ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Impact of late effects after treatment for bladder cancer with radical cystectomy on Quality of life: a case-control study

Rikke V. Millinga,b, Ninna K. Nielsena,b, Charlotte Graugaard-Jensena,b, Peter Christensenb,c, Helle Pappotd and Jørgen B. Jensena,b

aDepartment of Urology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; bDepartment of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; cDepartment of Surgery,Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; dDepartment of Oncology, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark

ABSTRACT

Background and purpose: The gold standard when treating muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is radical cystectomy (RC), a procedure that holds the potential to affect the function of several pelvic organs, causing an impact on the patient’s Quality of Life (QoL). Knowledge of the late effects following bladder cancer and treatment with RC is sparse. The aim is to describe the incidence of late effects and to investigate the impact on QoL.

Methods: A cross-sectional study using register data in combination with a questionnaire, measuring pelvic organ specific symptoms to treatment and QoL. MIBC patients diagnosed between 2015 and 2020 and able to receive digital mail was invited. For each MIBC patient, 6 age- and gender matched controls were invited. QoL was measured using EORTC-QLQ-C30. The MIBC specific EORTC-QLQ-BLM30 was administered to cases only.

Results: A total of 628 (54.3%) MIBC patients and their 1,204 (37.3%) matched controls responded. Median age was 73. Mean time since RC was 4.9 (SD 2.1) years. Scoring of the functional items on EORTC-QLQ-C30 and overall QoL were similar for cases and controls. Regarding late effects, similar responses were seen on questionnaire data when comparing cases and controls. On registry data, a higher risk of infections and hydronephrosis were seen for cases. A strong correlation between fatigue and impaired QoL was identified.

Interpretation: MIBC patients were more often diagnosed with late effects such as infections and hydronephrosis, compared to controls. In spite of this, MIBC patients overall QoL was equal to that of the controls.

KEYWORDS: Bladder cancer; late effects; quality of life; radical cystectomy

Citation: ACTA ONCOLOGICA 2025, VOL. 64, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.2340/1651-226X.2025.41040.

Copyright: © 2025 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing on behalf of Acta Oncologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Received: 30 July 2024; Accepted: 30 November 2024; Published: 8 January 2025

CONTACT: Rikke Vilsbøll Milling rimill@rm.dk Palle Juul-Jensens Blvd. 99, 8200 Aarhus, Denmark

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.2340/1651-226X.2025.41040

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the 10th most common cancer, affecting males and females in a 4:1 ratio. Bladder cancer can be either non-muscle invasive (NMIBC) or muscle invasive (MIBC). The gold standard when treating high risk NMIBC and MIBC is radical cystectomy (RC) with urinary diversion [1].

In addition to the bladder being removed and a conduit being created from the bowel, RC includes removal of the prostate and the seminal vesicles for men, and for most women, the removal of the anterior vaginal wall, the uterus, and ovaries [2, 3]. Thus, the surgery has the potential to affect or disrupt the function of several pelvic organs, causing a severe impact on the patient’s life, which to some extend can be measured by surveying quality of life (QoL) [4].

Various questionnaires have been developed to measure QoL. In bladder cancer research, the most frequently used generic questionnaires are the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer’s (EORTC) EORTC-QLQ-C30 [5] and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy’s (FACT) FACT-G [6]. These generic questionnaires can be combined with bladder cancer specific questionnaires, most frequently used is the EORTC-QLQ-BLM30 [7] and the FACT-Bl [8]. Furthermore, symptom-specific questionnaires measuring for example sexual health has been developed and the EORTC-SHQ-C22 is used to measure sexual health among cancer patients [9].

Using these instruments, several studies have demonstrated the impact of bladder cancer and its treatment on QoL, which often leads to more deterioration in QoL compared to other pelvic organ cancers [10–12].

One explanation for this, could be the long-term consequences of treatment, also known as late effects. Late effects are defined as complications occurring during treatment and persisting longer than 3 months after the intervention [13]. As the amount of long-term survivors increase, attention towards both research and treatment of late effects has grown. Although the mortality associated with bladder cancer has hardly improved much during the past decade, long-term survivors exist, and they report that the treatment has impacted their lives [14]. Still, knowledge about late effects among bladder cancer survivors is sparse.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe the incidence of late effects following treatment for bladder cancer with RC and to investigate the impact on the patients’ QoL.

