ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Impact of Atopic Dermatitis on Patients and their Partners

Laurent MISERY1,2, Julien SENESCHAL3, Florence CORGIBET4, Bruno HALIOUA5, Adrien MARQUIÉ6, Stéphanie MERHAND7, Gaelle LEFUR8, Delphine STAUMONT-SALLE9, Christina BERGQVIST10, Charles TAIEB11, Khaled EZZEDINE10,12 and Marie-Aleth RICHARD13

1Department of Dermatology, Brest University Hospital, Brest, 2French Society of Human Skin Sciences, [SFSHP], Maison de la dermatologie, Paris, 3Department of Dermatology and Pediatric Dermatology, National Reference Center for Rare Skin disorders, Hospital Saint-André, Bordeaux, 4Dermatologist, private practice, Dijon, 5Dermatologist, private practice, Paris, 6Data analyst, Paris, 7Association Francaise de l’Eczema, 8Sociologist, Paris, 9Department of Dermatology, Lille University Hospital, Lille, 10Department of Dermatology, Hôpital Henri Mondor, APHP, Creteil, 11Emma, Patients priority, 12EA 7379 EpidermE, Université Paris-Est Créteil (UPEC), Créteil, and 13Department of Dermatology, Aix-Marseille University, La Timone University Hospital, Marseille, France, CEReSS-EA 3279, Health Services and Quality of Life Research Centre, Aix Marseille University, Dermatology Department, La Timone University Hospital APHM, 13385, Marseille, France

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, relapsing and inflammatory skin disease. The impact of atopic dermatitis on the partners living with patients has been poorly investigated. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of atopic dermatitis in the daily lives of adult patients and to assess the burden of the disease on their partners. A population-based study was conducted on a representative sample of the general population of French adults aged 18 years of age using stratified, proportional sampling with a replacement design. Data were collected on 1,266 atopic dermatitis patient-partner dyads (mean age of patients 41.6 years, 723 (57.1%) women). The mean age of partners was 41.8 years. Patient burden, measured by the Atopic Dermatitis Burden Scale for Adults (ABS-A) score, was closely related to the objective atopic dermatitis severity: the mean score in the mild group (29.5) was significantly lower than in the moderate (43.9) and severe groups (48.6) (p < 0.0001). Partner burden, measured by the EczemaPartner score, was highly related to atopic dermatitis severity (p < 0.0001). Daytime sleepiness, measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, showed a mean score of 9.24 in patients and 9.01 in their partners, indicating impaired sleep. Atopic dermatitis was found to decrease sexual desire in 39% and 26% of partners and patients respectively.

Key words: atopic dermatitis; partners; burden; quality-of-life; sleep.

SIGNIFICANCE

Atopic dermatitis can impart a profound burden on patients and their partners including sleep disturbance and sexual health impairment. This is not surprising, considering that partners share a significant part of the challenges faced by the affected individuals. These results merit particular attention for future patient-centred care provision. Indeed, the burden of atopic dermatitis on partners should be taken into consideration by physicians when implementing education programmes dedicated to patients and their loved ones. Targeting partners with education and psychosocial support can eventually decrease the burden.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv5285. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.5285.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Apr 4, 2023; Published: Jun 26, 2023

Corr: Charles Taieb, Patient Priority Department, European Market Maintenance Assessment, FR-94120 Fontenay sous Bois, France. E-mail: charles.taieb@emma.clinic

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing and inflammatory skin disease. In France, the prevalence of AD in the general population over 15 years of age is estimated at 4.6% (1) and prevalence of adult AD is estimated at around 2–10% (2, 3). Although AD is not a life-threatening disease, it has profound impact on quality of life (QoL) (4, 5). Pruritus, the main symptom of AD, often leads to frequent scratching, skin pain, and skin infections. AD has been shown to significantly impair sleep quality (6). Moreover, whether the patient is a child, teenager or adult, AD may have a secondary negative impact on the physical, emotional, social, and economic elements of the patient’s family life (7, 8). The term “greater patient” was coined by Basra & Finlay (9) to describe the immediate close social group affected by a person having skin disease. Since AD is probably a lifelong illness, its negative impact on the lives of patients and their families occurs throughout the lifespan. Previous studies on AD have focused mainly on children (10). However, adult patients with AD may also share the psychosocial burden of their disease with family members and partners (5, 11). Different burdens of AD arise as patients enter adulthood, including adverse effects on sexual health and affective relationships (12–14). Partners of patients with chronic diseases face multiple challenges, and may have to adjust their activities of daily living.

