SHORT COMUNICATION

INPATIENT MULTIMODAL REHABILITATION AND THE ROLE OF PAIN INTENSITY AND MENTAL DISTRESS ON RETURN-TO-WORK: CAUSAL MEDIATION ANALYSES OF A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL

Lene AASDAHL, PhD1,2, Tom Ivar Lund NILSEN, PhD1,3, Paul Jarle MORK, PHD1, Marius Steiro FIMLAND, PhD2,4,5 and Eivind Schjelderup SKARPSNO, PhD1,6

From the 1Department of Public Health and Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, 2Unicare Helsefort Rehabilitation Centre, Rissa, 3Clinic of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, St Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, 4Department of Neuromedicine and Movement Science, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, 5Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, St Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim and 6Department of Neurology and Clinical Neurophysiology, St Olavs Hospital, Trondheim, Norway.

Objective: Studies suggest that symptom reduction is not necessary for improved return-to-work after occupational rehabilitation programmes. This secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial examined whether pain intensity and mental distress mediate the effect of an inpatient programme on sustainable return-to-work.

Methods: The randomized controlled trial compared inpatient multimodal occupational rehabilitation (n = 82) with outpatient acceptance and commitment therapy (n = 79) in patients sick-listed due to musculoskeletal and mental health complaints. Pain and mental distress were measured at the end of each programme, and patients were followed up on sick-leave for 12 months. Cox regression with an inverse odds weighted approach was used to assess causal mediation.

Results: The total effect on return-to-work was in favour of the inpatient programme compared with the control (hazard ratio (HR) 1.96; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.15–3.35). There was no evidence of mediation by pain intensity (indirect effect HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.61–1.57, direct effect HR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.02–3.90), but mental distress had a weak suppression effect (indirect effect HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.59–1.36, direct effect HR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.13–4.26).

Conclusion: These data suggest that symptom reduction is not necessary for sustainable return-to-work after an inpatient multimodal occupational rehabilitation intervention.

LAY ABSTRACT

The work disability paradigm posits work disability as a psychosocial and work-related issue. However, it is unclear whether clinical symptoms, such as pain intensity and mental distress, mediate the effectiveness of return-to-work interventions. The results of this study support existing evidence suggesting that symptom reduction is not necessary for successful return-to-work. Symptoms of mental distress slightly suppressed the favourable effect of the intervention, but this estimate was imprecise. Future studies should explore whether individuals with mental distress require an adapted treatment approach.

Key words: occupational therapy; work; pain intensity; chronic pain; mental health; sick leave; return-to-work.

Citation: J Rehabil Med 2024; 56: jrm18385. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v56.18385.

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Submitted: Aug 10, 2023; Accepted: Dec 6, 2023; Published: Jan 12, 2024

Correspondence address: Lene Aasdahl, Department of Public Health and Nursing, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Postboks 8905, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway. E-mail: lene.aasdahl@ntnu.no

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

Returning to work after long-term sick leave is challenging, and may be affected by biological, psychological, and social mechanisms (1). Multimodal occupational programmes have been recommended to aid sick-listed workers with chronic musculoskeletal pain and mental health conditions (2). To improve the effectiveness of future return-to-work interventions, it is important to understand the causal mechanisms underlying their success.

Previous return-to-work interventions have im-proved work participation, but have, to a lesser extent, been beneficial for health outcomes, such as pain intensity and psychological complaints (3–5). However, it is unclear whether symptom reduction is necessary for successful return-to-work. No previous study has examined the potential mediating role of pain intensity and mental distress on the effect of occupational rehabilitation on return-to-work using analyses that support causal inference. We recently reported that an inpatient multimodal occupational rehabilitation programme was more effective in promoting return-to-work than a less comprehensive outpatient programme with acceptance and commitment therapy for individuals with musculoskeletal and mental health complaints (5). The current study uses an inverse odds weighting approach to assess whether pain intensity and symptoms of mental distress at the end of the programme causally mediated the effect of the inpatient programme on sustainable return-to-work.