Methods

Patient selection

This study is a national cross-sectional register study in combination with a questionnaire survey. The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) was used to identify the study population [15]. We included all Bladder Cancer patients diagnosed between 1st of January 2015 and 31st of December 2020 treated with RC and urinary diversion and still alive on the 17th of August 2022.

For each bladder cancer patient (cases), 6 age- and gender-matched controls were identified in the DNPR.

Demographic data on age, comorbidities, peri- and post-operative complications were obtained from the Central Person Registry (CPR) and DNPR. Additionally, the DNPR was used to obtain details on treatment using the International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 codes (ICD10-code). The tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) stages were obtained from the Danish Cancer Registry (CAR). The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s or dementia registered in the DNPR served as a condition-specific exclusion criteria, allowing for the presence of other malignancies. SurveyXact was used to distribute the electronic questionnaire. The questionnaire was only distributed to those receiving digital mail from the authorities through the Danish digital mailbox system (E-boks). Mails distributed to the digital mailbox are not sent to an email-address, but to the social security number of the citizen. The invitations were distributed to the entire cohort at once. If no response had been registered after 9 days, a reminder was sent.

The study adheres to the General Data Protection Regulations and was reported to the Danish Data Protection Agency (Central Denmark Region, record number: 1-16-02-394-21). In accordance with the Danish legislation, no separate ethical approval was required.

Questionnaires

The survey consisted of the following questionnaires:

The generic QoL questionnaire EORTC-QLQ-C30 and the sexual health questionnaire EORTC-SHQ-C22 were administered to all participants, and the bladder cancer specific questionnaire EORTC-QLQ-BLM30 to cases only. All EORTC questionnaires are scored on a scale from 0 to 100. On EORTC-QLQ-C30, a high score on functional items represents a high QoL. On all EORTC questionnaires, a high score on symptom items represents a high level of symptomatology [5, 9]. To elaborate on erectile function, the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF5) was included [16]. Questions 2–6 were only administered to sexually active responders.

Furthermore, the Bristol Stool Form Scale was included to add a measurements of bowel function on other questionnaires [17].

In addition, selected questions from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) PRO Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) library covering anxiety, depression, concentration, and memory loss were included. These questions were scored from 0 to 4, and a high score indicated high symptomatology.

After each section of questions (urological, sexual, gastrointestinal), the patients were asked to evaluate the impact of their experienced problems on their QoL on a 4-point scale; ‘Not at all’, ‘A little’, ‘Some’, ‘A lot’, this served as an anchor question.

Prior to distribution of the questionnaire, a pilot-study was conducted inviting eight patients who attended the standard post-cystectomy follow-up programme. They completed the questionnaires and were afterwards interviewed about the content and questions asked using a semi-structured approach (For interview-guide, see Supplementary Table 1).

DNPR data

For cases, late effects were defined as diagnoses dated to occur after the date of cystectomy. The index date of a case was applied to their matched controls, thus including only diagnoses registered after the index date.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.2. [18].

The EORTC questionnaires were scored and analysed according to guidelines, omitting missing data [5, 9, 19]. Missing data on the additional questionnaires are presented when relevant and omitted when contributing to a multi-item analysis, removing the multi-item score.

In the analysis of descriptive statistics, the mean and standard deviation were applied to data following a normal distribution, while the median and quartiles (Q1, Q3) were utilised for non-normally distributed data. Frequencies and percentages are presented, especially when reporting on Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROM) results. Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Spearman’s correlations were applied when testing for correlations between PROM symptoms and the Global Health Scale on EORTC-QLQ-C30.

Results

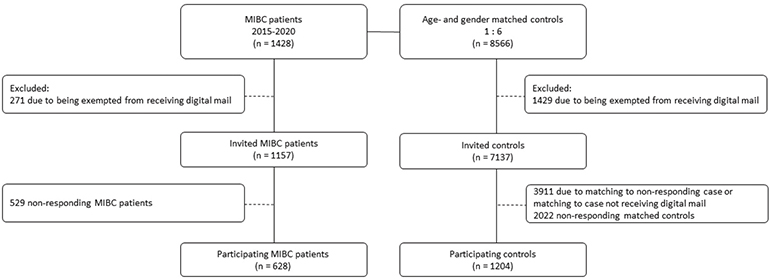

A total of 1,428 bladder cancer patients treated with RC were identified. A total of 271 (19%) patients were excluded due to being exempted from receiving digital mail. A total of 8,566 controls were identified, as two cases had only five matched controls. Among controls, 1,429 (17%) were excluded due to being exempted from receiving digital mail (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of study inclusion process.

