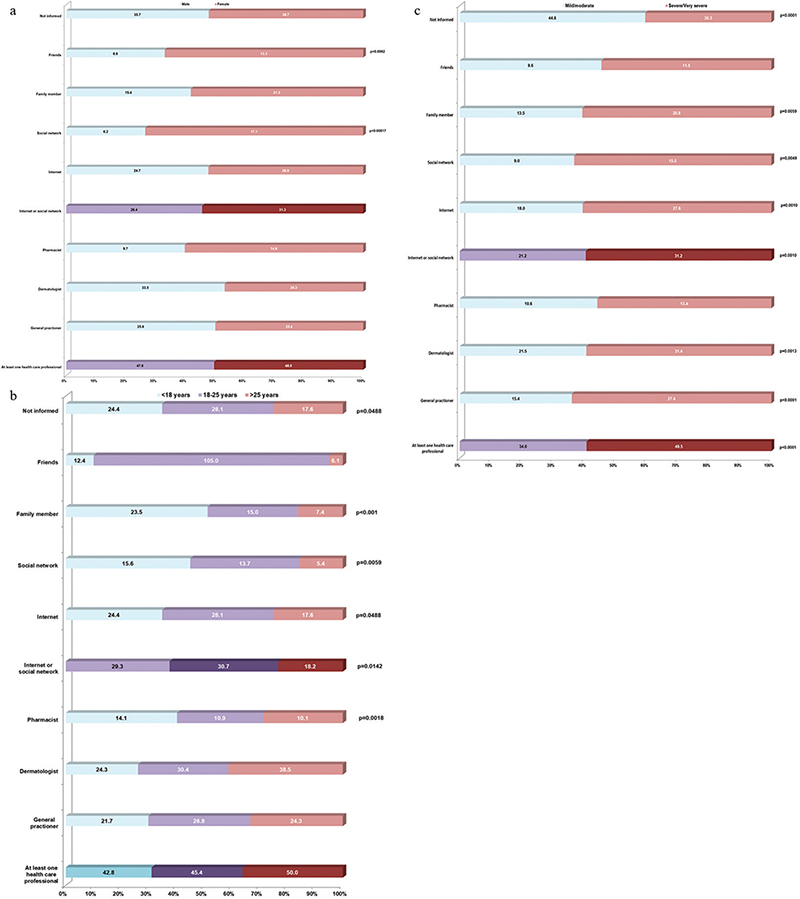

Globally, 44.7% of participants consulted at least 1 healthcare professional (HCP) to obtain information about truncal acne treatment; 28.3% consulted a dermatologist, 23.7% a general practitioner and 12.5% a pharmacist; the remaining participants consulted other HCPs. Information from the internet or social networks was gathered by 28.1% of responders. Information obtained from family members accounted for 18.5%, and 10.9% obtained information from friends. One-third (34.8%) of all participants did not consult any sources of information about truncal acne.

Significantly (p = 0.0018) more participants aged > 25 years (38.5%) consulted a dermatologist than those aged 18–25 years (30.4%) and those aged < 18 years (24.3%). Conversely, significantly (p = 0.0142) more participants aged < 18 years (29.3%) or aged 18–25 years (30.7%) consulted the internet or social networks, compared with participants aged > 25 years (18.2%), or asked family members (23.5% and 15.0% vs 7.4% for < 18 years, 18–25 years and > 25 years, respectively; p < 0.0001) for information.

More females than males were interested in obtaining information from social networks (17.1% vs 6.2% for females and males, respectively; p < 0.0001) or from friends (13.3% vs 6.6% for females and males, respectively; p < 0.0062).

The more severe their truncal acne, the more participants searched for information by consulting HCPs (49.5% vs 34.0% for severe or very severe acne vs mild or moderate acne respectively; p < 0.0001), social networks/the internet (31.2% vs 21.2% for severe or very severe acne vs mild or moderate acne, respectively; p = 0.0010) or family members (20.8% vs 13.5% for severe or very severe acne vs mild or moderate acne, respectively; p = 0.0059). The less severe their truncal acne, the less they searched for information (44.6% vs 30.3% for mild or moderate vs severe or very severe acne, respectively; p < 0.0001). Detailed results are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Information sources. (a) According to sex. (b) According to age group. (c) According to truncal acne severity group.

