ORIGINAL REPORT

EFFECTIVENESS OF ULTRASOUND-GUIDED VS ELECTRICAL-STIMULATION-GUIDED BOTULINUM TOXIN INJECTIONS IN TRICEPS SURAE SPASTICITY AFTER STROKE: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED STUDY

Isabelle HAURET, MD, MSc1, Lech DOBIJA, PT, MSc1, Pascale GIVRON, MD1, Anna GOLDSTEIN, MD, MSc1, Bruno PEREIRA, PhD2 and Emmanuel COUDEYRE, MD, PhD1

From the 1Departement of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital, Clermont Auvergne University, Institut national de recherche agrononomique et environnement, France and 2Innovation and Clinical Research, Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital, Clermont-Ferrand, France

Objective: To compare the efficacy of botulinum toxin injections using ultrasound-guidance vs electrical-stimulation-guidance in triceps surae (soleus and gastrocnemius) spasticity after stroke.

Design: A clinical, single-centre, prospective, interventional, single-blind, cross-over, randomized trial, with outpatients in the tertiary care hospital. After randomization, subjects received electrical-stimulation-guided, followed by ultrasound-guided abobotulinumtoxinA injection (n = 15), or the same 2 procedures in the reverse order (n = 15) with the same operator, 4 months apart. The primary endpoint was the Tardieu scale with the knee straight at 1 month after injection.

Results: The 2 groups did not differ in Tardieu scale score (effect size = 0.15, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) –0.22 to 0.51, p = 0.43). In addition, the muscle localization technique used had no influence on walking speed, pain on injection or spasticity, assessed at 1 month after the injection, using the modified Ashworth scale. Ultrasound-guided injections were faster to administer than electrical-stimulation-guided injections.

Conclusion: In agreement with previous research, no differences were found in the efficacy of ultrasound-guided or electrical-stimulation-guided abobotulinumtoxinA injections in triceps surae spasticity after stroke. Both techniques are of equal use in guiding muscle localization for botulinum toxin injections in spastic triceps surae.

LAY ABSTRACT

This study compared the efficacy of 2 techniques used to localize botulinum toxin (BoNT-A) injections in triceps surae (soleus and gastrocnemius) spasticity after stroke: ultrasound-guidance vs electrical-stimulation-guidance. The results show that electrostimulation guidance and ultrasound guidance have the same efficacy for BoNT-A injections in triceps surae spasticity. The technique used had no influence on spasticity, walking speed, or pain on injection. Administration of ultrasound-guided injections was faster than electrical-stimulation-guided injections.

Key words: botulinum toxin; triceps surae; ultrasonography; Tardieu scale.

Citation: J Rehabil Med 2023; 55: jrm11963. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v55.11963

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: May 25, 2023; Published: July 11, 2023

Correspondence address: Emmanuel Coudeyre, Service de Médecine Physique et de Réadaptation, Hopital Louise Michel, CHU Clermont-Ferrand, Route de Chateaugay, FR-63118 Cébazat, France. E-mail: ecoudeyre@chu-clermontferrand.fr

The efficacy of botulinum toxin injections on spasticity in vascular hemiplegic patients has been widely demonstrated (1). However, different techniques exist for the injection and, more importantly, for muscle localization. The most frequently used techniques are physical palpation, electrical stimulation, electromyography and, more recently, ultrasonography. The supposed advantages of ultrasonography are painless localization (2), speed (3), precision (2) and, consequently, safety, because ultrasonography could contribute to avoidance of complications linked to subcutaneous, intravascular or overly deep injections (4).

