ORIGINAL REPORT

Germline BRCA testing in Denmark following invasive breast cancer: Progress since 2000

Aleksandar M. Kostova  , Maj-Britt Jensenb

, Maj-Britt Jensenb  , Bent Ejlertsenb,c

, Bent Ejlertsenb,c  , Mads Thomassend,e,f

, Mads Thomassend,e,f  , Maria Rossingc,g

, Maria Rossingc,g  , Inge S. Pedersenh,i,j

, Inge S. Pedersenh,i,j  , Annabeth H. Petersenk

, Annabeth H. Petersenk  , Lise Lotte Christensenl

, Lise Lotte Christensenl  , Karin A.W. Wadtc,m

, Karin A.W. Wadtc,m  and Anne-Vibeke Lænkholma,c

and Anne-Vibeke Lænkholma,c

aDepartment of Surgical Pathology, Zealand University Hospital, Roskilde, Denmark; bDanish Breast Cancer Group, Department of Oncology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Denmark; cDepartment of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark; dDepartment of Clinical Genetics, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark; eHuman Genetics, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; fClinical Genome Center, University of Southern Denmark and Region of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; gDepartment of Genomic Medicine, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark; hDepartment of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark; iDepartment of Molecular Diagnostics, Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark; jClinical Cancer Research Center, Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark; kDepartment of Clinical Genetics, Vejle Hospital, University Hospital of Southern Denmark, Denmark; lDepartment of Molecular Medicine (MOMA), Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; mDepartment of Clinical Genetics, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark

ABSTRACT

Background and purpose: Despite advancements in genetic testing and expanded eligibility criteria, underutilisation of germline testing for pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA) remains evident among breast cancer (BC) patients. This observational cohort study presents real-world data on BRCA testing within the context of clinical practice challenges, including incomplete family history and under-referral.

Material and methods: From the Danish Breast Cancer Group (DBCG) clinical database, we included 65,117 females with unilateral stage I–III BC diagnosed in 2000–2017, of whom 9,125 (14%) were BRCA tested. Test results spanned from 1999 to 2021. We evaluated test rates overall and in three diagnosis periods. In logistic regression models, we examined the correlation between a BRCA test and patients’ age, residency region, receptor status, and diagnosis period.

Results: Test rates rose most significantly among patients aged under 40 years, increasing from 47% (2000–2005) to 88% (2012–2017), albeit with regional discrepancies. Test timing shifted in recent years, with most results within 6 months of BC diagnosis, primarily among the youngest patients. BRCA test rates were higher for oestrogen receptor-negative/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative BC (25% in 2000–2005 vs. 38% in 2012–2017), and these findings were confirmed in multivariate regression models.

Interpretation: Our results indicate a critical need for an intensified focus on BRCA testing among BC patients older than 40, where a mainstreamed testing approach might overcome delayed or missed testing. Current DBCG guidelines recommend BRCA testing of all BC patients younger than 50 years, while a general recommendation for older patients is still missing.

KEYWORDS: Genetic testing; hereditary breast cancer; pathogenic variants; Danish Breast Cancer Group

Citation: ACTA ONCOLOGICA 2025, VOL. 64, 147–155. https://doi.org/10.2340/1651-226X.2025.42418.

Copyright: © 2025 The Author(s). Published by MJS Publishing on behalf of Acta Oncologica. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Received: 4 November 2024; Accepted: 15 January 2025; Published: 28 January 2025

CONTACT Anne-Vibeke Lænkholm anlae@regionsjaelland.dk Department of Surgical Pathology, Sygehusvej 9-11, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark

Competing interests and funding: AK, AVL: Institutional and personal grants (presentation) from AstraZeneca; AVL: Advisory board MSD and economic support for congress attendance from Daiichi Sankyo (DS) and AZ; MJ: Meeting expenses and advisory board, Novartis; BE: institutional grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche; meeting expenses from MSD and DS; advisory boards organised by Eli-Lilly and Medac; IP: Personal grant (presentation): AstraZeneca. KW: Personal grant (presentation), Seagen Denmark. MT, MR, and LLC report no conflicts of interest.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca, The Danish Cancer Society, Region Zealand and Region of Southern Denmark Research Foundation, Karen A. Tolstrup Foundation, and Astrid Thaysen Foundation.

Introduction

Germline testing of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes (BRCA) has been well-established for more than two decades for women with invasive breast cancer (BC) [1]. Rapid progress in next-generation sequencing (NGS) has made genetic testing faster and more cost-efficient and broadened the criteria for germline testing, thereby increasing the number of eligible patients [2–4]. Patients with pathogenic variants (PV) in BRCA (BRCA carriers) often present at a younger age than non-BRCA carriers and have an increased risk of contralateral BC and ovarian cancer (OC) [5]. Consequently, BRCA carriers are offered risk-managing programs with intensified follow-up and risk-reducing surgery (contralateral mastectomy alone or in sequence with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) [1, 5, 6]. Current recommendations for genetic testing from the Danish Breast Cancer Group (DBCG) are consistent with national guidelines across Europe and focus on the family predisposition, early age onset of BC (under 50 years), bilateral BC, Triple Negative (TNBC), that is, oestrogen receptor-negative (ER-), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative and/or basal-like molecular subtype, BC and OC in the same patient and male BC [4, 7]. Recently, several international guidelines have broadened the inclusion criteria, recommending BRCA testing to all newly diagnosed BC patients when 65 years or younger, to candidates for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) therapy, and patients with TNBC [8–10]. Similarly, testing women under the age of 60 with BC is recommended in Norway based on a 90% sensitivity for BRCA PV [11, 12].