Although studies have focused on the health-related QoL and burden of AD in patients themselves, data regarding the impact AD has on the partners living with them are scant (15). A few studies have focused on the impact of AD on an individual’s sexuality, but information regarding the difficulties experienced by the partners is very limited (16, 17).

The aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the impact of AD in the daily lives of adult patients in the French population and to assess the burden of the disease on their partners.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was an observational, cross-sectional study. The study was approved by a local ethics committee at CHU de Grenoble, France (reference number 20.04.18.61210) and was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

Survey participants were recruited between January and April 2021, from a representative sample of French adults recruited by a polling institute (HC Conseil Paris, France) from the general adult population above 18 years of age using stratified, proportional sampling with a replacement design. Respondents who reported being diagnosed with AD by a physician were invited to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria were: ability to understand French; provision of consent to participate in the study after receipt of written information about the study; age above 18 years. Participants also gave consent for their partner’s participation in the study. The patient and spouse were asked to respond separately, with the spouse having to respond within a maximum of 2 or 3 days.

Study procedures

Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding sociodemographic and personal information, including age, sex, and relationship duration. Partners were asked to complete a different questionnaire regarding sociodemographic and personal information, including age but not sex.

Patients were asked to self-evaluate the global clinical severity of their AD (into mild, moderate, or severe). Partners were also asked to evaluate the global clinical severity of their partner’s AD (as mild, moderate, or severe). Objective clinical severity of AD was assessed by the patient using the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) (18). POEM is a self-assessment tool used to monitor disease activity in children and adults with AD. The questionnaire asks about the frequency of occurrence of 7 symptoms during the preceding week (itching, sleep, bleeding, weeping, skin cracking, skin flaking off, and skin dryness). It is rated out of 28. The previously proposed banding for POEM scores were used to create 3 groups: mild (0–7), moderate (8–16), and severe (17–28) (19).

Patients and partners were asked to complete several questionnaires on QoL and burden, as well as a non-validated questionnaire about sexuality, which was used in a previous study (13).

The burden of AD was assessed by the patient using the Atopic Dermatitis Burden Scale for Adults (ABS-A) (20). The ABS-A questionnaire is a validated tool that assesses the burden of AD in adult patients. The questionnaire consists of 18 items grouped into 4 domains (“daily life”, “economic constraints”, “care and management of disease”, and “work and stress”). It is rated out of 90. A higher ABS-A score reflects a higher AD burden.

The burden of AD was assessed by the partner using EczemaPartner (21). It is a validated questionnaire that evaluates the burden of partners of patients with AD.

It is structured around 5 factors (Perceived strain by social reactions, Strain caused by cleaning, Acute emotional strain, Restrictions of social life, General emotional strain) cover the following areas: social, emotional, leisure domain. It is comprised of 15 items and is rated out of 60. A higher EczemaPartner score reflects a higher AD burden on the partner.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale, is a questionnaire that evaluates daytime sleepiness, and thus indirectly measures sleep disorders (22). It is comprised of 8 items and is rated out of 24. The higher the score, the higher the likelihood for a subject to fall asleep. If the Epworth score is ≤ 6, sleep is considered sufficient. A score ≥ 10 implies the presence of a sleep disturbance.

All the questionnaires were anonymous. The patients and their partners’ questionnaires were linked by a code to form a dyad.

Statistical methods

Categorical values are described as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables as means, ranges and standard deviations (SD), or median and quartiles. Categorical variables were analysed using the χ2 test. The mean scores of the different instruments were compared for different levels on different variables using the Jonckheere-Terpstra test. Statistical analyses were preformed using the SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 2,530 patients with atopic dermatitis confirmed by a physician were identified and recruited. Of these, 1,722 declared that they were living as a couple. A total of 1,266 spouses completed the questionnaire, i.e. a joint response rate of 73.5%. Data were collected on 1,266 AD patient-partner dyads. Their characteristics are detailed in Table I. The mean age of the patients was 41.6 years (range 18–83 years), and 723 (57.1%) patients were women. The mean age of partners was 41.8 years (range 16–79 years). The median duration of the relationship was 12 years (range 6–20 years).