Of the invited 1,157 cases, 628 (54.3%) responded. Of their 3,226 invited controls, 1,204 (37.3%) responded. The overall response rate was 41.8%.

Matching for age and sex, we found similar age- and sex proportions. Furthermore, the cohorts matched according to BMI and comorbidity burden, measured by age adjusted Charlson comorbidity index. Cases were more likely to have a history of smoking, compared to controls (p < 0.001). Median age of responding cases was 73 (Q1: 67, Q3: 79). For non-responding cases, median age was 75 (Q1: 67, Q3: 81). Median age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (AA-CCI) was 4 (Q1: 3, Q3: 4) for responding cases and 4 (Q1: 3, Q3: 5) for non-responding cases.

Additional demographic characteristics of the cohort are listed in Table 1. Organ-confined BC was defined as carcinoma in situ (CIS) or T1–T2, N0, M0 at the time of cystectomy. Regarding patients with other pelvic organ cancers, we found 107 (17%) among cases and 96 (8%) among controls (p = 0.36). The most common pelvic cancers found were prostate cancer, found in 97 (15%) of cases and 79 (7%) of controls and rectal cancer, found in 7 (1%) of cases and 7 (0.5%) of controls.

Scoring of the functional items on EORTC-QLQ-C30 and overall QoL were similar for cases and controls. The scores of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 are listed in Table 2. The scores on the functional items were high, indicating good QoL. Missing items to the EORTC-QLQ-C30 ranged from 0 to 3%.

The prevalence of late effects was higher and the subjective burden of urological problems on QoL was evaluated to be higher for cases compared to controls (p < 0.001). Scoring of the multi-item urostomy problems were a median of 11.1 (Q1: 5.55, Q3: 22.22), indicating mild symptomatology (Table 3).

The control cohort was more likely to be sexually active and the reasons for sexual inactivity differed significantly between the groups (p < 0.001), with erectile dysfunction being the most common reason for sexual inactivity among cases (Table 4). No differences in responses of the EORTC-QLQ-SH22 was found on either single- or multi-items. Scoring of the questionnaire were generally low, indicating mild symptomatology for both cases and controls. A difference was observed on the IIEF5, identifying a higher incidence of moderate and severe erectile dysfunction among sexually active cases (14%) compared to controls (6%). Additionally, the impact of sexual problems on QoL was significantly worse for cases compared to controls (p < 0.001).

| Characteristic | Case | Control |

| N = 628 | N = 1204 | |

| Sexually active | 139 (23%) | 568 (51%) |

| Reasons for sexual inactivity | ||

| Lack of desire | 52 (11%) | 76 (12%) |

| Erectile dysfunction | 267 (54%) | 174 (27%) |

| Loss of partner | 9 (2%) | 12 (2%) |

| Pain or discomfort | 52 (11%) | 153 (24%) |

| Other | 83 (17%) | 128 (20%) |

| Missing | 26 (5%) | 93 (15%) |

| EORTC-SHQ-C22 | ||

| Sexual activity | 33.3 (33.3, 66.7) | 33.3 (33.3, 66.7) |

| Decreased libido | 33.3 (0, 33.3) | 0 (0, 33.3) |

| Worries of incontinence during sexual activity | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) |