Financial support for treatment

Two-thirds (68.4%) of participants stated that their parents would pay for truncal acne treatment. The younger the participants, the higher they considered the willingness of their parents to pay (< 18 years: 72.5%, 18–25 years: 65.8%, > 25 years: 59.1%; p = 0.0073). This was also observed when stratifying according to severity groups: significantly (p < 0.0001) more parents were considered willing to pay for care (73.5%) when truncal acne was severe or very severe, compared with 56.8% when acne was mild or moderate.

Daily life and quality of life

Two-thirds (68.4%) of all participants were concerned about their truncal acne; among them 44.7% often, 33.4% all the time, and 21.9% sometimes. The more severe their truncal acne, the more frequently they were concerned (severe or very severe acne: 79.9% vs mild or moderate acne: 41.8%; p < 0.0001). Significantly more females than males were concerned about their truncal acne all the time (37.5% vs 19.6%; p = 0.0004).

According to the participants, truncal acne heavily or very heavily impacted QoL (38.7%), with no difference between age classes. QoL was significantly (p < 0.0001) more impacted in females (heavy or very heavy impact: 42.7%) than in males (26.1%).

The more severe the truncal acne, the heavier the impact on QoL, with 49.4% of participants with severe or very severe truncal acne reporting a heavy or very heavy impact, compared with 13.8% with mild or moderate truncal acne. Participants with mild or moderate truncal acne (50.2%) reported not being or only marginally being impacted, compared with 16.4% with severe or very severe truncal acne (p < 0.0001).

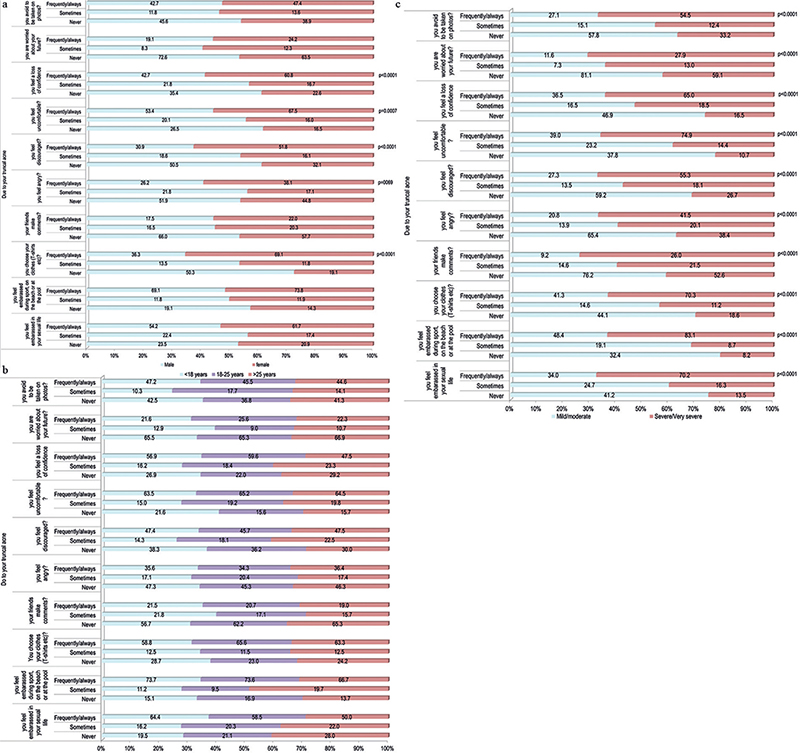

Fig. 2 details the results of the different QoL questions by sex, age class, and truncal acne severity groups, as well as according to frequencies.

Fig. 2. Impact of truncal acne on quality of life. (a) According to sex. Significantly more females reported a loss of confidence (p < 0.0001), feeling uncomfortable (p = 0.0007), discouraged (p < 0.0001) or angry (p < 0.0001). (b) According to age class. No statistically significant differences were observed between age groups. (c) According to truncal acne severity group. Severe or very severe acne significantly (all p < 0.0001) impacted on questioned quality of life items.

Significantly more females reported a loss of confidence, feeling uncomfortable, discouraged or angry, and selected their clothes accordingly (all p ≤ 0.0069).

When analysing according to truncal acne severity groups, a statistically significant (p < 0.0001) higher impact on all questions was reported by participants with severe or very severe truncal acne.