Severity

According to the POEM scores of the respondents, 560 (44.23%) presented mild AD, 561 (44.31%) moderate AD, and 145 (11.45%) severe AD (Table I). Patients’ self–reported severity matched the severity established by the POEM score in 55% of cases; 25% overestimated their severity and 18% underestimated it. Partners’ reported severity matched the severity established by the POEM score in 52% of cases, and the patients’ self-reported severity in 70% of cases (Table II).

Burden

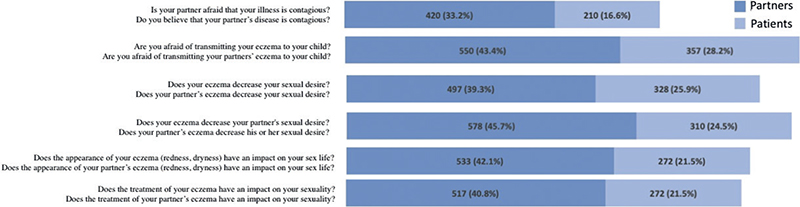

Patient burden, as measured by the ABS-A, was closely related to the objective AD severity: The mean (SD) score in the mild group was 29.5 (15.03) vs 43.9 (17.06) and 48.6 (18.52) in the moderate and severe groups, respectively (p < 0.0001) (Table III). A third of partners (420/1,266) believed that AD was contagious (Fig. 1). Patient burden was higher when the partner believed AD was contagious [50.78 (17.42) vs 31.76 (14.85); p < 0.0001].

Fig. 1. Impact of atopic dermatitis on atopic dermatitis on sex life according to the patients and the partners.

Partner burden, as measured by the EczemaPartner, was highly related to AD severity. The mean (SD) score in the mild group was 20.00 (14.38) vs 31.06 (14.72) and 32.98 (14.48) in the moderate and severe groups, respectively (p < 0.0001) (Table III). The scores for each item on the Eczema Partners are described in Table SI.

Similarly, partner burden was higher when he or she believed AD was contagious [50.80 (SD17.40) vs 20.40 (SD13.70); p < 0.0001].

The mean length of the couple relationship is 15.5 (± 11.9). For both the patient and the spouse the burden is greater the more recent the relationship p < 0.001 (Table SII).

Sleep

Daytime sleepiness, as measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), showed a mean score of 9.24 (SD 5.01) in patients and 9.01 (SD 4.83) in their partners, indicating impaired sleep. Analysis by severity of atopic dermatitis demonstrated significantly more daytime sleepiness with increasing AD severity in both groups (Table III). Patients slept on a mean of 6.68 (SD 1.52) h a night, and their partners slept 6.84 (SD 1.45) h. Hours of sleep decreased significantly as AD increased in severity, in both patients and their partners (Table IV). Among the 1,266 patient-partners dyads, 420 (33.2%) had both members with an ESS score > 9. This proportion was raised to 49.7% when AD was severe (Table IV).

Impact of AD on couple’s sex life

Fig. 1 depicts the answers of AD patients and their partners regarding the impact of atopic dermatitis on their sex life. AD had a negative impact on patients and their partners, which was more pronounced in partners. AD decreased sexual desire in 39% and 26% of partners and patients, respectively. Nearly half (46%) of partners believed that AD decreased his or her partner’s sexual desire, and a quarter of patients (25%) believed that their eczema decreased their partner’s sexual desire. A negative impact of AD on sex life was associated with higher ABS-A and EczemaPartner burden scores in patients and their partners respectively (Table V).

DISCUSSION

This real-world study on 1,266 AD patient-partner dyads in France is one of the very rare studies to have evaluated the impact of AD on partners beyond sexual health (17). The results suggest that AD has a detrimental effect on the QoL of affected individuals and their partners, including sleep disturbance and sexual health impairment. Whether in patients or in their partners, the burden increases with increasing severity of AD, regardless of how severity is measured. It is noteworthy that variations in QoL scores in partners mirror those of patients. Three real-world studies (2 in the USA and 1 in France, Germany the UK and the USA) have also demonstrated that a more severe AD, whether self-reported or assessed by POEM, has a higher impact on the QoL of patients (4, 23, 24). In 1 report, severe AD was 8 times more likely to cause a moderate-to-severe effect on DLQI compared with mild AD (24).

