SHORT COMMUNICATION

A PHYSICAL THERAPIST WHO SWEARS: A CASE SERIES

Garrett TRUMMER, DPT, SCS, CSCS, CISSN1, Richard STEPHENS, PhD2 and Nicholas B. WASHMUTH, DPT, DMT, OCS3

From the 1Godspeed, Hoover, AL, United States, 2School of Psychology, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, United Kingdom and 3Department of Physical Therapy, Samford University, Birmingham, AL, United States

Objective: Swearing deserves attention in the physical therapy setting due to its potential positive psychological, physiological, and social effects. The purpose of this case series is to describe 2 cases in which a physical therapist swears in the clinical setting and its effect on therapeutic alliance.

Patients: Case 1 is a 19-year-old male treated for a hamstring strain, and case 2 is a 23-year-old male treated post-operatively for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The physical therapist utilized social swearing in the clinic with the goal of motivating the patient and enhancing the social connection with the patient, to improve therapeutic alliance.

Results: The patient in case 1 reported a decrease in therapeutic alliance after the physical therapist began swearing during physical therapy treatments, whereas the patient in case 2 reported an increase in therapeutic alliance. Both patients disagreed that physical therapist swearing is unprofessional and disagreed that swearing is offensive, and both patients agreed physical therapists should be able to swear around their patients.

Conclusion: Physical therapist swearing may have positive and negative influences in the clinic setting and may not be considered unprofessional. These are, to our knowledge, the first published cases of a physical therapist swearing in the clinical setting.

LAY ABSTRACT

Swearing produces positive effects that cannot be achieved with any other forms of language. Quite simply, swearing is powerful and deserves attention in the physical therapy setting. Swearing can lead to tighter human bonds, thereby enhancing the social connection between a patient and a physical therapist. This case series describes 2 cases where a physical therapist swears with patients in the clinical setting and its effect on their social connection. While swearing increased the social connection in 1 case, it decreased it in the other case. None of the patients thought that physical therapist swearing was unprofessional, and both patients believe physical therapists should be able to swear around their patients. The results of these cases indicate that physical therapist swearing can have positive and negative influences in the clinic. More studies are needed to help determine when, how, and if to swear in the physical therapy setting.

Key words: physical therapy; swearing; therapeutic alliance; professionalism; communication

Citation: JRM-CC 2023; 6: jrmcc10277. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/jrmcc.v6.10277

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Mar 24, 2023; Published: Apr 27, 2023

Correspondence address: Nicholas B. Washmuth, Department of Physical Therapy, Samford University, 800 Lakeshore Drive, Birmingham, AL 35229, United States. E-mail: nwashmut@samford.edu

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

No funding is affiliated with this project.

Words have the ability to change the way a person thinks, feels, and performs. In a clinical setting, the words used by physical therapists (PTs) can impact social, psychological, and biological factors and have the capacity to either heal or cause harm (1, 2). Swearing, or uttering a word that is considered taboo, is an often-ignored part of our language due to the controversial nature of the topic and the potential negative consequences of swearing. Swearing can be considered as unprofessional, since it is considered taboo, usually judged as shocking, and the swearer may be considered antisocial, offensive, incompetent, and untrustworthy (3–5). However, arguments have been made that professionalism creates a distance between the healthcare provider and the patient that interferes with their relationship (6). Swearing within the context-specific relationship between a PT and a patient may actually enhance their professional relationship (7, 8), since language is the basis of the therapeutic relationship (9). Therefore, PTs need guidance regarding the use of swearing within the context of a therapeutic relationship.

Swearing can be perceived as an extreme insult, thereby harming the therapeutic relationship, and swearing can constitute harassment, leading to legal repercussions (10, 11). It is poorly understood when, how and if PTs should swear with patients. However, humans have been swearing since the emergence of language (7), and it is quite common, with evidence suggesting 58% of the population swear “sometimes” or “often” and less than 10% of the population report “never” or “rarely” swearing (3). Since swearing produces a range of distinct positive psychological, physiological, and social outcomes and generates effects that are not observed with other forms of language (12), it would seem like the ideal language for building and maintaining positive therapeutic relationships between PTs and their patients (13).