Facial acne

A majority of participants (90.0%) had facial acne at the time the survey was conducted or reported past facial acne, with significantly (p < 0.001) more females (69.4%) than males (58.2%) currently having facial acne. This ratio was inverted if patients reported past facial acne (males: 31.23 vs females: 20.7%). A total of 46.4% of participants reported moderate and 33.5% reported severe facial acne. Mild facial acne was reported by 13.0% and very severe facial acne by 7.2%. The prevalence of severe or very severe facial acne was significantly (p < 0.001) higher in females (44.3%) than in males (29.1%), in participants aged < 18 years (48.4%) and in those aged 18–25 years (33.9%) than in those aged > 25 years (22.4%, p = 0.008).

When stratifying according to age group, significantly (p < 0.003) more participants aged < 18 years (79.6%) than those aged 18–25 years (55.6%) or aged > 25 years (36.5%) reported ongoing facial acne. Conversely, significantly (p < 0.003) more participants aged > 25 years (43.9%) than those aged 18–25 years (1.0%) or < 18 years (15.0%) reported past facial acne. Significantly (p < 0.003) more participants aged 18–25 years (13.4%) or above (19.6%) declared having never had facial acne, compared with 5.4% aged < 18 years.

A statistically significant (p = 0.0067) association was observed between the severity of facial and truncal acne. The more severe the truncal acne, the more severe facial acne: 65.1% with mild or moderate facial acne reported severe or very severe truncal acne, compared with 73.9% with severe or very severe facial acne who also reported severe or very severe truncal acne.

DISCUSSION

For this French survey, 1,001 subjects provided data about their perception of their truncal acne. Age distribution between subjects aged < 18 years (55%) and those who were older (45%) was well balanced; almost 70% reported severe or very severe truncal acne, which may be considered high and, due to the study design, the potential risk of confusing truncal acne and acneiform lesions cannot be discarded. In total, 90% reported past or ongoing facial acne. Almost 80% reported a family history of acne. Moreover, in females, facial acne, especially in young females, was associated with more severe truncal acne.

Participants considered that stress, a diet high in lipids, and sleep deprivation trigger truncal acne. When stratifying according to sex, a diet high in lipids, cosmetics, anxiolytics and stress were significantly (all p < 0.05) more frequently reported by females, while cannabis or alcohol consumption were significantly (all p < 0.05) more frequently identified by males. Almost half of all responders with severe or very severe truncal acne, compared with those with mild-to-moderate acne, did not identify any trigger for truncal acne. This may be because easily available information about truncal acne is still lacking. Thus, providing more and easily accessible information may increase patients’ awareness.

When focusing on females, those aged > 18 years considered that menstruation and contraception pills trigger acne. Implants or hormonal contraception pills were significantly (p < 0.0001) more frequently reported to cause truncal acne in participants aged > 18 years. This latter result may be explained by the fact that contraception may be used more regularly by females aged 18 years or above, and may therefore be related to their truncal acne.

Interestingly, the level of information known about the condition was related to the severity of truncal acne: participants with severe truncal acne were significantly (p < 0.0001) better informed about the condition than those with less severe truncal acne.

Globally, 44.7% of the respondents asked a HCP, including a dermatologist, GP or a pharmacist, for information about treatment for their truncal acne, while social networks and the internet accounted for 28.1% of all information sources. According to the age groups, significantly (p = 0.0018) more participants aged 18 years and over asked for professional information than those aged under 18 years. This latter group searched the internet or social networks significantly more frequently for information (p < 0.0001), with the percentage of females being almost 3 times higher than that of males. It is very important that this information is taken into consideration by the HCP. The younger the participants, the more they were likely to obtain information from the internet and social networks.

The results of the current study reflect real-life, where, unsurprisingly, female adolescents are likely to obtain beauty and health-related information from “influencers”, who, most of the time, are not medically qualified to provide healthcare-related advice (9). However, more than one-third of respondents had never previously searched for information about truncal acne care. These findings parallel those described above, maintaining that more information should be provided to this population.

Even though younger subjects search for information more frequently on the internet and social networks, these results also show that HCP remain the main source of information. Therefore, adequate communication and the suitable training of these caregivers remain mandatory to provide patients with clear, recent, and concise information about the most suitable treatment for truncal acne, and thus to improve the patients’ adherence to treatment. Patient education may be provided by explaining the treatment leaflets or by using specifically prepared videos explaining the issue of truncal acne and discussing with the patient how to manage it properly (10).

While the internet and social networks allow easy access to information, it is key to provide clinically and scientifically verified knowledge that is easily accessible and understandable, in order to help patients learn about their condition and treatment options.