| Impact of fatigue on sexual activity | 33.3 (0, 33.3) | 33.3 (0, 33.3) |

| Impact of treatment on sexual activity | 66.7 (33.3, 100) | - |

| Partnership | 33.3 (0, 66.7) | 33.3 (0, 33.3) |

| Vaginal dryness | 33.3 (0, 66.7) | 33.3 (0, 66.7) |

| Confidence erection | 100 (33.3, 100) | 33.3 (33.3, 66.7) |

| Body image (male) | 33.3 (0, 66.7) | - |

| Body image (female) | 33.3 (0, 66.7) | - |

| Sexual satisfaction* | 41.7 (20.8, 57.3) | 25 (12.5, 37.5) |

| Sexual pain* | 0 (0, 11.1) | 0 (0, 0) |

| IIEF5 scoring | ||

| Severe ED | 48 (10%) | 21 (3%) |

| Moderate ED | 18 (4%) | 27 (3%) |

| Mild to moderate ED | 12 (3%) | 57 (6%) |

| Mild ED | 13 (3%) | 134 (14.6%) |

| No ED | 11 (2%) | 202 (22%) |

| Missing | 374 (78%) | 472 (51%) |

| Data from DNPR | ||

| Erectile dysfunction | 55 (9%) | 21 (2%) |

| Vaginal dryness | <5 (<1%) | <5 (<1%) |

| Decreased libido | - | - |

| Sexual counselling | - | - |

| Impact of sexual problems on QoL | ||

| Not at all | 206 (33%) | 559 (46%) |

| A little | 187 (30%) | 373 (31%) |

| Some | 148 (24%) | 138 (11%) |

| A lot | 53 (8%) | 32 (3%) |

| Missing | 34 (5%) | 102 (9%) |

| ED: Erectile dysfunction. *Multi-item, n (%), median (Q1, Q3) DNPR: Danish National Patient Registry; IIEF: International Index of Erectile Function. |

||

The symptoms measured on EORTC-QLQ-C30 showed that gastrointestinal problems were mild in both groups (Table 5). Still, the impact of gastrointestinal problems on QoL was significantly worse for cases compared to controls (p < 0.001).

The scores on PRO-CTCAE were low in both groups, correlating with the low prevalence of diagnoses of anxiety and depression identified in DNPR (Table 6). Fatigue and insomnia measured on EORTC-QLQ-C30 were mild and similar in the two groups.

Testing for correlations, we identified one strong correlation between fatigue and Global Health scale (r(149) = -0.62, p < 0.001). The other correlations tested were either very weak, weak, or moderate (See supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the overall QoL were equally high for cases with bladder cancer and controls. However, cases often found that their urinary, sexual, and bowel symptoms all had a higher impact on QoL than controls.

On EORTC-QLQ-C30, there was a tendency towards better physical functioning, cognitive functioning, and social functioning for controls compared to cases. However, the difference is estimated to be small for physical functioning and medium for social- and cognitive functioning [20], and is thus not interpreted to be of significance. The scoring on the questionnaire for cases are similar to that of other studies [10, 12] or even slightly higher [21]. Furthermore, the scores for both cases and controls are similar and even better than the reference data for all cancer patients. The Global Health Scale scores for both cases and controls are higher compared to the reference values for the general population [22]. This finding could potentially be explained by the gap theory or the happy survivor effect, described in psychological research [23, 24]. Both theories describe how accumulated experiences, surviving critical illness and older age can be linked to increased life satisfaction and improved QoL.

The formation of a urostomy, alters the urinary system for cases, resulting in large differences with regard to urological problems between cases and controls. Thus, interpreting the impact of the urostomy correctly by comparison is difficult. The scoring of urostomy problems in this study are similar or lower compared to that of other studies [25], indicating lesser symptomatology. As the urostomy complicates comparison, the search for late effects in DNPR focused on ICD10-codes that could occur in both cases and controls. We found that cases were more prone to develop infectious disease in their urinary tracts as well as hydronephrosis. Infections are a well-known risk following surgical procedures and strictures resulting in hydronephrosis are highly prevalent following RC [26]. The fact that the cases evaluated their urological symptoms to have a greater impact on their QoL, could therefore partially be explained by confirmation bias, where patients correlate their urological symptoms with negativity, as they have experienced great impact on their lives as a result of disease in their urinary tract.