METHODS

Study design, participants and interventions

We conducted secondary analyses of a randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov no.NCT01926574) evaluating whether inpatient multimodal occupational rehabilitation was more effective than a less comprehensive outpatient control program on sickness absence (5). The trial enrolled individuals aged 18–60 years who had 2–12 months sick leave with a diagnosis within the musculoskeletal (L), psychological (P) or general and unspecified (A) chapters of the International Classification of Primary Care, Second edition (ICPC-2) (6). The inpatient multimodal occupational rehabilitation programme was both individual and group-based with 2–3 designated coordinators (e.g. physical therapist, psychologist, exercise physiologist, nurse) per group involved in coordinating and executing the intervention. The programme lasted 3.5 weeks with 6–7 h each day except on weekends. It consisted of physical training, mindfulness, psychoeducation, acceptance and commitment therapy, and work-related problem solving. The aim of work-related problem solving was to motivate the participant, clarify the value of work and highlight challenges and resources, and develop a realistic return-to-work plan. The outpatient programme consisted mainly of group-based acceptance and commitment therapy for 2.5 h once a week for 6 weeks. The sessions were led by a physician, or a psychologist trained in acceptance and commitment therapy. In addition, there was a group session with psychoeducation on physical activity led by a physiotherapist, 2 individual sessions with a social worker, and a short individual closing session with a group therapist. In this last session a summary letter was written to the participant’s general practitioner.

A total of 166 participants were included in the randomized controlled trial, but 5 participants recently withdrew their consent and were excluded from the current analysis sample. Further details of the trial, including the inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention programmes and main findings of the trial have been reported previously (5).

Outcome

Sick-leave data was obtained from a linkage to data from the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Service, which contain information on any form of sickness absence and disability benefits in Norway. Information was retrieved on all registered medical benefits for each participant during 12 months of follow-up, and sustainable return-to-work was defined as 1 month without receiving any medical benefits.

Mediators

Data were collected on pain intensity and mental distress using questionnaires at the end of the rehabilitation. Pain intensity was measured by asking participants to rate their average pain level during the last week on a numerical rating scale (0 = no pain; 10 = worst imaginable pain) (7). Mental distress during the last week was measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS) (8), which includes subscales for anxiety and depression, with a maximum score of 21 for each.

Randomization and blinding

Potential participants were identified in the National Social Security System and randomized after an outpatient screening. Blinding of participants and caregivers was not possible. Sickness absence data were provided by employees at the Norwegian Welfare and Labour Service, who were unaware of group allocation. The researchers were not blinded.

Statistical analysis

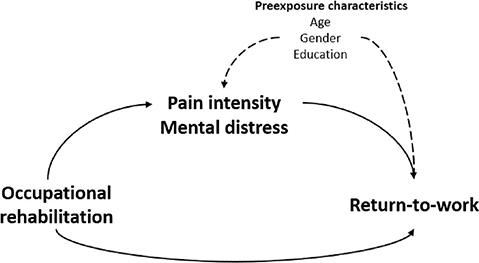

A causal mediation analysis was conducted using the inverse odds weighting procedure (9) that decompose the total effect of the exposure (rehabilitation programme) on the outcome (return-to-work) into a natural direct effect of the exposure on the outcome, and a natural indirect effect through the mediator (e.g. pain intensity). The inverse odds weights were obtained by first regressing the exposure variable (i.e. intervention vs control) on pain intensity assessed at the end of the intervention and control programme using a logistic model. Age (continuous), sex (man, woman), and education (high (college/university) or low) were included as covariates to control for possible mediator-outcome confounding (Fig. 1). The weights were then applied to Cox regression to estimate: (i) the total effect of the intervention as the overall hazard ratio (HR) for sustainable return-to-work comparing the intervention with the control group; (ii) the natural indirect effect of the intervention as the HR for sustainable return-to-work mediated by pain intensity; and (iii) the natural direct effect of the intervention as the HR for sustainable return-to-work not mediated by pain intensity. A similar analysis was then used to assess mediation by anxiety and depression, and in a final model mediation was assessed by all 3 potential mediators. Precision of the HRs are given as 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) from bootstrapping using 1000 replications (10). STATA 17 was used for all analyses (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP).

Fig. 1. Directed acyclic graph for the study. It was hypothesized that the treatment effect of the inpatient occupational rehabilitation programme on return-to-work was mediated by pain intensity and mental distress.