Overall, almost 75% of participants (p = 0.0073) aged < 18 years responded that their parents would pay for care; this percentage decreased with age, possibly due to financial independence. Similar results were obtained according to severity, and significantly (p < 0.0001) more participants with severe or very severe acne responded that their parents would pay for their treatment. Again, these figures confirm that patients would be willing to take care of their truncal acne. By improving information and education, patients would certainly request suitable pharmacological care and seek the help of an HCP.

The results of the current survey demonstrate that truncal acne has an undeniable impact on mental health and quality of life of adolescents and young adults. Two-thirds thought constantly about their truncal acne. This concern was important not only for those with severe or very severe acne (p < 0.0001), but also for participants with milder forms of truncal acne, with a significant predominance of females (p = 0.0004) compared with males.

More than two-thirds of the participants reported that their daily life and QoL was heavily impacted by their truncal acne. Significantly more females reported a loss of confidence, feeling uncomfortable, discouraged, or angry, and selected their clothes accordingly (all p < 0.0069).

Study limitations

This survey has several possible biases and limitations. First, sex was unequally distributed with 75.7% of female participants. Moreover, the survey did not ask for the truncal acne to be confirmed by a dermatologist prior to completion; thus, differential diagnoses (i.e. folliculitis) may not be discarded and severity of acne is subjective. The study did not plan for a sample size, as, currently, there is no reference study that would have enabled a minimum sample size to be calculated.

The aim of the current study was not to collect data from subjects who were selected by dermatologists or were potentially influenced by a diagnosis, but to obtain information about the self-perceived impact of truncal acne on daily life and QoL from the perspective of those who were directly concerned by the condition, and thus, to obtain an inside view from this specific population, which was not influenced by an HCP. This survey did not require a minimum number of participants, which may raise issues concerning the power of the study. Moreover, the study did not ask for ethnicity to be confirmed.

Despite these issues, the present results undoubtedly highlight the fact that truncal acne impacts the daily life and QoL of adolescents and young adults, especially among females.

Regarding its impact on QoL, the authors decided, in agreement with FSJ, not to use a clinically validated QoL questionnaire, which may be useful in clinical research, but which is limited in real-life conditions in the younger population, especially due to its length and when used via the internet. Therefore, it was agreed, together with FSJ, to develop a short questionnaire with questions that the authors considered to be the most pertinent, and which was validated by FSJ who then adapted it for the target population.

Conclusion

Truncal acne remains an underestimated health issue that causes both a physical and an important psychological burden. This survey provides information about the perception of truncal acne in adolescents and young adults for the first time, and highlights the need for information to be provided and for reinforced medical and psychological care of this population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the participation of the respondents, and the writing assistance of Karl Patrick Göritz, SMWS, Scientific and Medical Writing Services, France.

This expert group was funded by Galderma International, France.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors received honoraria from Galderma International to participate in this board.

REFERENCES

- Platsidaki E, Dessinioti C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Res 2018; 7: F1000.

- Dreno B. What is new in the pathophysiology of acne, an overview. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31:8–12.

- Del Rosso JQ. Management of truncal acne vulgaris: current perspectives on treatment. Cutis 2006; 77: 285–289.

- Tan JK, Tang J, Fung K, Gupta AK, Thomas DR, Sapra S, et al. Prevalence and severity of facial and truncal acne in a referral cohort. J Drugs Dermatol 2008; 7: 551–556.

- Tan J, Thiboutot D, Popp G, Gooderham M, Lynde C, Del Rosso J, et al. Randomized phase 3 evaluation of trifarotene 50 mug/g cream treatment of moderate facial and truncal acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 1691–1699.

- Poli F, Auffret N, Leccia MT, Claudel JP, Dréno B. Truncal acne, what do we know? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 2241–2246.

- Auffret N, Nguyen JM, Leccia MT, Claudel JP, Dréno B. TRASS: a global approach to assess the severity of truncal acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 897–904.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Stress 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress#:~:text = Stress%20can%20be%20defined%20as,to%20your%20overall%20well%2Dbeing

- Ward S, Rojek N. Acne information on instagram: quality of content and the role of dermatologists on social media. J Drugs Dermatol 2022; 21: 333–335.

- Dréno B, Gallo RL, Berardesca E, Griffiths CEM. Advocacy for a shared physician/patient approach for the management of acne, rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis and photodamage. Eur J Dermatol 2022; 32: 138–139.