REVIEW ARTICLE

Psychopathology Associated with Chronic Pruritus: A Systematic Review

Bárbara R. FERREIRA1,2 and Laurent MISERY1,3

1University of Brest, Laboratoire interactions épithéliums-neurones (LIEN), Brest, France, 2Department of Dermatology, Centre Hospitalier de Mouscron, Hainaut, Belgium and 3Department of Dermatology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Brest, France

There are no previous studies of the psychopathology associated with different aetiologies of chronic pruritus. A systematic review was performed of cohort and case-control studies comparing healthy controls with patients with chronic pruritus related to primary dermatoses, systemic diseases, psychogenic pruritus, idiopathic pruritus, prurigo nodularis and/or lichen simplex chronicus. The review was registered in PROSPERO and performed according to the PRISMA statement, which allowed the inclusion of 26 studies. The quality of eligible studies was assessed using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Most of the studies concern primary dermatoses and systemic diseases. Sleep disorders are a common comorbidity interrelated with pruritus, anxiety and depressive symptoms, in primary dermatoses. Sleep disorders are linked with pruritus and depressive symptoms in end-stage renal disease and hepatobiliary disease. Depressive and anxiety symptoms are associated with psychogenic pruritus. Psychogenic pruritus, lichen simplex chronicus and some primary dermatoses are linked with personality characteristics. Further studies are required to explore in depth the psychopathology linked with psychogenic pruritus and prurigo nodularis, as well as psychopathology linked with other primary dermatoses and systemic disorders associated with chronic pruritus, and to better differentiate psychogenic pruritus from psychopathological characteristics linked with other aetiologies of chronic pruritus, in order to improve the management of patients with chronic pruritus.

SIGNIFICANCE

Chronic itch is associated with mental health disorders, with huge impact on quality of life. However, no previous studies address the similarities and differences in mental health problems related to different conditions characterized by chronic itch. A systematic review was conducted on this topic. Cohort and case-control studies involving patients with skin and systemic conditions associated with chronic itch compared with healthy controls were included. Mental health disorders were mostly described in skin and systemic diseases, while studies are needed on lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis and psychogenic pruritus, in order to better characterize associated mental health problems.

Key words: pruritus; mental disorders; mental health; stress, psychological; skin diseases.

Citation: Acta Derm Venereol 2023; 103: adv8488. DOI https://doi.org/10.2340/actadv.v103.8488.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Society for Publication of Acta Dermato-Venereologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Jun 20, 2023; Published: Aug 22, 2023

Corr: Barbara R. Ferreira, University Brest, Lien, Brest, France; Department of Dermatology, Centre Hospitalier de Mouscron, Hainaut, Belgium. E-mail: barbara.roqueferreira@gmail.com

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

INTRODUCTION

The close link between chronic pruritus (CP) and psychopathology has been highlighted in primary dermatoses and systemic diseases (1, 2). In addition, pruritus is a hallmark of prurigo nodularis (PN) and lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). PN may be observed in the setting of systemic diseases causing pruritus, but also, as for LSC, associated with primary dermatoses and/or psychological aspects, the latter being less clearly understood (3, 4). Moreover, psychogenic pruritus (Psych-P) is characterized by the presence of CP, which does not result from a primary dermatosis or a systemic disease, but which is linked with psychopathology and/or a psychosocial dynamic (1, 5) and is often mistaken for idiopathic pruritus (IP). Globally, there is a lack of understanding of the similarities and differences regarding psychopathology among the disorders in which CP is a core symptom.

In a study by Dalgard et al. (6), in patients with itchy skin diseases, health-related quality of life (QoL) was more impaired than in dermatological patients without itch. Considering the link between mental health, QoL and pruritus (6), a systematic review, focussing specifically on CP, would summarize and compare psychopathological characteristics related to several aetiologies of CP and enable the establishment of future research priorities in psychodermatology.

A systematic review was performed to compile and discuss cohort and case-control studies that compare psychopathology and related QoL impact in healthy controls (HC) with patients who have a primary dermatosis associated with CP, a systemic disease responsible for CP, Psych-P, IP or a disorder placed in the interface of these main groups, namely, PN and LSC. Pruritus observed in the setting of a main psychiatric disorder, such as a delusional disorder, and skin disorders linked with psychopathology where pruritus is a secondary symptom, namely skin picking, were outside of the scope of this systematic review.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (registration number CRD42021251177) (7).