RESULTS

Table I presents baseline characteristics of the 161 participants stratified by intervention and control programme. Information about mediators was missing for 26% and 46% of the participants in the inpatient and outpatient programme, respectively. Overall, mean sick-leave days during the 12-month follow-up was 113 (standard deviation (SD) 86), and 50% achieved sustainable return-to-work. Characteristics of the participants achieving vs not achieving sustainable return-to-work is shown in Table SI.

| Inpatient programme (n = 82) | Outpatient programme (n = 79) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.5 (8.6) | 45.2 (10.4) |

| Women, n (%) | 70 (81) | 61 (76) |

| Higher educationa, n (%) | 30 (37) | 34 (43) |

| Main diagnoses for sick-leave (ICPC-2)b, n (%) | ||

| A: general and unspecified | 3 (4) | 9 (11) |

| L: musculoskeletal | 53 (65) | 40 (50) |

| P: psychological | 26 (32) | 30 (38) |

| Length of sick leave at inclusionb,c, median days (IQR) | 204 (163–265) | 215 (176–262) |

| Pain level (0–10), mean (SD) | 5.0 (2.1) | 4.8 (2.1) |

| HADS mean (SD) | ||

| Anxiety (0–21) | 7.3 (3.9) | 8.6 (4.1) |

| Depression (0–21) | 5.6 (4.0) | 6.6 (4.0) |

| aHigher (tertiary) education (college or university). bBased on data in the medical certificate from the National Social Security System Registry. cNumber of days on sick leave during the last 12 months prior to inclusion. Measured as calendar days, not adjusted for graded sick-leave or part-time job. | ||

| HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. | ||

Overall, the inpatient intervention group had a HR for return-to-work of 1.96 (95% CI 1.15–3.35) compared with the outpatient programme. There was no evidence of mediation by pain intensity (indirect effect HR was 0.98; 95% CI 0.61–1.57). The study observed weak suppression effects of anxiety (indirect effect 0.92; 95% CI 0.63–1.36), depression (HR of 0.96; 95% CI 0.69–1.34), and for anxiety and depression combined (indirect effect HR 0.89; 95% CI 0.59–1.36), resulting in a slightly stronger direct effect of the intervention (HR 2.19; 95% CI 1.13–4.26). Including pain intensity, anxiety, and depression as mediators in the same model gave similar results, with a direct effect HR of 2.22 (95% CI 1.07–4.63) and a total indirect effect HR of 0.88 (95% CI 0.50–1.54).

DISCUSSION

In these secondary analyses of a randomized trial on sick-listed individuals randomized to inpatient multimodal occupational rehabilitation or a less comprehensive outpatient programme, sustainable return-to-work was not mediated by symptom intensity at the end of the inpatient occupational rehabilitation. Although these data indicate that symptoms of mental distress, particularly anxiety, weakly suppressed the favourable effect of the return-to-work intervention, this estimate should be interpreted carefully due to the wide confidence interval.

Previous studies have not assessed whether reducing symptoms is important for a return-to-work intervention to be effective. The current study corroborates previous studies indicating that return-to-work interventions have minor effects on pain intensity, anxiety, and depression (3, 4, 11). However, this is the first study to explore whether such symptoms at the end of the rehabilitation programme mediate the effect of occupational rehabilitation on return-to-work. The findings of the current study support the work disability paradigm, which views chronic musculoskeletal pain as a psychosocial and work-related issue, and not only solely a clinical problem (1).

Since the return-to-work process may be influenced by several interrelated factors, it is recommended that interventions include clinical, psychological, and work environment factors, as well as relevant stakeholders (1, 2). However, the precise mechanisms involved in successful return-to-work remain unclear (12–14). Our results emphasize that clinicians should not only assess clinical factors, such as pain intensity, but also include psychosocial factors. In addition, our findings suggest that the intervention was somewhat less effective for individuals with anxiety, indicating that they may require a different approach to facilitate return-to-work. This could entail a stronger involvement of the workplace, for example using principles from supported employment (5); however, more research is needed on who benefits from what type of intervention.

