Original Report

LONG-STANDING COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME-TYPE I: PERSPECTIVES OF PATIENTS NOT AMPUTATED

Patrick N. DOMERCHIE, MD1, Pieter U. DIJKSTRA, PhD1,2, Jan H.B. GEERTZEN, MD, PhD1

From the 1University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2Sirindhorn School of Prosthetics and Orthotics, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Objective: Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type I (CRPS-I) is an often intractable regional pain syndrome, usually affecting limbs in which amputation may be a final resort. Not all patients are suited for amputation.

This retrospective case series with explorative interviews aims to gain insight in the quality of life in those who have been denied an amputation and their functioning with CRPS-I.

Patients and methods: Between 2011 and 2017, 37 patients were denied an amputation. Participants were interviewed regarding quality of life, treatments received since their outpatient clinic visit and their experiences at our outpatient clinic.

Results: A total of 13 patients participated. Most patients reported improvements in pain, mobility and overall situation. All patients received treatments after being denied an amputation, with some reporting good results. Many felt they had no part in decision making. Of the 13 participants 9 still had an amputation wish. Our participants scored worse in numerous aspects of their lives compared with patients with an amputation from a previous CRPS-I study of us.

Conclusion: This study shows that amputation should only be considered after all treatments have been tried and failed, since most participants reported improvements in aspects of their functioning over time.

LAY ABSTRACT

People with complex regional pain syndrome suffer from severe pains, usually in a limb, which can lead to serious and longstanding disability. Sometimes when all other treatments have been tried, amputation is the only option left. Not all patients are suitable for amputation. This study tries to gain insight into those patients who have been denied an amputation. Our findings show that over time most patients reported improvements in pain, mobility and overall situation. All patients received further treatments after being denied amputation. Our study showed that amputation should only be considered after all other treatments have been tried and have failed, since over time, most of our participants still reported improvements in various aspects of their functioning.

Key words: amputation; CRPS-I; pain; QoL.

Citation: JRM-CC 2023; 6: jrmcc7789. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/jrmcc.v6.7789

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: 12 April 2023; Published: May 25, 2023

Correspondence address: Patrick N. Domerchie, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Internal postal code CB40, PO box 30.001, 9700 RB Groningen, the Netherlands. Tel: +31 50 36 18506. E-mail: p.n.domerchie@umcg.nl

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type I (CRPS-I) is a syndrome of unknown pathophysiology with severe regional pain and autonomic dysregulation, usually in limbs, developing after (minor) trauma, surgery or sometimes spontaneously (1–4). The CRPS-I is diagnosed using the Budapest criteria as a diagnosis of exclusion (5,6). Treatment options include medication, neuromodulation, mirror therapy, physical therapy and rehabilitation programs (1,6–12). The CRPS-I that does not improve following different treatments is considered therapy resistant (1,13). Long-standing therapy-resistant CRPS-I (> 1 year) may impact greatly on patients’ life, for example, pain, inability to use affected limbs, loss of work and social contacts because of disability, lack of sleep and loss of intimacy (14–16).

Amputation is considered a last treatment option for long-standing therapy-resistant CRPS-I, but is controversial because it is irreversible with different success rates (17,18). Apart from the general perioperative complications such as blood loss and infection, phantom limb pain or recurrence of CRPS-I in the residual limb may develop (17,18). Amputations seem to be more successful in patients with high resilience, realistic expectations regarding living with amputations, and without psychological/psychiatric histories (19).

When patients are referred to our outpatient clinic with amputation wishes, they often put all their hopes in an amputation. Given the irreversibility of this treatment, patients are put through assessments by a physical therapist, psychologist, pain specialist, surgeon and a rehabilitation physician to assure that amputation has a substantial chance of being beneficial (19,20). Another essential prerequisite is that all other treatment options have been tried before even considering amputation, as recommended in both Dutch and English evidence-based guidelines (11,12). Overall, our results show that amputation-eligible patients have a better quality of life (QoL) after their amputation and would choose amputation again (21). Furthermore, our previous study regarding patients who did receive an amputation, conducted similar to this study, showed improvements in mobility and reduction of pain (18). However some patients who were amputated experienced deteriorations in intimacy, self-confidence, sleep and household activities (21,22).

