ORIGINAL REPORT

Leprosy in French Guiana, 2015 to 2021: Dynamics of a Persistent Public Health Problem

Aurore PETIOT1, Kinan DRAK ALSIBAI2,3, Carmelita DOSSOU1, Pierre COUPPIE1 and Romain BLAIZOT1,4,5

1Dermatology Department, 2Histopathology and Cytology Department, 3Biological Resources Centre, CRB Amazonie, Cayenne Hospital Centre and 4UMR 1019 TBIP, Tropical Biomes and Immunophysiopathology, University of French Guiana, Cayenne, French Guiana and 5Griddist, Research Group for Infectious Dermatology and Sexually Transmitted Diseases, French Society of Dermatology, Paris, France

A resurgence of leprosy as a public health problem in French Guiana was reported over the period 2007 to 2014, particularly among Brazilians gold miners. Prolonged multidrug therapy and reversal reactions represent a therapeutic challenge. The objective of this study was to assess the evolution of leprosy in this European overseas territory. All patients with leprosy confirmed in histopathology between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2021 were included. A total of 86 patients were included, including 64 new cases and 22 previously diagnosed cases. Sixty patients (70%) were male, 6 cases were paediatric. Brazilian gold miners represented 44.1% of reported occupations (15/34). Maroons represented the second community (13 patients, 15%). Multibacillary and paucibacillary forms were found in 53 (71%) and 22 (29%) patients, respectively. The annual prevalence never exceeded the threshold of 1/10,000. The mean incidence and prevalence were significantly lower than during the period 2007 to 2014 (p < 0.0001). Reversal reactions were found in 29 patients and almost always required a long course of steroids. Infliximab allowed a reduction in the length of treatment with steroids in 2/2 cases. In conclusion, the prevalence of leprosy has decreased significantly in French Guiana, but remains driven by the population of illegal gold miners. Anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drugs represent a promising option in the management of reversal reactions.

SIGNIFICANCE

This study recorded 86 patients with leprosy in French Guiana between 2015 and 2021, including 64 new cases. The incidence was significantly lower than during the period 2007 to 2014, suggesting that efforts in detection and treatment were successful. Almost half of these cases were found in illegal Brazilian gold miners work-ing in the forest hinterland. Reversal reactions, immune complications, which lengthen the duration of treatment, were found in 22 patients. In 2 of these patients, a new drug (infliximab) allowed the steroids, which were used to treat the reversal reactions but were associated with side-effects, were stopped.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv6246. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.6246.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Mar 28, 2023; Published: May 5, 2023

Corr: Romain Blaizot, Dermatology Department, Cayenne Hospital Centre, Avenue des Flamboyants, 97300 Cayenne, French Guiana. E-mail: Blaizot.romain@gmail.com

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

INTRODUCTION

Leprosy or Hansen’s disease is caused by the bacillus of the same name (Mycobacterium leprae and M. lepromatosis). It affects the skin and the peripheral nervous system and can cause severe damage if left untreated. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers leprosy as a neglected tropical disease (NTD). Indeed, it benefits from few research resources and preferentially affects poor populations in endemic areas (1). French Guiana is located in South America, between the Brazilian state of Amapa and the Republic of Suriname (former Dutch Guiana). French Guiana is mostly covered by rainforest and harbours numerous autochthonous populations (Amerindians and Maroons), often living in remote villages of the hinterland (2). However, French Guiana belongs to the French Republic and the European Union and benefits from a French health system where most healthcare is free for all citizens. Basic care is also freely available for illegal immigrants when they consult in migrant health centres. Therefore, French Guiana presents a unique mix of South American and European characteristics. Travel by plane and boat between French Guiana and the French mainland is common, and presents a risk of introduction of tropical diseases to Europe.