Underdiagnosis of BRCA among patients with BC has been in focus in recent years, suggesting that up to half of BRCA carriers do not meet current guidelines and mainstreamed genetic testing is highly recommended [13–16]. In other Nordic countries, recent studies emphasised the risk of missing, especially BRCA2 carriers, and showed unequal BRCA testing rates, which differed among all patient groups and geography [11, 17]. Previous reporting on BRCA testing rates has been based on patient questionnaires or cross-sectional study estimates, and the effectiveness of testing criteria is still unclear [16, 18, 19]. In the context of the clinical day-to-day practice challenges, including incomplete family history and under-referral, documenting real-world data on BRCA testing becomes particularly relevant.

In this nationwide observational cohort study, we aimed to describe BRCA testing trends among stage I–III unilateral BC patients in the five Danish regions from 2000 to 2017, based on the hypothesis of increased accessibility for BRCA testing over time. Specifically, we aimed to assess testing rates in patients under 40 and those with TNBC, aligning with Danish guidelines in the study period.

Patients and methods

Cohort

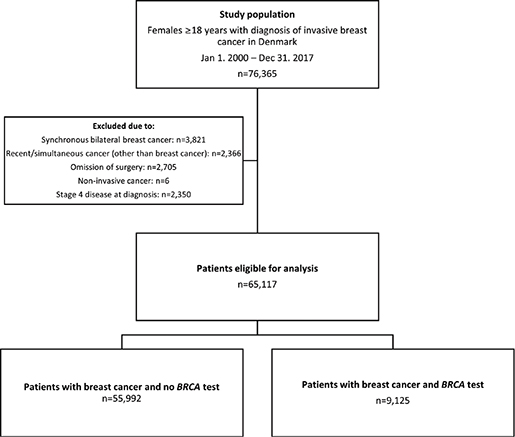

From the clinical database of the DBCG, we gathered a cohort of 76,365 females aged 18 years or older with a biopsy or primary surgical specimen with BC between Jan 1, 2000, and Dec 31, 2017. We linked primary data with data from the Danish Pathology Data Bank, the Danish Cancer Registry, and the Danish National Patient Registry using the central personal register number, a unique identifier assigned to all Danish residents at birth or immigration [20–23]. We excluded 11,248 patients (Figure 1): 3,821 due to synchronous bilateral BC, 2,350 due to stage IV disease at or within 90 days after diagnosis, 2,705 due to the omission of surgery, six due to non-invasive disease, and 2,366 due to previous or simultaneous invasive cancer (other than BC) within 200 days after diagnosis. Long-term survivors, surpassing 9.5 years from another invasive cancer diagnosis, were not excluded. The study complies with the STROBE guidelines for reporting [24].

Genetic test results

BRCA testing was implemented for diagnostic purposes in 1997 at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital, and in 1999 at a national level [25]. The five laboratories (Dept. of Genomic Medicine, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet; Dept. of Clinical Genetics, Odense University Hospital; Dept. of Molecular Diagnostics, Aalborg University Hospital, Dept. of Clinical Genetics, Vejle Hospital; and Dept. of Molecular Medicine (MOMA), Aarhus University Hospital) performed BRCA testing. Since 2011, the analytic platform was NGS gene panel testing, replacing Sanger sequencing. A detailed description of the Danish national concerted efforts of BRCA classification has been published previously [25]. BRCA test results, including the requisition date, were uploaded to the DBCG repository.

Missing data on BRCA test results was retrieved from the five laboratories before the statistical analysis. The oldest result was maintained in the case of multiple testing (e.g., screening test after a previous predictive test result). New results were only considered in the case of variant reclassification. The patients in this study were tested from Sep 1999 to Dec 2021.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R for Windows, version 4.3.2. We have summarised data using frequency counts and percentages in Table 1. The median age was calculated together with the interquartile range (IQR). ER and HER2 were analysed together since guidelines focus on TNBC. PR is not scored routinely in Denmark; hence, TNBC was defined as ER-negative/HER2-negative.