The positive social connection between the patient and PT, known as the therapeutic alliance, has a direct effect on treatment outcomes (14–16). Communication styles that help clinicians engage with patients have been shown to correlate with therapeutic alliance (17). Swearing can lead to tighter human bonds and create informal environments where people are more likely to be themselves (7), which may enhance the therapeutic alliance. Swearing has been shown to help build rapport (8) and can be used to manifest solidarity (18). Social groups depend on a shared willingness to participate in risks, swearing being one of them. Therefore, swearing may help create a “we’re-all-in-this-together” culture and can be used as a tactic to create tighter human bonds.

In mental health settings, Giffin (19) had 50 patients complete an anonymous online survey, and the data collected showed significant client support for the use of swearing by the therapist. A majority of patients reported that they felt an improved sense of rapport when their therapist swore, as 92% of patients reported that therapists should be able to swear around their clients, 80% reported that their therapist’s use of swear words helped their therapeutic relationship, and over 88% of patients described an explicitly positive experience with therapist swearing (19). It is also important to note that none of the patients felt that swearing hurt their therapeutic relationship (19).

It is important to understand the context and the impact that PT swearing has on therapeutic alliance. This understanding will help PTs know when, how, and if to swear with their patients. The purpose of this case series is to describe 2 cases where a 32-year-old male Caucasian PT swore in the clinical setting and its effect on therapeutic alliance.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

An informed consent was obtained for each patient. Each patient received a standard examination by a licensed PT, which included postural assessment, joint range of motion (ROM) measurements, manual muscle testing, palpation, gait assessment, joint mobility testing, special tests, and neurological screening.

Case 1: 19-year-old male, hamstring strain

A 19-year-old male Caucasian collegiate baseball player was referred to physical therapy for a right hamstring strain. He was otherwise healthy with no outstanding past medical history. This hamstring strain occurred during offseason strength and conditioning, when the patient was running sprints and felt a “pop”. He described his right posterior thigh pain as “sharp” and “achy”. Pain increased with right lower extremity movements, affecting his ability to participate in baseball and strength and conditioning activities. Patient’s goals were to reduce his posterior thigh pain and return to his baseball and training activities.

Physical examination was unremarkable, except for strength deficits and pain with resistance testing of right hip extension and knee flexion, tender to palpation of right hamstring muscle belly, and pain and decreased extensibility during straight leg raise hamstring length test. Clinical examination suggested patient sustained a grade 1 hamstring strain (20). Patient was treated with standard of care, including eccentric training, stretching, strengthening, stabilization, progressive running and agility training, and trunk stabilization (20).

Patient was seen for 7 visits over 3.5 weeks. At discharge, patient was able to return to baseball and strength and conditioning activities without hamstring discomfort.

Case 2: 23-year-old male, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

A 23-year-old male Indian medical student was referred to physical therapy after tearing his right anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) while playing flag football and undergoing subsequent ACL reconstruction surgery. Clinical examination was consistent with status post ACL reconstruction. The patient was treated with standard of care after an ACL reconstruction, including weight bearing as tolerated, gait training, interventions to decrease pain and effusion, cryotherapy, electrostimulation for muscle reeducation, quadriceps and lower extremity strengthening, and neuromuscular training (21, 22).

Patient was seen for 8 visits over 3.5 weeks. Patient initiated physical therapy in his hometown while on his winter break from medical school. After 8 visits of physical therapy, patient returned to medical school and transferred to a physical therapy clinic more convenient to his medical school campus.

SWEARING STRATEGIES

Social swearing, as opposed to annoyance swearing, serves interpersonal functions, such as group bonding and impression management and is seen as positively charged (12). The PT utilized social swearing during treatment sessions with the goal of motivating the patients and enhancing the social connection with the patients, to improve therapeutic alliance. It is important to note that the social swearing implemented by the PT did not include weaponized use of taboo language to inflict or subject the patients to demeaning emotional insult or harassment.