Search strategy and selection criteria

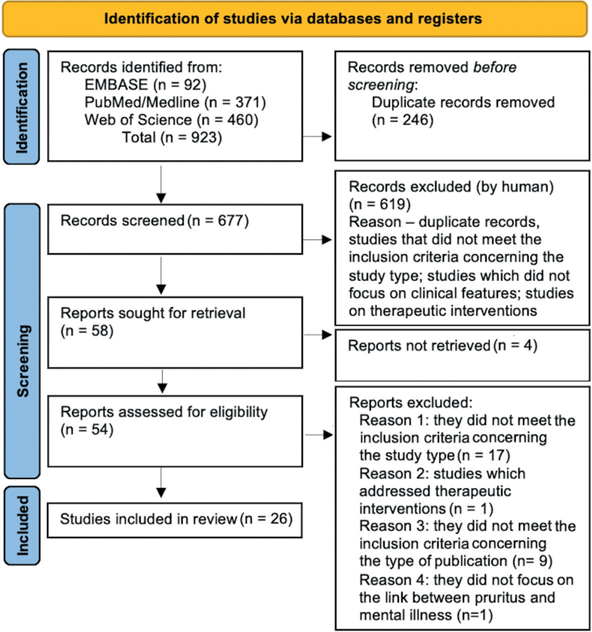

A systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (8). The databases used were: Embase, PubMed/Medline and Web of Science (Table SI). The following inclusion criteria were defined: studies published in English, French, Portuguese and Spanish; from 2001 to 2021; only with humans, without age restriction; cohort and case-control studies; peer-reviewed journal articles. The timeline was established considering the relevance of previously published papers. In Embase, the following terms were used: mental disease; mental stress; mental health; dissociative disorder; alexithymia. In PubMed/Medline, the literature search was performed using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), including the following terms: pruritus; mental disorders; stress, psychological; psychopathology; mental health; dissociative disorders; affective symptoms. The term “affective symptoms” was included to include the entry term “alexithymia”. In Web of Science, the following terms were used: pruritus; mental disorders; mental diseases; psychopathology; stress, psychological; mental health; dissociative disorders; affective symptoms; alexithymia; mental stress. In PubMed/Medline, the filters also included: studies in humans; the language, as specified above. In Embase and Web of Science, these criteria were further applied during the article selection by the 2 reviewers (BRF and LM). All article titles or abstracts were independently screened (2 reviewers); in case of doubt, they were included for further analysis. The duplicates were eliminated. All the discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The full-text articles were reviewed independently and selected studies were considered for a qualitative analysis. An algorithm for inclusion and exclusion criteria was used (PICO-principle) (9): population – patients with CP; intervention – to describe psychopathology and related QoL impairment; comparator – HC; outcome – the primary outcome was to describe psychopathology and QoL associated with CP and the secondary outcome was to describe similarities and differences related to psychopathology among 5 subgroups of patients, if sufficient data were available (Psych-P, IP, pruritus linked with primary dermatoses, pruritus associated with a systemic disease and PN/LSC). Fig. 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram obtained from this search.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram with the number of articles selected.

Data extraction

The titles and abstracts were analysed; the selected articles were organized as follows: type of study; type of pruritus, in main categories – primary dermatoses, systemic diseases, Psych-P, IP, PN and/or LSC; mental health and QoL measurement scales; first author, year of publication, country, number of patients and controls.

Quality assessment

The quality of eligible studies was assessed using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (10) and the scores were transformed into Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) standards (“good”, “fair” and “poor” quality) (Tables SII and SIII). In the cohort studies, the overall quality of the studies was good. In contrast, the quality of case-control studies was distributed as follows: 45.8% good (11/24 studies), 50% fair (12/24 studies) and 4.2% poor (1/24 studies).

RESULTS

Study selection

A total of 923 records were identified. After removal of duplicates, 677 studies remained for an initial screening based on the title and abstract, which resulted in exclusion (by human) of 619 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria (identification of a remaining duplicate, other study types than cohort and case-control studies, studies that did not include HC, studies focused only on basic science, studies addressing therapeutic interventions, and studies that did not focus on pruritus related to a systemic disease, a primary dermatosis, Psych-P, IP, PN and/or LSC). Thus, 58 reports were sought for retrieval and 54 assessed for eligibility. The full articles were then read to confirm eligibility, and 17 studies were excluded as the study design did not correspond to what had been stablished in the inclusion criteria, 1 study was eliminated because it addressed therapeutic interventions, 9 other studies were excluded because of the type of publication, and 1 study did not focus on the link between pruritus and psychopathology. A final total of 26 studies were included in the review (Fig. 1): 2 cohort and 24 case-control studies.

Study characteristics

Main topics. Details of the studies included in this systematic review are shown in Tables I and II. Table I organizes the studies according to the author, year of publication, the country where the study was conducted, the outcome measured, the disorder addressed, the number of cases and controls and the adjustment analysis when performed. Table II summarizes the key findings from each study included in this systematic review. To facilitate the data analysis and description of the main results, the studies were organized in Table I, taking into account the main group of skin disorders, where the disorder addressed could be included: studies addressing psychopathology and related QoL impairment linked with pruritus associated with primary dermatoses (16 studies); studies addressing psychopathology and related QoL impairment linked with pruritus associated with systemic diseases (6 studies); studies addressing psychopathology linked with LSC (3 studies); studies addressing psychopathology and related QoL impairment linked with Psych-P (1 study). The definition used in this review to consider the diagnosis “Psych-P” was that mentioned in the International Classification of the Diseases 11th revision (ICD-11) (11). No studies regarding PN were retrieved. Studies on LSC were placed in a separate group. Most of the studies on psychopathology associated with CP have been performed with patients with primary dermatoses, followed by pruritus associated with systemic disorders. No studies were obtained specifically covering IP.

| First author, year (reference) | Country | Outcome measured | Type of study; N cases/controls | Statistical analysis adjusted for |

| Primary dermatoses | ||||

| Alanne S, 2011 (12) | Finland | QoL (IDQOL index form), in infants with AD; effects of AD on physical and emotional health (including pruritus, mood, SD). | Prospective cohort 6 M: 20 AD/106 HC 12 M: 2 AD/105 HC 24 M: 13 AD/86 HC |

N.A. |

| Bender BG, 2003 (13) | USA | Sleep quality in adults with moderate to severe AD (assessment with PSQI, DLQI, IRS and an actigraph). | Prospective case-control 14 AD/14 no dermatoses |

N.A. |

| Conrad R, 2008 (22) | Germany | Pruritus in CIU and PSO adult patients and negative emotions (assessment with TAS-20, SCL-90-R, STAXI). | Prospective case-control 41 CIU + 44 PSO/49 HC |

MLR: age, sex, skin status, duration of illness, TAS-20, SCL-90-R, STAXI |

| Holm EA, 2006 (14) | Denmark | AD and HRQoL (assessment with DLQI, CDLQI, SF-36, SCORAD, VASs for eczema severity (PTVAS) and pruritus (PRUVAS)). | Prospective case-control 101 AD/30 HC |

MLR: age, sex, pruritus, patient severity assessment. |

| Horev A, 2017 (15) | Israel | AD and ADHD in children. | Retrospective case-control 840 AD(CHS)/900 GP |

MLR: age, BMI, SES |

| Jensen P, 2018 (25) | Denmark | Sleep (ISI, PSQI), plaque PSO (PASI), pruritus (ISS), depression (BDI), stress (PSS), HRQoL (DLQI) in adult patients. | Prospective case-control 179 PSO/105 HC |

MLR: age, sex, marital status, BMI, psoriasis duration, PASI, psoriatic arthritis, systemic treatment, DLQI, ISS, BDI, PSS |

| Kaaz K, 2018 (24) | Poland | Pruritus, pain severity (VAS), sleep (AIS; PSQI), QoL (DLQI) and HS (HSS; Hurley staging) in adolescents and adults. | Prospective case-control 108 HS/50 HC |

N.A. |

| Kaaz K, 2019 (16) | Poland | Severity of pruritus and pain (VAS), sleep quality (AIS; PSQI), QoL (DLQI), severity of AD (SCORAD) and plaque PSO (PASI) in adults. | Prospective case-control 100 AD + 100 PSO/50 HC |

N.A. |

| Kalinska-Bienias A, 2019 (21) | Poland | Intensity of pruritus (NWMs, VAS), sleep quality (actigraphy) and severity of BP (BPDAI) in adult patients. | Prospective case-control 31 BP/40nonpruritic HC |

