ORIGINAL REPORT

Expert Recommendations on Facilitating Personalized Approaches to Long-term Management of Actinic Keratosis: The Personalizing Actinic Keratosis Treatment (PAKT) Project

Colin MORTON1, Samira BAHARLOU2,3, Nicole BASSET-SEGUIN4,5, Piergiacomo CALZAVARA-PINTON6, Thomas DIRSCHKA7, Yolanda GILABERTE8, Merete HAEDERSDAL9, Günther HOFBAUER10, Sheetal SAPRA11,12, Rick WAALBOER-SPUIJ13, Leona YIP14 and Rolf-Markus SZEIMIES15

1Department of Dermatology, NHS Forth Valley, Stirling, UK, 2Department of Dermatology, Skin Immunology & Immune Tolerance (SKIN) Research Group, Vrije Universiteit Brussel , Brussels, Belgium, 3Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Brussels, Belgium, 4Université de Paris, Paris, France, 5Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France, 6Dermatology Department, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy, 7CentroDerm Clinic, Wuppertal, Germany, 8Department of Dermatology, Miguel Servet University Hospital, IIS Aragón, Zaragoza, Spain, 9Department of Dermatology, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospitals, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark, 10University Hospital Zürich, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, 11Oakville Trafalgar Memorial Hospital, Oakville, Canada, 12Institution of Cosmetic and Laser Surgery, Oakville, Canada, 13Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 14Skin Partners, Brisbane, Australia and 15Department of Dermatology & Allergology, Klinikum Vest GmbH Academic Teaching Hospital, Recklinghausen, Germany

Actinic keratoses are pre-malignant skin lesions that require personalized care, a lack of which may result in poor treatment adherence and suboptimal outcomes. Current guidance on personalizing care is limited, notably in terms of tailoring treatment to individual patient priorities and goals and supporting shared decision-making between healthcare professionals and patients. The aim of the Personalizing Actinic Keratosis Treatment panel, comprised of 12 dermatologists, was to identify current unmet needs in care and, using a modified Delphi approach, develop recommendations to support personalized, long-term management of actinic keratoses lesions. Panellists generated recommendations by voting on consensus statements. Voting was blinded and consensus was defined as ≥ 75% voting ’agree’ or ’strongly agree’. Statements that reached consensus were used to develop a clinical tool, of which, the goal was to improve understanding of disease chronicity, and the need for long-term, repeated treatment cycles. The tool highlights key decision stages across the patient journey and captures the panellist’s ratings of treatment options for attributes prioritized by patients. The expert recommendations and the clinical tool can be used to facilitate patient-centric management of actinic keratoses in daily practice, encompassing patient priorities and goals to set realistic treatment expectations and improve care outcomes.

Key words: actinic keratoses; consensus; Delphi study; squamous cell carcinoma; surveys and questionnaires; skin cancer.

SIGNIFICANCE

Actinic keratoses are skin lesions that form due to long-term, repeated exposure to the sun. Lesions can progress to squamous cell carcinoma; hence a key treatment goal is to prevent malignant progression. There is limited guidance on personalizing care for individual patients and supporting shared decision-making between physicians and patients to prevent suboptimal treatment outcomes. To support personalized actinic keratoses care, a group of 12 expert dermatologists used e-surveys to generate recommendations and develop a clinical tool. These can be used to guide shared decision-making between patients and healthcare professionals to support optimal, personalized, long-term care.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv6229. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.6229.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Apr 25, 2023; Published: Jun 8, 2023

Corr: Colin Morton, Department of Dermatology, NHS Forth Valley, Stirling, UK. E-mail: colin.morton@nhs.scot

Competing interests and funding: Panel members were invited by Galderma, who funded the planning and delivery of this project.