Reasons for denying patients amputation include not having tried all treatment options, psychological or psychiatric comorbidities, somatic contraindications or comorbidities and unrealistic expectations of amputation. In our outpatient clinic, 37% of patients are denied an amputation (18).

It is unclear what happens with patients who were denied amputations. Clinically patients were angry, disappointed and (very) emotional after being told that amputation was no option. Studies regarding patients with therapy-resistant CRPS-I who were denied amputations are not available.

The aim of this study, therefore, is to gain an insight into QoL, pain, functioning and course of long-standing CRPS-I in patients who were denied amputations. In addition, we explored the experience these patients had when visiting our outpatient clinic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Between 2011 and 2017, 37 patients were denied amputations by a specialized CRPS-I team. These patients had been referred by their own physician after expressing an amputation wish because of pain and/or inability to use their limb despite having tried other treatments. The physical assessment took place over the course of one day (21,23).

Procedures

All 37 patients received invitation letters for this explorative interview study. They could send their informed consent forms back in prepaid envelopes. After obtaining informed consent, participants were scheduled for the interviews, by a physician (P.N.D.), who has no (therapeutic) relationship with these patients.

Semi-structured interviews

The telephone interview consisted of 32 questions (and sub-questions) and the depression part (7 statements) of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire (HADS-D) (24,25). The first 19 questions compared current functioning with that of their consultation in the past. These statements concerned mobility, work, social life, sleep, pain, intimacy, self-care, self-confidence and appearance and were rated on 5 point Likert scales (important or small deterioration, no change, small or important improvement). Participants were encouraged to elaborate on answers. Pain-related questions included: 11 point numeric rating scale (NRS; 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst imaginable pain), type of pain and whether or not they believed to still have CRPS-I. Two questions assessed employment and education.

The HADS-Depression subscale consists of 7 statements with 4 point rating scales. At a sum score > 8, the HADS-Depression has a sensitivity and specificity of 0.70–0.90 (25). This first part of the interview was chosen because it had been used in previous research regarding patients with therapy-resistant CRPS-I who had received amputations. The final 9 questions concerned the wish for amputation now and at the time of their first consultation and how participants had experienced the specialized CRPS-I team, what treatment(s) they had received after being denied amputation, and the effect these treatments had on functioning. Lastly, participants were asked to reflect on a patient who underwent amputation but had a recurrence of CRPS-I and was now giving lectures that amputation is not an option for long-standing therapy-resistant CRPS-I (22).

All interviews were recorded, anonymized and transcribed in Microsoft Word (P.N.D). All participants were offered the opportunity of receiving copies of the transcription at the end of the interviews to provide feedback.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS (IBM, version 23). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Characteristics were compared between participants and non-participants. Chi-Square tests were used for nominal data and Mann–Whitney U tests for time-related data.

Percentages and absolute numbers were used to report outcomes of the interviews and participants’ characteristics, accompanied with quotes to put data in context. Finally, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to describe changes in pain between their first consultation and the interview. Similarly, employment and education status at time of visit and the interview were analyzed using McNemar’s test.

Ethical approval

The study proposal was discussed with the Medical Ethics Committee and, since it is not clinical research as described in the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO), we did not need formal approval by the METc and received a waiver (Ref no: 2018/484).

RESULTS

Comparing in- and exclusions

Of the 37 eligible participants, 10 participants never responded, 12 refused to participate. One participant could not be reached after scheduling the interview and 1 participant was excluded because her general practitioner was afraid that the interview might cause a relapse of suicidal tendencies. Thirteen patients (35%) agreed to participate.

No significant differences were found between participants and non-participants (Table I).

| Patient characteristics | Participants (n = 13) | Non-participants (n = 24) | p-value |

| MWU test | |||

| Age at the time of diagnosisa | 36.0 (25.1; 45.9) | 39.5 (20.4; 47.1) | 0.940 |

| Age at the time of visiting the outpatient clinica | 49.3 (34.6; 57.9) | 43.8 (36.6; 50.6) | 0.548 |

| Time between diagnosis and first visita | 7.4 (5.2; 13.8) | 4.9 (2.8; 8.4) | 0.209 |

| Time between first visit and interviewa | 4.2 (2.4; 8.1) | NA | NA Chi squared test |

| Sex (M/F)b | 5/8 | 7/17 | 0.716 |

| CRPS-I in one or multiple extremities (One/Multiple)b | 7/6 | 13/6 | 0.473 |

| CRPS-I in upper extremities (Yes/No)b | 7/6 | 5/14 | 0.150 |

| CRPS-I in lower extremities (Yes/No)b | 10/3 | 18/1 | 0.279 |

| Wish for amputation of upper or lower extremities (upper/lower)b | 4/9 | 1/18 | 0.132 |

| a In years, median, (Q1: Q3). | |||

| b Absolute numbers. Not all data were available for non-participants. | |||

| MWU test: Mann–Whitney U test; NA: Not applicable; CRPS-I Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type I. | |||