The PT began to swear during the 3rd physical therapy visit for both patient cases and swore 2–3 times each visit thereafter. Swearing was initiated on the 3rd visit to ensure rapport between the patient, and PT was established, with swearing being utilized to further improve their relationship and therapeutic alliance. Each episode of swearing by the PTs was attempted to be well-timed for the purpose of motivation and solidarity. For example, during case 1, the PT said, “Hell yes bro, that is good s***! Keep up the f***ing good work!”, while the patient was performing a challenging exercise. The patient smiled and proceeded to say, “F*** yeah dude, let’s f***ing go!” and then continued performing his exercises. An example during case 2, the PTs said, “Dude, if you continue to work your f***ing a** off like this, you will become a f***ing animal!” during a treatment session. The patient started laughing immediately and said, “You’re damn right.” and continued to work through his exercises.

SWEARING OUTCOMES

The Helping Alliance Questionnaire (HAQ), a self-reported outcome measure that is completed by both the patient and the PT, was used to monitor the therapeutic alliance at 2 points during the episodes of care of these patients to help show the evolution of the therapeutic alliance and swearing over time.

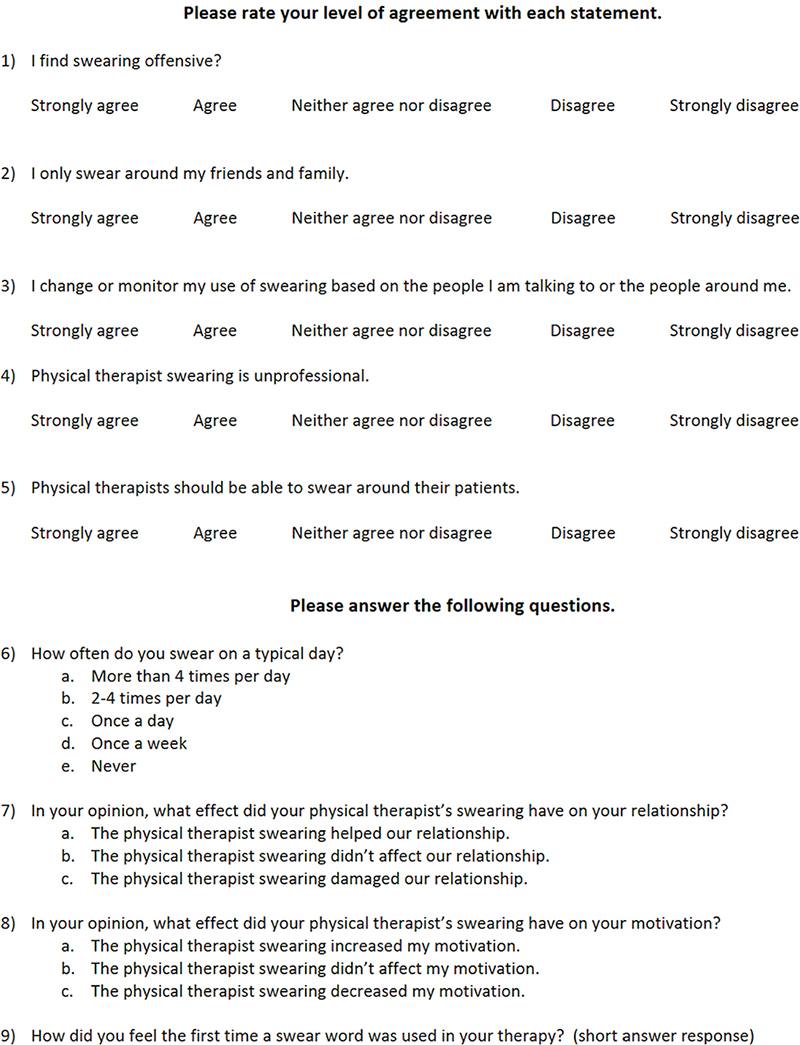

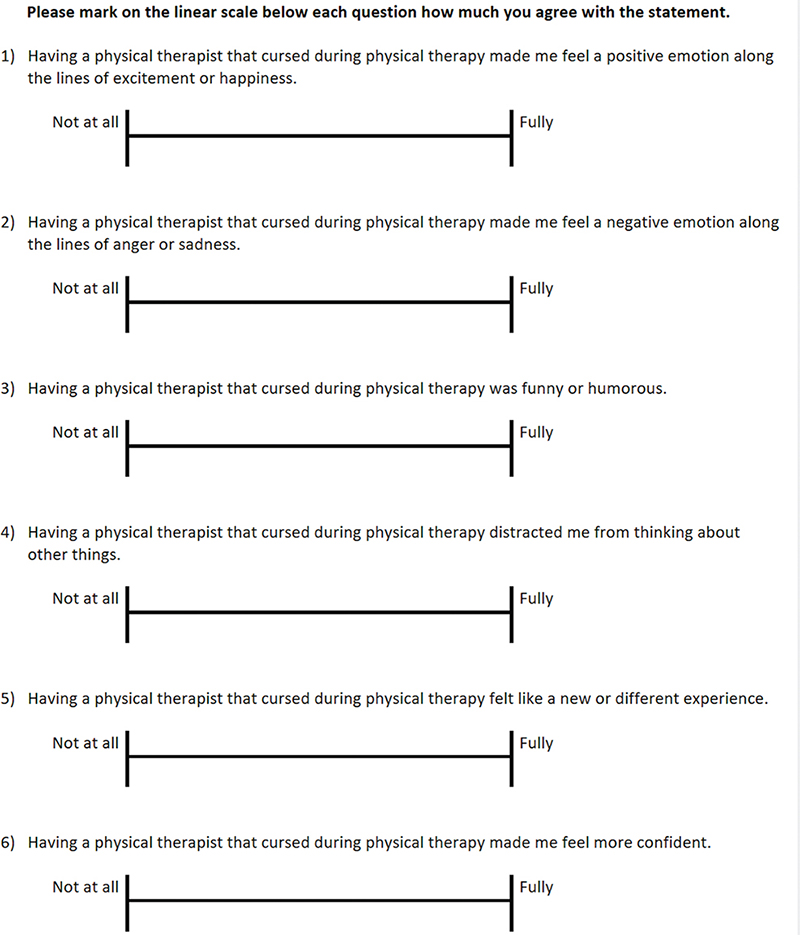

An additional swearing survey was developed by the researchers, based on the works of Giffin (19) and Stephens et al. (23), to better understand the context in which swearing occurred. The swearing survey was completed at discharge and included questions about the patients’ general opinions of swearing, thoughts on the professionalism and acceptability of swearing in physical therapy, and how swearing effected the patient–PT relationship, and also included questions based on the possible psychological mechanisms by which swearing fulfills positive functions. This swearing survey is presented in Fig. 1. Summaries of the therapeutic alliance and swearing survey outcomes are presented in Tables I and II, respectively.