In this study, 24% of cases were sexually active. Similarly, Jubber et al. found that 26% of patients treated with RC or radiotherapy were sexually active compared to 36% for patients treated with transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT) and/or installation therapy [27]. It is well known that RC heavily influences erectile function and orgasmic ability, irrespective of attempting to conduct nerve-sparring surgery, which could explain the tendency to lesser sexual activity among cases compared to controls [28]. This hypothesis is supported by the results, with erectile dysfunction being the most common reason for sexual inactivity, particularly among cases compared to controls. Treatment is available for both men and women, but our data from DNPR shows that neither many responders have a ICD10-code of erectile dysfunction or vaginal dryness nor do they have a ICD10-code for sexual counselling. Considering how many patients report such problems on the questionnaire, our finding could indicate, that sexual problems are rarely discussed with the surgeon. Considering that cases evaluate the impact of sexual problems on QoL significantly worse than controls, our study supports the findings of other studies; the urologist should inform and initiate the conversation concerning sexual problems with the patients in order to reduce this burden [29, 30].

In this study, the PRO data suggests that gastrointestinal problems 5 years after cystectomy are generally mild and no different from that of controls. Interestingly, bladder cancer patients report a higher impact on QoL than controls. Other studies using different questionnaires have identified that flatulence and diarrhea are problems of concern for bladder cancer patients following RC [31, 32]. However, they also found that bowel function improves after surgery and becomes less significant to patients in the long term [33, 34]. The EORTC-QLQ-BLM30 multi-item on abdominal bloating and flatulence, diarrhoea, and constipation were similar to that of other studies [12, 14]. Thus, either the instrument applied fails to accurately describe the symptomatic burden of the patients, or the symptoms improve over time, but the memory of the problems remains with the patients, resulting in confirmation bias when the patient are asked to evaluate the impact of their bowel function on QoL.

The psychological late effects revealed that symptoms were generally mild and there were no differences in PROM data and DNPR data between cases and controls. These findings are surprising, as other studies have identified a correlation between mental health problems and impairment of QoL [35] and that the impact of bladder cancer on mental health often results in diagnoses of anxiety and depression, resulting in higher suicide rates [36]. The requirement for participants in our cohort to be alive and willing to answer the questionnaire may have influenced the psychological outcomes of this study. One could hypothesise, that those struggling with mental health problems might not be willing to participate, resulting in responder bias, which could explain our results. Another potential explanation could be that the median time since cystectomy in our study is 4.9 years. Optimal timing regarding evaluation of impact of symptoms on QoL is up for debate, but Kulaksizoglu and colleagues suggest waiting until after 12 months, based on their finding that patients often return to baseline within the first year [37]. Another study by Cerruto and colleagues found that patients typically improved to levels above baseline 7 years post-surgery [38]. Therefore, our findings might be influenced by the inclusion of long-term survivors who have endured the initial challenging years of the disease and are now less affected.

The differences in proportion of other pelvic organ cancers can mainly be contributed to the differences in prostate cancer, which potentially can be explained due to incidental findings during cystoprostatectomy. Thus, no true differences in the cohorts were identified, aside from tobacco history and the bladder cancer diagnosis, suggesting a well-matched study population.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design limits the possibility to conclude on the timely relation between symptoms and QoL. Secondly, selection bias could occur, as we chose to invite patients who had been diagnosed 3 years or more prior to being invited to participate. Thus, those heavily affected by the diagnosis and treatment within the first 3 years of diagnosis, have not been heard in this study. We speculate that the potential for bias in this study will affect our hypotheses towards the null. Additionally, non-responding cases and controls were generally older and slightly more comorbid than participants, which could potentially influence the results related to QoL. Furthermore, the difference in response rates between cases and controls might also introduce bias due to differential participation, limiting generalisability [39]. The strengths of this study include the size of the population and the ability to provide both subjective data in the form of PROMs and objective data from the DNPR, painting a more detailed picture of the burden experienced by the patients.

Conclusion

This study found a higher risk of late effects such as infections and hydronephrosis for bladder cancer patients compared to a control population. Regarding sexual function, bladder cancer patients are more often experiencing erectile dysfunction and evaluate sexual problems to have higher impact on their QoL compared to controls. Although no higher scores of gastrointestinal problems were identified for cases, patients reported to be more affected by gastrointestinal problems compared to controls. Regarding psychological late effects, mild symptomatology was found, but especially fatigue seems to have a significant negative impact on QoL. Despite having a higher degree of symptomatology, bladder cancer patients’ overall QoL was equal to that of the controls.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by the Danish Cancer Society, Denmark, Grant number: R192-A11536-B3131.