Characteristics of included participants

The male/female ratio was 5/8 (n = 13). Nine participants requested amputations of a leg and 4 participants requested amputations of an arm. Some participants reported CRPS-I in other limbs as well, albeit not as debilitating/impacting that they requested amputations.

Basic information regarding the interview

The median duration of the interviews was 53 min (Q1: 39 min; Q3: 01 h: 03 min). The median time between first visit and interview was 4.2 years (Q1: 2.4 years; Q3: 8.1 years).

Other treatments

All interviewed participants received treatments after their first visit. Most participants received pain medication (n = 10) and/or pain rehabilitation (n = 11), and a considerable number received neurostimulation (spinal cord) (n = 5) or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (n = 4). Neurostimulation was generally experienced as having a positive effect:

I sleep a lot better, because my neurostimulator is on during the night as well, it’s always on. Now I sleep a lot better. Five years ago I slept 2–3 hours total per night, and now I tend to sleep the entire night. (m, 36 yrs)

Three participants were amputated in another clinic after visiting our clinic, for a variety of reasons (infection, contracture and a severe joint inflammation).

Questions regarding daily life

Between first visit and the interview, some participants experienced great fluctuations in pain intensity, others reported improvements or deterioration of pain intensity (Table II).

Generally, mobility improved or stayed the same, while toilet use and standard activities of daily living (ADL) deteriorated. The same was found for household activities, with the majority either experiencing no change (n = 4) or some deterioration (n = 6) (Table II).

Remaining ADL independent was very important for participants:

I just wear incontinence material so I do not have to call for help to get me to the toilet quickly. (f, 73 yrs)

Improvements of one item did not necessarily mean improvements other items:

There is a definite improvement since I no longer feel that pain, though there is no improvement in tying my shoelaces or putting my pants on. (m, 51 yrs)

Most participants reported no change in (voluntary) work (n = 7) or sports activities (n = 6) because they were already occupationally disabled, whereas pursuing hobbies had an equal number of participants reporting improvements or deteriorations.

A majority of participants stated that CRPS-I had negative effects on social contacts, intimacy, mood and feeling understood, with some items being more consistent and others deteriorating over time.

Participants furthermore reported that CRPS-I negatively affected perception of appearance, with the majority either noticing no change (n = 6) or a deterioration (n = 5).

One participant stated that she didn’t see her CRPS-I affected limb as her own anymore:

It’s like a lump of meat that I have to drag along. (f, 39 yrs)

Some participants experienced quitting pain medication as an improvement, while others experienced taking more pain medication (reducing the pain) as an improvement.

When asked about the overall change over time, most participants either reported an important improvement (n = 5) or an important deterioration (n = 4). All participants who reported overall improvement had received effective treatment for their CRPS-I after being denied amputation, such as a neurostimulator, or pain rehabilitation and learning to accept the pain:

I enjoy life more now, compared to my visit to your outpatient clinic. Simply because I could give it (CRPS-I) a place instead of making it a leading role of my life story. (f, 47 yrs)

Changes in pain and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type I

Overall participants reported less pain over time; median reduction in pain was 2 points on a NRS scale (Q1: 0.0; Q3: 4.0, p = 0.018). Eight participants were certain they still had CRPS-I. Two reported they no longer had CRPS-I and 4 were uncertain if they ever had CRPS-I in the first place.

Questions regarding work and education

No differences were seen in employment rate, number of participants volunteering or receiving education. Most participants were already declared occupationally disabled and were not receiving education at the time of the first visit (McNemar’s test: p > 0.99).