Over the period 2007 to 2014 and after a sharp decline in the early 2000s, the incidence of leprosy in French Guiana once again crossed the 1/10,000 threshold considered by the WHO as defining a major public health problem (3). In addition, a change in the epidemiology of the disease was observed, with a decreasing proportion of Maroons (descendants of slaves who escaped from the plantations of Suriname and live mainly along the Maroni). On the other hand, a significant increase in cases was observed among Brazilian patients, particularly gold miners living in precarious conditions in the illegal camps in the rainforest (3). This epidemiological shift, along with a reascending incidence, called for a continuous monitoring of the disease circulation in French Guiana. After the 2007 to 2014 assessment (3), a new evaluation throughout the following 7 years is necessary to confirm or infirm these trends.

The objective of this study was to describe the evolution of the epidemiology of leprosy in French Guiana over the period 2015 to 2021, particularly in terms of incidence and affected populations.

METHODS

All confirmed cases of leprosy diagnosed in French Guiana between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2021 were included. Confirmation required the presence of compatible skin lesions and compatible histology on skin biopsy (tuberculoid or histiocytic granuloma with presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) or positive bacteriological examination of dermal fluid. The series included new cases occurring during the study period, as well as patients diagnosed in the previous period (2007 to 2014) and still under treatment in 2015. Patients without a confirmed diagnosis, patients treated abroad, or those with history of leprosy without active disease were excluded.

All patients were treated by the Dermatology Department of the Cayenne Hospital, which is the referral centre for all leprosy patients in French Guiana. Dermatologists from this department perform missions in remote health centres throughout French Guiana, which allows a management of the whole territory. Treatment is freely provided to patients without social insurance, due to special funding by the French Guiana Regional Health Agency (Agence Régionale de Santé de Guyane). All consultations are free.

The following data were collected: age, mother tongue, type of housing, country of birth, professions, comorbidities, presence of sequelae at diagnosis. The type of leprosy was defined according to the latest WHO criteria (4) and the Ridley clinical classification (5).

Regarding therapeutic management, the following data were collected: anti-leprosy regimen used, duration of treatment, presence of a leprosy reaction, specific treatment used against the reaction, and its duration.

χ2 test comparison of incidence and prevalence over the periods 2007 to 2014 and 2015 to 2021 were calculated using Python software 3.10.4 (Python Software Foundation; https://www.python.org).

This study was declared on Health Data Hub with the accession number F20220503182816. Non-opposition was collected from all patients. According to French law, no further legal clearance was needed.

RESULTS

In total, 86 patients were included (26 females and 60 males, sex ratio M/F = 2.3) during the study period. The mean age of patients at diagnosis was 43 years (range 3–72 years). Six patients were under 18 years old (7%), including 3 cases under the age of 15 years.

Regarding the country of origin, 78 patients (90%) were born abroad, including 51 (59%) in Brazil and 4 from Haiti (4.6%). Patients with first languages other than French or Guianese Creole included 13 Maroon patients (15%), 4 English-speaking patients from Guyana (4.6%) and 2 Hmong speakers (2.3%). Only 8 patients were born in France, including 7 in French Guiana and 1 in metropolitan France. Gold miners represented 44.1% of the occupations reported (15/34). Socio-demographic characteristics are shown in detail in Table I. Only 1 native American patient had leprosy during the study period.

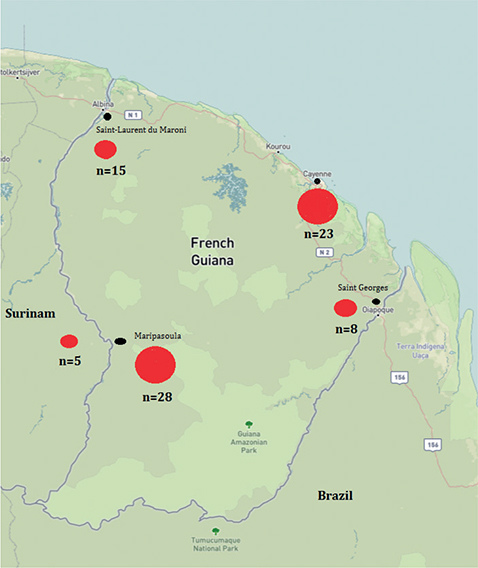

Regarding the geographical distribution, more than half of the patients (48 patients, 55.8%) lived along the Maroni River, including 28 (32.6%) from the Maripasoula region, 15 (17.4%) from the Saint-Laurent urban area, and 5 (5.8%) from Suriname. Patients living in the Cayenne (capita city) metropolitan area comprised 26.7% of cases (23 patients), while those living around Saint-Georges in the East comprised only only 9.3% (8 patients) (Table I). The geographical distribution of cases is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Geographical distribution of leprosy cases in French Guiana, 2015 to 2021, shown for 85/86 cases with known origin (base layer available at https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/topoview/viewer/#8/3.807/-52.721).