Fig. 1. Researcher developed swearing survey.

Case 1: 19-year-old male, hamstring strain

During the 4th visit, the patient and PT completed the HAQ. At discharge, the patient and PT completed the HAQ again (7th visit). At the 4th visit, the patient scored 94/114 on the HAQ and the PT scored 92/114 (19 = poor therapeutic alliance and 114 = strong therapeutic alliance). At discharge, the patient scored 89/114 on the HAQ, and the PT scored 98/114. These results suggest that the patient’s self-reported therapeutic alliance score decreased (94/114 to 89/114) as the PT swore during treatment sessions, while the PT’s self-reported therapeutic alliance increased (92/114 to 98/114).

The patient completed the researcher-developed swearing survey at discharge. The patient disagreed with the following statements: “I find swearing offensive,” “I only swear around my friends and family,” and “PT swearing is unprofessional.” The patient agreed with the following statements: “I change or monitor my use of swearing based on the people I am talking to or the people around me” and “PTs should be able to swear around their patients.” The patient swears more than 4 times per day and believed that the PT swearing did not affect their relationship or his motivation. When asked “How did you feel the first time a swear word was used in your therapy?” the patient responded, “It didn’t bother me at all. I am used to it.”

Based on the possible psychological mechanisms by which swearing fulfils positive functions, the most noted effect on this patient was that the PT swearing was funny or humorous. All other mechanisms were scored at 50% or less agreement from the patient. Specific swearing survey results are listing in Table II.