All panel members received honoraria from Galderma for participating in this project. CM is a board member for The European Society for Photodynamic Therapy, has acted as an advisory board member for Almirall and Galderma, and has acted as an investigator for Galderma and LEO Pharma. SB has acted as an advisory board member and received speaker fees and travel grants from Almirall and Galderma. NB-S has acted as a consultant for Almirall and Galderma. PC-P has acted as an advisory board member for AbbVie, Almirall, Cantabria, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Molteni and Sanofi, has received grants for talks from Almirall, AbbVie, Novartis, LEO Pharma, Sanofi, Novartis, and has acted as an investigator for Clinuvel, Mitsubishi, Novartis, Sanofi, Galderma, LEO Pharma, Amgen, Biogen, Pierre-Fabre, Regeneron, and SI Health. TD has received grants/research support from Almirall, Biofrontera, Galderma, Meda, and Schulze & Böhm, has lectured for Almirall, Biofrontera, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, infectopharm, LEO Pharma, Meda, Neracare, Novartis, Janssen-Cilag, and Riemser, and has acted as an advisory board member for Almirall, Biofrontera, Dr. Pfleger, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, LEO Pharma, Meda, Neracare, Novartis, and Scibase. YG has acted as consultant and/or researcher for Almirall, Galderma, Isdin, Roche Posay, AbbVie, Pfizer, IFC Cantabria, Sanofi and Lilly. MH has received equipment from Cherry Imaging, Cynosure, Lutronic, Mirai Medical, miraDry, PerfAction Technologies, Venus Concept, has received research grants from LEO Pharma, Lutronic, Mirai Medical, Studies&Me, Venus Concept, and has lectured for Galderma Nordic and Sanofi. GH has received research support from the Swiss National Fund, has acted as a speaker for AbbVie, Galderma Spirig, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Louis Widmer, MEDA, Merck, Novartis, Permamed, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi Genzyme, and acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, Biofrontera/Louis Widmer, Galderma Spirig, Hoffmann-La Roche, LEO Pharma, MEDA, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme. SS has acted as a consultant, clinical trials investigator and advisory board member for Galderma. RW-S reports no conflicts of interest. LY has acted as a consultant/key opinion leader for Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, L’Oréal Australia, and Novartis, and has acted as an advisory board member for Lilly. R-MS has acted as an advisory board member for AbbVie, Almirall, Dr. Wolff Group, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, photonamic, and Pierre-Fabre, has received grants and/or honoraria from ALK, Almirall, Beiersdorf, Galderma, Janssen, Knappschaft, Novartis, and has acted as an investigator for Dr. Wolff Group, Galderma, LEO Pharma, and photonamic.

INTRODUCTION

Actinic keratoses (AK) are common, pre-malignant skin lesions caused by long-term, repeated exposure to the sun, resulting in genetic changes that lead to damaged epidermal keratinocytes within a field of photodamaged skin (1, 2). Over time, skin presents with single or multiple visible erythematous lesions of varying thickness surrounded by areas of non-visible, subclinical damage, known as the field of cancerization (3). Lesions have the potential for malignant transformation to in-situ and invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (4). The natural progression of lesions is variable, and it is difficult to accurately predict progression to SCC (5, 6), given that there are currently no established clinical biomarkers that can predict this change. Therefore, the long-term, repeated treatment and management of evolving visible lesions, and the surrounding field, is crucial to prevent lesion recurrence and potential progression to malignancy (2, 6, 7).

Aside from the fear of developing skin cancer and obvious cosmetic changes, patients with AK experience chronic itching, burning and tenderness of their skin, significantly impairing their wellbeing and ability to live a ’normal’ life (8, 9). These physical and psychological symptoms can have a greater negative impact on quality of life (QoL) for patients with severe AK vs mild disease, and QoL for patients with severe disease is comparable to patients with psoriasis and eczema (9).

Personalized care plays an important role in chronic skin conditions, where treatment success is highly dependent on patient adherence to long-term, repeated treatment regimens (10, 11). To deliver personalized care, healthcare professionals (HCPs) can align with their patients from the beginning of their diagnosis to understand their individual priorities, concerns, and manage their treatment expectations (11). Given the life-long nature of AK and the need for repeated treatment courses, maintaining ongoing, shared decision-making between patients and HCPs can support adherence and optimize treatment outcomes to ultimately improve patient satisfaction and QoL (8, 10, 12).

Personalizing care of AK is limited in two notable areas – firstly, the guidance is unclear on managing certain patient groups who are at elevated risk of AK development and progression to SCC (e.g. organ transplant recipients) (13) or who may not be good candidates for or have suboptimal responses to certain treatments (14). Secondly, guidance does not fully address the disease’s life-long nature and the need for repeated, ongoing management and good patient adherence following diagnosis. Appropriate AK management plans must involve tailored treatment according to patient-specific factors, such as age, comorbidities, and previous skin cancer history (13).

The Personalizing Actinic Keratosis Treatment (PAKT) panel was established to further explore unmet needs in AK care and develop expert recommendations to support the comprehensive, personalized, long-term management of AK throughout the patient journey.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PAKT expert panel

PAKT was established by Galderma to evaluate care for patients with mild/moderate AK on the face and scalp. The PAKT panel comprised 12 expert dermatologists from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland and UK. Two chairpersons from the panel oversaw the process and were involved in panel selection and Delphi design.