| Total | Year of diagnosis | |||||||||||

| 2000–2005 | 2006–2011 | 2012–2017 | ||||||||||

| No. | w/Test | (%) | No. | w/Test | (%) | No. | w/Test | (%) | No. | w/Test | (%) | |

| Overall | 65117 | 9125 | (14) | 18682 | 1891 | (10) | 23405 | 3122 | (13) | 23030 | 4112 | (18) |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| North | 5907 | 699 | (12) | 1479 | 140 | (9) | 2237 | 263 | (12) | 2191 | 296 | (14) |

| Central | 12668 | 1630 | (13) | 3257 | 294 | (9) | 4694 | 602 | (13) | 4717 | 734 | (16) |

| Southern | 15747 | 2426 | (15) | 4948 | 566 | (11) | 5604 | 817 | (15) | 5195 | 1043 | (20) |

| Capital | 20937 | 3040 | (15) | 6277 | 600 | (10) | 7195 | 989 | (14) | 7465 | 1451 | (19) |

| Zealand | 9858 | 1330 | (13) | 2721 | 291 | (11) | 3675 | 451 | (12) | 3462 | 588 | (17) |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| 18–39 | 2827 | 2043 | (72) | 873 | 409 | (47) | 937 | 744 | (79) | 1017 | 890 | (88) |

| 40–59 | 26224 | 5414 | (21) | 8197 | 1237 | (15) | 9142 | 1759 | (19) | 8885 | 2418 | (27) |

| ≥ 60 | 36066 | 1668 | (5) | 9612 | 245 | (3) | 13326 | 619 | (5) | 13128 | 804 | (6) |

| Histologic type | ||||||||||||

| Ductal | 52125 | 7601 | (15) | 15042 | 1563 | (10) | 18900 | 2647 | (14) | 18183 | 3391 | (19) |

| Lobular | 7059 | 753 | (11) | 2168 | 185 | (9) | 2317 | 232 | (10) | 2574 | 336 | (13) |

| Other or unknown | 5933 | 771 | (13) | 1472 | 143 | (10) | 2188 | 243 | (11) | 2273 | 385 | (17) |

| ER/HER2 1 | ||||||||||||

| ER-/HER2- | 5281 | 1600 | (30) | 915 | 229 | (25) | 2170 | 538 | (25) | 2196 | 833 | (38) |

| ER-/HER2+ | 2638 | 527 | (20) | 629 | 123 | (20) | 1178 | 212 | (18) | 831 | 192 | (23) |

| ER-/ HER2 Unknown | 2611 | 161 | (6) | 2199 | 126 | (6) | 375 | 31 | (8) | 37 | 4 | (11) |

| ER+/HER2- | 36254 | 5135 | (14) | 2602 | 731 | (28) | 15311 | 1880 | (12) | 17341 | 2524 | (15) |

| ER+/HER2+ | 4894 | 1088 | (23) | 701 | 219 | (31) | 1905 | 337 | (18) | 2288 | 532 | (23) |

| ER+/HER2 Unknown | 13855 | 604 | (4) | 11420 | 460 | (4) | 2257 | 120 | (5) | 178 | 24 | (13) |

| ER Unknown | 584 | 10 | (2) | 216 | 3 | (1) | 209 | 4 | (2) | 159 | 3 | (2) |

| Malign. grade | ||||||||||||

| Grade I | 16966 | 1751 | (10) | 4846 | 436 | (9) | 6718 | 694 | (10) | 5402 | 621 | (11) |

| Grade II | 26380 | 3481 | (13) | 7266 | 695 | (10) | 9205 | 1187 | (13) | 9909 | 1599 | (16) |

| Grade III | 13787 | 2789 | (20) | 3948 | 524 | (13) | 4801 | 911 | (19) | 5038 | 1354 | (27) |

| Not graded | 7984 | 1104 | (14) | 2622 | 236 | (9) | 2681 | 330 | (12) | 2681 | 538 | (20) |

| Nodal status2 | ||||||||||||

| Negative | 36494 | 5045 | (14) | 9104 | 950 | (10) | 12722 | 1616 | (13) | 14668 | 2479 | (17) |

| 1–3 positive LN | 17751 | 2581 | (15) | 5552 | 603 | (11) | 6849 | 1008 | (15) | 5350 | 970 | (18) |

| ≥ 4 positive LN | 8157 | 1091 | (13) | 3282 | 332 | (10) | 3014 | 415 | (14) | 1861 | 344 | (18) |

| FNA positive | 1151 | 361 | (31) | 12 | 2 | (17) | 348 | 68 | (20) | 791 | 291 | (37) |

| Unknown | 1564 | 47 | (3) | 732 | 4 | (1) | 472 | 15 | (3) | 360 | 28 | (8) |

| Tumour size3 | ||||||||||||

| 0–10 mm | 12824 | 1681 | (13) | 2763 | 305 | (11) | 4809 | 643 | (13) | 5252 | 733 | (14) |

| 11–20 mm | 27004 | 3824 | (14) | 7590 | 845 | (11) | 9678 | 1301 | (13) | 9736 | 1678 | (17) |

| 21–50 mm | 22416 | 3168 | (14) | 7405 | 660 | (9) | 7920 | 1044 | (13) | 7091 | 1464 | (21) |

| >50 mm | 2368 | 399 | (17) | 774 | 69 | (9) | 794 | 118 | (15) | 800 | 212 | (27) |

| Unknown | 505 | 53 | (10) | 150 | 12 | (8) | 204 | 16 | (8) | 151 | 25 | (17) |