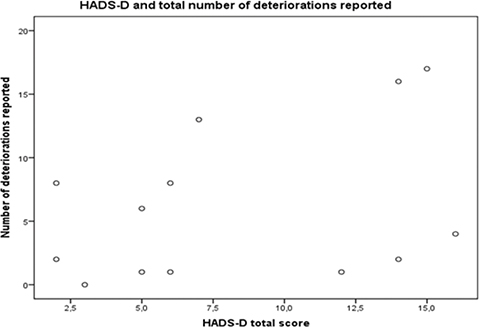

HADS-D questionnaire

The median HADS-D score was 6 (Q1: 5: Q3: 14), five participants scored > 8 points. No association was found between HADS-D scores and total number of deteriorations in daily life (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Correlation between deteriorations reported and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire Score.

Y-axis: total number of deteriorations (small and important deteriorations) per participant.

X-axis: HADS-D total score per participant.

Spearman’s Rho: 0.362 p = 0.224.

Regarding the first visit

Nine participants still had active amputation wishes because of pain and limitations in movement. One participant stated that an amputation would improve his social life, because he could then join a sport club.

Most participants felt like they had no part in the decision whether or not to amputate (n = 8).

On average participants rated their satisfaction with the amputation team a 6.9 (scale 0–10). When asked about shared decision making, mixed reactions were given, with some participants feeling part of the team and other participants feeling the opposite.

When participants were asked to reflect on the patient lecturing that amputation is never an option, some participants agreed and some disagreed.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective case series with explorative interviews showed that over time, some patients with long-standing CRPS-I who were denied amputations, still report improvements in aspects of their life. The reasons for these improvements vary greatly; effective treatments were found, or learning to cope better. Particularly those who remained mobile or found new hobbies reported improvements.

These results confirm previous findings in CRPS-I patients who showed that QoL in CRPS-I was more negatively impacted by disabilities related to CRPS-I (such as immobility or inability to engage in hobbies), than the amount of perceived pain (14). Although participants had improved on many aspects of their lives, a majority still had an active amputation wish, mostly due to physical disabilities or pain.

Some aspects such as work and education, did not change much over time, probably because patients were referred to our outpatient clinic after having suffered from CRPS-I for a long time. By then they had already developed disabilities and thus were often unable to work. The high amount of work incapacitated people in our study is in line with previous studies regarding unemployment due to CRPS-I (26,27).