Modified Delphi process

A modified Delphi process, consisting of a series of four e-surveys conducted between November 2021 and August 2022, was used to reach consensus on questions pertaining to personalized AK management. To inform and direct e-survey content, an initial literature search was conducted to identify gaps and unmet needs in current recommendations for AK management. Search results were reviewed by both chairpersons and shared with the panel prior to the first e-survey. Full literature search methodology and results are available in Appendix S1.

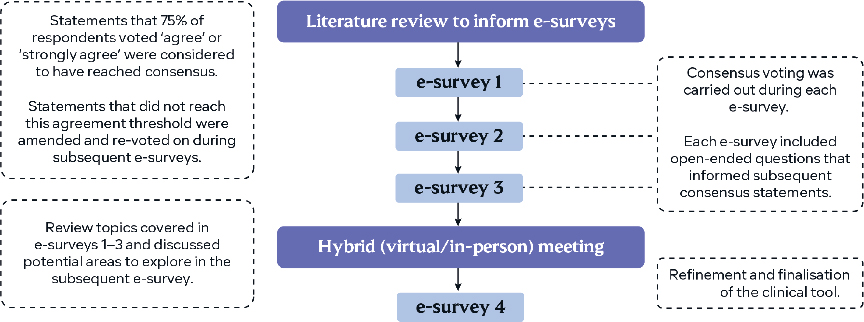

Survey responses were collated to generate consensus recommendations used to develop a clinical management tool for patient-centred care and shared decision-making throughout the AK journey. The tool was refined over a hybrid (virtual/in-person) meeting with the PAKT panel (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The modified Delphi process used by the Personalizing Actinic Keratosis Treatment panel.

E-survey development and administration

Consensus statements were structured to assess the level of agreement using the following response range: ’strongly disagree’, ’disagree’, ’agree’, ’strongly agree’ or ’abstain/unable to answer’. Consensus was defined as ≥ 75% voting ’agree’ or ’strongly agree’. Some questions were posed as multiple-choice, where several responses could be selected, for which results are presented as consensus when chosen by ≥ 75% of panellists. Open-ended questions were included to allow for the development of statements in a subsequent round of voting. Statements that did not reach consensus were rephrased and then revoted on in subsequent surveys. Panellists could also input free-text responses to explain their answer choices.