More than half of patients in this study had moderate-to-severe disease according to the self-administered objective POEM instrument. When patients and their partners were asked to globally evaluate AD severity (using the mild-moderate-severe scale), their assessment matched the severity established by the POEM in a little more than half of patients (55%) and partners (52%). Nevertheless, the perception of AD severity by partners was aligned with that of patients in 70% of cases. This excellent agreement between patients’ and partners’ global assessment, but relatively low agreement between the latter and the POEM scale, has also been described in a recent study in children with AD and their parents (25). Authors suggested a reasonable explanation for this inconsistency: the severity measured by POEM is related to symptoms occurring during the preceding week, whereas in patients and their relatives the assessment probably corresponds to a much longer timespan.

Patients and their partners had excessive daytime sleepiness, which worsened with AD severity. Hours of sleep also decreased significantly as AD increased in severity. Sleep disturbances are very common and burdensome in AD. They have been extensively explored in children with AD, and to a lesser extent in adults (6, 26–28). Increased disease severity is associated with reduced sleep quality, increased sleep-onset latency and reduced sleep efficiency (26). Sleep disturbances in AD is associated with increased psychological burden. In children with AD, sleep disorders have been shown to significantly reduce their QoL and that of their caregivers and other family members (26, 26). While patients and their partners were not asked whether they were living under the same roof, or sharing the same bed, bed sharing is a common practice. There is growing evidence suggesting that a sleep disorder in 1 partner may increase risk for a sleep disorder in the other partner, all the more so when 1 partner is affected by a condition associated with a sleep disorder (26, 29–31).

This study confirms and expands on the results of a previous study that found a decrease in sexual desire due to AD in both patients (39%) and their partners (26%) (13). Skin appearance of AD patients, location of lesions on visible or genital area, the presence of itch or pain are all factors that can have a negative impact on sexual life (9, 14). Sexual dysfunction in a relationship can in turn impart profound strain on a couple. One study determined that AD is associated with higher rates of separation and divorce, and AD patients are less likely to be living with a partner (32).

Strength and limitation

The large-scale and population-based approach, which allows for generalization of results to the French population contribute to the strength of our study. The study includes several limitations. Clinical severity of AD was measured using the POEM, a patient-reported outcome measure, and was not assessed by dermatologists. This study also lacked a control group; a comparison would have been helpful in discriminating whether these results are specific to AD, or are characteristic of any couple with another (or no) dermatological condition. Moreover, this study did not evaluate all the patients and partner-related parameters, such as level of education and marital status. Lastly, questions about how AD impacted the relationship on a daily basis, including sexual dysfunction, were not specifically asked.

Conclusion

AD can impart a profound burden on patients and their partners. This is not surprising, considering that partners share a significant part of the challenges faced by the affected individuals. These results merit particular attention for future patient-centred care provision. Indeed, the burden of AD on partners should be taken into consideration by physicians when implementing education programs dedicated to patients and their loved ones. Targeting partners with education and psychosocial support can eventually decrease the burden.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the participation of the subjects in this study. The authors also thank Nadir Mammar, Audrey Bourne-Chastel and Alexandre Lejeune for their support in the implementation of this project.

This study was funded by Pfizer.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Richard MA, Corgibet F, Beylot-Barry M, Barbaud A, Bodemer C, Chaussade V, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted prevalence estimates of five chronic inflammatory skin diseases in France: results of the “OBJECTIFS PEAU” study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 1967–1971.

- Rönmark EP, Ekerljung L, Lötvall J, Wennergren G, Rönmark E, Torén K, et al. Eczema among adults: prevalence, risk factors and relation to airway diseases. Results from a large-scale population survey in Sweden. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 1301–1308.

- Vinding GR, Zarchi K, Ibler KS, Miller IM, Ellervik C, Jemec GBE. Is adult atopic eczema more common than we think? A population-based study in Danish adults. Acta Derm Venereol 2014; 94: 480–482.

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Grayson MH, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 121: 340–347.

- Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the United States: an analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77: 274–279.e3.

- Ramirez FD, Chen S, Langan SM, Prather AA, McCulloch CE, Kidd SA, et al. Association of atopic dermatitis with sleep quality in children. JAMA Pediatr 2019; 173: e190025.