N.A. |

| Liu JM, 2017 (27) | Taiwan | Children with scabies and PDC (DSM-5 and data from the NHIRD). | Prospective cohort 2137 scabies/8548 without scabies |

CPR: sex, age, income, geography, urbanization, comorbidities |

| Mochizuki H, 2019 (17) | USA | Acute stress (TSST), experimentally induced cowhage itch, scratching and AD severity (EASI) in adults with AD. | Prospective case-control 15 AD/16 HC |

N.A. |

| Ograczyk-Piotrowska A, 2018 (23) | Poland | Stress intensity, last month (VAS, SRRS), CiU severity (UAS), pruritus (ISEQ) and QoL (CU-Q2oL) in female adult patients. | Prospective case-control 46 CU/33 HC |

N.A. |

| Oh SH, 2010 (18) | Korea | Stress (BDI, STAI, IAS and PBC-BCC), QOL (DLQI) and AD (EASI) in adolescent and adult patients. | Prospective case-control 28 AD/28 HC |

N.A. |

| Shut C, 2014 (19) | Germany | Personality, depression or anxiety (NEO-FFI, HADS and SCS), intensity of mental itch induction (VAS) and AD. | Prospective case-control 27 AD/28 HC |

LR: personality characteristics (NEO-FFI), depression and anxiety (HADS), SCS |

| Shutty BG, 2013 (26) | USA | Sleep quality, depression, itch and plaque PSO with at least 10% BSA (PSQI, ESS, ISI, PHQ-9, ISS) in adult patients. | Prospective case-control 35 PSO/44 HC |

MLR: sex, BMI, age, PHQ-9 |

| Tran BW, 2010 (20) | USA Singapore |

Itch, scratching, ANS and moderate to severe AD adult patients (HRV, sweating, TEWL, skin moisture, after histamine-induced itch, scratching around the itch site and TSST). | Prospective case-control 21 AD/24 HC |

N.A. |

| Systemic diseases | ||||

| Benito de Valle M, 2012 (30) | England Sweden | HRQoL (SF-36), anxiety, depression (HADS), fatigue (FIS) and adult patients with PSC (CLDQ). | Prospective case-control 218 from Sweden + 60 from England (182 completed the questionnaires)/controls – GP (364 for the SF-36, 858 for the FIS, normal values for HADS) |

LR: SF-36, CLDQ |

| Cheung AC, 2016 (31) | Canada | Liver disease, IBD, HRQoL (LDQOL, PBC-40, SF-36, SIBDQ) and depression (PHQ-9) in adult patients. | Prospective case-control 162 PSC with or without IBD, PBC, NACLD and isolated IBD and Canadian normative data (HC) |

LR: sex, age at diagnosis of liver disease and the presence of PSC |

| Montagnese S, 2013 (32) | Italy | Sleep (ESS, KSS, STSQ), fatigue (D-FIS), itch (VAS), HRQoL (SF-36), in adult patients with PBC. | Prospective case-control 74 PBC/60 cirrhosis and 79 HC |

LR: age, fatigue, sleep timing/quality |

| Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, 2016 (33) | Poland | HRQoL in adult PBC patients (PBC-40, PBC-27, SF-36). | Prospective case-control 205 PBC/85 HC |

N.A. |

| Schricker S, 2011 (28) | Germany | Inflammatory clinical data, pruritus (VAS), mental data (ADS-L, TAS-20) and QoL (SF-36) in HD adult patients. | Retrospective case-control 19 HD with pruritus/20 HD without pruritus and 15 HC |

N.A. |

| Yngman-Uhlin P, 2011 (29) | Sweden | Sleep (actigraphy, sleep diary, USI), fatigue and HRQoL (FACIT, SF-36) in adult patients doing PD. | 28 PD/22 CAD and 18 participants from the GP | N.A. |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | ||||

| Altunay IK, 2021 (34) | Turkey | The levels of stress (PSS), depression, anxiety (HADS), QoL (DLQI) in adult patients with LSC, and the severity of the disease and pruritus. | Prospective case-control 36 LSC/36 HC |

LR: sex, age, DLQI, HADS, VAS, PSS |

| Martín-Brufau R, 2010 (35) | Spain | Personality variables (MIPS) in adults with LSC. | Prospective case-control 60 LSC/1184 HC |

N.A. |

| Martín-Brufau R, 2017 (36) | Spain | Sex differences in personality styles (MIPS), among adolescent and adult patients with LSC. | Prospective case-control 103 LSC/1184 HC |

N.A. |

| Psychogenic pruritus | ||||

| Yilmaz B, 2016 (37) | Turkey | Type D personality, anxiety, depression and personality traits in patients with isolated itching of the external auditory canal (Type D Scale; EPQR-A; HADS; Modified ISS). | Prospective case-control 100 isolated itching of the external auditory canal/100 HC |

LR: age, sex, Type D Scale, HADS, EPQR-A, Modified ISS |

| AD: atopic dermatitis; ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADS-L: Allgemeine Depressionsskala: Langform; AIS: Athens Insomnia Scale; ANS: autonomic nervous system; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BMI: body mass index; BP: bullous pemphigoid; BPDAI: Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index; BSA: body surface area; CAD: coronary artery disease; CDLQI: Children’s DLQI; CHS: Clalit Health Services; CIU: chronic idiopathic urticaria; CiU: chronic inducible urticaria; CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; CPR: Cox proportional hazards regression models; CU: chronic urticaria; CU-Q2oL: Chronic urticaria-quality of life; D-FIS: Daily Fatigue Impact Scale; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; EPQR-A: Abbreviated version of the revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; FACIT: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy; FIS: Fatigue Impact Scale; GP: general population; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HC: healthy controls; HD: haemodialysis; HRQoL: health-related quality of life; HRV: heart rate variability; HS: hidradenitis suppurativa; HSS: Hidradenitis Suppurativa Score; IAS: Interaction Anxiousness Scale; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IDQOL: Infant Dermatitis Quality of life; ISEQ: Itch Severity Evaluation Questionnaire; IRS: Itching Rating Scale; ISI - Insomnia Severity Index; ISS: Itch Severity Scale; KSS: The Karolinska Sleepiness Scale; LDQOL: Liver Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire; LR: linear regression; LSC: lichen simplex chronicus; M: months; MIPS: Millon Index Personality Styles; MLR: multivariate logistic regression; N.A.: not applicable; NACLD: non-autoimmune cholestatic liver disease; NEO-FFI: Neo Five-Factor Inventory; NHIRD: National Health Insurance Research Database; NWMs: nocturnal wrist movements; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PBC: Primary biliary cirrhosis; PBC-BCC: Private Body Consciousness subscale of the Body Consciousness Questionnaire; PBC-27: Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-27; PBC-40: Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-40; PD: peritoneal dialysis; PDC: psychiatric disorders in childhood; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PRUVAS: VAS for pruritus; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis; PSO: psoriasis; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; PTVAS: VAS for eczema severity; QoL: quality of life; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist 90-R; SCORAD: Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis; SCS: Self-Consciousness Scale; SD: sleep disorders; SES: socio-economic status; SF-36: Short-Form 36; SIBDQ: Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; SRRS: Social Readjustment Rating Scale; STAI - State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; STAXI: State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory; STSQ: Sleep Timing and Sleep Quality Screening Questionnaire; TAS-20: Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale; TEWL: trans-epidermal water loss; TSST: Trier Social Stress Test; UAS: Urticaria Activity Score; USI: Uppsala Sleep Inventory; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale. | ||||