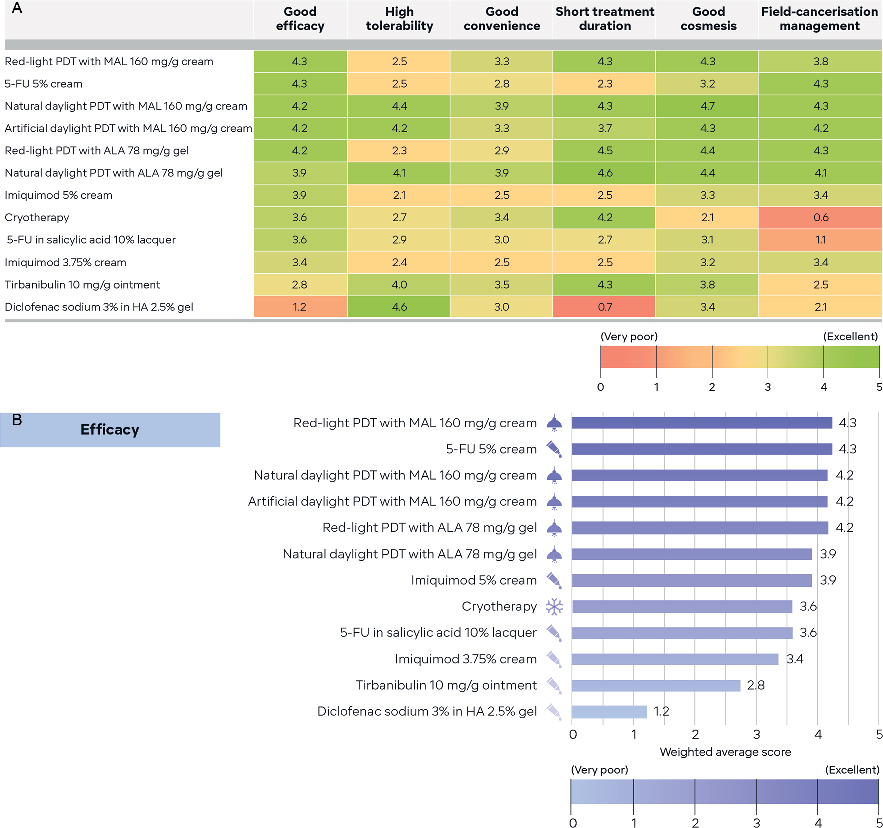

In the third e-survey, delivered in March 2022, panellists ranked AK treatment options for six different attributes using a 6-point scale. Weighted mean scores for the rankings were used to develop treatment option schematics to support shared decision-making in practice.

An interim hybrid panel meeting was conducted after e-surveys 1–3 to review topics covered in these surveys and discuss potential areas to explore in the subsequent final, fourth survey.

The programming, administration, and response collation of the e-surveys was performed by Ogilvy Health, London, UK to maintain blinding. Ogilvy Health UK did not participate in the panel. The key topics investigated included the evolution of AK once photodamage has been observed, patient treatment preferences, and managing patients at high risk of AK progression to SCC.

Patient validation surveys

To ensure the clinical tool incorporates patient insights on AK management, the panel collected patient feedback via survey questions. Panellists obtained oral consent from their patients for their participation, and then discussed each question with them and noted their responses. Full patient validation survey methodology and results are available in Appendix S1.

RESULTS

Definition of consensus recommendations

Consensus statement voting results are given in parentheses (e.g. 11/12 voted ’agree’ or ’strongly agree’). All 12 experts completed the four e-surveys, and the voting results presented are from all of the surveys. Full consensus statement voting results are available in Appendix S1.

Gaps and challenges in actinic keratosis guidelines and research

The PAKT panel identified several gaps in current clinical guidelines for the delivery of personalized, long-term care. The panel noted guidelines:

- Have limited consideration for patient priorities and treatment goals (12/12)

- Do not offer practical ways to account for patient-specific factors (10/11)

- Do not address the chronic nature of AK (11/12)

- Provide limited guidance for managing poor patient adherence (12/12) and selecting preventive AK treatments (e.g. sun protection) (11/12)

Panellists expressed that treatment follow-up approaches can be inadequate, due to clinical trials not capturing the reality of AK disease chronicity. Trial endpoints may be too short to fully account for lesion recurrence, which may contribute to the paucity of long-term treatment efficacy data.

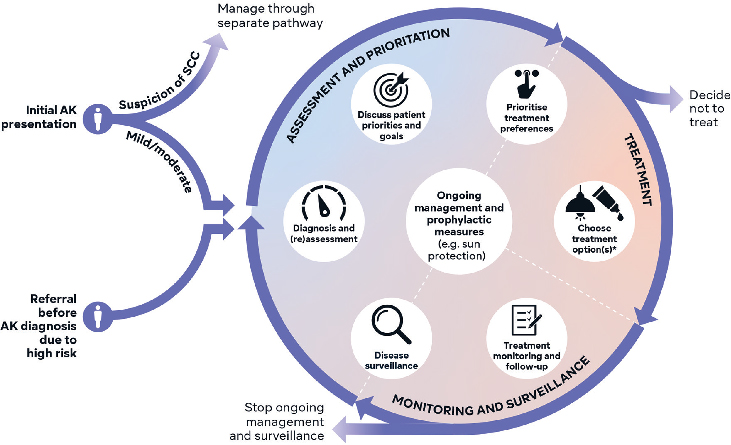

Overview of the patient journey flowchart

Key points in the patient journey for mild/moderate AK on the face and scalp were identified and mapped out into a flowchart diagram (Fig. 2). The panel focussed on mild/moderate disease, given the lack of guidance on personalizing care and selecting treatment for this large patient cohort. For patients with severe disease and suspected SCC, a separate referral path is indicated at the start of the patient journey to fast-track these patients.

Fig. 2. Overview of a patient journey flowchart for the management of mild/moderate actinic keratosis (AK) on the face and scalp. Based on consensus recommendations and discussion from the Personalizing Actinic Keratosis Treatment panel of experts. Two entry points lead to seven key decision stages in the circle component, which are arranged within three domains. Arrows indicate the flow from one decision stage to the next. *Including co-prescriptions and adjunctive therapies. SCC: squamous cell carcinoma.