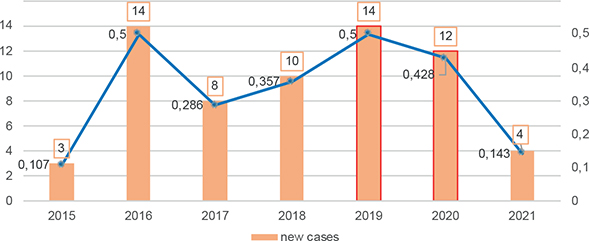

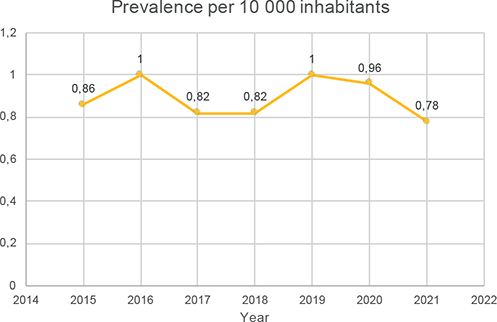

Regarding the incidence and prevalence of leprosy, 64 new cases were diagnosed during the study period, while 22 other patients were followed for previously diagnosed leprosy. The mean annual prevalence was 0.9/10,000 inhabitants. The mean annual incidence rate was 0.33 per 10,000 inhabitants, with an mean of 9 new patients per year (Table II and Fig. 2). The annual prevalence ranged from 0.78 to 0.99/10,000 inhabitants in 2015 to 2021 (Table II and Fig. 3). The prevalence over the study period was therefore less than 1.

| Years | Population* | New cases | Incidence | Prevalence |

| 2015 | 259,865 | 2 | 0.08 | 0.89 |

| 2016 | 269,352 | 14 | 0.52 | 0.97 |

| 2017 | 268,700 | 8 | 0.30 | 0.82 |

| 2018 | 276,128 | 10 | 0.36 | 0.83 |

| 2019 | 281,678 | 14 | 0.50 | 0.99 |

| 2020 | 286,032 | 12 | 0.42 | 0.94 |

| 2021 | 290,528 | 4 | 0.14 | 0.76 |

| *Population assessed according to the French National Institute for Statistics (INSEE). | ||||

Fig. 2. Annual incidence for 10,000 inhabitants and new cases of leprosy diagnosed in French Guiana, 2015 to 2021.

Fig. 3. Annual prevalence of leprosy in French Guiana, 2015 to 2021.

χ2 test comparison of incidence and prevalence over the periods 2007 to 2014 (mean incidence 1.01/10,000, mean prevalence 0.88/10,000) and 2015 to 2021 (mean incidence 0.67/10,000, mean prevalence 0.33/10,000) showed a highly significant decrease (p < 0.0001).

Clinical and biological data of the 86 patients are shown in Table III. Eleven patients had a WHO grade 2 disability” throughout the document at diagnosis. Among them, 9 (82%) were Brazilian. Regarding the treatment, 72 patients received multi-drug therapy (MDT). Seven patients (8.2%) received dual therapy for tuberculoid leprosy before 2017 (4, 6, 7). Two patients had serious side-effects, including 1 case of severe cardiac arrhythmia disorder under clofazimine and 1 case of haemolytic anaemia under dapsone.