- Golics CJ, Basra MKA, Finlay AY, Salek S. The impact of disease on family members: a critical aspect of medical care. J R Soc Med 2013; 106: 399–407.

- Barbarot S, Silverberg JI, Gadkari A, Simpson EL, Weidinger S, Mina-Osorio P, et al. The family impact of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: results from an international cross-sectional study. J Pediatr 2022; 246: 220–226.e5.

- Basra MKA, Finlay AY. The family impact of skin diseases: the greater patient concept. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 929–937.

- Ali F, Vyas J, Finlay AY. Counting the burden: atopic dermatitis and health-related quality of life. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00161.

- Arima K, Gupta S, Gadkari A, Hiragun T, Kono T, Katayama I, et al. Burden of atopic dermatitis in Japanese adults: analysis of data from the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey. J Dermatol 2018; 45: 390–396.

- Halioua B, Maccari F, Fougerousse AC, Parier J, Reguiai Z, Taieb C, et al. Impact of patient psoriasis on partner quality of life, sexuality and empathy feelings: a study in 183 couples. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 2044–2050.

- Misery L, Finlay AY, Martin N, Boussetta S, Nguyen C, Myon E, et al. Atopic dermatitis: impact on the quality of life of patients and their partners. Dermatol Basel Switz 2007; 215: 123–129.

- Misery L, Seneschal J, Reguiai Z, Merhand S, Héas S, Huet F, et al. The impact of atopic dermatitis on sexual health. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 428–432.

- Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, Sevetson E, Block JK, Qureshi AA. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 26–30.

- Linares-Gonzalez L, Lozano-Lozano I, Gutierrez-Rojas L, Lozano-Lozano M, Rodenas-Herranz T, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Sexual dysfunction and atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Life Basel Switz 2021; 11: 1314.

- Ludwig CM, Fernandez JM, Hsiao JL, Shi VY. The interplay of atopic dermatitis and sexual health. Dermatitis 2020; 31: 303–308.

- Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient-oriented eczema measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 1513–1519.

- Charman CR, Venn AJ, Ravenscroft JC, Williams HC. Translating Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores into clinical practice by suggesting severity strata derived using anchor-based methods. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 1326–1332.

- Taïeb A, Boralevi F, Seneschal J, Merhand S, Georgescu V, Taieb C, et al. Atopic Dermatitis Burden Scale for Adults: development and validation of a new assessment tool. Acta Derm Venereol 2015; 95: 700–705.

- Shourick J, Taieb C, Seneschal J, Merhand S, Ezzedine K, Halioua B, et al. EczemaPartner – adapting a questionnaire to assess the impact of atopic dermatitis on partners of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: e192–193.

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991; 14: 540–545.

- Andersen L, Nyeland ME, Nyberg F. Higher self-reported severity of atopic dermatitis in adults is associated with poorer self-reported health-related quality of life in France, Germany, the U.K. and the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182: 1176–1183.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, Boyle J, Fonacier L, Gelfand JM, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139: 583–590.

- Mahe E, Shourick J, Mallet S, Abasq C, Bursztejn AC, Sampogna F, et al. Perceived clinical severity of atopic dermatitis in children: comparison between patients’ and parents’ evaluation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: e592–594

- Bawany F, Northcott CA, Beck LA, Pigeon WR. Sleep disturbances and atopic dermatitis: relationships, methods for assessment, and therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 1488–1500.

- Chang YS, Chou YT, Lee JH, Lee PL, Dai YS, Sun C, et al. Atopic dermatitis, melatonin, and sleep disturbance. Pediatrics 2014; 134: e397–405.

- Silverberg JI, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Margolis D, Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Grayson M, et al. Sleep disturbances in atopic dermatitis in US adults. Dermatitis 2022; 33: S104–113

- Parish JM, Lyng PJ. Quality of life in bed partners of patients with obstructive sleep apnea or hypopnea after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Chest 2003; 124: 942–947.

- Marklund H, Spångberg A, Edéll-Gustafsson U. Sleep and partner-specific quality of life in partners of men with lower urinary tract symptoms compared with partners of men from the general population. Scand J Urol 2015; 49: 321–328.

- Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Roberts RE. Impact of Spouses’ sleep problems on partners. Sleep 2004; 27: 527–531.

- Hua T, Silverberg JI. Atopic dermatitis in US adults: epidemiology, association with marital status, and atopy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 121: 622–624.