Some studies have compared the different muscle localization techniques during botulinum toxin injections. Two studies have shown the superiority of ultrasonography vs palpation localization in adults after stroke. The first study included 49 patients with injection in the gastrocnemius muscle (5) and the second included 60 patients with injection in the wrist and/or finger flexors (6). A literature review (7) comparing 4 tracking methods (physical palpation, electromyography, electrical stimulation, and ultrasonography) found advantages and disadvantages of each method. The advantages of ultrasonography were the visualization of neurovascular structures during the injections. However, the efficacy of the technique depends to a great extent on the operator’s abilities. Another literature review (8) evaluated the impact of the different localization techniques on the efficacy of botulinum toxin injection during the treatment of spasticity or dystonia. The authors reported a high level of proof (grade A) for effectiveness according to the instrumental localization used (ultrasonography, electrical stimulation, or electromyography) compared with simple palpation in treating spasticity of the arms, spastic equinus after a stroke, and the consequences of cerebral palsy in children. No instrumental localization technique showed any superiority compared with another. Although the different instrumental localization techniques seem to be more effective than simple palpation, no recommendations can be made to favour one technique over another.

A recent study comparing ultrasound- and electrostimulation-guided botulinum toxin injections for post-stroke spastic equinus foot (9) did not show any significant differences between the 2 groups with regard to ankle range of motion, modified Ashworth scale, Brunnstrom stages, Barthel index or walking speed, although some methodological limits should be noted. First, no primary endpoint was specified and the sample size was not calculated before starting the study. Secondly, assessments were performed at 2 weeks after injection (before peak efficacy of botulinum toxin) and at 3 months after injection (botulinum toxin was no longer effective). Thirdly, the authors used 2 different commercial preparations of BoNT-A; hence the doses injected in the 2 groups were probably not comparable.

The main aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of 2 localization techniques, ultrasonography and electrical stimulation, on BoNT-A injections for triceps surae spasticity after stroke. It was hypothesized that localization by ultrasonography was more effective on spasticity than localization by electrical stimulation. Secondary objectives were to compare the tolerance (pain during the injection), ease of practice (length of time for the localization and injection) and disability (walking speed) of the 2 techniques.

METHODS

Study design

The protocol for this single-centre, prospective, controlled, randomized study with single blinding and crossover has been published previously (10). The study was performed in the physical medicine and rehabilitation department of Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital, Auvergne Rhone Alpes state, France. The patients received 2 injections, each administered using a different guidance technique, 4 months apart. Randomization was used to determine which technique was used in the first and second instances. Initial assessment of patients included in the study was performed just prior to the first injection. Evaluation comprised clinical assessment of the triceps surae spasticity based on the Tardieu and modified Ashworth scales, and instrument-based walking speed using GAITRite (CIR Systems, Sparta, NJ, USA). The 2 follow-up visits took place 1 month after each BoNT-A injection and consisted of evaluation of the spasticity of the triceps surae by using the Tardieu and modified Ashworth scales and walking speed with GAITRite.

All evaluations were performed by an experienced physiotherapist who was blinded to group allocation.

The study protocol was approved by the medical ethics committee Sud-Est 1, (number 2012-22) and the ANSM (Agence nationale de sécurité des medicaments et des produits de santé; the French National Agency of Medicine and Health Products Safety). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