| First author, year (reference) | Key findings |

| Primary dermatoses | |

| Alanne S, 2011 (12) | Pruritus and SD had significant impact on QoL in AD. QoL of children with mild to moderate AD was poorer at 6 and 12 months than what is observed in healthy infants, mostly because of pruritus and scratching as well as sleep problems. |

| Bender BG, 2003 (13) | The AD group reported lower sleep quality, more awakening and daytime dysfunction with increased pruritus and lower QoL compared with controls. |

| Conrad R, 2008 (22) | CIU and PSO patients had higher scores in TAS-20, emotional distress, depression, anxiety, state anger, anger-in and anger-out compared with HC. For pruritus severity, in CIU patients, the state anger was the only significant predictor and, in PSO, the only significant predictor was depression. |

| Holm EA, 2006 (14) | Scores of DLQI, CDLQI and pruritus were related to SCORAD. All dimensions of SF-36 were more correlated with DLQI than with PTVAS. CDLQI had the highest correlation with PCS; PTVAS and DLQI were more correlated with MCS. In MCS, women had lower HRQoL. |

| Horev A, 2017 (15) | The proportion of ADHD was 7.1% in patients with AD compared with 4.1% in the control group. ADHD was associated with AD among boys. Increasing age was associated with increased risk of ADHD. The higher prevalence of ADHD could be related to pruritus and SD. |

| Jensen P, 2018 (25) | In PSO, sleep quality is poorer than HC. Scores for pruritus, stress, DLQI and depression were higher in poor sleepers compared with normal sleepers. PASI scores were only associated with longer sleep onset latency. Higher scores on the ISS predicted poorer sleep quality. |

| Kaaz K, 2018 (24) | In HS, sleep quality was severely more affected compared with HC. Pain was a crucial factor responsible for poor sleep quality, with no pruritus related impact on PSQI scores. The severity of pruritus and pain was correlated with AIS scores. AIS and PSQI scores correlated with DLQI. |

| Kaaz K, 2019 (16) | SD were more common in AD (AIS and PSQI) and in PSO than in the controls (PSQI). In AD and PSO, the severity of pruritus correlated with the AIS scores. PSO patients had a shorter sleep and AD patients more trouble sleeping. |

| Kalinska-Bienias A, 2019 (21) | Scratching, defined as bouts of NWMs, was significantly more important in BP than in controls. Total sleep duration was shorter for patients with BP than for controls. A negative correlation was observed between VAS (pruritus severity) and total sleep duration. |

| Liu JM, 2017 (27) | 607 (5.68%) children developed a psychiatric disorder in the subsequent 7-year follow-up period. The overall incidence of PDC was similar in the scabies group and the control group, but patients with scabies had a higher risk of developing ID. |

| Mochizuki H, 2019 (17) | The TSST-induced stress was significantly and positively correlated with the EASI score in the patients with AD. Following acute stress, patients with AD reported a reduction of itch sensation and need to scratch and an increase in spontaneous off-site scratching. |

| Ograczyk-Piotrowska A, 2018 (23) | CiU patients experienced more intensive stress regarding subjective perception (VAS). A higher activity of the disease was associated with a higher stress level (VAS and SRRS) and worse QoL. Any significant correlations between stress and pruritus were observed (VAS and SRRS). |

| Oh SH, 2010 (18) | Patients with AD showed high scores on all of the questionnaires (BDI, STAI, IAS, PBC and DLQI). Statistically significant positive correlations were observed between each psychological parameter and DLQI. Pruritus was positively correlated with anxiety state and anxiety trait. |

| Shut C, 2014 (19) | Compared with controls, patients with AD were more neurotic, less extraverted, less agreeable, more depressed and reported a higher itch intensity after the presentation of the experimental video to induce itch and more scratch movements, without a link with an increase in itch intensity. |

| Shutty BG, 2013 (26) | Mean ISI and PSQI scores were higher for PSO. For PSO: 4.3 times the odds to score for insomnia (ISI), 6.1 times the odds to be depressed (PHQ-9), no more likely to be “sleepy” (ESS) and a trend toward “poor sleep” (PSQI). Mean ISS was significantly higher in those with PSO. |

| Tran BW, 2010 (20) | AD patients had a higher heart rate than HC (post-histamine, post-scratching and post-stress) and a dysfunctional parasympathetic response to itch and scratching, as demonstrated by high-frequency component values (HRV parameters). In AD, there is a lower skin hydration and higher trans-epidermal water loss than controls. Patients with AD had a significant decrease from rest in palm TEWL after exposure to histamine and scratching. |

| Systemic diseases | |

| Benito de Valle M, 2012 (30) | PSC was associated with lower scores in SF-36, excepting for the physical functioning and bodily pain. Pruritus predicted SF-36 bodily pain, role functioning, SF-36 PC. Liver transplantation did not associate with different HRQoL impact, excepting for the general health SF-36 domain. Cirrhosis was associated with lower SF-36 physical functioning, role functional, general health, mental health and PC scores. CLDQ domain scores were associated with SF-36 PC and MC. Fatigue, depression or anxiety did not differ between PSC and controls. |

| Cheung AC, 2016 (31) | Patients with abnormal ALP had higher itch scores in PBC-40. Disease type had no significant influence on HRQoL – SF-36 physical and MC scores. Multivariable analysis of factors influencing HRQoL as determined by the MC score demonstrated that disease type did not have a significant impact. MC score was significantly worse for those with more severe itch in the PBC-40 and more severe depression according to the PHQ-9. |

