SHORT COMMUNICATION

Upadacitinib for Successful Treatment of Alopecia Universalis in a Child: A Case Report and Literature Review

Dianhe YU and Yunqing REN*

Department of Dermatology, The Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, National Clinical Research Center for Child Health, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, 310052, China. E-mail: yqren@zju.edu.cn

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: 5578. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.5578.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Feb 27, 2023; Published: Apr 4, 2023

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune inflammatory non-scarring disease characterized by well-defined patchy bald lesions, which has an approximate global prevalence of 2% (1). The aetiology of AA remains unclear, but several factors have been implicated in the development of the disease, including genetic, immunological and environmental factors. The association of AA and atopic dermatitis (AD) has been reported, and atopy is thought to increase the risk of AA (2). Treatment of alopecia universalis, the most severe type of AA, is challenging in children, since the therapeutic options are limited (3). Currently, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are emerging as potential therapies for AA; however, their therapeutic effects in children are not well defined. We report here a paediatric case of alopecia universalis concurrent with AD in which clinical remission was achieved with treatment with upadacitinib. In addition, a literature review of similar cases is presented.

CASE REPORT

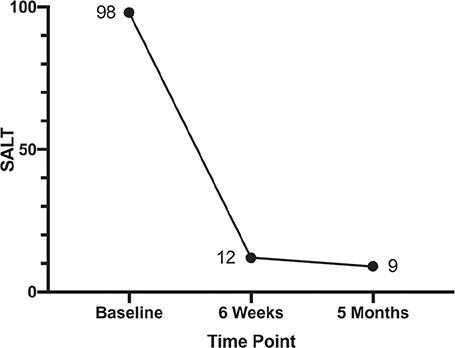

A 9-year-old female child (weighing 33 kg) presented with a 7-year history of alopecia universalis. She did not report any pain or pruritus of the scalp. Treatment with topical potent steroids, minoxidil, tacrolimus and oral compound glycyrrhizin tablets, and glucocorticoids was ineffective. The patient also had mild AD and her father had previously been diagnosed with allergic rhinitis. Physical examination revealed hair loss of the entire scalp, with the presence of only localized nummular tiny hairs (Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, 98) (Fig. 1A–C, Fig. 2). The patient had sparse eyebrows and eyelashes. Erythema, papules, and pigmentation affected the trunk, limbs, cubital fossa, and popliteal fossa (Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) score, 2.5). Laboratory tests showed elevated levels of eosinophils (1.36*109/L, 14.5%), aspartate aminotransferase (54 U/L), immunoglobulin E (146 IU/mL), thyroid peroxidase antibody (43.37 IU/mL) and thyroglobulin antibody (276.86 IU/mL). No abnormalities were observed in thyroid hormones, trace elements (including lead, zinc, copper, iron, magnesium, and calcium), 25-hydroxy vitamin D, anti-nuclear antibody, and T-SPOT TB test. Considering the lesser side-effects and the patients’ unwillingness to have injection therapy, oral upadacitinib was administered off-label at a dosage of 15 mg per day after obtaining informed consent from her parents. Sporadic hairs were observed after 2 weeks’ therapy. Six weeks later, regrowth of hair all over the scalp was noticed and her eyebrows and eyelashes had become dense (SALT score, 12) (Fig. 1D–F, Fig. 2). After 3 months’ treatment, the patient stopped upadacitinib due to significant regrowth of hair. At the 5-month follow-up visit, she had thick longer hair (SALT score, 9) (Fig. 1G–I, Fig. 2). In addition, the AD was in complete remission and no adverse events were detected.

Fig. 1. (A–C) Hair loss over the entire scalp and sparse eyebrows and eyelashes (Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT), 98) before treatment with upadacitinib. Only localized coin-sized patches of hair were seen. (D–F) Diffuse regrowth hair and thicker eyebrows and eyelashes (SALT score, 12) after 6 weeks’ treatment with upadacitinib. Longer thick hair (G–I) (SALT score, 9) after 3 months’ oral upadacitinib and 2 months’ discontinuation.

Fig. 2. Change in the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores during follow-up visits.