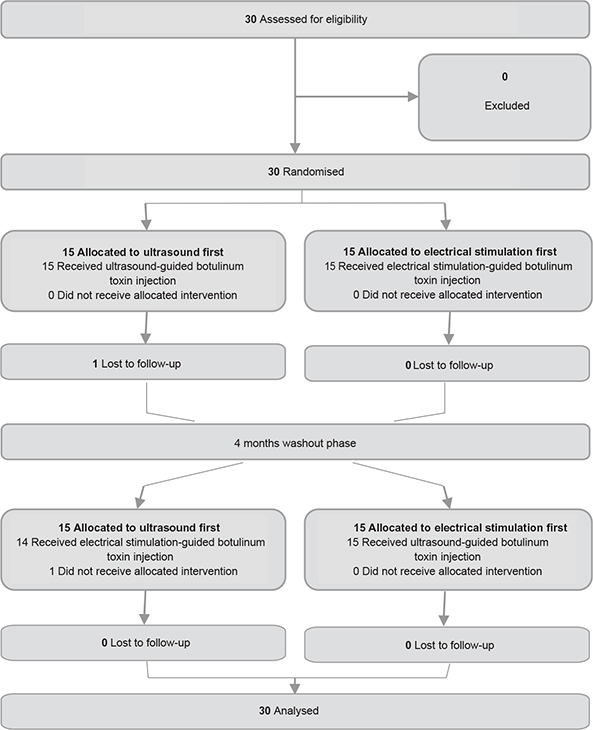

Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were: age 18–80 years, hemiplegic sequelae of stroke, triceps surae spasticity (modified Ashworth scale score > 1/4), ability to provide written consent. The exclusion criteria were: botulinum toxin injection within at least the last 3 months, previous experience with ultrasound-guided botulinum toxin injection, contraindication to botulinum toxin injection, implant with a pacemaker, history of ankle arthrodesis. All participants were included between 19 November 2013 and 18 September 2018.

The following data were collected for each patient: age, sex, time since stroke, side affected by the cerebral lesion, current treatments and dosages (for managing spasticity and pain), date of the first botulinum toxin injection and severity of deficit: Functional Ambulation Classification modified (11).

Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of the above-described sequences: ultrasound-guided injection then electrical-stimulation-guided injection, or vice versa. A permuted-block randomization was used with a computer-generated random allocation (Stata 13, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), with a 1:1 ratio.

Intervention

The first injection was performed using ultrasound-guided localization (Sonosite Edge, FUJIFILM Sonosite France, Paris, France with a 6–13 MHz probe) or electrical-stimulation-guided localization (Dantec Clavis, Natus Medical Incorporated, San Carlos, CA, USA) in the triceps surae. The second injection was performed 4 months later with the alternate localization technique. Different needles were used for cost reasons. Electrical-stimulation needles (26G, 2.80€) were used for electrical-stimulation-guided injection. Intramuscular needles (21G, 0.0116€) were used for ultrasonography. A total of 500 units of BoNT-A (Dysport), were injected in 4 distinct areas of the triceps surae: 200 units in soleus (2 points), 150 units in lateral gastrocnemius (1 point), and 150 units in medial gastrocnemius (1 point). The drug was reconstituted with 2 mL normal saline per 500 U. All injections were performed by a single injector who has extensive experience with the 2 tracking techniques.

Outcome measures

The primary end-point is spasticity of triceps surae on the Tardieu scale (12) while keeping the knee straight. This scale rates spasticity as the difference between the reactions to stretch at Tardieu’s 2 extreme velocities, the slowest and the fastest possible speed of stretch for the examiner. The slow velocity of the first stretch remains below the threshold for any significant stretch reflex and provides an assessment of the passive range of motion. In contrast, the stretch at the fastest velocity maximizes involvement of the stretch reflex. If any spasticity is present, the physician during this fast stretch encounters a sensation of catch-and-release, or of clonus, fatigable or not, depending on the amount of spasticity (11). The main outcome was measured on the day of injection and 1 month later.

The secondary end-points were: other components of the Tardieu scale (quality of muscle reaction (X) at slow speed and fast speed, angle of apparition of the muscle reaction (Y) at slow speed and fast speed), assessment of the triceps surae spasticity on the modified Ashworth scale, walking speed, pain during injection and duration of tracking and injection. Comfortable walking speed, with shoes was measured with an instrumented walkway analysis by GAITRite®. The mean speed and cadence of walking, length of step and stride over two 10-m journeys was calculated.

The length of time for the localization and the injection were measured by the operator, using a stopwatch started after preparation of the equipment and before the start of tracking and stopped at the end of the injection. The pain felt during the injection was measured by the patient, using a vertical analogical visual pain evaluation scale (VAS) immediately after injection.

Statistical analysis

The sample size estimation has been described previously (10). To demonstrate a minimum difference of 7.12° with regard to change in stretch angle at low and high velocity of passive movement (using the Tardieu scale) between ultrasound- and electrical-stimulation-guided injection and for an effect size (ES) of 0.8 (with an expected standard deviation (SD) of the difference of 8.9°) (12), 15 patients per sequence (ultrasound then electrical stimulation vs electrical stimulation then ultrasound) were needed for a 2-sided type I error = 5%, statistical power = 80%, and intra-individual correlation coefficient = 0.5 (owing to the cross-over design).