| Montagnese S, 2013 (32) | Habitual sleep timing was delayed in PBC and cirrhosis. For cirrhosis, higher number of night awakenings compared with HC and PBC. PBC and pruritus were associated with prolonged sleep latency and earlier wake-up times; for PBC, fatigue was the only independent predictor of SF-36 MC; sleep quality was the only independent predictor of the mental health domain. |

| Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, 2016 (33) | PBC patients had higher HRQoL (SF-36) impairment than HC. In PBC-40/27, ALP levels correlated with itch. There were correlations between PBC-40/PBC-27’s Cognitive domain and SF-36’s MC as well as PBC emotional domain and mental health and role-emotional of SF-36. |

| Schricker S, 2011 (28) | Pruritus, impaired mental health and pro-inflammatory state were associated with each other and all correlated with mortality in chronic kidney disease. Higher inflammatory parameters were associated with worse impaired mental health and pruritus; worse pruritus was associated with worse impaired mental health in HD patients. |

| Yngman-Uhlin P, 2011 (29) | PD patients had more fragmented sleep and worse sleep efficiency than the CAD and the general population groups. Pruritus and fatigue were prevalent in PD patients and correlated with fragmented sleep and worse sleep efficiency. In HRQoL, the PC score was decreased in the PD and CAD groups, compared with the general population. |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | |

| Altunay IK, 2021 (34) | The scores of PSS and HADS were statistically higher in patients: patients with LSC had higher levels of perceived stress, anxiety and depression compared with controls. |

| Martín-Brufau R, 2010 (35) | High scores on the ”Dutiful/Conforming” scale; lower ”Dominant/Controlling” scores and higher ”Cooperative/Agreeing” scores; a greater tendency to be accommodating regarding life situations, to prioritize the needs of others over their own, to follow their feelings instead of reason. Negative emotional states were a main personality component. |

| Martín-Brufau R, 2017 (36) | Women with LSC were more pessimistic, oriented to fulfil the needs of others, submissive and had a higher tendency to cover their negative feelings from others, than men with the disorder and compared with healthy women. Men with LSC had a higher score in conservative scale, in dutiful/conforming scale and in other-nurturing scale; they relied more on other people than themselves. |

| Psychogenic pruritus | |

| Yilmaz B, 2016 (37) | The prevalence of individuals with a type D personality was statistically significantly higher in patients with isolated itching of the external auditory canal (43%) than in control participants (15%). The cases had higher negative affectivity, social inhibition, anxiety and depression levels. Type D personality participants had a significantly lower score on the extraversion dimension suggesting that introvert patients presented more severe pruritus compared with the non-introverts. |

| AD: atopic dermatitis; ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AIS: Athens Insomnia Scale; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BP: bullous pemphigoid; CAD: coronary artery disease; CDLQI: Children’s DLQI; CIU: chronic idiopathic urticaria; CiU: chronic inducible urticaria; CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; EPQR-A: Abbreviated version of the revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; FID: Functional itch disorder; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HC: healthy controls; HD: haemodialysis; HRQoL: health-related quality of life; HRV: heart rate variability; HS: hidradenitis suppurativa; IAS: Interaction Anxiousness Scale; ID: intellectual disability; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; ISS: Itch Severity Scale; LSC: lichen simplex chronicus; MC: Mental Component; MCS: Mental Component Score; NWMs: nocturnal wrist movements; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis; PBC-BCC: Private Body Consciousness subscale of the Body Consciousness Questionnaire; PBC-27: Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-27; PBC-40: Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-40; PC: Physical Component; PCS: Physical Component Score; PD: peritoneal dialysis; PDC: psychiatric disorders in childhood; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis; PSO: psoriasis; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; PTVAS: VAS for eczema severity; QoL: quality of life; SCORAD: Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis; SD: sleep disorders; SF-36: Short-Form 36; SRRS: Social Readjustment Rating Scale; STAI - State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; TAS-20: Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale; TEWL: trans-epidermal water loss; TSST: Trier Social Stress Test; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale. | |

Number of studies according to the main topics. In the group “primary dermatoses”, 9 studies (12–20) focused on atopic dermatitis (AD), 1 study (21) on bullous pemphigoid (BP), 2 studies (22, 23) on chronic urticaria (CU), 1 study (24) on hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), 4 studies (16, 22, 25, 26) on psoriasis, and 1 study (27) on scabies. The group “systemic diseases” includes 2 studies (28, 29) on end-stage renal disease (ESRD), including 1 study (28) with patients on haemodialysis (HD) and 1 study (29) with patients on peritoneal dialysis (PD), 4 studies (30–33) on hepatobiliary disease (HBD), from which 1 study (30) addressed primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), 1 study (31) on both PSC and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), and 2 studies (32, 33) addressed PBC. The group “lichen simplex chronicus” includes 3 studies (34–36). The group “psychogenic pruritus” includes a study (37) comparing a localized form of Psych-P (isolated itching of the external auditory canal) with HC.

Primary dermatoses

Atopic dermatitis. In a study by Mochizuk et al. (17), psychological stress induced by the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), in adult patients with AD, was significantly and positively correlated with the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score. The authors observed that, following acute stress, the patients showed a significant increase in scratching. The effects of stress on the severity of AD were also studied by Tran et al. (20), who observed that adult patients with moderate to severe AD presented a more dysfunctional parasympathetic response to itch and scratching than the controls.

Some personality characteristics have been associated with AD. In a study by Schut et al. (19), these patients were more neurotic and depressed and less extraverted and agreeable than controls. They reported a higher itch intensity than controls after the presentation of an experimental video to induce pruritus and showed significantly more scratch movements. Depression was a significant predictor of induced itch. The authors also observed that patients who scored high on public self-consciousness and low on agreeableness showed a higher increase in the number of scratch movements than patients with the opposite scores. In controls, the increase in self-rated itch intensity could not be predicted by personality characteristics or depression. Oh et al. (18), in a study of adolescent and adult patients with AD, showed that they presented high scores of state and trait anxiety in the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Index. Pruritus was positively correlated with anxiety state and anxiety trait. The patients also presented a higher prevalence of a mood disorder, namely, depression, assessed through the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

Sleep disorders (SD) are prevalent and have huge impact on QoL. These disorders have been described both in childhood (12) and adult patients. Bender et al. (13), in a study with adults with AD, found that, in the actigraphy sleep measurement, AD patients slept less and awoke more often, having a lower sleep efficiency than the controls, and that this was associated with increased pruritus and higher impact on QoL. In turn, in a study by Kaaz et al. (16), 80% of adult patients with AD, but only 22% of controls were classified as poor sleepers (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) ≥ 5) and the severity of pruritus was significantly correlated with the scores obtained in the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS).