DISCUSSION

Traditional treatment choices for childhood AA include topical and systemic minoxidil, glucocorticoids, and immunosuppressants (3). Due to their significant side-effects, their application is limited. A deeper understanding of AA has resulted in the progress of targeted therapies, including JAK inhibitors, which target the shared downstream molecules of cytokines (i.e. interferon-γ and interleukin-15) that are pivotal in the pathogenesis of AA and AD. These have become the drugs with most potential to result in curative effects in both AA and AD (4). Clinical trials have confirmed the efficacy of first-generation JAK inhibitors in adult AA (5, 6), but for childhood AA their application is restricted to case series (7). Upadacitinib, a second-generation JAK inhibitor, is characterized by high selectivity with JAK1 and has been approved by the European Medicine Agency and the United States Food and Drug Administration, as an oral treatment for moderate to severe AD in adults and adolescents 12 years and older. Due to the critical role of interferon-γ and interleukin-15, which signal mainly through JAK1 in AA development and maintenance, upadacitinib was suggested as the treatment. To date, there is no literature reporting upadacitinib applied to AA or AD patients under 12 years of age, yet there is an ongoing clinical trial investigating the pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of upadacitinib in paediatric participants (aged between 2 and 12 years) with severe AD (NCT03646604). There are only 5 reports of AA cases treated with upadacitinib (8–11), in 4 of which the AA cases are concurrent with AD (8–10) and all of the 5 patients are adults. These patients were refractory to traditional treatments, such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and glucocorticoids. Dupilumab was prescribed to 3 of the patients, and AD lesions of 2 patients showed a temporary improvement but later relapsed, while the AA did not improve (9, 10). This treatment failed in AA and AD of another patient (10). When switched to upadacitinib, both AA and AD were under effective control. Except for 1 patient who did not specify the dosage (8), the other patients resumed 30 mg daily of upadacitinib. At the follow-up visit (up to 4 months), the treatment was well tolerated in all subjects, with no side-effects.

Therefore, upadacitinib is a potential promising choice for intractable AA accompanied by AD and for patients who resist injection. Previous clinical trials on upadacitinib did not report the occurrence of malignant tumours or opportunistic infections in adolescents. However, a minority of adults taking 30 mg daily of upadacitinib did report malignant tumours, although all events were confirmed less than 3 months after taking the first dose of upadacitinib (12). Further investigations are thus warranted to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in childhood AA.

In conclusion, we report here a paediatric case with AA and AD, treated successfully with upadacitinib for the first time. This case report provides evidence for the use of low dosage of upadacitinib in the management of concurrent childhood AA/AD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her parents for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 81872520).

REFERENCES

- Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, Hua T, Rastogi S, Ibler E, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: 675–682.

- Andersen YM, Egeberg A, Gislason GH, Skov L, Thyssen JP. Autoimmune diseases in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 274–280.e1.

- Barton VR, Toussi A, Awasthi S, Kiuru M. Treatment of pediatric alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022; 86: 1318–1334.

- Lensing M, Jabbari A. An overview of JAK/STAT pathways and JAK inhibition in alopecia areata. Front Immunol 2022; 13: 955035.

- King B, Ko J, Forman S, Ohyama M, Mesinkovska N, Yu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of the oral Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib in the treatment of adults with alopecia areata: phase 2 results from a randomized controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 85: 847–853.

- King B, Ohyama M, Kwon O, Zlotogorski A, Ko J, Mesinkovska NA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 1687–1699.

- Craiglow BG, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata in preadolescent children. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 568–570.

- Asfour L, Getsos Colla T, Moussa A, Sinclair RD. Concurrent chronic alopecia areata and severe atopic dermatitis successfully treated with upadacitinib. Int J Dermatol 2022; 61: e416–e417.

- Cantelli M, Martora F, Patruno C, Nappa P, Fabbrocini G, Napolitano M. Upadacitinib improved alopecia areata in a patient with atopic dermatitis: a case report. Dermatol Ther 2022; 35: e15346.

- Gambardella A, Licata G, Calabrese G, De Rosa A, Alfano R, Argenziano G. Dual Efficacy of upadacitinib in 2 patients with concomitant severe atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Dermatitis 2021; 32: e85–e86.

- Gori N, Cappilli S, Di Stefani A, Tassone F, Chiricozzi A, Peris K. Assessment of alopecia areata universalis successfully treated with upadacitinib. Int J Dermatol 2023; 62: e61–e63.

- Le M, Berman-Rosa M, Ghazawi FM, Bourcier M, Fiorillo L, Gooderham M, et al. Systematic review on the efficacy and safety of oral janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8: 682547.