Statistical analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis with Stata v13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for a 2-sided type I error = 5%. Continuous data are described as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range; IQR), according to the statistical distribution. Normality was studied with the Shapiro–Wilk test. The primary endpoint, variation in stretch angle at low and high velocity of passive movement (with the Tardieu scale) and other continuous variables were compared between groups by using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for cross-over designs, which took into account the effect of treatment group (ultrasound vs electrical stimulation), period, sequence and participant (as a random effect). The carry-over effect was evaluated and found not significant. The normality of residuals was assessed. When appropriate, a logarithmic transformation was proposed to achieve the normality of the dependant variable. For categorical variables, a generalized linear mixed model was applied, which took into account the aforementioned effects. The results were presented as suggested by CONSORT and Vancouver guidelines, quantifying findings with ESs and presenting them with appropriate indicators of measurement error or uncertainty (i.e. as CIs).

RESULTS

A total of 30 participants were included in the study and randomly assigned to 2 groups. All patients were able to walk. One participant was lost to follow-up for unknown reasons after injection with ultrasound guidance and evaluation and did not receive the second injection with electrical-stimulation guidance. The follow-up lasted until 12 February 2019, the end of the study. Characteristics of participants are shown in Table I.

The 2 groups (ultrasound or electrical-stimulation localization first) did not differ in spasticity of the triceps surae at 1 month after the injection (mean (SD) Tardieu score –1.50 ± 7.91 (16.4 ± 5.5 (before injection) vs 26.8 ± 7.6 (after injection) at initial evaluation and 19.5 ± 6.7 (before injection) vs 28.3 ± 8.0 (after injection) at 1 month for ultrasound localization) vs –0.52 ± 6.59 (16.0 ± 6.5 (before injection) vs 26.9 ± 10.3 (after injection) at initial evaluation and 18.1 ± 6.2 (before injection) vs 28.4 ± 10.4 (after injection) at 1 month for electrical stimulation), ES = 0.15 95% CI [–0.22; 0.51], p = 0.43), walking speed over 10 m at 1 month or pain during the injection. However, localization was significantly faster with ultrasonography than with electrical stimulation (mean 156 ± 63 vs 218 ± 89 s, p < 0.001). The results are shown in Table II.

There were no differences in secondary outcomes, particularly concerning speed, cadence of walking, length of step and stride.

Adverse events were observed in both groups, 4 after electrical-stimulation-guided injection (pruritus of the calf, wound on the outside of the ankle, bruise on the foot, and bronchitis) and 2 after ultrasound-guided injection (pain in the knee, and pain at the injection site). The calf pruritus occurred the day after botulinum toxin injection, without a rash, and resoved completely in less than 24 h. The ankle wound, linked to a conflict with a splint, is more related to the recurrence of spasticity. Haematoma at the distal part of the lower limb appeared approximately 1 week after the injection. It was completely resolved at the follow-up visit. One patient described nocturnal pain at the injection site, which lasted more than 1 month. Three months post-injection knee pain while walking was related to the recurrence of spasticity. Ultimately, 2 adverse experiences linked to the injection occurred after electrical-stimulation-guided injection and 1 after ultrasound-guided injection. No weakness of neighbouring muscles was reported by patients.

DISCUSSION

This randomized controlled study did not show any difference in efficacy between ultrasound-guided and electrical-stimulation-guided BoNT-A injection in soleus and gastrocnemius spasticity after stroke. ES for the primary endpoint was 0.15 (95% CI –0.22 to 0.51; p = 0.43), confirming that this study was negative. More precisely, the study did not confirm the assumption that localization by ultrasonography was more effective for spasticity than localization by electrical stimulation.