| Patients n (%) | |

| Type of leprosy | |

| T | 17 (19.8) |

| BT | 19 (22) |

| BB | 10 (11.6) |

| BL | 16 (18.6) |

| L | 18 (21) |

| Neurological damage only | 1 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 5 (5.8) |

| Bacillar Index (according to WHO criteria) | |

| PB | 23 (26.7) |

| MB | 53 (61.6) |

| Undetermined | 10 (11.7) |

| Treatment | |

| RMP-CMZ-CLA | 38 (44.1) |

| RMP-CMZ-DDS | 31 (36) |

| RMP-DDS-CLA | 2 (2.3) |

| RMP-CMZ-MIN | 1 (1.2) |

| Bitherapy (RMP-CMZ, RMP-DDS, RMP-CLA) | 7 (8.2) |

| Lost before initiation | 7 (8.2) |

| Treatment durationa | |

| 6–12 months | 4 (10) |

| 12–24 months | 18 (46) |

| 24–36 months | 4 (10) |

| > 36 months | 1 (2.5) |

| an = 39, excluding lost to follow-up and patients still undergoing treatment. | |

| RMP: rifampicin; CMZ: clofazimine; DDS: dapsone; CLA: clarithromycin; MIN: minocycline; T: tuberculoid; BT: borderline tuberculoid; BB: borderline borderline; BL: borderline lepromatous; L: lepromatousWHO: World Health Organization. | |

The mean duration of MDT was 13.7 months with a minimum of 1 month (patient lost to follow-up) and a maximum of 50 months. The WHO recommended duration of treatment was exceeded for 12 patients (14%) with paucibacillary forms and 21 patients (24.4%) with multibacillary forms. A treatment interruption before the completion of MDT course was recorded for 24 patients (28%), while 12 patients (14%) received no treatment and were lost to follow-up. Thus, only 41 patients received a complete treatment. Nine patients were still being treated in December 2021.

In total, during the study period (before, during or after treatment) 38 patients were, at some point, lost to follow-up (44.2%).

The COVID 19 pandemic disrupted the implementation of patient follow-up, with 13% of patients having their consultations cancelled during lockdown. Leprosy reactions were reported in 30 patients (34%): 20% type 1 and 14% type 2. Type 1 reactions were treated with corticosteroids. The mean duration of corticosteroid therapy was 13.7 months. Only 1 patient underwent surgical neurolysis.

Regarding type 2 reactions or erythema nodosum leprosum, 8 patients out of 12 received corticosteroids. Ten patients received pentoxifylline, 4 of them as first-line treatment and the others for cortisone sparing. Regarding these drugs, pentoxifylline was not efficient and did not allow a shortening of the corticosteroid course. Thalidomide was also used to wean off corticosteroids in a patient with corticosteroid-dependent type 2 reaction. Introduced after 5 months of corticosteroid therapy, it allowed a cessation without recurrence at 6 months.

Infliximab was successfully used in 2 cases. The first patient had type 2 reaction and was cortico-dependent after 20 months of corticosteroid therapy and 2 failed attempts to stop it. Three courses of infliximab (5 mg/kg W0-W1-W6) allowed the interruption of steroids at 12 months. The second patient received 4 courses of infliximab (5 mg/kg W0-W1-W6-W14) after 16 months of corticosteroid therapy for type 1 and 2 reactions with complete interruption of the steroids at 6 months without recurrence.

DISCUSSION

The annual prevalence of leprosy in this study was consistently below the 1/10,000 threshold considered by WHO to mark a major public health problem. The annual prevalence was close to 1.0 for the years 2016 and 2019 (0.96 and 0.99, respectively) and the incidence in these 2 years was also the highest, at 0.5/10,000 (14 new cases/year). The incidence over the period 2015 to 2021 remained consistently lower than the mean rate over the previous period 2007 to 2014 (0.67/10,000). It seems that efforts in on-field dermatology missions in remote areas, community health and active treatment called for in the previous study by Graille et al. (3) have allowed significant improvements in the control of leprosy in French Guiana.