The main strength of this study was the randomized controlled design and registry data to ensure complete follow-up on sick leave. Although the temporal assessment of possible mediators (i.e. measured after the intervention period) support causal estimation of mediation, we cannot rule out residual mediator-outcome confounding, even in the context of a randomized trial. In addition, missing data on the mediator could lead to selection bias, potentially influencing the results (16).

In conclusion, this study found that the effect of inpatient multimodal occupational rehabilitation on sustainable return-to-work was not mediated by symptom intensity. These results align with the work disability paradigm and support existing evidence suggesting that symptom reduction is not necessary for successful return-to-work intervention. This study found a tendency that mental distress, particularly anxiety, suppresses the favourable effect of such interventions, but this association was too imprecise to draw any firm conclusion. Future studies should explore whether individuals with anxiety require a different treatment approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all involved at Hysnes Rehabilitation Center, Department of Pain and Complex Symptom Disorders and Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at St Olavs University Hospital, as well as the Norwegian Labor and Welfare Service (NAV) for help with collecting data and carrying out the study. We thank project assistant Guri Helmersen for valuable assistance.

The study was funded by the Research Council of Norway and allocated government funding through the Central Norway Regional Health Authority. The funders had no role in the design of the project and collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing the manuscript and in publication decisions.

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Central Norway (Number 2012/1241). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethics standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

REFERENCES

- Loisel P, Durand MJ, Berthelette D, Vezina N, Baril R, Gagnon D, et al. Disability prevention: new paradigm for the management of occupational back pain. Dis Manag Health Out 2001; 9: 351–360.

- Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, Clay F, Gensby U, Jennings PA, et al. Effectiveness of Workplace interventions in return-to-work for musculoskeletal, pain-related and mental health conditions: an update of the evidence and messages for practitioners. J Occup Rehabil 2018; 28: 1–15. DOI: 10.1007/s10926-016-9690-x

- Blonk RWB, Brenninkmeijer V, Lagerveld SE, Houtman ILD. Return to work: a comparison of two cognitive behavioural interventions in cases of work-related psychological complaints among the self-employed. Work Stress 2006; 20: 129–144. DOI: 10.1080/02678370600856615

- Lambeek LC, van Mechelen W, Knol DL, Loisel P, Anema JR. Randomised controlled trial of integrated care to reduce disability from chronic low back pain in working and private life. BMJ 2010; 340: c1035. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.c1035

- Gismervik S, Aasdahl L, Vasseljen O, Fors EA, Rise MB, Johnsen R, et al. Inpatient multimodal occupational rehabilitation reduces sickness absence among individuals with musculoskeletal and common mental health disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Scand J Work Environ Health 2020; 46: 364–372. DOI: 10.5271/sjweh.3882

- WONCA Classification Committee, Committee WC. International Classification of Primary Care, Second Edition (ICPC-2). Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994; 23: 129–138.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002; 52: 69–77. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

- Nguyen QC, Osypuk TL, Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ. Practical guidance for conducting mediation analysis with multiple mediators using inverse odds ratio weighting. Am J Epidemiol 2015; 181: 349–356. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwu278.

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008; 40: 879–891. DOI: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879

- van Vilsteren M, van Oostrom SH, de Vet HC, Franche RL, Boot CR, Anema JR. Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 10: CD006955. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006955.pub3

- Venning A, Oswald TK, Stevenson J, Tepper N, Azadi L, Lawn S, et al. Determining what constitutes an effective psychosocial ‘return to work’ intervention: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2021; 21: 2164. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-021-11898-z.

- Verhoef JA, Bal MI, Roelofs PD, Borghouts JA, Roebroeck ME, Miedema HS. Effectiveness and characteristics of interventions to improve work participation in adults with chronic physical conditions: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2022; 44: 1007–1022.

- Staal JB, Hlobil H, van Tulder MW, Köke A, Smid T, van Mechelen W. Return-to-work interventions for low back pain: a descriptive review of contents and concepts of working mechanisms. Sports Medicine (Auckland, NZ) 2002; 32: 251–267.

- Øverland S, Grasdal AL, Reme SE. Long-term effects on income and sickness benefits after work-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy and individual job support: a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 2018; 75: 703–708.

- Valeri L, Coull BA. Estimating causal contrasts involving intermediate variables in the presence of selection bias. Stat Med 2016; 35: 4779–4793.