The study population was sufficiently comparable to another study cohort with post-stroke spastic upper limb receiving botulinum toxin injections (1), consisting of 60% men, age 53.7 ± 13.7 years. The current study population was smaller, with a smaller age range (34–74 years vs 17–83 years). The time since the stroke was shorter (3 years vs 5 years). Therefore, the results of this study might be generalizable to the vascular hemiplegic population receiving botulinum toxin injections.

A limitation of this study is the difficulty in generalizing the results because the study involved only a single brand of botulinum toxin (Dysport) to treat spasticity of a muscle group (soleus and gastrocnemius) after a pathology (stroke). However, there is no evidence, based on published data or our experience, to suggest that the results would be different with a botulinum toxin from another brand, or by targeting patients with spasticity related to a different pathology.

Since the study has a cross-over design, a potential limitation could be that, after determining the specific anatomy of patients by means of ultrasound, the accuracy and, possibly, the efficacy of subsequent treatment using electrical-stimulation localization might be affected. However, as the ultrasound images were not archived it was not possible for the injector to use the ultrasound anatomy of each patient when applying the second injection.

The current study results are in agreement with other published results. One study comparing injections in the triceps surae (5) also found no difference in Tardieu score between the 2 groups (ultrasound and electrical-stimulation guidance). The number of participants included was limited (16 in the electrical-stimulation group and 17 in the ultrasonography group). Passive range of motion was significantly (p = 0.004) greater in the ultrasonography vs electrical-stimulation group, but with no clinical meanings (only a few °). The same authors published a study on the upper limbs (6) and found no clinical difference in Tardieu or modified Ashworth scores between the 2 groups at 1 month after injection. The current study was not statistically underpowered. If the sample size was estimated according to literature in order to highlight an ES of 0.8 (12), the observed ES must be interpreted as negligible according to Cohen’s recommendations (13),which define ES bounds as: small: 0.2 < ES < 0.5, medium: 0.5 < ES < 0.8, and large (“grossly perceptible and therefore large”): ES ≥ 0.8. To show such difference, 450 patients would be needed for a cross-over design study, which seems neither relevant nor appropriate.

The current study found no difference between electrical-stimulation and ultrasonography injection guidance in pain, despite the use of different sized needles: needles used for ultrasound-guided injection were 21G, but those used for electrical-stimulation-guided injection were thinner (26G). A difference in pain was found in favour of ultrasound, although the pain during injection was greater for ultrasound-guided injection because the needles were larger, this was balanced by the pain due to electrical stimulation. Therefore, for most patients, needle-stick injuries were mainly responsible for the pain, rather than the electrical stimulation (14). In fact, in the previous study, the better-tolerated needles were those used with electrical stimulation (14).

Localization was achieved significantly faster using ultrasound-guidance than electrical-stimulation-guidance (2 min 29 s vs 3 min 38 s). Despite very few data published concerning the speed of localization during ultrasound-guided injections, the results vary. One author with extensive experience described a mean localization and injection time of 5 s for the superficial muscles and 30 s for the deepest muscles (3). Another study (15) found an increase in duration of the complete procedure from 5 to 10 min when 4 injections were performed with ultrasound localization. The time taken to start the timer and the operator’s experience probably explains these differences.

The measurement scales used in the current study may not be able to detect any difference between groups. The measures lack sufficient reproducibility or are not sensitive to change to demonstrate a difference. However, to our knowledge, no other clinical means exist to assess spasticity.

CONCLUSION

Both localization techniques (ultrasound-guided and electrical-stimulation-guided) seem relevant for BoNT-A injections, provided that the operator is trained and has sufficient experience. The choice of technique may be based on the patient’s preference; some patients describe better tolerance to injections using certain localization techniques. Above all, the choice must also take into account the muscle that is to be injected (using ultrasonography for small or deep muscles). The combined use of both techniques may also be of interest in certain situations (e.g. localization of muscles in the forearm) in order to reduce the duration and improve efficacy of the localization. In practice, ultrasound-guided injections of botulinum toxin are increasingly being used (16) (NCT02566837, NCT02469948), although this localization technique remains less used than electrical stimulation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Data are available from the corresponding author, given reasonable notice.

