The aim of this study was to detect demographic and clinical factors associated with affective symptoms and quality of life in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. First, one-way analyses of variance and correlations were performed to compare a large set of qualitative and quantitative clinical variables. Three final multivariable regression models were performed, with depression/anxiety subscales and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores as dependent variables, and the factors that were statistically significant on univariate analyses as independent ones. More severe anxiety symptoms and poorer quality of life (p < 0.01) were significantly associated with more severe depressive symptoms. Female sex and disturbed sleep (p = 0.03) were significantly associated with more severe anxiety. Finally, previous treatment with cyclosporine (p = 0.03) or methotrexate (p = 0.04), more severe depressive symptoms (p < 0.01), itch (p = 0.03), impaired sleep (p < 0.01) and perceived severity of dermatological illness (p < 0.01) were significant predictors of low quality of life. This study shows a complex interplay between the severity of atopic dermatitis, poor quality of life and presence of clinically relevant affective symptoms. These results will help dermatologists to identify patients who need psychiatric consultation within the framework of a multidisciplinary approach.

Key words: atopic dermatitis; depression; anxiety; quality of life.

Accepted Sep 8, 2021; Epub ahead of print Sep 13, 2021

Acta Derm Venereol 2021; 101: adv00590.

doi: 10.2340/00015555-3922

Corr: Massimiliano Buoli, Department of Neurosciences and Mental Health, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Via F. Sforza 35, IT-20122, Milan, Italy. E-mail: massimiliano.buoli@unimi.it

SIGNIFICANCE

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic dermatosis with a high impact on patients’ quality of life. This study used questionnaires to better understand the burden of the disease on patients. More severe anxiety symptoms and poorer quality of life (p < 0.01) were significantly associated with more severe depressive symptoms. Female sex and disturbed sleep (p = 0.03) were significantly associated with more severe anxiety. Finally, previous treatment with cyclosporine (p = 0.03) or methotrexate (p = 0.04), more severe depressive symptoms (p < 0.01), itch (p = 0.03), impaired sleep (p < 0.01) and perceived severity of dermatological illness (p < 0.01) were significant predictors of low quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a widespread inflammatory skin disease mediated by immune dysregulation of type 2 T helper cells and characterized by persistent itch and eczematous lesions (1). AD is one of the most frequent diseases of early childhood, with an observed increase in prevalence in the last 4 decades (2). It is estimated that AD affects approximately 20% of children and adolescents (3) and 2.1–4.9% of adults worldwide (4).

In general, onset of AD occurs during early childhood, with spontaneous remission during adolescence (5); however, in a significant number of patients, AD persists and evolves into a lifelong condition associated with a significant social burden (6). Furthermore, patients affected by AD usually report high levels of psychological distress (7). Of note, chronic itch and skin lesions can result in shame, social impairment and sleep deprivation, damaging the quality of life (QoL) of both patients and their caregivers (8). Subjects affected by AD often report frustration regarding their body appearance, and anger regarding the associated disability (9). All of these factors explain why subjects affected by AD are particularly vulnerable to the development of psychiatric conditions and, in particular, to mood and anxiety disorders (10). Of note, a recent meta-analysis reported that the prevalence of depression was higher in people with vs without AD (20.1% vs 14.8%) (11). In addition, subjects affected by AD more frequently report anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation and a poorer QoL than those with other disabling conditions, such as hypertension or diabetes (12).

Different theories were hypothesized to explain the association between psychiatric conditions and AD. Some authors argued that over-activation of innate immunity (e.g. interleukin 1, interleukin 6 and tumour necrosis factor α) may be a shared mechanism underlying the onset both of AD and psychiatric disorders (13, 14). In addition, systemic inflammation driven by AD facilitates permeation of pro-inflammatory cytokines through the blood–brain barrier (BBB) with a consequent abnormal activation of specific neuronal populations involved in emotional and affective regulation (15). The emotional dysregulation may, in turn, negatively affect the clinical course of AD, because mood symptoms increase the reactivity of the immune system, thus contributing to the maintenance of a systemic pro-inflammatory state (16, 17). In this framework some patients with AD may be particularly at risk of developing an affective disorder and they could benefit from psychiatric support (18).

The aim of the current study was to identify the demographic and clinical factors associated with affective symptoms (depression and anxiety) and QoL in patients affected by moderate–severe AD. The results may facilitate dermatologists in identifying patients who may be more susceptible to mood and anxiety disorders.

METHODS

A total sample of 300 patients with moderate–severe AD who were candidates for treatment with dupilumab were included in the current study (19). The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy). All patients were examined and interviewed to collect demographic and clinical information. The following demographic and clinical information were obtained: age, age at onset, serum total IgE (kU/l), eosinophils (103/mm3), serum lactate dehydrogenase (U/l), sex, the presence of classical phenotype (defined as lichenified/exudative flexural dermatitis, almost always associated with head-and-neck eczema and/or hand eczema, where, in this form, a percentage of patients did not present the flexural pattern (approximately 10%) or had involvement of the extensor surface of the limbs or the trunk (approximately 30%)), type of onset (early persistent: onset before 18 years with persistence of disease after 18 years; early relapsing: onset before 18 years with remission and relapsing in adulthood; late onset: onset after 18 years), presence of comorbidities (rhinitis, conjunctivitis, asthma), number of atopic comorbidities, family history of AD, previous treatment with cyclosporine, previous treatment with methotrexate, past administration of systemic steroids, previous administration of phototherapy, type of AD (extrinsic and intrinsic).

The severity of AD was assessed by administration of the Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), numerical rating scale (itch-INRS), Physician Global Assessment (PGA), and Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI). POEM is a scale specifically designed to evaluate AD severity from the patient’s perspective (20). The POEM score ranges from 0 to 28 (3–7: mild, 8–16: moderate, 17–24: severe, and 25–28: very severe AD) (21). The Itch Numeric Rating Scale (score from 0 to 10: the latter corresponding to the worst itch) is a simple 1-item scale to assess the severity of this symptom in patients with a variety of dermatological diseases (22). The PGA evaluates overall AD severity using a 6-point scale (0: clear, 1–2: mild, 3: moderate, 4–5: severe) (23). The EASI is a tool to assess the extension and severity of AD. EASI total score is obtained taking into account the severity of redness, thickness, scratching and lichenification of 4 body regions (head and neck, trunk, upper limbs and lower limbs; range score 0–72, the latter corresponding to the most severe illness presentation) (24).

Severity of anxiety and depression, and psychological well-being were measured by administration of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Sleep Quality Numeric Rating Scale (SQ-NRS). The HADS, largely administered to assess affective symptoms in patients with medical comorbidities, consists of 2 subscales (1 for depression and the other for anxiety), each consisting of 7 items. Scoring for each item ranges from 0 to 3; thus, the total score for each subscale can range from 0 to 21. A score ≥ 8 in each sub-item denotes the presence of clinically significant anxiety and depression (25). The SQ-NRS is a single-item tool to assess the quality of sleep in the past 24 h (where 0 corresponds to the best, and 10 to the worst quality of sleep) (26).

Finally, QoL was assessed with the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI). The DLQI was the first instrument to be created to assess the QoL of patients with skin diseases, and it consists of 10 items (score 0–3) with a potential total score from 0 to 30, this latter score indicating the maximum negative impact of the skin disease on the QoL of patients. A score ≥ 6 indicates at least a moderate negative effect of illness on QoL (27).

Descriptive analyses of the total sample were realized, calculating frequencies for qualitative variables and mean and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative ones. Univariate analyses were performed, comparing HADS anxiety and depression mean total scores and DLQI mean total scores according to qualitative variables (one-way analyses of variance) or quantitative ones (correlations-Pearson’s r). Three multivariate regression models were then performed considering rating scale scores as dependent variables (HADS anxiety and depression sub-scales and DLQI) and factors, resulted to be statistically significant at univariate analyses, as independent ones. These models were replicated using binary logistic regressions and therefore considering the rating scale scores as qualitative variables (HADS anxiety and depression sub-scales score < 8 or ≥ 8 and DLQI score < 6 or ≥ 6).

The level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM, New York, USA).

RESULTS

The total sample included 300 patients: 171 males (57%) and 129 females (43%). Of the participants, 134 (44.6%) and 159 (53.0%) presented, respectively, clinically significant depressive and anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, 272 patients (90.6%) presented at least a moderate negative impact of AD on QoL. Descriptive analyses of the total sample are reported in Table I.

The results of the univariate analyses are summarized in Table II.

The 3 multivariate regression models with statistically significant factors at univariate analyses as independent variables and HADS depression/anxiety and DLQI scores as dependent ones were found to be reliable (Durbin-Watson: HADS depression 1.84, HADS anxiety 2.00, DLQI 2.10).

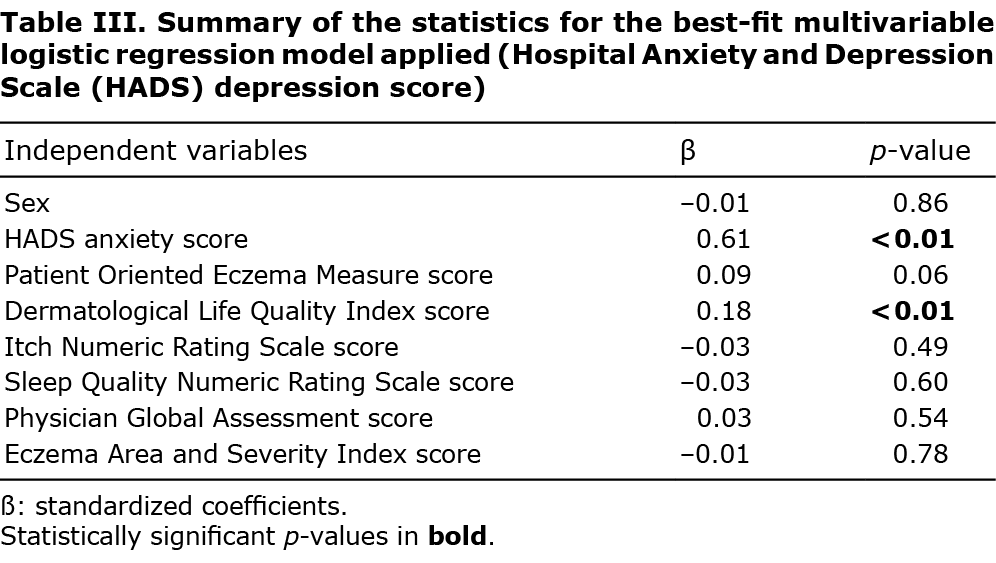

The multivariate regression models revealed that: (i) depressive symptoms were significantly associated with: severity of anxiety (HADS anxiety subscale scores, ß = 0.61, p < 0.01), severity of dermatological disease as perceived by patients at a borderline level (POEM scores, ß = 0.09, p = 0.06) and worse QoL (ß = 0.18, p < 0.01) (Table III); (ii) anxiety symptoms were significantly associated with: female sex (ß = 0.09, p = 0.04), severity of depression (HADS depression subscale score, ß = 0.61, p < 0.01), worse QoL at a borderline level (ß = 0.10, p = 0.06) and poor sleep quality (ß = 0.11, p = 0.03) (Table IV); (iii) poor QoL was significantly associated with: previous treatment with cyclosporine (ß = 0.10, p = 0.03), previous treatment with methotrexate (ß = 0.09, p = 0.04), severity of depression (HADS depression subscale score, ß = 0.23, p < 0.01), severity of dermatological disease as perceived by patients (POEM scores, ß = 0.20, p < 0.01), severity of itch (INRS score, ß = 0.11, p = 0.03), poor quality of sleep (SQ-NRS score, ß = 0.21, p < 0.01), severity of dermatological illness as observed by the dermatologist at a borderline level (PGA score, ß = 0.09, p = 0.06) (Table V).

Binary logistic regression analyses confirmed most of the results of the multivariate regression models and, specifically, that: severity of anxiety symptoms (odds ratio (OR) 1.51, p < 0.01) and poor QoL (OR 1.06, p = 0.04) were significantly associated with clinically relevant depressive symptoms; female sex (exponential B coefficient-Exp B 2.15, p = 0.01) and severity of depressive symptoms (OR 1.51, p < 0.01) were significantly associated with clinically relevant anxiety symptoms; previous treatment with cyclosporine (Exp B=3.82, p = 0.02), severity of AD as perceived by patients (POEM scores) (OR 1.14, p < 0.01), severity of depressive symptoms (OR 1.25, p < 0.01) and poor quality of sleep (SQ-NRS score) (OR 1.24, p = 0.01) were all factors significantly associated with compromised QoL.

DISCUSSION

Approximately half of the patients included in this study showed clinically relevant anxiety and depressive symptoms, confirming that mental health is a relevant topic in dermatology and, specifically, in the treatment of AD (28). This figure is impressive if we consider that, in general population, the point prevalence of depression and 1-year prevalence of clinically significant anxiety symptoms are, respectively, 12.9% (29) and 10.6% (30). Furthermore, to the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the few studies aimed at identifying the factors associated with poor mental health (affective symptoms) and concomitantly low QoL in a relatively large sample of patients affected by AD.

These data confirm that depression is responsible for low QoL in subjects affected by AD. This is not surprising, as depressive symptoms negatively impact the social functioning of patients affected by several chronic medical diseases, including those characterized by immune dysfunction (30), such as AD. In agreement with the current results, the contribution of mood symptoms to poor QoL of patients with AD was confirmed by other studies conducted in different geographical areas (32–34). Furthermore, the current data confirm that the severity of the dermatological disease as perceived by patients can exacerbate depressive symptoms due to the stigma deriving from the dermatological lesions and the consequent anxiety (35). Anxiety, in turn, as confirmed by the current results, is an important factor associated with depressive symptoms, reproducing the vicious circle that links affective symptoms, perceived dermatological severity and poor QoL (36).

The current study found that women with AD are more vulnerable to anxiety symptoms. This aspect can be explained by sex differences in biological regulation of emotions and stress responses (37), but also by the fact that women are probably more vulnerable to stigma, social rejection, and feelings of shame as a result of skin lesions compared with men (38). Women are also more likely to express their emotions and seek support from mental health professionals (39, 40). In addition, poor quality of sleep was found to be a predictor of anxiety symptoms, which is not surprising, as anxiety disorders are frequently associated with changes in circadian rhythms and early insomnia (16). Of note, in agreement with the current results, 2 recent studies reported sleep impairment in a wide number of patients with AD, and described it as an important factor associated with anxiety (41, 42).

Finally, it is not surprising that QoL was found to be compromised by depressive symptoms, as mood symptoms cause a worsening of functioning in different aspects of life, including work and social relations (43). Similarly, poor quality of sleep and severe persistent itch is expected to disrupt activities of daily living (44). Subjective perception of the severity of AD more than the objective evaluation by a dermatologist seems to worsen QoL, probably as a result of the fear of social rejection and marginalization due to skin lesions and symptoms, such as continuous itch (44). Previous treatment with cyclosporine or methotrexate seems to worsen QoL, probably for the adverse events associated with these 2 drugs. Of note, administration of cyclosporine is associated with troublesome side-effects, such as gum enlargement, and with an increased cardiovascular risk due to hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia (45). Similarly, treatment with methotrexate frequently requires an adjustment of doses as a result of related gastrointestinal side-effects (46). Furthermore, a history of numerous systemic treatments indicates a disease characterized by chronic course, high level of severity and some therapeutic failures (47). All these aspects can impact on the QoL of patients with AD (47).

The findings of the current study are consistent with those of published studies in relation to other dermatological diseases, such as psoriasis. Of note, available data indicate that patients with psoriasis share vulnerability to affective symptoms with subjects affected by AD, but they generally show poorer mental health than individuals with AD (48). A study reported similar rates of depression and anxiety in patients with AD and psoriasis, although the latter presented more severe psychopathology (48). These results were confirmed by a recent meta-analysis that found similar rates of suicidal ideation in subjects with AD and psoriasis, but patients with psoriasis presented more suicidal attempts than individuals with AD (49). Some authors hypothesize that patients affected by psoriasis may be more prone to mood symptoms as a result of the involvement of cell-mediated immunity, a biological mechanism shared with major depression (50, 51). Overall, all patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, particularly those involving innate or cell-mediated immunity (e.g. neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders or rheumatoid arthritis) (52), are prone to develop mood disorders. On the other hand, patients with depression and anxiety as a result of inflammatory over-reactivity, might be more likely to develop AD with respect to subjects with mental well-being. This latter aspect is more difficult to demonstrate, because, in general, AD has an earlier onset than depression; however, this hypothesis is supported by the fact that siblings of patients with neurodevelopment psychiatric disorders, such as autism (53) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (54), are more prone to develop AD.

Study limitations

The abovementioned results should be interpreted in light of the following limitations: (i) patients were previously treated with different drugs, which might have influenced some clinical features (e.g. administration of systemic corticosteroids and affective symptoms); (ii) some data were collected retrospectively (e.g. age at onset), so that they might not have always been as accurate as in controlled studies; (iii) the lack of a follow-up period due to the cross-sectional nature of the study.

Conclusion

The presence of affective symptoms, the severity of dermatological disease (especially as perceived by patients), female sex, severity of itch, poor quality of sleep and previous treatment with cyclosporine are all factors that should be taken into account when deciding to refer patients with AD to a mental health professional. Preclinical research reveals the complex relationship between severity of skin lesions and mental wellbeing: in particular, an animal study has demonstrated that treatment with the antidepressant fluoxetine ameliorates AD skin lesions by reducing psychological distress and inflammatory response (55). This finding is also supported by preliminary clinical data showing that the severity of skin lesions proportionally affects the risk of depression and anxiety (56). Of note, even though mood and anxiety symptoms are prevalent in subjects with AD, as confirmed by the current study, these patients seldom contact psychiatric clinics. The findings of the current study promote a multidisciplinary approach that is considered to be the best pathway of care for patients affected by AD (57).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the collaborators (clinicians and residents) who contributed to sample recruitment.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gulewicz KJ, Wang CQ, et al. Progressive activation of T (H)2/T (H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130: 1344–1354.

- Kowalska-Olędzka E, Czarnecka M, Baran A. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in Europe. J Drug Assess 2019; 8: 126–128.

- Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab 2015; 66: 8–16.

- Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, Girolomoni G, Puig L, Simpson EL, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy 2018; 73: 1284–1293.

- Mayba JN, Gooderham MJ. Review of atopic dermatitis and topical therapies. J Cutan Med Surg 2017; 21: 227–236.

- Margolis JS, Abuabara K, Bilker W, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ. Persistence of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol 2014; 150: 593–600.

- Cheng BT, Silverberg JI. Depression and psychological distress in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019; 123: 179–185.

- Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, Sevetson E, Block JK, Qureshi AA. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol 2017; 137: 26–30.

- Berruyer M, Delaunay J. Atopic dermatitis: a patient and dermatologist’s perspective. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021; 11: 347–353.

- Cheng CM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Bai YM, Su TP, Li CT, et al. Risk of developing major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders among adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 2015; 178: 60–65.

- Patel KR, Immaneni S, Singam V, Rastogi S, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic dermatitis, depression, and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 402–410.

- Kiebert G, Sorensen SV, Revicki D, Fagan SC, Doyle JJ, Cohen J, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with a decrement in health-related quality of life. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41: 151–158.

- Peng W, Novak N. Recent developments in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 14: 17–22.

- Honda T, Kabashima K. Reconciling innate and acquired immunity in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145: 1136–1137.

- Raison CL, Miller AH. Role of inflammation in depression: implications for phenomenology, pathophysiology and treatment. Mod Trends Pharmacopsychiatry 2013; 28: 33–48.

- Buoli M, Grassi S, Serati M, Altamura AC. Agomelatine for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2017; 18: 1373–1379.

- Troubat R, Barone P, Leman S, Desmidt T, Cressant A, Atanasova B, et al. Neuroinflammation and depression: a review. Eur J Neurosci 2021; 53: 151–171.

- Senra MS, Wollenberg A. Psychodermatological aspects of atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2014; 170: 38–43.

- Ferrucci S, Casazza G, Angileri L, Tavecchio S, Germiniasi F, Berti E, et al. Clinical response and quality of life in patients with severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a single-center real-life experience. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 791.

- Rehal B, Armstrong AW. Health outcome measures in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review of trends in disease severity and quality-of-life instruments 1985–2010. PLoS One 2011; 6: e17520.

- Charman CR, Venn AJ, Ravenscroft JC, Williams HC. Translating Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores into clinical practice by suggesting severity strata derived using anchor-based methods. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 1326–1332.

- Phan NQ, Blome C, Fritz F, Gerss J, Reich A, Ebata T, et al. Assessment of pruritus intensity: prospective study on validity and reliability of the visual analogue scale, numerical rating scale and verbal rating scale in 471 patients with chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92: 502–507.

- Gooderham MJ, Bissonnette R, Grewal P, Lansang P, Papp KA, Hong CH. Approach to the assessment and management of adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a consensus document. Section II: tools for assessing the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg 2018; 22: 10S–16S.

- Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M. The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol 2001; 10: 11–18.

- Rishi P, Rishi E, Maitray A, Agarwal A, Nair S, Gopalakrishnan S. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale assessment of 100 patients before and after using low vision care: a prospective study in a tertiary eye-care setting. Indian J Ophthalmol 2017; 65: 1203–1208.

- Martin S, Chandran A, Zografos L, Zlateva G. Evaluation of the impact of fibromyalgia on patients’ sleep and the content validity of two sleep scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009; 7: 64.

- Birdi G, Cooke R, Knibb RC. Impact of atopic dermatitis on quality of life in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol 2020; 59: e75–e91.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016; 387: 1109–1122.

- Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 2861.

- Remes O, Brayne C, van der Linde R, Lafortune L. A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations. Brain Behav 2016; 6: e00497.

- Ingegnoli F, Schioppo T, Ubiali T, Bollati V, Ostuzzi S, Buoli M, Caporali R. Relevant non-pharmacologic topics for clinical research in rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases: the patient perspective. Int J Rheum Dis 2020; 23: 1305–1310.

- Březinová E, Nečas M, Vašků V. Quality of life and psychological disturbances in adults with atopic dermatitis in the Czech Republic. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2017; 31: 227–233.

- Kwak Y, Kim Y. Health-related quality of life and mental health of adults with atopic dermatitis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2017; 31: 516–521.

- Guo F, Yu Q, Liu Z, Zhang C, Li P, Xu Y, et al. Evaluation of life quality, anxiety, and depression in patients with skin diseases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99: e22983.

- Wittkowski A, Richards HL, Griffiths CE, Main CJ. The impact of psychological and clinical factors on quality of life in individuals with atopic dermatitis. J Psychosom Res 2004; 57: 195–200.

- Falissard B, Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Papp KA, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Qualitative assessment of adult patients’ perception of atopic dermatitis using natural language processing analysis in a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2020; 10: 297–305.

- Bredewold R, Veenema AH. Sex differences in the regulation of social and anxiety-related behaviors: insights from vasopressin and oxytocin brain systems. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2018; 49: 132–140.

- Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Kouskoukis C, Christodoulou C. Psychological parameters of psoriasis. Psychiatriki 2017; 28: 54–59.

- Ando S, Nishida A, Usami S, Koike S, Yamasaki S, Kanata S, et al. Help-seeking intention for depression in early adolescents: associated factors and sex differences. J Affect Disord 2018; 238: 359–365.

- Yin H, Wardenaar KJ, Xu G, Tian H, Schoevers RA. Help-seeking behaviors among Chinese people with mental disorders: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2019; 19: 373.

- Li JC, Fishbein A, Singam V, Patel KR, Zee PC, Attarian H, et al. Sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study. Dermatitis 2018; 29: 270–277.

- Silverberg JI, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Margolis D, Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Grayson M, et al. Sleep disturbances in atopic dermatitis in US adults. Dermatitis 2021 Mar 5. [Epub ahead of print].

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, Boyle J, Fonacier L, Gelfand JM, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139: 583–590.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4: 1.

- Artz MA, Boots JM, Ligtenberg G, Roodnat JI, Christiaans MH, Vos PF, et al. Conversion from cyclosporine to tacrolimus improves quality-of-life indices, renal graft function and cardiovascular risk profile. Am J Transplant 2004; 4: 937–945.

- Flytström I, Stenberg B, Svensson A, Bergbrant IM. Methotrexate vs. ciclosporin in psoriasis: effectiveness, quality of life and safety. A randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 2008; 158: 116–121.

- Vilsbøll AW, Anderson P, Piercy J, Milligan G, Kragh N. Extent and impact of inadequate disease control in us adults with a history of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis following introduction of new treatments. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021; 11: 475–486.

- Leibovici V, Canetti L, Yahalomi S, Cooper-Kazaz R, Bonne O, Ingber A, et al. Well being, psychopathology and coping strategies in psoriasis compared with atopic dermatitis: a controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 897–903.

- Pompili M, Bonanni L, Gualtieri F, Trovini G, Persechino S, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal risks with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2021; 141: 110347.

- Guenzani D, Buoli M, Caldiroli L, Carnevali GS, Serati M, Vezza C, et al. Malnutrition and inflammation are associated with severity of depressive and cognitive symptoms of old patients affected by chronic kidney disease. J Psychosom Res 2019; 124: 109783.

- Torales J, Echeverría C, Barrios I, García O, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, et al. Psychodermatological mechanisms of psoriasis. Dermatol Ther 2020; 33: e13827.

- Ingegnoli F, Schioppo T, Ubiali T, Ostuzzi S, Bollati V, Buoli M, et al. Patient perception of depressive symptoms in rheumatic diseases: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Rheumatol 2020 Sep 10. [Epub ahead of print].

- Dai YX, Tai YH, Chang YT, Chen TJ, Chen MH. Increased risk of atopic diseases in the siblings of patients with autism spectrum disorder: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Autism Dev Disord 2019; 49: 4626–4633.

- Chang TH, Tai YH, Dai YX, Chang YT, Chen TJ, Chen MH. Risk of atopic diseases among siblings of patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2019; 180: 37–43.

- Li Y, Chen L, Du Y, Huang D, Han H, Dong Z. Fluoxetine Ameliorates atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in BALB/c mice through reducing psychological stress and inflammatory response. Front Pharmacol 2016; 7: 318.

- Schonmann Y, Mansfield KE, Hayes JF, Abuabara K, Roberts A, Smeeth L, et al. Atopic eczema in adulthood and risk of depression and anxiety: a population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 248–257.e16.

- Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. Adult-onset atopic dermatitis: characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2019; 20: 771–779.