In a study by Holm et al. (15), with paediatric and adult patients with AD, patients’ mental health and social functioning seemed to be more affected than physical functioning (36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36)). Strongest correlations were found between Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and the mental dimensions of SF-36, including the mental component score (16). In another study, with paediatric AD patients, the proportion of cases with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was 7.1%, significantly higher than in controls and the risk was higher in boys and with increasing age.

Bullous pemphigoid and other blistering disorders. SD are associated with pruritus in blistering disorders, such as BP. In a study by Kalinska-Bienias et al. (21), actigraphy-measured sleep analysis showed that patients with BP presented significantly lower sleep efficiency with shorter total sleep duration than controls. A negative correlation was observed between a visual analogue scale (VAS) to measure the severity of pruritus and total sleep duration. SD were also associated with the severity of the dermatosis.

Chronic urticaria. Conrad et al. (22) observed that depression and anxiety were prevalent in CU, in a study involving adult patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU). Moreover, they showed that, after controlling for depression, patients with CIU had higher scores in the Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) than the controls and the score was correlated with emotional distress measured by the sum score (Global Severity Index) generated through the Symptom Checklist 90-R (SCL-90-R). In addition, the authors observed that patients with CIU had higher prevalence of state anger, anger-in (the tendency to keep one’s own anger in) and anger-out (the tendency to openly express the anger), assessed through the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI), compared with HC. The authors also observed that the state anger was the only significant predictor for pruritus severity.

In a study by Ograczyk-Piotrowska et al. (23), involving adult female patients diagnosed with chronic inducible urticaria, a higher activity of the disease was significantly associated with a higher stress level (VAS and Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS)) and worse QoL; the strongest correlations were observed between disease severity and subscales itching and functioning.

Hidradenitis suppurativa. Kaaz et al. (24) found that, in a group of adolescent and adult patients with HS, SD were more prevalent than in HC, including sleep latency, sleep duration and habitual sleep efficiency. Pain significantly affected subjective sleep quality, sleep duration and daytime dysfunction. The severity of pruritus and pain were significantly correlated with AIS scores.

Psoriasis. In a study by Conrad et al. (22), with adult psoriasis patients, they presented higher prevalence of alexithymia, with higher scores in TAS-20, higher emotional distress measured by the Global Severity Index, as well as higher prevalence of depression and anxiety (SCL-90-R), state and trait anger, anger-in and anger-out (STAXI) compared with HC. Depression was the only significant predictor for the severity of pruritus.

Several studies described the high prevalence of SD and depression in psoriasis. Shutty et al. (26) observed that the mean Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score was significantly higher in adult psoriasis patients than in controls. Patients with psoriasis had 4.3 times the odds to score in a higher insomnia category in ISI and 6.1 times the odds to be depressed in Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score. When adjusting for age, body mass index, sex and depression, mean Itch Severity Scale (ISS) was significantly higher in those with psoriasis compared with controls. Jensen et al. (25) also observed that SD were prevalent in a group of adult patients with plaque psoriasis and were more common than in HC. Patients with psoriasis presented shorter total sleep time, longer sleep latency and poorer sleep efficiency. Higher scores in the ISS predicted higher levels of insomnia. Scores for pruritus, stress, DLQI and depression were significantly higher in poor sleepers compared with normal sleepers, with no difference regarding the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). More cognitive-affective depressive symptoms were associated with poorer outcomes of global sleep quality, sleep onset latency and sleep efficiency. More somatic depressive symptoms were associated with insomnia severity and poorer global sleep quality. In a study by Kaaz et al. (16), with adult patients with psoriasis, these patients reported more difficulties with final awakening than controls. The mean scores for PSQI were higher in psoriasis than in controls and 80% of patients with psoriasis were classified as poor sleepers. In addition, the severity of pruritus was significantly correlated with AIS and PSQI.

Skin infections and infestations. In a cohort study by Liu et al. (27), with 2,137 children with a diagnosis of scabies, 607 (5.68%) developed a psychiatric disorder in the subsequent 7-year follow-up period. Patients with scabies had higher risk of developing intellectual disability.

Systemic diseases

End-stage renal disease. In a case-control study by Schricker et al. (28), with patients undergoing haemodialysis (HD), pruritus, impaired mental health and chronically elevated inflammatory parameters were associated with each other and all correlated with mortality.

In a case-control study, with patients on PD, they exhibited more fragmented sleep and worse sleep efficiency than the coronary artery disease and the general population groups. Pruritus correlated with the SD (29).

Hepatobiliary diseases. Benito de Valle et al. (30) observed, in a 2 population-based cohort of patients with PSC, that these patients had lower scores in SF-36 domains compared with the general population and that pruritus was an independent predictor of the SF-36 bodily pain and role functioning domains. The severity of hepatic disease was associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as patients with cirrhosis had lower SF-36 physical functioning, role functional, general health, mental health compared with non-cirrhotic patients (30). In another study with adult patients with PSC, impairment of mental HRQoL is associated with the impact of hepatic disease on lifestyle restrictions, social interactions, pruritus and depression. The mental component score, assessed with the SF-36, was significantly worse for those with more severe pruritus assessed with the Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-40 and more severe depression according to the PHQ-9 (31).

Montagnese et al. (32) conducted a case-control study with patients with PBC and observed that SD were more common compared with HC and that those with significant pruritus had prolonged sleep latency and earlier wake-up times. Sleep quality was the only independent predictor of psychopathology. In a prospective cohort, patients with PBC had significant HRQoL impairment, assessed through the SF-36, also including the mental component, compared with HC (33).

Lichen simplex chronicus

Altunay et al. (34) reported that patients with LSC presented significantly higher levels of stress (Perceived Stress Scale-10) and a statistically significant increased risk of anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) compared with HC. The scores for depression were correlated with pruritus (VAS).