Case 2: 23-year-old male, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

Similar to case 1, the patient and PT completed the HAQ during the 4th visit and again at discharge (8th visit). At the 4th visit, the patient scored 110/114 on the HAQ, and the PT scored 100/114 (19 = poor therapeutic alliance and 114 = strong therapeutic alliance). At discharge, the patient scored 113/114 on the HAQ, and the PT scored 110/114, suggesting that both the patient’s and PT’s self-reported therapeutic alliance scores increased (patient 110/114 to 113/114; PT 100/114 to 110/114) as the PT swore during treatment sessions.

At discharge, the patient strongly disagreed with “I find swearing offensive” and “PT swearing is unprofessional” and agreed with “I only swear around my friends and family” and “PTs should be able to swear around their patient.” Patient neither agreed nor disagreed with “I change or monitor my use of swearing based on the people I am talking to or the people around me.” The patient reported swearing more than 4 times per day and believed that the PT swearing helped their relationship and increased his motivation. When asked “How did you feel the first time a swear word was used in your therapy?” the patient responded, “Increased the mood in they gym.”

The patient fully agreed that the PT swearing made him feel a positive emotion, was funny or humorous, distracted him from thinking about other things, felt like a new or different experience, and made him feel more confident. The patient did not agree at all that the PT swearing made him feel a negative emotion.

DISCUSSION

Swearing produces psychological, physiological, and social effects that are not achieved by other forms of language; simply stated, swearing is powerful (12). This case series describes the use of swearing by a PT in the clinical setting with the primary goal of improving the therapeutic alliance. As the PT swore during physical therapy sessions, the patient in case 1 reported a decrease in therapeutic alliance, while the patient in case 2 reported an increase in therapeutic alliance. The PT reported an increase in therapeutic alliance in both case 1 and case 2. Although the decreases and increases in therapeutic alliance in these cases were small, there was a decrease in the patient reported therapeutic alliance in 1 case, and an increase in the other case.

Some view swearing as unprofessional and offensive, yet patients in both cases disagreed that PT swearing is unprofessional and disagreed or strongly disagreed that they find swearing offensive. Both patients agreed that PTs should be able to swear around their patients. This is consistent with mental health settings, where Giffin (19) surveyed 50 patients, and 92% reported that mental health therapists should be able to swearing around their clients. Neither patient in these cases reported that the PT swearing damaged their relationship, consistent with the study by Giffin (19), where none of the mental health patients felt that the use of swearing words hurt the therapeutic alliance with their therapist.

The cause-and-effect relationship between therapeutic alliance and patients’ compliance cannot be determined in a case series; however, both patients had a 100% arrival rate to their scheduled physical therapy appointments and voiced being compliant with the home exercise program (HEP) prescribed by the PT. The PT also observed that both patients routinely arrived early to their treatment sessions, ranging from 2 to 20 min early. Compliance with a physical therapy plan of care and adhering to a HEP can impact treatment outcome (24, 25). The average physical therapy patient no-show rate in the United States is as high as 14.5% with the most commonly reported reason for a no-show being that the patient “forgot” (26). A good therapeutic alliance is believed to improve patient compliance with a physical therapy plan of care (27). Additional research is needed to determine the effects PT swearing has on arrival rates and HEP compliance.

The patients in both cases were young adults (19-years-old and 23-years-old) and male, with 1 patient being Caucasian and the other being Indian. The PT was also relatively young (32-years-old), male, and Caucasian. The outcomes of the physical therapist (PT) swearing may change with different age, gender, religion, social status, geographic location, cultural background, and race dynamics between the PT and patients (3). In the mental health setting, swearing is viewed differently depending on the gender of the counselor, as a female client views a male therapist swearing as less favorable than swearing by a female therapist (28). Race can also change how the swearer is interpreted. Swearers of color are judged more harshly for their language compared to Caucasians (3). The specific effects swearing had on the patients in these cases are highly context-dependent, and the outcomes of the PT swearing in these cases may have changed with different age, gender, social status, geographic location, cultural background, or race dynamics. “F**”, “s***”, and “a**” are frequently used and accepted words in daily conversation in the United States; however, these swear words may not have the same effect in other geographic regions or cultures (3). A PT should select swear words appropriate to their region and culture. Although swearing can be used to express positive and negative emotions, it was the goal of the PT to incorporate social swearing in a positive connotation to intensify the expression of positive emotion and encouragement, to enhance the therapeutic relationship.

This case series has multiple limitations. Many factors contribute to the therapeutic alliance, including agreement on treatment goals, agreement on tasks, and the personal bond between the patient and PT (29). The therapeutic alliance in these cases may be a product of other factors, and swearing did not impact the personal bond between the patient and PT. Nevertheless, one of the patients believed that the PT swearing helped their relationship, increased motivation, and increased the mood in the gym, while the other patient believed that swearing did not affect the patient–PT relationship or motivation. Therefore, PT swearing may have positively impacted 1 patient and had no effect on the other patient. The HAQ is a reliable and valid self-reported measure of the therapeutic alliance (30); however, the HAQ was developed for psychoanalysts (14) and may lack specificity in the field of physical therapy. The swearing survey used in this study asked the patients about their general opinions of swearing; however, asking patients about swearing without contextual information may minimize the insight in their opinions of swearing in therapeutic contexts, making the swearing survey invalid. The results of case series cannot be generalized to other patients. Additional research is needed to determine the positive and negative effects of PT swearing in the physical therapy setting, and to help determine when, how, and if PT should swear.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PHYSICAL THERAPISTS

This case series serves to inform PTs about the use of swearing with patients and what effects swearing might have on the therapeutic alliance. It is likely not possible for PTs to swear indiscriminately with all patients in all settings, as swearing can have both positive and negative effects. At this time, it is challenging to justify PT swearing, due to the lack of information on the subject. PT swearing may be risky since not everyone prefers that type of language, highlighting the need for future studies to help determine when, how, and if to swear in the physical therapy setting.

The notion that swearing may add value to physical therapy clinical practice remains underrepresented in the literature. Swearing is prevalent in public discourse and mass media in American society (31). More than 70% of adults reported frequently or occasionally hearing individuals swear in public (32), and 57% of workers swear in the workplace (28), suggesting that swearing is a common part of everyday speech, even in more formal settings. Despite the prevalence of swearing, there is little research on the topic in the physical therapy field.

CONCLUSIONS

This case series describes the use of swearing by a PT in the clinical setting and its effect on the therapeutic alliance. The results of these cases indicate that PT swearing, although taboo, may have both positive and negative influences in the clinic and may not be consider unprofessional. These are, to our knowledge, the first published cases of a PT swearing in the clinical setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Godspeed for allowing our research team to utilize their clinic and resources for the purpose of this project. Without their generosity, this article would not have been possible.

REFERENCES

- Stewart M, Loftus S. Sticks and stones: the impact of language in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2018; 48: 519–522. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2018.0610

- Puentedura EJ, Louw A. A neuroscience approach to managing athletes with low back pain. Phys Ther Sport 2012; 13: 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2011.12.001

- Beers Fägersten K. Who’s swearing now? The social aspects of conversational swearing. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2012.

- Cavazza N, Guidetti M. Swearing in political discourse: why vulgarity works. J Lang Soc Psychol 2014; 33: 537–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X14533198

- Johnson DI, Lewis N. Perceptions of swearing in the work setting: an expectancy violations theory perspective. Commun Rep 2010; 23: 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2010.511401

- Green R, Gregory R, Mason R. Professional distance and social work: stretching the elastic? Aust Soc Work 2007; 59: 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070600986010

- Vingerhoets AJJM, Bylsma LM, de Vlam C. Swearing: a biopsychosocial perspective. Psych Top 2013; 22: 287–304.

- McLeod L. Swearing in the “tradie” environment as a tool for solidarity. Griffith Work Pap Pragmat Intercult Commun 2011; 4: 1–10.

- Wachtel PL. Therapeutic communication: knowing what to say when. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2011.

- DuFrene DD, Lehman CM. Persuasive appeal for clean language. Bus Commun Q 2002; 65: 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/108056990206500105

- Wah L. Profanity in the workplace. Manage Rev 1999; 88: 8.