Two ’entry points’ (’Initial AK presentation’ and ’Referral before AK diagnosis due to high risk’) lead to seven key decision stages in the circle component arranged by ’Assessment and Prioritisation’, ’Treatment’, and ’Monitoring and Surveillance’. The circular design and flow indication with arrows can support communication of the AK journey to patients and HCPs as a chronic disease requiring repeated cycles of treatment and follow-up.

Assessment and prioritization

Establishing goals and setting realistic expectations prior to treatment initiation can help drive personalized decision-making from the beginning of the patient journey. Goals of AK treatment that reached consensus were primarily focused on limiting lesion development, recurrence and progression. The complete list of goals is shown in Table SI.

Goals were prioritized differently for patients at high risk of developing AK and subsequent SCC and included:

- Reducing the risk of progression to SCC (12/12)

- Clearing/controlling the field of cancerization (10/12)

- Reducing the impact of the disease on the patient (9/12)

Panellists noted goals fluctuate for patients at high risk, depending on their treatment stage; patients requiring additional treatment rounds for their comorbidities may be more likely to deprioritize cosmetic AK treatment goals (e.g. improving skin appearance). Consideration of how treatment goals change as the patient’s other comorbidities progress may impact treatment personalization.

Prior to treatment initiation, it is also important to set realistic expectations of treatment outcomes with patients (11/12). Factors important to discuss for setting expectations are provided in Table SII.

Treatment

Once patient priorities, goals, and preferences have been established, the next step in the AK management journey is to select treatment. Determining suitable treatment for an individual patient requires consideration of multiple factors (e.g. comorbidities (10/12)) and the treatment itself (e.g. treatment frequency (9/12)). More factors are provided in Table SIII.

When selecting treatments for patients at high risk of developing AK and subsequent SCC, consideration should be given to:

- Treatment modality (12/12)

- Frequency (11/12) of follow-up required

- Duration (9/11) of follow-up required

The panel gave particular consideration to immunosuppressed patients, who have a higher risk of developing AK vs immunocompetent patients. Factors more relevant for immunosuppressed patients include:

- The need to treat the field of cancerization rather than individual lesions (12/12)

- Treatments with demonstrated efficacy (12/12) and safety (10/12) profiles in immunosuppressed patients

- The number of AK lesions (9/12)

To aid treatment selection, AK treatment options were rated based on published evidence and the panel’s own clinical experience. Treatments were rated for factors important to patients: good efficacy, high tolerability, good convenience, short treatment duration, good cosmesis and field-cancerization management. Weighted mean scores for rankings were collated and presented as treatment option schematics (Fig. 3a, b). These scores are not intended to act as a substitute for evidence-based recommendations in clinical guidelines or indicate which treatments are suitable for first-, second- or third-line treatment, but rather, they are a guide for making treatment decisions with patients in practice.

Fig. 3. Treatment option schematics based on panellist treatment attribute ratings. Panellists rated actinic keratosis (AK) treatment options based on combined knowledge from clinical evidence and their own clinical experience by answering the following question: ’Consider the treatments below. Based on your combined knowledge from clinical evidence (which includes published real-world evidence) and your own clinical experience, please rate each treatment on a scale from 0 (very poor) to 5 (excellent) for the listed factors.’ Factors rated were: good efficacy, high tolerability, good convenience, short treatment duration, good cosmesis and field-cancerization management. Weighted mean scores for the treatment attribute rankings were collated and designed as treatment option schematics. (A) Red/green gradient heatmap, with treatments ranked by efficacy rating. (B) Stacked bar chart showing efficacy ranking. ALA: aminolaevulinic acid; FU: fluorouracil; HA: hyaluronic acid; MAL: methyl aminolevulinate; PDT: photodynamic therapy.

The panel evaluated the schematic’s strengths and weaknesses and considered how they could be used by different audiences. For patient consultations and teaching purposes, a red/green heatmap (Fig. 3a) was selected, with treatments ordered by efficacy rating providing an overview of all the treatment option attribute ratings. Additionally, the simplified level of detail was noted as having potential good usability with patients. Panellist’s believed dermatologists and primary care physicians could utilize stacked bar charts (Fig. 3b) for directly comparing treatments side‑by-side for any given rated attribute to help select treatment. It was noted the ordered rating of the different bars facilitates identification of the highest and lowest scoring treatments for any of the rated attributes.