However, the epidemiological shift that was suggested in the previous study (3) was confirmed over the period 2015 to 2021. Indeed, in the past, leprosy mainly affected the Maroons (8). In the current study, the Maroons population represented 15% of the patients, representing a sizable minority, but not the majority, of cases. Although the collection of ethnicity is forbidden under French law, these patients spoke Sranan Tongo or other Bushinengues dialects as their first language, and can therefore be presumed to belong to the Maroon communities. The previous epidemiological update in 2014 showed a shift towards Brazilian patients (8). Indeed, French Guiana shares a long border with Brazil, the country second most affected by leprosy in the world (9). The growth of illegal gold mining in French Guiana in the 2010s was driven mostly by Brazilian workers who dig in small camps in the rainforest areas of the Guianese hinterland.

In the current study, Brazilians accounted for 59% of affected patients, close to the 56% reported between 2007 and 2014 (3) and more than the proportion observed (33.3%) between 1997 and 2006 (8). Therefore, it seems that the role played by the Brazilian immigration in the dynamics of leprosy in French Guiana remains stable. Though it is still unclear if Brazilian gold miners are infected during their stay in French Guiana or during their previous time in Brazil, it seems they seem to remain one of the main targets for disease control and/or eradication in this territory. Due to important barriers in access to healthcare in this population (10), the incidence of leprosy in French Guiana could be underestimated.

It has been shown recently that people engaged in gold mining activities, especially illegal activities, are particularly affected by zoonoses due to the anthropization and disruption of ecosystems that this practice generates in the heart of the Amazon (11). This also raises questions about the potential role of the armadillo as a potential reservoir of leprosy (12). Indeed, it has been shown that zoonotic transmission of M. leprae to humans by 9-banded (Dasypus novemcinctus) and 6-banded (Euphractus sexcinctus) armadillos (13) occurs in the Southern USA (14). These armadillos are also present in South America, and people in some areas hunt and eat them, as has been demonstrated in Brazil (15). Studies are currently under way in French Guiana to establish the potential role played by armadillos in the transmission of leprosy to humans. The occurrence of many cases of leprosy among gold miners could be explained by more contact with armadillos, or possibly by exposure to bacilli found in the soil, which would also infect armadillos.

Only 1 Amerindian patient was recorded during the study period. Leprosy is extremely rare among Amerindians of French Guiana, with only one case among 10,000 inhabitants during the whole period 2007 to 2021. Like their Maroon neighbours, Amerindians have a traditional way of life based on hunting, fishing and slash-and-burn agriculture. They also share common exposures with gold miners living in the same rainforest areas. However, the incidence of leprosy in French Guiana seems much lower in Amerindians than in Maroons or Brazilians. Conversely, in Brazil, native American people are strongly affected by leprosy. This high incidence is attributed mainly to a lack of access to healthcare and to harsh socio-economic conditions (16). Genetic studies have also suggested a higher sensitivity to leprosy in Indigenous peoples of South America. The innate response to leprosy might be affected by specific alleles of immune genes, notably PARK2/PACRG (17, 18). Likewise, the cellular response to this disease could be influenced by a certain number of HLA genes observed in native Americans (19, 20). As Amerindians of French Guiana should be expected to share common genetic features with their Brazilian cousins, this contrasting incidence of leprosy should be explained by better access to healthcare. Indeed, Amerindians in French Guiana benefit from a French universal healthcare system and a network of dedicated health centres in Amerindian settlements.

Regarding geographical distribution, more than half of the patients (48 patients) lived in Western Guiana (Maroni), and only 8 lived in the Eastern region (Oyapock). This trend seems to be confirmed since 1997 (3, 8). The western part of French Guiana is mostly populated by Maroon communities, as well as a significant concentration of Brazilian gold miners in the forest areas (8). Although there are few data on leprosy in Suriname, the occurrence of cases among Maroons in French Guiana suggests that this disease is also prevalent in the same community, on the other side of the border. There is a risk of cases of leprosy being spread via air travel between Suriname and the Netherlands, on the one hand, and French Guiana and mainland France, on the other hand.

The presence of locally acquired cases suggests the persistence of indigenous transmission. Similarly, the presence of paediatric cases and the frequency of multibacillary forms suggest an active circulation of the bacillus. However, there has been a reduction in the number of cases in children under the age of 16 years: 3 were recorded in the current study compared with 11 in the period 2007 to 2014 (3). Minors (< 18 years old) represented 6 patients and were evenly distributed within the populations (2 Brazilians, 2 Surinamese, 2 Guyanese).

Regarding disabilities, 11 patients (13%) presented a stage 2 disability at diagnosis. Among them 9 were Brazilians (82%). These numbers are similar to those observed during the period 2007 to 2014, and highlight the important delay to diagnosis and treatment in Brazilian gold miners (3).

Concerning the treatment of leprosy, the mean duration of treatment in the current study (13.7 months) exceeded the maximum recommended time (21). This increase in treatment duration was mainly related to the complex follow-up of patients. Indeed, 36 patients were lost to follow-up during treatment. It would appear that relapse cases in the current study are mainly due to lack of compliance, access to healthcare and follow-up. In addition, the COVID 19 pandemic disrupted the implementation of patient follow-up, with 13% of patients having their consultations cancelled during lockdown. This pandemic probably also reduced the detection of new cases by reducing the number of screening consultation, Da Paz et al. assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on leprosy diagnosis in Brazil in 2020 (22). Time trend analyses showed a significant reduction in the detection rate of leprosy in the general population. A similar phenomenon might have occurred in French Guiana, where a prolonged lockdown was enforced throughout large parts of 2020 and 2021.

The WHO estimates that leprosy reactions occur with varying frequency and severity and may be present in up to 50% of cases (23). In the current study leprosy reactions were present in one-third of cases. In the current study, the mean duration of corticosteroid therapy in patients with type 1 reaction was 13.7 months. Cortisone-sparing agents used in leprosy reactions include thalidomide (24) methotrexate (25), clofazimine (26) and pentoxifylline. In the current study 10 patients received pentoxifylline, but it allowed a reduction in corticosteroids in only 2 patients.

Regarding new therapies, infliximab and etanercept effectively reduce tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels and have shown impressive clinical responses in erythema nodosum leprosum (27–29). In the current study anti-TNF-α drugs were used in 2 patients and allowed an interruption of corticosteroids. These new therapies seem promising, and deserve further trials.

This study shows that the incidence of leprosy in French Guiana decreased significantly during the period 2015 to 2021. However, its prevalence remains close to the threshold of a major public health problem, motivating increased efforts in prevention. Specific populations, such as children or Brazilian gold miners, should benefit from public health actions. Dermatologists working in mainland France and the Netherlands should be aware of the risk of cases of leprosy imported from French Guiana and Suriname.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the French Guiana Health Regional Agency (Agence Régionale de Santé de Guyane) for their financial support in the control of leprosy in French Guiana.

REFERENCES

- Alemu Belachew W, Naafs B. Position statement: Leprosy: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 1205–1213.

- Epelboin L, Chroboczek T, Mosnier E, Abboud P, Adenis A, Blanchet D, et al. L’infectiologie en Guyane : le dernier bastion de la médecine tropicale française. La lettre de l’Infectiologue 2016; XXXI.

- Graille J, Blaizot R, Darrigade AS, Sainte-Marie D, Nacher M, Schaub R, et al. Leprosy in French Guiana 2007–2014: a re-emerging public health problem. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182: 237–239.

- World Health Organization Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr Mycobact Dis Off Organ Int Lepr Assoc 1966; 34: 255–273.

- Reibel F, Cambau E, Aubry A. Histoire et actualité du traitement de la lèpre. J Anti-Infect 2015; 17: 91–98.

- Sansarricq, Hubert & UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. 2006. Polychimiothérapie contre la lèpre: développement et mise en oeuvre depuis 25 ans. Organisation mondiale de la Santé. [accessed 24/04/2023] Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/69318.

- Domergue V, Clyti E, Sainte-Marie D, Huber F, Marty C, Couppié P. La lèpre en Guyane française: étude rétrospective de 1997 à 2006. Med Trop 2008; 68: 7.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy (Hansen disease) update, 2020: impact of COVID-19 on the global leprosy control. [accessed 24/04/2023] Available from https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/who-wer9636-421-444.

- Douine M, Mosnier E, Le Hingrat Q, Charpentier C, Corlin F, Hureau L, et al. Illegal gold miners in French Guiana: a neglected population with poor health. BMC Public Health 2017; 18: 23.

- Douine M, Lambert Y, Mutricy L, Galindo M, Bourhy P, Saout M, et al. Émergence de zoonoses: l’orpaillage serait-il un facteur favorisant ? Infect Dis Now 2021; 51: S34–S35.

- Oliveira IVP de M, Deps PD, Antunes JMA de P. Armadillos and leprosy: from infection to biological model. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo 2019; 61: e44.

- da Silva Ferreira J, de Carvalho FM, Vidal Pessolani MC, de Paula Antunes JMA, de Medeiros Oliveira IVP, Ferreira Moura GH, et al. Serological and molecular detection of infection with Mycobacterium leprae in Brazilian six banded armadillos (Euphractus sexcinctus). Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2020; 68: 101397.

- Sharma R, Singh P, Loughry WJ, Lockhart JM, Inman WB, Duthie MS, et al. Zoonotic Leprosy in the Southeastern United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21: 2127–2134.

- da Silva MB, Portela JM, Li W, Jackson M, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Hidalgo AS, et al. Evidence of zoonotic leprosy in Pará, Brazilian Amazon, and risks associated with human contact or consumption of armadillos. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12: e0006532.

- Pescarini JM, Teixeira CSS, Silva NB da, Sanchez MN, Natividade MS da, Rodrigues LC, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and temporal trends of new leprosy cases in Brazil: 2006 to 2017. Cad Saúde Pública 2021; 37: e00130020.

- Alter A, Alcaïs A, Abel L, Schurr E. Leprosy as a genetic model for susceptibility to common infectious diseases. Hum Genet 2008; 123: 227–235.

- Mira MT, Alcaïs A, Van Thuc N, Moraes MO, Di Flumeri C, Hong Thai V, et al. Susceptibility to leprosy is associated with PARK2 and PACRG. Nature 2004; 427: 636–640.

- Moet FJ, Pahan D, Schuring RP, Oskam L, Richardus JH. Physical distance, genetic relationship, age, and leprosy classification are independent risk factors for leprosy in contacts of patients with leprosy. J Infect Dis 2006; 193: 346–353.

- Teles SF, Silva EA, Souza RM de, Tomimori J, Florian MC, Souza RO, et al. Association between NDO-LID and PGL-1 for leprosy and class I and II human leukocyte antigen alleles in an indigenous community in Southwest Amazon. Braz J Infect Dis 2020; 24: 296–303.

- Lazo-Porras M, Prutsky GJ, Barrionuevo P, Tapia JC, Ugarte-Gil C, Ponce OJ, et al. World Health Organization (WHO) antibiotic regimen against other regimens for the treatment of leprosy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 62.

- da Paz WS, Souza M do R, Tavares D dos S, de Jesus AR, dos Santos AD, do Carmo RF, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis of leprosy in Brazil: An ecological and population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022; 9: 100181.

- Lèpre/Maladie de Hansen – Prise en charge des réactions et prévention des infirmités. Conseils techniques. 2017. Available from https://www.who.int/fr/publications-detail/9789290227595.

- Sheskin J. Thalidomide in the treatment of lepra reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1965; 6: 303–306.

- Perez-Molina JA, Arce-Garcia O, Chamorro-Tojeiro S, Norman F, Monge-Maillo B, Comeche B, et al. Use of methotrexate for leprosy reactions. Experience of a referral center and systematic review of the literature. Travel Med Infect Dis 2020; 37: 101670

- Pai V. Role of clofazimine in management of reactions in leprosy: a brief overview. Indian J Drugs Dermatol 2015; 1: 5.

- Valentin J, Drak Alsibai K, Bertin C, Couppie P, Blaizot R. Infliximab in leprosy type 1 reaction: a case report. Int J Dermatol 2021; 60: 1285–1287.

- Faber WR, Jensema AJ, Goldschmidt WFM. Treatment of recurrent erythema nodosum leprosum with infliximab. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 739.

- Ramien ML, Wong A, Keystone JS. Severe refractory erythema nodosum leprosum successfully treated with the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor etanercept. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2011; 52: e133–135.