Data availability statement

The corresponding author is willing to provide the scripts used for data analysis upon request. Additionally, the corresponding author will fully cooperate with the editor or their assignees in explaining the data underlying the manuscript. However, due to Danish laws and regulations, the raw data from the Danish National Health Registries cannot be made available. Data from the questionnaires may be accessible in anonymised form, subject to approval by both the editors and the corresponding author, if the intended purpose is deemed reasonable and necessary.

Ethics declaration

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and data collection adhered to the General Data Protection Regulations. The study was reported the Danish Data Protection Agency (Central Denmark Region, record number: 1-16-02-394-21). In accordance with the Danish legislation, no separate ethical approval was required.

ORCID

Rikke Vilsbøll Milling  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2263-2060

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2263-2060

Ninna Kjær Nielsen  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6756-8467

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6756-8467

Charlotte Graugaard-Jensen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2441-1790

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2441-1790

Peter Christensen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6611-3935

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6611-3935

Helle Pappot  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3570-5372

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3570-5372

Jørgen Bjerggaard Jensen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4347-739X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4347-739X

References

[1] Alfred Witjes J, Max Bruins H, Carrión A, Cathomas R, Compérat E, Efstathiou JA, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2023 guidelines. Eur Urol. 2023;85(1):17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.08.016

[2] Westerman ME, Kokorovic A, Wang XS, Lim A, Garcia-Gonzalez A, Seif M, et al. Radical cystectomy and perioperative sexual function: a cross-sectional analysis. J Sex Med. 2020;17(10):1995–2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.015

[3] Clay R, Shaunak R, Raj S, Light A, Malde S, Thurairaja R, et al. Oncological and functional outcomes of organ‐preserving cystectomy versus standard radical cystectomy: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. BJUI Compass. 2023;4(2):135–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/bco2.189

[4] Grobet-Jeandin E, Pinar U, Parra J, Rouprêt M, Seisen T. Health-related quality of life after curative treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2023;20(5):279–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-022-00693-z

[5] Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI J Natl Cancer Instit. 1993;85(5):365–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

[6] Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570

[7] Ripping TM, Rammant E, Witjes JA, Aaronson NK, Van Hemelrijck M, Van Hoogstraten LMC, et al. Validation and reliability of the Dutch version of the EORTC QLQ-BLM30 module for assessing the health-related quality of life of patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2022;20(1):171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-02064-z

[8] Degboe A, Ivanescu C, Rohay JM, Turner RR, Cella D. Validity and performance of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bladder (FACT-Bl) among advanced urothelial cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(11):4189–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04709-0

[9] Greimel E, Nagele E, Lanceley A, Oberguggenberger AS, Nordin A, Kuljanic K, et al. Psychometric validation of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Quality of Life Questionnaire Sexual Health (EORTC QLQ-SH22). Eur J Cancer. 2021;154:235–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.003

[10] Rogers Z, Glaser A, Catto JWF, Bottomley S, Jubber I, Kotwal S, et al. Health‐related quality of life after a diagnosis of bladder cancer: a longitudinal survey over the first year. BJU Int. 2024;133(4):460–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.16242

[11] Smith AB, Jaeger B, Pinheiro LC, Edwards LJ, Tan HJ, Nielsen ME, et al. Impact of bladder cancer on health‐related quality of life. BJU Int. 2018;121(4):549–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14047

[12] Catto JWF, Downing A, Mason S, Wright P, Absolom K, Bottomley S, et al. Quality of life after bladder cancer: a cross-sectional survey of patient-reported outcomes. Eur Urol. 2021;79(5):621–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2021.01.032

[13] Schmidt ME, Goldschmidt S, Hermann S, Steindorf K. Late effects, long‐term problems and unmet needs of cancer survivors. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(8):1280–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34152

[14] Mak KS, Smith AB, Eidelman A, Clayman R, Niemierko A, Cheng JS, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(5):1028–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.08.023

[15] Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;2015:449–90. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S91125

[16] Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00238-0

[17] Blake MR, Raker JM, Whelan K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea‐predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut. 2016;44(7):693–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13746

[18] Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022.

[19] Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. Brussels The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001.