- Stapleton K, Beers Fägersten K, Stephens R, Loveday C. The power of swearing: what we know and what we don’t. Lingua 2022; 277: 103406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2022.103406

- Washmuth NB, Stephens R. Frankly, we do give a damn: improving patient outcomes with swearing. Arch Physiother 2022; 12: 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40945-022-00131-8

- Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther 2010; 90: 1099–1110. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20090245

- Kinney M, Seider J, Beaty AF, Coughlin K, Dyal M, Clewley D. The impact of therapeutic alliance in physical therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract 2018; 36: 886–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1516015

- Fuentes J, Armijio-Olivo S, Funabashi M, Miciak M, Dick B, Warren S, et al. Enhanced therapeutic alliance modulates pain intensity and muscle pain sensitivity in patients with chronic low back pain: an experimental controlled study. Phys Ther 2014; 9: 477–789. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130118.cx

- Pinto RZ, Ferreira ML, Oliveira VC, Franco MR, Adams R, Maher CG, et al. Patient-centred communication is associated with positive therapeutic alliance: a systematic review. J Physiother 2012; 58: 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70087-5

- Baruch Y, Jenkins S. Swearing at work and permissive leadership culture: when anti-social becomes social and incivility is acceptable. Leadersh Organ Dev J 2007; 28: 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730710780958

- Giffin HJ. Client’s experiences and perceptions of the therapist’s use of swear words and the resulting impact on the therapeutic alliance in the context of the therapeutic relationship. Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2016. [cited 2022 December 28] Available from: http://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1696

- Martin RL, Cibulka MT, Bolgla LA, Koc TA, Loudon JK, Manske RC, et al. Hamstring strain injury in athletes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2022; 52: CPG1–44. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2022.0301

- Andrade R, Pereira R, van Cingel R, Staal JB, Espregueira-Mendes J. How should clinicians rehabilitate patients after ACL reconstruction? A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) with focus on quality appraisal (AGREE II). Br J Sports Med 2020; 54: 512–519. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100310

- van Melick N, van Cingel REH, Brooijmans F, Neeter C, van Tienen T, Hullegie W, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50: 1506–1515. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095898

- Stephens R, Dowber H, Barrie A, Almeida S, Atkins K. Effect of swearing on strength: disinhibition as a potential mediator. Q J Exp Psychol 2022; 76. https://doi.org/10.1177/17470218221082657

- Mbada CE, Nonvignon J, Ajayi O, Dada OO, Awotidebe TO, Johnson OE, et al. Impact of missed appointments for outpatient physiotherapy on cost, efficiency, and patients’ recovery. Hong Kong Physiother J 2013; 31: 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hkpj.2012.12.001

- Peek K, Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, Mackenzie L. Physiotherapists’ perceptions of patient adherence to prescribed self-management strategies: a cross-sectional survey of Australian physiotherapists. Disabil Rehabil 2017; 39: 1932–1938. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1212281

- Bokinskie J, Johnson P, Mahoney T. Patient no-show for outpatient physical therapy: a national survey. UNLV Theses Dissertations Prof Pap Capstones; 2015, Las Vegas.

- Room J, Boulton M, Dawes H, Archer K, Barker K. Physiotherapists’ perceptions of how patient adherence and non-adherence to recommended exercise for musculoskeletal conditions affects their practice: a qualitative study. Physiotherapy 2021; 113: 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2021.06.001

- Williams IL, Uebel M. On the use of profane language in psychotherapy and counseling: a brief summary of studies over the last six decades. Eur J Psychother Couns 2021; 23: 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2021.2001025

- Babatunde F, MacDermid J, MacIntyre N. Characteristics of therapeutic alliance in musculoskeletal physiotherapy and occupational therapy practice: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17: 375. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2311-3

- Luborsky L, Barber JP, Siqueland L, Johnson S, Najavits LM, Frank A, et al. The revised helping alliance questionnaire: psychometric properties. J Psychother Pract Res 1996; 5: 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07504-000

- Jay T. The utility and ubiquity of taboo words. Perspect Psychol Sci 2009; 4: 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01115.x

- The associated press profanity study. Ipsos Public Affairs [Internet]. 2006; Available from: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/news_and_polls/2006-03/mr060328-2.pdf