IPSEN (Institut des produits de synthèse et d'extraction naturelle) for 39 000 euros provided funding for the ultrasound. Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital provided funding for the research appel d'offre interne 2012 for 14 500 euros.

The results are reported in accordance with the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Statement.

REFERENCES

- Marque P, Denis A, Gasq D, Chaleat-Valayer E, Yelnik A, Colin C; et al. Botuloscope: 1-year follow-up of upper limb post-stroke spasticity treated with botulinum toxin. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2019; 62: 207–213. DOI: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.06.003

- Schroeder AS, Berweck S, Lee SH, Heinen F. Botulinum toxin treatment of children with cerebral palsy – a short review of different injection techniques. Neurotox Res 2006; 9: 189–196. DOI: 10.1007/BF03033938

- Berweck S, Schroeder AS, Fietzek UM, Heinen F. Sonography-guided injection of botulinum toxin in children with cerebral palsy. Lancet 2004; 363: 249–250. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15351-2

- Berweck S, Heinen F. Use of botulinum toxin in pediatric spasticity (cerebral palsy). Mov Disord 2004; 19: S162–167. DOI: 10.1002/mds.20088

- Picelli A, Tamburin S, Bonetti P, Fontana C, Barausse M, Dambruoso F, et al. Botulinum toxin type A injection into the gastrocnemius muscle for spastic equinus in adults with stroke: a randomized controlled trial comparing manual needle placement, electrical stimulation and ultrasonography-guided injection techniques. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 91: 957–964. DOI: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318269d7f3

- Picelli A, Lobba D, Midiri A, Prandi P, Melotti C, Baldessarelli S, et al. Botulinum toxin injection into the forearm muscles for wrist and fingers spastic overactivity in adults with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial comparing three injection techniques. Clin Rehabil 2014; 28: 232–242. DOI: 10.1177/0269215513497735

- Walker HW, Lee MY, Bahroo LB, Hedera P, Charles D. Botulinum toxin injection techniques for the management of adult spasticity. PM R 2015; 7: 4174–4127. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.09.021

- Grigoriu AI, Dinomais M, Rémy-Néris O, Brochard S. Impact of injection-guiding techniques on the effectiveness of botulinum toxin for the treatment of focal spasticity and dystonia: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 96: 2067–2078.e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.05.002

- Turna IF, Erhan B, Gunduz NB, Turna O. The effects of different injection techniques of botulinum toxin a in post-stroke patients with plantar flexor spasticity. Acta Neurol Belg 2020; 120: 639–643. DOI: 10.1007/s13760-018-0969-x

- Morel C, Hauret I, Andant N, Bonnin A, Pereira B, Coudeyre E. Efficacy of two injection-site localisation techniques for botulinum toxin injections: a single-blind, crossover, randomised trial protocol among adults with hemiplegia due to stroke. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e011751. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011751

- Park CS, An SH. Reliability and validity of the modified functional ambulation category scale in patients with hemiparalysis. J Phys Ther Sci 2016; 28: 2264–2267. DOI: 10.1589/jpts.28.2264

- Gracies JM. Evaluation de la spasticité – Apport de l’échelle de Tardieu. Motricité Cérébrale 2001; 22: 1–16.

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd edn). Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Erlbaum; 1988.

- Mathevon L, Davoine P, Tardy D, Bouchet N, Gornushkina L, Perennou D. Pain during botulinum toxin injections in spastic adults: influence of patients’ clinical characteristics and of the procedure. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2018; S61: e359. DOI.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2018.05.837

- Singh P, Joshua AM, Ganeshan S, Suresh S. Intra-rater reliability of the modified Tardieu scale to quantify spasticity in elbow flexors and ankle plantar flexors in adult stroke subjects. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2011; 14: 23–26. DOI: 10.4103/0972-2327.78045

- Lee JH, Lee SH, Song SH. Clinical effectiveness of botulinum toxin type B in the treatment of subacromial bursitis or shoulder impingement syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2011; 27: 523–528. DOI: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31820e1310