[20] Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, De Castro G, Martyn St-James M, Fayers PM, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. Eur J Cancer. Brussels, 2012;48(11):1713–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.059

[21] Kretschmer A, Grimm T, Buchner A, Jokisch F, Ziegelmüller B, Casuscelli J, et al. Midterm health-related quality of life after radical cystectomy: a propensity score-matched analysis. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6(4):704–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2019.02.017

[22] Fayers P, Weeden, S., Curran, D. EORTC QLQ–C30 reference values manual. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 1998.

[23] Segerstrom SC, Combs HL, Winning A, Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The happy survivor? Effects of differential mortality on life satisfaction in older age. Psychol Aging. 2016;31(4):340–5. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000091

[24] Glaser AW. Resilience of men and the gap hypothesis of quality of life: health utility outcome measurement in prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;76(6):752–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2019.07.046

[25] Clements MB, Atkinson TM, Dalbagni GM, Li Y, Vickers AJ, Herr HW, et al. Health-related quality of life for patients undergoing radical cystectomy: results of a large prospective cohort. Eur Urol. 2022;81(3):294–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2021.09.018

[26] Brandt SB, Kingo PS, Laurberg JR, Lam GW, Jensen JB. Definition of benign ureteroenteric anastomotic strictures in ileal conduits after radical cystectomy: experience from a single center and previously published literature. Urology. 2024;187:139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2024.02.044

[27] Jubber I, Rogers Z, Catto JW, Bottomley S, Glaser A, Downing A, et al. Sexual activity, function and dysfunction after a diagnosis of bladder cancer. J Sex Med. 2022;19(9):1431–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.06.016

[28] Modh RA, Mulhall JP, Gilbert SM. Sexual dysfunction after cystectomy and urinary diversion. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11(8):445–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2014.151

[29] Pederzoli F, Campbell JD, Matsui H, Sopko NA, Bivalacqua TJ. Surgical factors associated with male and female sexual dysfunction after radical cystectomy: what do we know and how can we improve outcomes? Sex Med Rev. 2018;6(3):469–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.11.003

[30] Gupta N, Kucirka LM, Semerjian A, Wainger J, Pierorazio PM, Herati AS, et al. Comparing provider-led sexual health counseling of male and female patients undergoing radical cystectomy. J Sex Med. 2020;17(5):949–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.025

[31] Hupe MC, Vahlensieck W, Ozimek T, Struck JP, Hennig MJP, Tezval H, et al. Diarrhea and flatulence are major bowel disorders after radical cystectomy: Results from a cross-sectional study in bladder cancer patients. Urol Oncol. 2018;36(5):237.e1–.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.12.014

[32] Goldberg H, Baniel J, Mano R, Rotlevy G, Kedar D, Yossepowitch O. Orthotopic neobladder vs. ileal conduit urinary diversion: a long-term quality-of-life comparison. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2016;34(3):121.e1–.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.10.006

[33] Asanad K, Nazemi A, Ghodoussipour S, Ladi-Seyedian S, Nassiri N, Wayne K, et al. Evaluation of bowel function following radical cystectomy and urinary diversion using two validated questionnaires: what are the effects on quality of life? Urology. 2021;156:279–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2021.04.044

[34] Gellhaus PT, Cary C, Kaimakliotis HZ, Johnson CS, Weiner M, Koch MO, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life outcomes following radical cystectomy. Urology. 2017;106:82–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.03.053

[35] Taarnhøj GA, Johansen C, Lindberg H, Basch E, Dueck A, Pappot H. Patient reported symptoms associated with quality of life during chemo‐ or immunotherapy for bladder cancer patients with advanced disease. Cancer Med. 2020;9(9):3078–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2958

[36] Guo Z, Gu C, Li S, Gan S, Li Y, Xiang S, et al. Incidence and risk factors of suicide among patients diagnosed with bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Oncol. 2021;39(3):171–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.11.022

[37] Kulaksizoglu H, Toktas G, Kulaksizoglu IB, Aglamis E, Unlüer E. When should quality of life be measured after radical cystectomy? Eur Urol. 2002;42(4):350–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00351-2

[38] Cerruto MA, D’Elia C, Cacciamani G, De Marchi D, Siracusano S, Iafrate M, et al. Behavioural profile and human adaptation of survivors after radical cystectomy and ileal conduit. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-46

[39] Aigner A, Grittner U, Becher H. Bias due to differential participation in case-control studies and review of available approaches for adjustment. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191327. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191327