In a case-control study by Martín-Brufau et al. (35), adult patients with LSC had a greater tendency to prioritize the needs of others over their own and to follow their feelings rather than reason. Negative emotional states were observed as a main personality characteristic: the patients tend to behave in a more pessimistic way and to be more preoccupied and focused on their problems. In another study by the same authors, with adolescent and adult patients, women with LSC were more pessimistic, oriented to fulfil the needs of others and submissive, and had a higher tendency to hide their negative feelings from others than were men with the disorder and healthy women. Men with LSC were more traditional, more dutiful and oriented to fulfil the needs of others than those without the disorder (36).

Psychogenic pruritus

Yilmaz et al. (37) studied a group of patients with a localized form of Psych-P. The cases included patients with isolated itching of the external auditory canal and they presented a significantly higher prevalence of type D personality than the controls. Furthermore, these patients exhibited greater negative affectivity, social inhibition as well as increased levels of anxiety and depression than the HC.

DISCUSSION

The studies retrieved from this systematic review mostly address psychopathology in primary dermatoses and systemic diseases. However, a wide spectrum of psychopathology was described in different disorders in which CP is a main symptom (primary dermatoses, systemic diseases, LSC and Psych-P). Some similarities and differences can be discussed.

Psychopathology and disorders associated with chronic pruritus: similarities

Depressive symptoms and SD are relatively common across the disorders described herein. Depressive symptoms were reported in disorders belonging to different categories: primary dermatoses (AD, CU, psoriasis), Psych-P and systemic diseases (ESRD and HBD) (18, 22, 31).

In turn, SD have also been described in several dermatoses, namely, AD, BP, CU, HS and psoriasis (12, 13, 16, 21, 24–27). Moreover, they are also a hallmark in ESRD and HBD, such as, in PBC (32). Pruritus seems to be an important feature correlated with SD, with particular impact in primary dermatoses (AD (16), HS (24), BP (21)) and systemic diseases (HBD (32)).

SD commonly have a link with mood disorders, especially, depression, but also with anxiety and this connection may be enhanced by the presence of pruritus. This link was observed in AD, where depression seems to be a predictor of pruritus (19) and anxiety correlated with pruritus (18). Depression is also linked with psoriasis, where it correlates with pruritus [25]. In psoriasis, SD are also correlated with depression (22). In turn, in systemic diseases associated with pruritus, it was observed that, in PSC, depression has also a link with pruritus (31). Thus, in primary dermatoses, SD seem to be linked with anxiety and depression, while in ESRD and HBD only depression was associated with sleep problems.

Sleep quality is a central characteristic of mental health. However, it is difficult to always predict whether depression and SD can occur before, or as a result of the experience of having, pruritus. Nevertheless, depression and psychopathology considered globally can also occur as a consequence of QoL impairment resulting from pruritus, as it was observed, for example, in the study by Schricker et al. (28), with patients undergoing HD, and subsequently can contribute to SD. On the other hand, in children with AD, the higher prevalence of ADHD could be related to pruritus and SD, as discussed by Horev et al. (15).

Finally, regarding personality characteristics, alexithymia was reported in primary dermatoses, such as psoriasis and CU (22). Alexithymia is a personality construct related to one’s inability to deal with emotional regulation, thus leads to difficulty in identifying and describing feelings, impoverished fantasy life and externally-oriented thinking (38).

Psychopathology and disorders associated with chronic pruritus: differences

Depression and anxiety disorders may coexist in most of the primary dermatoses associated with CP and in Psych-P (17, 22, 37). In contrast, in systemic diseases linked with pruritus, anxiety is less commonly reported than depression. We speculate that, while depression could be similarly common in both disorders (chronic dermatoses and systemic disorders), at least as a consequence (secondary psychiatric comorbidity) of having a chronic condition characterized by chronic itch, anxiety would be more common in those disorders in which stress plays a role in the pathophysiology, namely, psychophysiological dermatoses (e.g. AD, CIU). Indeed, in contrast to psychophysiological dermatoses, the pathophysiology of systemic disorders associated with CP does not involve psychological stress. Thus, the mental health disorders traditionally associated with the pathological body reaction to stress, anxiety disorders, could be less common compared with depression.

Psych-P was also observed to be related to depression and anxiety (37). Furthermore, patients with Psych-P may exhibit characteristics of type-D personality (37). The construct of type-D personality was first introduced by Denollet et al. (38) to define the subject’s general tendency to psychological distress, characterized by negative affectivity and social inhibition. Negative affectivity is closely linked with depressive mood and anxiety.

Finally, in LSC, personality characteristics characterized by pessimistic personality traits were mainly reported (36). A pessimistic way of thinking thus seems to be shared with Psych-P, thus contrasting with the other disorders discussed in this systematic review.

Future research directions

Alexithymia is a characteristic that may modulate the experience of CP and the coping mechanisms to deal with it and explain why CP could be underreported in some patients. Indeed, even though CP is a well-recognized symptom with interrelated psychopathology in some dermatoses, such as AD, it is underreported in others, namely HS (18–20, 22, 24). The evidence supports the connection between alexithymia and poor physical and mental health (38). Further studies are required into the impact of addressing alexithymia and the experience of CP as well as into the impact of treatments for CP on alexithymia.

Psych-P is a type of CP linked with psychiatric and psychosocial characteristics that should be better differentiated from other group categories of CP (1, 39). In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), Psych-P is placed in the group “Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders”, along with other conditions with somatic symptoms that may also have psychiatric comorbidities, but whose pruritus is associated with another medical condition leading to secondary psychopathology (40). This classification may then overpsychologize the latter group of patients. In turn, the ICD-11 recognizes Psych-P as a new subtype of CP, where there is no organic aetiology, but only a link with stress and/or depression is mentioned (11). Studies are needed to broaden our knowledge of Psych-P, namely, psychopathology and psychosocial features linked with it (1).

Further studies are also required to better characterize the link between psychopathology and PN as well as between psychopathology and other chronic dermatoses and systemic diseases associated with CP, to raise awareness of Psych-P and its difference from psychopathology related to CP, globally considered, in order to improve the management of CP (39).

REFERENCES

- Schneider G, Grebe A, Bruland P, Heuft G, Ständer S. Criteria suggestive of psychological components of itch and somatoform itch: study of a large sample of patients with chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00075.

- Golpanian RS, Lipman Z, Fourzali K, Fowler E, Nattkemper LA, Chan YH, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in non-psychogenic chronic itch, a US-based study. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00169.

- Ständer HF, Elmariah S, Zeidler C, Spellman M, Ständer S. Diagnostic and treatment algorithm for chronic nodular prurigo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: 460–468.