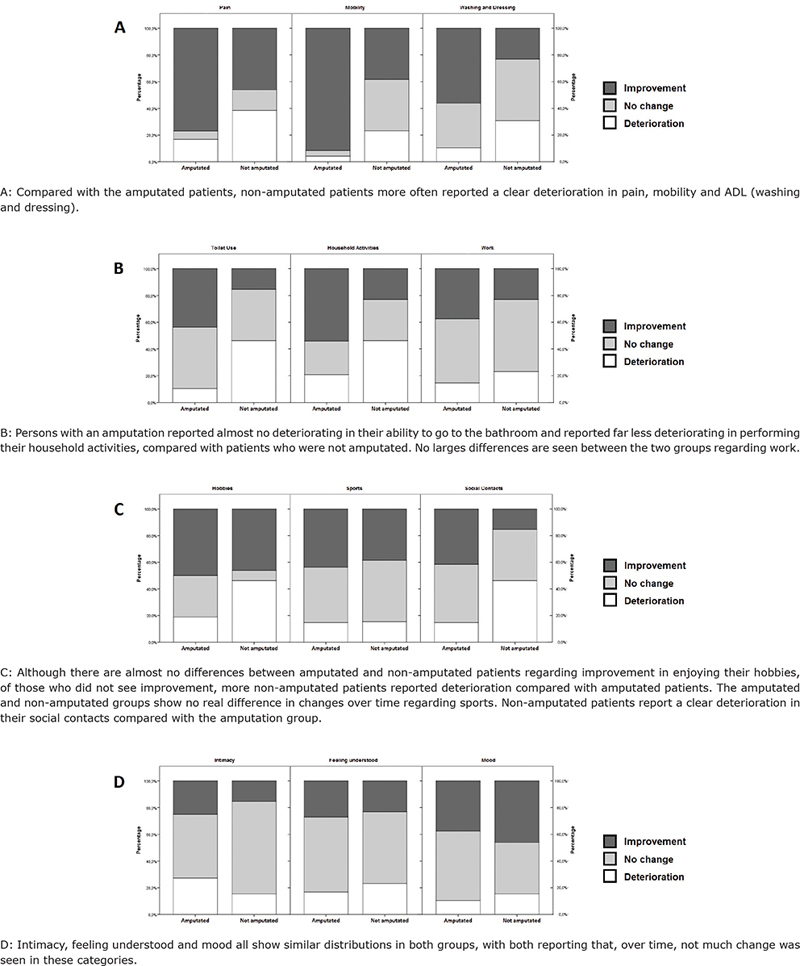

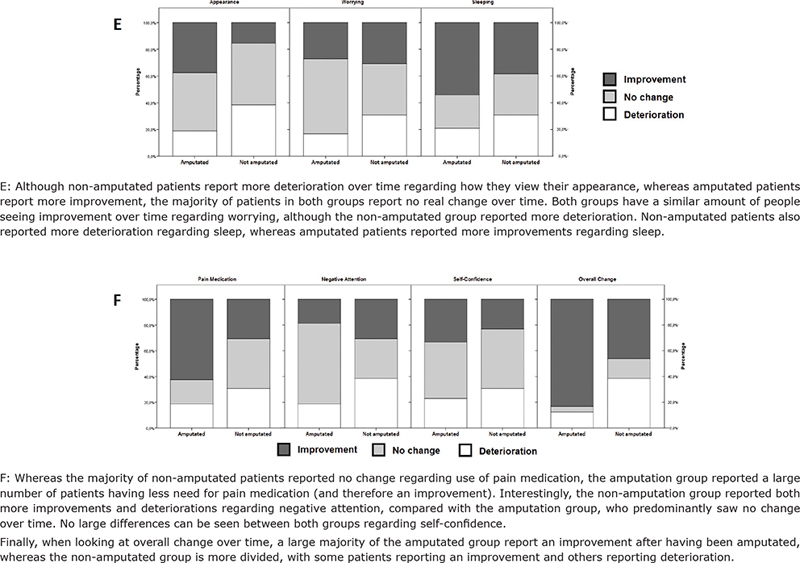

In a previous study in our clinic including patients who had been amputated because of therapy-resistant CRPS-I the same thorough evaluation by the same team was applied and the patients were seen in the same time period. In this study and the previous one the same 19 questions had been asked (18). When comparing outcomes of both studies, change in pain, mobility, pain medication and overall change were better in the amputation group (Appendix I). These results confirm previous studies stating amputations can reduce pain, increase mobility and overall QoL (17,18,21). Those who received amputations generally also experienced improvements in their ADL, toilet use and household work. These differences between groups might be the result of being amputated, indicating that our selection criteria are valid and we rightfully selected those who would benefit most from amputations (28,29). On the other hand it could also indicate that amputations should have been opted for those who were denied an amputation. To answer these questions ideally a randomized controlled trial (RCT) needs to be conducted. Since the number of patients who request amputations because of long-standing therapy-resistant CRPS-I is low, an RCT with adequate sample size seems impossible and a large case-series seems to be the only feasible option to gain more insight into, to amputate or not. We believe that the current data support our decision-making process, and that improvements in patients’ lives as seen in previous studies are based on this process (28,29). Those who were expected to show the greatest improvements based on their resilience, expectation-management and psychological well-being, and those who had tried all other treatment options without effect, were amputated (20,21).

In a number of facets of life no large differences (nor changes over time) between the amputation group and non-amputation group are visible, such as sports, intimacy, feeling understood, worrying and self-confidence (Appendix I). This might be related to the duration of CRPS-I and that these facets of life have been established (long) before these patients visited our clinic.

One of the main criteria for eligibility for amputation is the therapy-resistance of CRPS-I Interestingly, all participants had received treatments for their CRPS-I after being told that amputation is not an option. In our study a substantial number of participants reported improvement following these additional treatments, supporting the importance of viewing amputations in CRPS-I only as the very last resort when all other treatments have failed.

The HADS-D outcomes suggested 5 participants might be depressed.

Some participants however had comorbidity that impacted their mood, making it difficult to attribute the outcomes of the HADS-D to their CRPS-I. A previous study at our institute with patients with CRPS-I who did have an amputation, found a mean HADS-D score of 3.2. This score indicates that these participants fall within the range of Dutch norm values, indicating not being depressed (18,24,30). In the current group however, a median HADS-D score of 6 was found, suggesting that we either made a wise choice to not amputate these patients as they are more depression-prone or participants became depressed because of not being amputated. Unfortunately, we don’t have data of depression scores at the time of outpatient clinic visit, so comparisons cannot be made.