Monitoring and surveillance

A patient-tailored, ongoing management strategy may help limit new lesion development and achieve optimal treatment outcomes. The panel identified important considerations for scheduling treatment follow-up appointments and when disease surveillance following treatment should be carried out. Some panellists commented that current follow-up schedules should reflect the chronic nature of AK and be comparable in frequency and duration to schedules established for patients with melanoma.

The key goals for the ongoing management of an individual patient include preventing further photodamage (12/12) and new AK development (12/12). Factors involved in ongoing management are provided in Table SIV.

At completion of treatment follow-up, the decision to carry out appointments for ongoing disease surveillance specifically is influenced by:

- Previous non-melanoma skin cancer history (12/12)

- Immunosuppression status (12/12)

- Disease severity (10/12)

During treatment follow-up appointments multiple factors are taken into consideration to determine treatment success, including:

- Reduction in visible AK lesion number (11/12)

- Clearance of field cancerization (11/12)

- The patient’s treatment goals being achieved (10/12)

- Reduced follow-up appointment frequency after field-directed treatments (9/12)

Elements of management relevant throughout the patient journey

Given the chronic, recurrent nature of AK, some aspects of management persist throughout the patient journey once a diagnosis has been established.

To prevent further photodamage and limit new lesion development, sun protection measures (e.g. sunscreens) should be:

- Used for post-treatment adjunctive therapy (12/12)

- Used throughout the AK journey (12/12)

- Regularly evaluated when individualizing care for patients (10/12)

Sun protection measures include the use of protective clothing, sun-avoidant behaviour, and the use of sunscreens. The effective characteristics of sunscreens identified were:

- Sun protection factor (SPF) > 30 (12/12)

- The presence of long-term clinical data in patients at high risk (e.g. organ transplant recipients) (9/12)

- Long durability of application (9/12)

- Sweatproof/waterproof (9/12)

- Easily applicable (9/12)

Panellists noted that education can support the understanding of AK as a chronic disease requiring lifetime disease surveillance and repeated, ongoing management. Delivery of patient education tailored to each individual patient’s needs can support the setting of realistic expectations prior to treatment initiation and throughout the AK patient journey.

Effective patient education would be useful for formulating a personalized AK management plan (9/12) where good understanding of AK disease chronicity can support optimal treatment outcomes (12/12). In addition, patient-centric education can overcome barriers to AK treatment (12/12), including:

- Local skin response (11/12)

- Treatment-related side-effects (10/12)

- Poor disease awareness (10/12)

- Inadequate adherence (9/12)

The most effective communication channels for educating patients with AK about their condition and its management include dermatologist–patient discussions (12/12) and visual aids for use by HCPs (e.g. clinical pictures/diagrams) (11/12).

DISCUSSION

A panel of expert dermatologists identified the need for improved patient-centric management of AK and generated recommendations to facilitate personalized care. Given both the physical and psychological impact of AK on QoL, especially for those with severe disease and higher associated risk of SCC (8, 9), personalized, long-term care may support optimal treatment outcomes.

The panel identified that current clinical practice guidelines provide limited guidance for patient-centric AK care and considering individual goals and priorities, which may negatively impact outcomes. Some guidelines consider factors, such as age and patient preference, but are limited in terms of their implications in clinical decision-making (13, 15). By providing practical recommendations that incorporate patient preferences, priorities, and treatment goals, PAKT has supported a potential shift in the AK management focus from clinical or lesion-related considerations (16) to patient-centric care, which can be key to addressing barriers to AK treatment (2).

The PAKT clinical tool developed from the panel recommendations could be used to support a shared commitment to care between HCPs and patients, which has the potential to achieve better outcomes and greater patient satisfaction (10). This may combat non-adherence to treatments associated with poor responses and worse disease outcomes (17). The recommendations support the need for HCPs to explore patient well-being and concerns, which can be a core dimension of expert dermatological care and an expectation of HCP–patient interactions (10). Patient validation responses highlighted how individual patients have different priorities and goals of treatment, which may vary compared with physician perspectives. This further reinforced the importance of personalized care where the patient is evaluated as an individual and is given an active role in decision-making.

The tool captures the chronic, cyclical nature of AK management and is designed to foster shared decision-making between HCPs and patients at each stage, allowing for the mutual determination of treatment goals and priorities. Treatment option schematics support treatment selection based on rated attributes that matter to patients: good efficacy (18–20), high tolerability (18, 20, 21–23), short treatment duration (19, 24, 25), good convenience (22, 23) and cosmesis (2), and field-cancerization management (26). PDT modalities scored highly across these attributes, aligning with the high patient preference for this treatment method seen in clinical trials (21). It is important to note that the clinical tool is not intended to act as a substitute for clinical guidelines, or advise on specific treatment recommendations, but is proposed to optimize the process of care in clinical practice.

The tool could be utilized in settings beyond the clinic. As poor disease awareness is a key barrier to good AK treatment outcomes (2), the panel recognized the tool’s value in educational settings to support both HCP and patient education on disease chronicity and the need for repeated, ongoing management to manage disease progression. Further tool developments could focus on use within a patient-centric framework (2) and tailored for point-of-care HCPs (e.g. primary care physicians) to deliver effective patient education when patients are first diagnosed with AK (8). The panel noted that this could be achieved through the development of communication points for HCPs to help explain the life-long nature of AK, lesion progression to SCC, and the need for repeated cycles of treatment.

Panel input on the management and follow-up of AK accounted for disease chronicity and recognized changes to treatment approaches required for patients at high risk of developing AK and subsequent SCC. The panel defined specific goals for this patient subpopulation not recognized in recent guidelines (15, 27). Given the elevated risk of AK and SCC progression in this patient population, the recommendations help support the need for early and frequent treatment of AK to limit new lesion development and progression to SCC (13, 28–30). Further understanding of how to personalize AK care for different patient groups at high risk (e.g. organ transplant recipients) is still needed, given their increased risk of malignancy and because many conventional AK therapies are often less effective for these patients (30).

An important limitation is that the PAKT recommendations are based primarily on the panel’s experiences and reflect HCP perspectives on AK care, which could potentially differ from patient perspectives. Although the panel attempted to address this limitation by collecting patient insights, these too are HCP-reported. In addition, although the PAKT consensus integrates recommendations from an international group of experts, it only represents the healthcare systems in which the panel has experience and may not account for nuances in other regions, such as product availability, reimbursement, and the individual cost of treatment(s) for patients.

Using a modified Delphi approach, the PAKT panel generated expert recommendations on the personalized, long-term management of AK throughout the patient journey incorporating patient-, disease- and treatment-specific factors that drive treatment selection for the individual patient (31). Given the reported variable approach to AK management, with not all HCPs recognizing the life-long nature of the disease (32), these recommendations and the clinical tool may aid standardized HCP decision-making throughout the management journey. The PAKT panel looks forward to feedback on the use of the clinical tool in practice and insights on possible future applications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Medical writing and administrative support were provided by Shounak De, MPharm, Rachel Byrne, MSc, Farah Issa, BSc, and Victoria Smith, BSc, from Ogilvy Health, London, UK.

IRB approval status

Not applicable

REFERENCES

- Balcere A, Rone Kupfere M, Čēma I, Krūmiņa A. Prevalence, discontinuation rate, and risk factors for severe local site reactions with topical field treatment options for actinic keratosis of the face and scalp. Medicina 2019; 55: 92.

- Cerio R. The importance of patient-centred care to overcome barriers in the management of actinic keratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 17–20.

- Goldenberg G. Treatment considerations in actinic keratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 12–16.

- Siegel JA, Korgavkar K, Weinstock MA. Current perspective on actinic keratosis: a review. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: 350–358.

- Fernandez Figueras MT. From actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma: pathophysiology revisited. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 5–7.

- Cantisani C, De Gado F, Ulrich M, Bottoni U, Iacobellis F, Richetta AG, et al. Actinic keratosis: review of the literature and new patents. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2013; 7: 168–175.

- Filosa A, Filosa G. Actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma: clinical and pathological features. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2015; 150: 379–384.

- Chetty P, Choi F, Mitchell T. Primary care review of actinic keratosis and its therapeutic options: a global perspective. Dermatol Ther 2015; 5: 19–35.

- Tennvall GR, Norlin JM, Malmberg I, Erlendsson AM, Hædersdal M. Health related quality of life in patients with actinic keratosis–an observational study of patients treated in dermatology specialist care in Denmark. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015; 13: 1–9.

- Abbott P. Patient-centred health care for people with chronic skin conditions. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: 329–330.

- Eicher L, Knop M, Aszodi N, Senner S, French LE, Wollenberg A. A systematic review of factors influencing treatment adherence in chronic inflammatory skin disease–strategies for optimizing treatment outcome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 2253–2263.