- Lotti T, Buggiani G, Prignano F. Prurigo nodularis and lichen simplex chronicus. Dermatol Ther 2008; 21: 42–46.

- Stumpf A, Schneider G, Ständer S. Psychosomatic and psychiatric disorders and psychologic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol 2018; 36: 704–708.

- Dalgard FJ, Svensson Å, Halvorsen JA, Gieler U, Schut C, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. Itch and mental health in dermatological patients across Europe: a cross-sectional study in 13 countries. J Invest Dermatol 2020; 140: 568–573.

- Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher DD, Petticrew M, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2012; 1: 2.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71.

- Da Costa Santos CM, de Mattos Pimenta CA, Nobre MR. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Lat Am Enferm 2007; 15: 508–511.

- Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Robertson J, Peterson J, Welch V, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2013. [accessed 2022 Nov 2]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). 2018. [accessed 2022 Nov 2] Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1040617588.

- Alanne S, Nermes M, Söderlund R, Laitinen K. Quality of life in infants with atopic dermatitis and healthy infants: a follow-up from birth to 24 months. Acta Paediatr 2011; 100: e65–70.

- Bender BG, Leung SB, Leung DY. Actigraphy assessment of sleep disturbance in patients with atopic dermatitis: an objective life quality measure. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111: 598–602.

- Holm EA, Wulf HC, Stegmann H, Jemec GB. Life quality assessment among patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154: 719–725.

- Horev A, Freud T, Manor I, Cohen AD, Zvulunov A. Risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2017; 25: 210–214.

- Kaaz K, Szepietowski JC, Matusiak Ł. Influence of itch and pain on sleep quality in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol 2019; 99: 175–180.

- Mochizuki H, Lavery MJ, Nattkemper LA, Albornoz C, Valdes Rodriguez R, Stull C, et al. Impact of acute stress on itch sensation and scratching behaviour in patients with atopic dermatitis and healthy controls. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 821–827.

- Oh SH, Bae BG, Park CO, Noh JY, Park IH, Wu WH, et al. Association of stress with symptoms of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 2010; 90: 582–588.

- Schut C, Bosbach S, Gieler U, Kupfer J. Personality traits, depression and itch in patients with atopic dermatitis in an experimental setting: a regression analysis. Acta Derm Venereol 2014; 94: 20–25.

- Tran BW, Papoiu AD, Russoniello CV, Wang H, Patel TS, Chan YH, et al. Effect of itch, scratching and mental stress on autonomic nervous system function in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 2010; 90: 354–361.

- Kalinska-Bienias A, Piotrowski T, Kowalczyk E, Lesniewska A, Kaminska M, Jagielski P, et al. Actigraphy-measured nocturnal wrist movements and assessment of sleep quality in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a pilot case-control study. Clin Exp Dermatol 2019; 44: 759–765.

- Conrad R, Geiser F, Haidl G, Hutmacher M, Liedtke R, Wermter F. Relationship between anger and pruritus perception in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria and psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008; 22: 1062–1069.

- Ograczyk-Piotrowska A, Gerlicz-Kowalczuk Z, Pietrzak A, Zalewska-Janowska AM. Stress, itch and quality of life in chronic urticaria females. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2018; 35: 156–160.

- Kaaz K, Szepietowski JC, Matusiak Ł. Influence of itch and pain on sleep quality in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol 2018; 98: 757–761.

- Jensen P, Zachariae C, Skov L, Zachariae R. Sleep disturbance in psoriasis: a case-controlled study. Br J Dermatol 2018; 179: 1376–1384.

- Shutty BG, West C, Huang KE, Landis E, Dabade T, Browder B, et al. Sleep disturbances in psoriasis. Dermatol Online J 2013; 19: 1.

- Liu JM, Hsu RJ, Chang FW, Chia-Lun Y, Chun-Fa H, Shu-Ting C, et al. Increase the risk of intellectual disability in children with scabies: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e7108.

- Schricker S, Heider T, Schanz M, Dippon J, Alscher MD, Weiss H, et al. Strong associations between inflammation, pruritus and mental health in dialysis patients. Acta Derm Venereol 2019; 99: 524–529.

- Yngman-Uhlin P, Johansson A, Fernström A, Börjeson S, Edéll-Gustafsson U. Fragmented sleep: an unrevealed problem in peritoneal dialysis patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2011; 45: 206–215.

- Benito de Valle M, Rahman M, Lindkvist B, Björnsson E, Chapman R, Kalaitzakis E. Factors that reduce health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 769–775.e2.

- Cheung AC, Patel H, Meza-Cardona J, Cino M, Sockalingam S, Hirschfield GM. Factors that influence health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci 2016; 61: 1692–1699.

- Montagnese S, Nsemi LM, Cazzagon N, Facchini S, Costa L, Bergasa NV, et al. Sleep-wake profiles in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver Int 2013; 33: 203–209.

- Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Wunsch E, Krawczyk M, Rigopulou EI, Kostrzewa K, Norman GL, et al. Assessment of health related quality of life in polish patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2016; 40: 471–479.

- Altunay İK, Özkur E, Uğurer E, Baltan E, Aydın Ç, Serin E. More than a skin disease: stress, depression, anxiety levels, and serum neurotrophins in lichen simplex chronicus. An Bras Dermatol 2021; 96: 700–705.

- Martín-Brufau R, Corbalán-Berná J, Ramirez-Andreo A, Brufau-Redondo C, Limiñana-Gras R. Personality differences between patients with lichen simplex chronicus and normal population: a study of pruritus. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20: 359–363.

- Martín-Brufau R, Suso-Ribera C, Brufau Redondo C, Corbalán Berná J. Differences between men and women in chronic scratching: a psychodermatologic study in lichen simplex chronicus. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2017; 108: 354–360.

- Yilmaz B, Canan F, Şengül E, Özkurt FE, Tuna SF, Yildirim H. Type D personality, anxiety, depression and personality traits in patients with isolated itching of the external auditory canal. J Laryngol Otol 2016; 130: 50–55.

- Epifanio MS, Ingoglia S, Alfano P, Lo Coco G, La Grutta S. Type D personality and alexithymia: common characteristics of two different constructs. Implications for research and clinical practice. Front Psychol 2018; 9: 106.

- Schneider G, Grebe A, Bruland P, Heuft G, Ständer S. Chronic pruritus patients with psychiatric and psychosomatic comorbidity are highly burdened: a longitudinal study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: e288–e291.

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn, text revision. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2022.