Finally, participants were asked in the interviews how they experienced their visit to our clinic. A majority of participants reported that they did not feel part of the decision-making process at that time. One can, however, wonder if shared decision making has a place in a specialized team as this; the team only answers the question whether they think patients are suitable for amputation or not. This answer is given to these patients and referring physician, who then together decide how to proceed. Emphasizing this role of the amputation team to patients and referring physicians (an advising one) is therefore essential, as is giving clear explanations to patients as to why amputation is not an option (20, 28). The lack of feeling part of the team or the decision-making process might have influenced the reason why we have not seen these patients back in our clinic after having been denied the amputation.

A weakness of this study is a low number of participants. It is therefore unclear whether the enrolled participants in this study are representative of the entire patient group. It might be that the participants had more positive views toward the amputation team or had more negative views and saw this study as an opportunity to ventilate their experience. Another weakness of the study is that the interview was conducted over the phone, making it more difficult to observe non-verbal communication. We neither asked our participants what type of medication they had been using nor did we elaborate on the type of pain rehabilitation received. Furthermore, recalling change in aspects of QoL over a longer period (2–8 years) can be challenging.

The strength of this study is that it uses the same questionnaires as our previous study conducted with patients who did receive amputations. Reflecting upon ones’ practice is an important part of being a physician. The results of this study provided us with patients’ experiences with the decision-making process and the course of CRPS-I over time, after being denied an amputation, but perhaps most importantly, it shows us that we as medical professionals should be thorough in labeling CRPS-I as truly therapy resistant.

In conclusion all participants, after being denied an amputation at the outpatient clinic, received further treatment and were in fact (at the time) not therapy resistant. Furthermore, deterioration of QoL is not necessarily the only course of long-standing CRPS-I.

What we can learn from this study:

- While considering amputation for CRPS-I, verify that all other feasible treatment options, as mentioned in the CRPS-I guidelines, have been tried (11,12).

- Even in patients suffering from longstanding CRPS-I treatment can improve pain and QoL.

- Thorough assessment of physical signs, extent of disability, treatments received, and patient’s expectations are important in deciding whether to amputate or not.

FUNDING SOURCES

No declared.

REFERENCES

- Urits I, Shen AH, Jones MR, Viswanath O, Kaye AD. Complex regional pain syndrome, current concepts and treatment options. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2018; 22(2): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-018-0667-7

- Marinus J, Moseley GL, Birklein F, Baron R, Maihöfner C, Kingery WS, et al. Clinical features and pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10(7): 637–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70106-5

- Birklein F, Schlereth T. Complex regional pain syndrome-significant progress in understanding. Pain 2015; 156(Suppl 1): 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460344.54470.20

- Geertzen JHB, Bodde MI, Van den Dungen JJA, Dijkstra PU, Den Dunnen WFA. Peripheral nerve pathology in patients with severely affected complex regional pain syndrome type I. Int J Rehabil Res 2015; 38(2):121–130. https://doi.org/10.1097/mrr.0000000000000096

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RSGM, Birklein F, Marinus J, Maihofner C, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain 2010; 150(2): 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.030

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, Saltz S, Bertram M, Backonja M, et al. External validation of IASP diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome and proposed research diagnostic criteria. Pain 1999; 81(1–2): 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00011-1

- Vladimir Tichelaar YIG, Geertzen JHB, Keizer D, Paul van Wilgen C. Mirror box therapy added to cognitive behavioural therapy in three chronic complex regional pain syndrome type I patients: A pilot study. Int J Rehabil Res 2007; 30(2): 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1097/mrr.0b013e32813a2e4b

- Rothgangel AS, Braun SM, Beurskens AJ, Seitz RJ, Wade DT. The clinical aspects of mirror therapy in rehabilitation: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Rehabil Res 2011; 34(1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/mrr.0b013e3283441e98

- Hwang H, Cho S, Lee J-H. The effect of virtual body swapping with mental rehearsal on pain intensity and body perception disturbance in complex regional pain syndrome. Int J Rehabil Res 2014; 37(2): 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1097/mrr.0000000000000053

- Lagueux E, Charest J, Lefrançois-Caron E, Mauger M-E, Mercier E, Savard K, et al. Modified graded motor imagery for complex regional pain syndrome type 1 of the upper extremity in the acute phase: A patient series. Int J Rehabil Res 2012; 35(2): 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1097/mrr.0b013e3283527d29

- NVA/VRA. Richtlijn Complex Regionaal Pijn Syndroom type 1 [Internet]. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/complex_regionaal_pijn_syndroom_type_1/startpagina_-_complex_regionaal_pijnsyndroom.html. 2021 [cited 2022 Oct 7]. Available from: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/complex_regionaal_pijn_syndroom_type_1/startpagina_-_complex_regionaal_pijnsyndroom.html

- Royal College of Physicians. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2022 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/complex-regional-pain-syndrome-adults.