- Philipp-Dormston WG, Battistella M, Boussemart L, Di Stefani A, Broganelli P, Thoms KM. Patient-centered management of actinic keratosis. Results of a multi-center clinical consensus analyzing non-melanoma skin cancer patient profiles and field-treatment strategies. J Dermatol Treat 2020; 31: 576–582.

- de Berker D, McGregor JM, Mohd Mustapa MF, Exton LS, Hughes BR. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the care of patients with actinic keratosis 2017. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 20–43.

- Richard MA, Amici JM, Basset-Seguin N, Claudel JP, Cribier B, Dréno B. Management of actinic keratosis at specific body sites in patients at high risk of carcinoma lesions: expert consensus from the AKTeam™ of expert clinicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 339–346.

- Heppt MV, Leiter U, Steeb T, Amaral T, Bauer A, Becker JC, et al. S3 guideline for actinic keratosis and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma–short version, part 1: diagnosis, interventions for actinic keratoses, care structures and quality-of-care indicators. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2020; 18: 275–294.

- Poulin Y, Lynde CW, Barber K, Vender R, Claveau J, Bourcier M, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Canada chapter 3: management of actinic keratoses. J Cutan Med Surg 2015; 19: 227–238.

- Shergill B, Zokaie S, Carr AJ. Non-adherence to topical treatments for actinic keratosis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013; 8: 35–41.

- Karrer S, Aschoff RAG, Dominicus R, Krähn-Senftleben G, Gauglitz GG, Zarzour A, et al. Methyl aminolevulinate daylight photodynamic therapy applied at home for non-hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis of the face or scalp: an open, interventional study conducted in Germany. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 661–666.

- Norrlid H, Norlin JM, Holmstrup H, Malmberg I, Sartorius K, Thormann H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in topical field treatment of actinic keratosis in Swedish and Danish patients. J Dermatol Treat 2018; 29: 68–73.

- Vicentini C, Vignion-Dewalle AS, Thecua E, Lecomte F, Maire C, Deleporte P, et al. Photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis of the forehead and scalp: a randomized, controlled, phase II clinical study evaluating the noninferiority of a new protocol involving irradiation with a light-emitting, fabric-based device (the Flexitheralight protocol) compared with the conventional protocol involving irradiation with the Aktilite CL 128 lamp. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 765–773.

- Stritt A, Merk HF, Braathen LR, Von Felbert V. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of actinic keratosis. Photochem Photobiol 2008; 84: 388–398.

- Heron CE, Feldman SR. Ingenol mebutate and the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol 2021; 20: 102–104.

- Perl M, Goldenberg G. Field therapy in the treatment of actinic keratosis. Cutis 2014; 93: 172–173.

- Grada A, Feldman SR, Bragazzi NL, Damiani G. Patient-reported outcomes of topical therapies in actinic keratosis: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther 2021; 34: e14833.

- Diepgen TL, Eicke C, Bastian M. Ingenol mebutate as topical treatment for actinic keratosis based on a prospective, non-interventional, multicentre study of real-life clinical practice in Germany: efficacy and quality of life. Eur J Dermatol 2019; 29: 401–408.

- Regno LD, Catapano S, Stefani AD, Cappilli S, Peris K. Am J Clin Dermatol 2022; 23: 339–352.

- Werner RN, Stockfleth E, Connolly SM, Correia O, Erdmann R, Foley P, et al. Evidence-and consensus-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of actinic keratosis–International League of Dermatological Societies in cooperation with the European Dermatology Forum–short version. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 2069–2079.

- Heppt MV, Steeb T, Niesert AC, Zacher M, Leiter U, Garbe C, et al. Local interventions for actinic keratosis in organ transplant recipients: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 43–50.

- Neidecker MV, Davis-Ajami ML, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR. Pharmacoeconomic considerations in treating actinic keratosis. Pharmacoeconomics 2009; 27: 451–464.

- Basset-Seguin N, Baumann Conzett K, Gerritsen MJP, Gonzalez H, Haedersdal M, Hofbauer GFL, et al. Photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis in organ transplant patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013; 27: 57–66.

- Hofbauer G, Anliker M, Boehncke WH, Brand C, Braun R, Gaide O, et al. Swiss clinical practice guidelines on field cancerization of the skin. Swiss Med Wkly 2014; 144: w14026.

- Noels EC, Lugtenberg M, van Egmond S, Droger SM, Buis PAJ, Nijsten T, et al. Insight into the management of actinic keratosis: a qualitative interview study among general practitioners and dermatologists. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181: 96–104.