| Comorbidity4 | ||||||||||||

| CCI 0 | 52064 | 8046 | (15) | 15255 | 1725 | (11) | 18695 | 2747 | (15) | 18114 | 3574 | (20) |

| CCI 1 | 8105 | 755 | (9) | 2107 | 119 | (6) | 2936 | 264 | (9) | 3062 | 372 | (12) |

| CCI ≥ 2 | 4948 | 324 | (7) | 1320 | 47 | (4) | 1774 | 111 | (6) | 1854 | 166 | (9) |

| 1 HER2- = HER2-negative, HER2+ = HER2-positive; 2 Nodal status applies to clinical node status (radiologically determined with ultrasound or MRI) or fine-needle aspirate (FNA) from axillary nodes for patients referred to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Otherwise, the pathological nodal status was applied. If axillary dissection was performed and no lymph nodes (LNs) were found, the nodal status was determined as ‘Unknown’; 3 For patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the clinical tumour size (radiologically determined by ultrasound or MRI) was applied. For patients operated upfront, the pathological tumour size was applied; 4 Charlson’s Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated using ICD-8 and ICD-10 codes for 19 chronic diseases recorded during hospital contacts in the 10 years before the BC diagnosis and were retrieved from the Danish National Patient Registry. | ||||||||||||

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression (LR) models with the binary outcome BRCA test (yes vs. no) were applied to present odds ratios (ORs) according to age and year at diagnosis, region of residency, and receptor status. Other tumour characteristics not directly referred to in the guidelines for genetic testing were not included in the models. We evaluated the interaction terms between age at diagnosis and year of diagnosis, and receptor status and year of diagnosis. Overall p-values were derived from Likelihood-ratio tests, where a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

We conducted Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests. In all tests, the p-values were below 0.05, indicating a poor fit, except for the multivariate model, including interaction terms of age and year of diagnosis, with a p-value of 0.13, suggesting a good predictive model for BRCA testing.

Results

Study cohort

Between Jan 1, 2000 and Dec 31, 2017, 76,365 women were diagnosed with BC in Denmark, and 65,117 (85%) were eligible for the study (Figure 1). Median age at diagnosis was 61 years (IQR 52–69), and the majority (80%) of patients (Table 1) were non-comorbid and diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast with ER+/HER2-negative status (56%). Tumours were most frequently malignancy grade II (41%). Forty-two per cent of patients had node-positive disease. Most tumours measured between 11 and 20 mm (41%).

Testing distribution

One or more tests were linked to 9,125 (14%) patients (Table 1). Test rates increased from 10% of patients diagnosed in 2000–2005 to 18% of patients diagnosed in 2012–2017. The median age was 48 years (40–56). Among patients who were 18–39 years (4% of the cohort) at diagnosis, 72% were tested compared to 21% of those aged 40–59 years (40%) and 5% of those 60 years or older (55%) (Table 1).

Overall, 30% of patients with TNBC had a BRCA test, with test rates increasing from 25% in the first period to 38% in the final period. BRCA test rates were higher in HER2-positive BC (20–23%) compared to 14% in the most frequent receptor combination, ER+/HER2-normal. In the case of unknown receptor status, test rates were low. However, the proportion of patients with unknown HER2 status decreased drastically after 2006. We observed increasing test rates with higher malignancy grade and larger tumour size and decreasing test rates with increasing comorbidity index. Test rates of around 14% were observed across groups of nodal status. Across the five Danish regions, test rates were around 10% initially. In the final period, test rates increased to 14–20%, with regional differences widening, as shown in Table 1.

Test timing

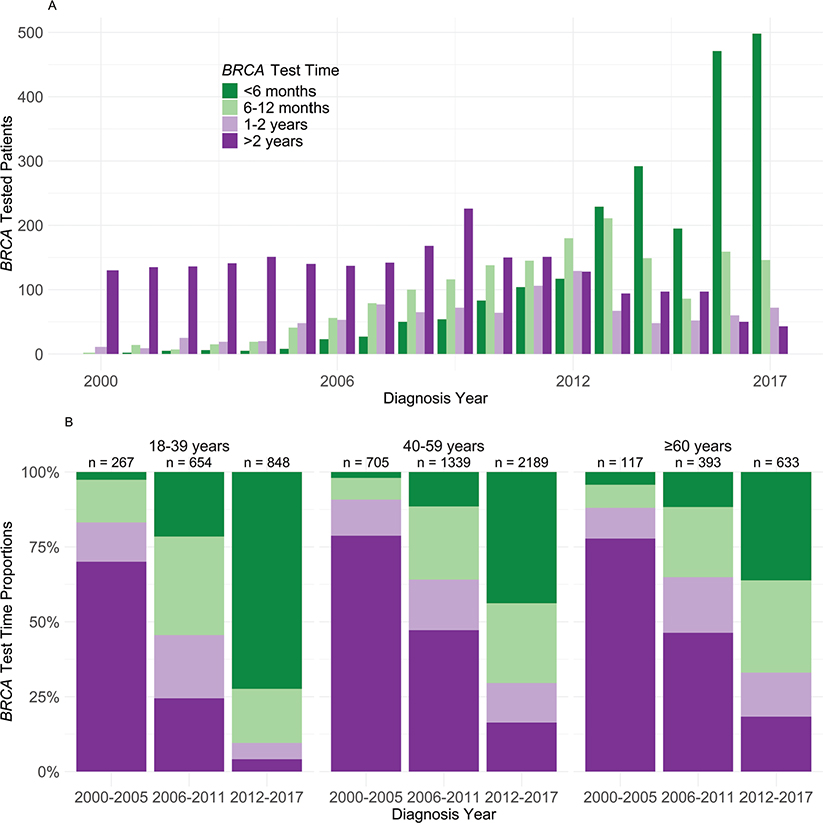

Among the 9,125 women with a BRCA test, only 173 (2%) women were tested before BC diagnosis, while 7,145 (78%) were tested at or after BC diagnosis and before a second event, defined as any BC recurrence, other malignancy, or death. Lastly, 1,807 (20%) were tested after a second event. Among the 7,145 tested before a second event, test results were available for 2,169 (30%) available within 6 months, 1,663 (18%) after 6 to less than 12 months, 997 patients (11%) between the first and second year, and 2,316 (25%) more than 2 years after diagnosis. Among these 7,145, 720 (10%) had a confirmed BRCA PV: 267 (15%) of patients aged 18–39, 378 (12%) of those aged 40–59, and 75 (7%) of those aged 60 and older.

The number of patients with available results within 6 months after diagnosis, reflecting timely testing, rose from zero in 2000 to 498 in 2017 (Figure 2A). More than 70% of patients aged under 40 and diagnosed between 2012 and 2017 received timely testing, compared to less than half of those aged 40 and older (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. (a) BRCA test timing according to year of BC diagnosis among 7,145 patients with BRCA test after unilateral stage I–III BC and before a second event. (b) Distribution of BRCA test timepoint by age and year of diagnosis, among 7,145 patients with BRCA test after unilateral stage I–III BC and before a second event.

Logistic regression models

In univariate LR models, we found a significant correlation between patients referred for BRCA testing and: age at diagnosis, region of residency, year of diagnosis, and receptor status (all p-values < 0.0001). Table 2 shows OR for patients having a BRCA test, where OR > 1 favoured BRCA testing. Testing probability was significantly lower (p < 0.0001) for patients aged 40–59 years (OR = 0.10 [0.09–0.11]) and 60 years or older (OR = 0.02 [0.02–0.02]) compared to the reference age group 18–39. ORs for BRCA testing nearly doubled for the diagnosis period 2012–2017 (OR = 1.93 [1.83–2.05]) compared to the reference period 2000–2005. Residency in other regions besides Southern Denmark and the Capital region showed a significantly lower probability of BRCA testing (p < 0.0001). Compared to TNBC, other receptor combinations showed lower testing probability (p < 0.0001).

Similar estimates for BRCA testing probabilities were estimated in the multivariate LR-model. However, the increased ORs for testing in later periods, compared to 2000–2005, were highly modulated by the receptor status, correlated with the decrease of HER2 unknown from 67% in the first period to 1% in the last (Table 1). In the multivariate LR model (Table 2), the ORs dropped to 0.87 [0.80–0.94] in the second diagnosis period, while OR increased again in the last diagnosis period (1.22 [1.13–1.33]).

In interaction tests, we explored BRCA testing probabilities according to age at diagnosis and receptor status over time (Table 3). There was strong evidence for interactions (p < 0.0001), showing that increasing testing odds over time was primarily driven by increased testing in the youngest age group and in patients with TNBC (OR = 4.78 and OR = 3.63, respectively), while testing odds did not increase significantly for patients over 40 at diagnosis.

| Diagnosis year | 2000–2005 | 2006–2011 | 2012–2017 | P | ||

| Age at diagnosis1 | Odds ratio | [95% CI] | Odds ratio | [95% CI] | < 0.0001 | |

| 18–39 | Ref | 2.75 | [2.21–3.41] | 4.78 | [3.77–6.07] | |

| 40–59 | Ref | 0.71 | [0.65–0.78] | 1.06 | [0.97–1.16] | |

| ≥ 60 | Ref | 0.79 | [0.68–0.93] | 0.96 | [0.82–1.13] | |

| ER/HER22 | Odds ratio | [95% CI] | Odds ratio | [95% CI] | < 0.0001 | |

| ER-/HER2- | Ref | 1.48 | [1.22–1.78] | 3.63 | [3.00–4.38] | |

| ER-/HER2+ | Ref | 1.28 | [0.99–1.67] | 1.83 | [1.38–2.45] | |

| ER+/HER2- | Ref | 0.71 | [0.71–0.97] | 0.87 | [0.80–0.96] | |

| ER+/HER2+ | Ref | 0.93 | [0.81–1.21] | 1.25 | [1.03–1.54] | |

| Unknown | Ref | 2.16 | [1.75–2.66] | 1.79 | [1.05–3.05] | |

| CI: confidence interval. 1 Odds ratios for the interaction term of age at diagnosis and diagnosis year in multivariate LR model, adjusted for region of residency and receptor status; 2 Odds ratios for the interaction term of receptor status and diagnosis year in the multivariate LR model, adjusted for region of residency and age at diagnosis. |

||||||

HER2-positive status was related to increasing BRCA testing odds only in the most recent period, irrespective of the ER status. The frequent receptor combination (ER+/HER2-negative) did not correlate with increasing odds for BRCA testing. Table 4 shows test rates for age and receptor status combination for the first and latest time periods. Test rates increased over time for patients under 40 years, regardless of their receptor status and for TNBC across all age groups.

| Age at diagnosis | 2000–20051 | 2012–20172 | ||||||||||

| 18–39 | 40–59 | ≥ 60 | 18–39 | 40–59 | ≥ 60 | |||||||

| No. | % Test | No. | % Test | No. | % Test | No. | % Test | No. | % Test | No. | % Test | |

| ER/HER2 | ||||||||||||

| ER-/HER2- | 122 | 63 | 505 | 25 | 288 | 9 | 254 | 92 | 848 | 52 | 1094 | 15 |

| ER-/HER2+ | 69 | 57 | 331 | 21 | 229 | 6 | 72 | 89 | 357 | 29 | 402 | 6 |

| ER+/HER2- | 218 | 67 | 1608 | 32 | 776 | 9 | 501 | 86 | 6530 | 24 | 10310 | 5 |

| ER+/HER2+ | 114 | 61 | 415 | 33 | 172 | 6 | 177 | 88 | 1038 | 31 | 1073 | 5 |

| Unknown | 350 | 22 | 5338 | 7 | 8147 | 1 | 13 | 62 | 112 | 15 | 249 | 2 |

| 1 No. = 18,682, 2 No. = 23,030. | ||||||||||||

Discussion

Among 65,117 Danish females diagnosed with unilateral early BC between 2000 and 2017, 14% had undergone BRCA testing between 1999 and 2021. Test rates increased from 10% in 2000–2005 to 18% in 2012–2017, with the most prominent increase observed in females younger than 40 at BC (from 50 to 88% in the same periods). This increase reflects the recommendations for testing BC patients aged 40 or younger in the last diagnosis period, and it was higher than the 66% test rate reported among this patient group in Georgia and California from 2013 to 2017 [18]. An even lower test rate of 23% was reported in the 2015 Cancer Control Module of the US National Health Interview Survey among BC patients diagnosed before age 45 [19]. However, the results were based on self-reported survey answers from a small sample size (n = 325) with a significant risk of recall bias [19].

Despite the significant increase in testing among younger patients, the rise was less prominent among older patients, leading to lower overall test rates. Consequently, less than 20% of Danish BC patients were tested in the most recent period, revealing lower rates compared to other countries [11, 18, 19]. In Norway, 35% of women diagnosed with BC in 2016 and 2017 were tested, corresponding to 75% of patients who met the national test guidelines [11]. The high test rates in Norway were attributed to the direct offering of the BRCA test to patients by surgeons or oncologists, a practice known as mainstreaming [11]. The incidence of bilateral BC in the Norwegian study was 1%, but the cases were not specified as synchronous [11]. In our study, this rate was 5%, and including these patients still would not match test rates in Norway. BRCA testing rates were highest in the Capital and Southern Regions hosting the University Hospitals in Copenhagen, Rigshospitalet, and Odense. Limited focus on BRCA testing and longer travel distances may explain lower test rates in smaller centres. Additionally, Region Zealand did not offer oncogenetic counselling before 2017, where patients were mainly referred to Rigshospitalet. Several Danish centres currently provide genetic counselling via video after local blood sample collection to accommodate long-distance patients. Implementing the Norwegian or similar guidelines in Denmark will likely increase BRCA testing and associated costs. The Danish healthcare system is publicly financed and requires all recommendations to be accepted by the Danish Regions and included in their economic frameworks [26]. Since 2013, multigene-panel testing has been implemented universally in Denmark and will increase the variants of unknown significance (VUS) and PV rates in moderate-risk genes [18, 25, 27]. By implementing mainstreamed BRCA testing, surgeons and oncologists could share normal results, referring only patients with PV or VUS who require genetic counselling expertise.

A cost-effective population-based test for three founder mutations has since 1996 in Poland resulted in BRCA testing of 500,000 people, but the study did not report specific test rates among patients with BC [28]. The absence of widespread founder mutations prohibits a similar strategy from being successful in Denmark [29].

We observed a significant shift in test timing as none of the patients in 2000 received their test results within 6 months, while most patients (65%) diagnosed in the last two study years received timely BRCA results. Similar BRCA testing time trends have been observed by others [18]. Despite the well-established predictive BRCA testing in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC) families in Denmark, evidence shows that very few individuals are linked to an HBOC family [25, 29]. This fact is underscored by the low number of patients in our cohort who had undergone BRCA testing before a BC diagnosis.

In our study, patients with TNBC were tested more frequently than those with other receptor subtypes (30% vs. 2–23%), with test rates increasing from 25% in 2000–2005 to 38% in 2012–2017. The increase is likely due to the 2016 DBCG guidelines recommending genetic testing for TNBC patients under 60 and might be most pronounced in the last study year [30]. Multivariable LR models suggested a similar correlation, showing an increased probability for BRCA testing in patients with TNBC diagnosed in 2006–2011, likely reflecting awareness of the higher prevalence of TNBC among BRCA carriers [31]. We also observed increased BRCA testing for HER2-positive BC, although not as high as for TNBC. However, these correlations seem highly modulated by, first, changed national diagnostic practices, with HER2 routinely scored since 2006 and second, the analysis of ER unknown and HER2 unknown as one group in the LR models. ER unknown proportions were constant over time, while HER2 unknown decreased rapidly. Unlike other known ER and HER2 combinations, where the incidence doubled after routinely scoring HER2, the incidence of patients with the most common receptor combination, ER+/HER2-negative, increased sixfold after 2005 (Table 1). Consequently, the observed increase in the TNBC and HER2+ groups might also apply to the ER+/HER2- group. In this case, the effect of the increased number of patients with BRCA tests, as shown in Table 1, appears diluted and may be falsely reflected as higher odds for the ER/HER2 unknown group. Despite HER2-positive BC occurring less frequently among BRCA carriers, studies have indicated that patients with this combination have poorer prognoses [32, 33]. Our findings highlight the importance of BRCA testing in patients with other receptor subtypes than TNBC, given its potential impact on treatment decisions and patient outcomes. Even though DBCG guidelines recommend PARPi to selected BRCA-mutated patients who meet the OlympiA trial inclusion criteria, PARPi is not currently approved in Denmark for adjuvant treatment of early BC [34].

Our study is the first to evaluate BRCA test trends in Denmark. A key strength is reporting real-world data on BRCA testing among over 65,000 BC patients from all testing sites during three periods of 6 years each, unlike previous cross-sectional estimates or single-site studies [16, 18, 19]. Furthermore, the high completeness of centralised data, the integration of several Danish registries, and the collaboration of the genetic laboratories to provide updated BRCA results have ensured data robustness. In multivariate LR models with interaction terms, we identified factors that decreased the probability of BRCA testing for patients with unilateral BC, for whom guidelines might be insufficient. The predefined test timing intervals (i.e., BRCA test within 6 months, 6–12 months, 1–2 years and later than 2 years after BC) were based on similar intervals as previously described [18]; however, the DBCG guidelines do not state when the BRCA test should be done. Due to unavailable data, we could not account for patients tested based on pedigree or those who rejected genetic testing. Even though our inclusion period spans over 18 years, our results might not reflect the broadening of the test criteria to all patients younger than 50 at BC and all TNBC patients in 2022. However, extending the inclusion period by an additional 6 years would hinder assessing patients who undergo late testing (more than 2 years after BC).

Conclusion

The rise in BRCA testing of BC patients in Denmark reflects an increased awareness and accessibility due to cheaper NGS testing. Still, test rates increased slower than in other countries, especially for patients older than 40 and for the most common receptor combination, that is, ER-positive/HER2-negative [11, 18]. Current DBCG guidelines recommend BRCA testing for all patients under 50 at BC, while international guidelines recommend testing patients up to age 65, leaving a large gap [8–10]. Implementing mainstreamed genetic testing of patients with surgically treatable BC could eliminate the geographical discrepancy promoting timely detection of BRCA PV and a risk-reducing approach, also beyond young age and TNBC.

Author contribution

AK, AL, MJ, BE, MT, and MR all contributed to the Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Validation, and Writing of the original draft, and all except AK contributed with supervision; AK and MJ conducted the formal analysis; IP, AP, LLC, and KW contributed with data resources, review, and editing of the final draft; AK and AL contributed with funding acquisition; AL was the project administrator of the study.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the board of DBCG, the Capital Region’s Center for Health (R-21061634), and Zealand University Hospital’s Administration Board (EMN-2021-09331). The study is registered at the Capital Region Research Overview – PACTIUS (J.nr. P-2021-0729) and adheres to the General Data Protection Regulations.

Data availability statement

The findings of this study are supported by data which can be provided upon request and approval from the DBCG. Due to institutional restrictions and restrictions by the Danish Health Act, data may not be publicly available.

References

[1] Tung NM, Garber JE. BRCA1/2 testing: therapeutic implications for breast cancer management. Br J Cancer. 2018;119(2):141–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0127-5

[2] Breast Cancer Risk Genes – Association analysis in more than 113,000 women. N Engl J Med. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2021;384(5):428–39. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1913948

[3] Hu C, Hart SN, Gnanaolivu R, Huang H, Lee KY, Na J, et al. A population-based study of genes previously implicated in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):440–51. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2005936

[4] Marmolejo DH, Wong MYZ, Bajalica-Lagercrantz S, Tischkowitz M, Balmaña J, Patócs AB, et al. Overview of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) guidelines across Europe. Eur J Med Genet. 2021;64(12):104350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2021.104350

[5] Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, Phillips K-A, Mooij TM, Roos-Blom M-J, et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for brca1 and brca2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2402–16. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7112

[6] Metcalfe KA, Eisen A, Poll A, Candib A, McCready D, Cil T, et al. Frequency of Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in breast cancer patients with a negative BRCA1 and BRCA2 rapid genetic test result. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(9):4967–73. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-09855-6

[7] DMCG.dk [Internet]. DBCG guidelines for Hereditary Breast Cancer, Dec 2022. Available from: https://www.dmcg.dk/siteassets/kliniske-retningslinjer---skabeloner-og-vejledninger/kliniske-retningslinjer-opdelt-pa-dmcg/dbcg/dbcg_arvelig-cancer-mamma_v.2.0_admgodk_02012023.pdf

[8] Bedrosian I, Somerfield MR, Achatz MI, Boughey JC, Curigliano G, Friedman S, et al. Germline testing in patients with breast cancer: ASCO–Society of Surgical Oncology Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(5):584–604. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.02225

[9] Loibl S, André F, Bachelot T, Barrios CH, Bergh J, Burstein HJ, et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Ann Oncol. 2024;35(2):159–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2023.11.016

[10] Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, Gnant M, Loibl S, Cameron D, Regan MM, et al. Understanding breast cancer complexity to improve patient outcomes: The St Gallen International Consensus Conference for the Primary Therapy of Individuals with Early Breast Cancer 2023. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(11):970–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2023.08.017

[11] Grindedal EM, Jørgensen K, Olsson P, Gravdehaug B, Lurås H, Schlichting E, et al. Mainstreamed genetic testing of breast cancer patients in two hospitals in South Eastern Norway. Fam Cancer. 2020;19(2):133–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-020-00160-x

[12] Grindedal EM, Heramb C, Karsrud I, Ariansen SL, Mæhle L, Undlien DE, et al. Current guidelines for BRCA testing of breast cancer patients are insufficient to detect all mutation carriers. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):438. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3422-2

[13] Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Hughes K, Patel R, Rosen B, Compagnoni G, et al. Underdiagnosis of hereditary breast cancer: are genetic testing guidelines a tool or an obstacle? J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(6):453–60. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01631

[14] Meshkani Z, Aboutorabi A, Moradi N, Langarizadeh M, Motlagh AG. Population or family history based BRCA gene tests of breast cancer? A systematic review of economic evaluations. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2021;19(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-021-00191-0

[15] Rajagopal PS, Catenacci DVT, Olopade OI. The time for mainstreaming germline testing for patients with breast cancer is now. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(24):2177–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00160

[16] Nilsson MP, Winter C, Kristoffersson U, Rehn M, Larsson C, Saal LH, et al. Efficacy versus effectiveness of clinical genetic testing criteria for BRCA1 and BRCA2 hereditary mutations in incident breast cancer. Fam Cancer. 2017;16(2):187–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-016-9953-x

[17] Li J, Wen WX, Eklund M, Kvist A, Eriksson M, Christensen HN, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants in a large, unselected breast cancer cohort. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(5):1195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31841

[18] Kurian AW, Ward KC, Abrahamse P, Bondarenko I, Hamilton AS, Deapen D, et al. Time trends in receipt of germline genetic testing and results for women diagnosed with breast cancer or ovarian cancer, 2012-2019. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15):1631–40. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.02785

[19] Childers CP, Childers KK, Maggard-Gibbons M, Macinko J. National estimates of genetic testing in women with a history of breast or ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3800–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.73.6314

[20] Christiansen P, Ejlertsen B, Jensen M-B, Mouridsen H. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:445–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S99457

[21] Bjerregaard B, Larsen OB. The Danish Pathology Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):72–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810393563

[22] Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–90. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S91125

[23] Gjerstorff ML. The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):42–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810393562

[24] Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S31–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18

[25] Pedersen IS, Schmidt AY, Bertelsen B, Ernst A, Andersen CLT, Kruse T, et al. A Danish national effort of BRCA1/2 variant classification. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(1):159–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2017.1400693

[26] Laugesen K, Ludvigsson JF, Schmidt M, Gissler M, Valdimarsdottir UA, Lunde A, et al. Nordic Health Registry-based research: a review of health care systems and key registries. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:533–54. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S314959

[27] Hooker GW, Clemens KR, Quillin J, Vogel Postula KJ, Summerour P, Nagy R, et al. Cancer genetic counseling and testing in an era of rapid change. J Genet Couns. 2017;26(6):1244–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-017-0099-2

[28] Gronwald J, Cybulski C, Huzarski T, Jakubowska A, Debniak T, Lener M, et al. Genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer in Poland: 1998–2022. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2023;21:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-023-00252-6

[29] Thomassen M, Hansen TVO, Borg Å, Theilmann Lianee H, Wikman F, Søkilde Pedersen I, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Danish families with hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer. Acta Oncol. 2008;47(4):772–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860802004974

[30] DBCG.dk [Internet]. DBCG guidelines for Hereditary Breast Cancer, Sept 2016. Available from: https://dbcg.dk/PDF%20Filer/Kapitel_19_HBOC_23.09.2016.pdf

[31] Mavaddat N, Barrowdale D, Andrulis IL, Domchek SM, Eccles D, Nevanlinna H, et al. Pathology of breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA). Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2012;21(1):134–47. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0775

[32] Tomasello G, Gambini D, Petrelli F, Azzollini J, Arcanà C, Ghidini M, et al. Characterization of the HER2 status in BRCA-mutated breast cancer: a single institutional series and systematic review with pooled analysis. ESMO Open. 2022;7(4):100531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100531

[33] Viansone A, Pellegrino B, Omarini C, Pistelli M, Boggiani D, Sikokis A, et al. Prognostic significance of germline BRCA mutations in patients with HER2-POSITIVE breast cancer. Breast. 2022;65:145–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2022.07.012

[34] Geyer CE, Garber JE, Gelber RD, Yothers G, Taboada M, Ross L, et al. Overall survival in the OlympiA phase III trial of adjuvant olaparib in patients with germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1/2 and high-risk, early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(12):1250–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.09.159