- Casale R, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P. The therapeutic approach to complex regional pain syndrome: Light and shade. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015; 33(Suppl 88): 126–139.

- Van Velzen GAJ, Perez RSGM, Van Gestel MA, Huygen FJPM, Van Kleef M, Van Eijs F, et al. Health-related quality of life in 975 patients with complex regional pain syndrome type 1. Pain 2014; 155(3): 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.12.017

- Tan ECTH, Van de Sandt-Renkema N, Krabbe PFM, Aronson DC, Severijnen RSVM. Quality of life in adults with childhood-onset of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type I. Injury 2009; 40(8): 901–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2009.01.134

- Mouraux D, Lenoir C, Tuna T, Brassinne E, Sobczak S. The long-term effect of complex regional pain syndrome type 1 on disability and quality of life after foot injury. Disabil Rehabil 2019; 43(7): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1650295

- Ayyaswamy B, Saeed B, Anand A, Chan L, Shetty V. Quality of life after amputation in patients with advanced complex regional pain syndrome: A systematic review. EFORT Open Rev 2019; 4(9): 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1302/2058-5241.4.190008

- Geertzen JHB, Scheper J, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU. Outcomes of amputation due to long-standing therapy-resistant complex regional pain syndrome type I. J Rehabil Med 2020; 52(8): 3–11. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2718

- Bodde MI, Schrier E, Krans HK, Geertzen JHB, Dijkstra PU. Resilience in patients with amputation because of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type I. Disabil Rehabil 2014; 36: 838–843. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.822023

- Schrier E, Geertzen JHB, Scheper J, Dijkstra PU. Psychosocial factors associated with poor outcomes after amputation for complex regional pain syndrome type-I. PLoS One 2019; 14(3): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0213589

- Krans-Schreuder HK, Bodde MI, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU, Van den Dungen JA, Den Dunnen WF, et al. Amputation for long-standing, therapy-resistant type-I complex regional pain syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(24): 2263–2268. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.l.00532

- Goebel A, Lewis S, Phillip R, Sharma M. Dorsal root ganglion stimulation for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) recurrence after amputation for CRPS, and failure of conventional spinal cord stimulation. Pain Practice 2018; 18(1): 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12582

- Bodde MI, Dijkstra PU, den Dunnen WFA, Geertzen JHB. Therapy-resistant complex regional pain syndrome type I: To amputate or not?. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(19): 799–805. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.j.01329

- Bocéréan C, Dupret E. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in a large sample of French employees. BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14: 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0354-0

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002; 52(2): 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3

- Kang JE, Kim YC, Lee SC, Kim JH. Relationship between complex regional pain syndrome and working life: A Korean study. J Korean Med Sci 2012; 27(8): 929–933. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2012.27.8.929

- Geertzen JHB, Dijkstra PU, Groothoff JW, Ten Duis HJ, Eisma WH. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the upper extremity – A 5.5-year follow-up. Part II. Social life events, general health and changes in occupation. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1998; 279: 19–23.

- Schrier E, Dijkstra PU, Zeebregts CJ, Wolff AP, Geertzen JHB. Decision making process for amputation in case of therapy resistant complex regional pain syndrome type-I in a Dutch specialist centre. Med Hypotheses 2018; 121: 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2018.08.026

- Bodde MI, Dijkstra PU, Schrier E, Van Den Dungen JJ, Den Dunnen WF, Geertzen JHB. Informed decision-making regarding amputation for complex regional pain syndrome type I. J Bone Joint Surg 2014; 96: 930–934.

- Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 1997; 27(2): 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291796004382

Appendix I. Reported improvements and deteriorations in patients with long-standing Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type I; Comparison of amputated and not amputated groups.

Explanation of the figures: