ORIGINAL REPORT

SEX AND AGE GROUP FOCUS ON OUTCOMES AFTER MULTIMODAL REHABILITATION FOR PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC PAIN IN NORTHERN SWEDEN

Linda SPINORD, OT, PhD1,3, Gunilla STENBERG, PT, PhD1, Ann-Charlotte KASSBERG, OT, PhD2,3 and Britt-Marie STÅLNACKE, MD, Phd1

From the 1Department of Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Umeå University, Umeå, 2Department of Health Science, Luleå University of Technology and 3Department of Development and Research, Region Norrbotten, Luleå, Sweden

Objectives: To investigate the outcomes of a multimodal rehabilitation programme (MMRP) regarding pain intensity, emotional functioning, activity and physical functioning, social response, and health, with regard to sex and age.

Methods: This retrospective longitudinal study was based on data from patients at 2 specialist pain clinics in northern Sweden immediately after MMRP (short-term) and at 1-year follow-up (long-term). Data from 439 patients were analysed according to sex and to age groups 18–30, 31–45 and 46–65 years.

Results: The men improved with larger effect sizes (ESs) than women immediately after MMRP. The youngest age group showed improvements with greater ESs compared with the older age groups, both in the short and long term. Social support decreased for both women and men and in all 3 age groups in the long term. Improvements in both the short and long term were found in pain intensity, emotional functioning, and activity and physical functioning, in both women and men, as well as the different age groups.

Conclusion: Both women and men with chronic pain, and from all of the different age groups, benefitted from MRRP. Since improvements for men were not sustained over time, they may need further support after the programme.

LAY ABSTRACT

This study aimed to determine the outcomes of a multimodal rehabilitation programme in sex and age groups regarding pain intensity, emotional functioning, activity and physical functioning, social response, and health. Data from 439 patients from 2 specialist pain clinics in northern Sweden were analysed according to sex and age groups 18–30, 31–45 and 46–65 years. Improvements were found in both women and men and in all age groups, in both the short and long term, regarding pain intensity, emotional functioning, and activity and physical functioning. Improvements among the men did not sustain over time to the same extent as for women. This study shows that men, women and the 3 age groups improve, both in short and long term, after a multimodal pain rehabilitation programme.

Key words: sex; men; pain rehabilitation; Swedish Quality Registry of Pain; women.

Citation: J Rehabil Med 2022; 54: jrm00333. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v54.2336

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Aug 12, 2022; Epub ahead of print: Sep 13, 2022; Published: Nov 1, 2022

Correspondence address: Linda Spinord , Department of Reasearch and Development, Region Norrbotten and Department of Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Umeå University, Rehabilitation Medicin, SE 90187 Umeå Sweden. E-mail: linda.spinord@norrbotten.se

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

Chronic pain (i.e. pain duration >3 months) (1) is a complex and multifaceted condition. In addition, chronic pain causes major health problems and a is socio-economic burden on the individual and on society. Approximately 20% of the population of Europe report moderate to severe intensity of pain (2). A chronic pain condition is influenced by physical, psychological, emotional and social factors, and affects individuals in many different aspects in life (3, 4). People experiencing chronic pain describe several impairments due to pain, for example, sleep problems, limitations when performing everyday activities, a limited ability to work and to participate in different social contexts (5).

Since chronic pain is a complex process, the use of a biopsychosocial model is recommended in clinical practice for its treatment (6, 7). The model emphasizes the common interactions between all the factors that impact people’s perceptions of their overall health. Nowadays, a multifactorial approach based on the biopsychosocial model is applied in multimodal rehabilitation programmes (MMRPs) for patients with chronic pain. An MMRP is based on a holistic perspective, which focuses on the whole person. MMRPs are administrated over the course of several weeks in group settings by different health professionals, and are usually based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (8, 9). The programmes combine physiological, pedagogical and physical interventions, such as pain education and physical activity coordinated by an interdisciplinary team (10, 11). According to several systematic reviews, MMRP is a more effective method of treatment for complex chronic pain conditions, both on a general level and for specific outcomes, such as activity level, perceived pain and function, compared with single treatment/unimodal interventions (9, 10, 12). Therefore, people with chronic pain should be referred to MMRP when individual interventions do not lead to notable improvements.

In Sweden, approximately 2,700 adult patients participate in MMRPs annually in specialist care (13). The extent to which people can benefit from pain rehabilitation varies from person to person and can also vary depending on the person’s age and situation in life. Currently, little is known about how rehabilitation outcomes vary among different age categories. A larger proportion of women than men report chronic pain (13, 14) and, in Sweden, a higher proportion of women participate in MMRP. No sex-based studies have been done in this particular field and there is a need for research that investigates whether women and men have different or similar outcomes after MMRP (15) and the reasons for any differences.

It is well known that the prevalence of chronic pain increases with age (13). Most of the patients who participate in MMRPs are adults aged 18–65 years and, in a previous study (16), it was shown that all age groups in this age span improved at 1-year follow-up after MMRP. However, the patterns of improved variables differed in the age groups in terms of physical function, health, and emotional function. Yet, there is limited knowledge about when the improvements occur in terms of short- and long-term outcomes.

On account of the knowledge gaps described above, it was decided to carry out a follow-up study of patients participating in MMRP. The aim of this study was to investigate outcomes immediately after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up, regarding pain, emotional functioning, activity and physical functioning, social factors, and health domains in women and men and in 3 different age groups.

METHODS

Design/setting

The MMRP in this study involved a multi-professional team with a physician, physiotherapist, psychologist, occupational therapist, social worker and nurse. The patient and the team drew up a rehabilitation plan in collaboration and the patients were encouraged to take an active role in goal setting. General goals for the MMRP were improved activity levels and life satisfaction, as well as the development of coping strategies that support patients in their achievement of individual goals. The interventions included in the MMRP were exercises, body awareness, activity training, ergonomic practice, occupational strategies, and information about psychological reactions to chronic pain. The MMRP lasted 4–5 weeks, 4–5 days a week and approximately 6 h per day. The majority of the interventions were conducted in group sessions. A variation of interventions could be offered, based on individual needs. Since a more detailed description of the MMRP has been given in previous publications (16), only a brief account is given here.

Procedure/patients

A longitudinal retrospective study design was used to investigate the outcomes of MMRP from both short- and long-term perspectives in specialist care. The short perspective was measured from start to immediately after MMRP, while the long perspective was measured from start to 1-year follow-up of MMRP and from immediately after MMRP to 1-year follow up. This study was performed at 2 pain specialist clinics in northern Sweden (Pain Rehabilitation Clinic, Umeå University Hospital and the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Sunderby County Hospital) during 2011–15. The patients were divided into 3 age groups: 18–30, 31–45 and 46–65 years.

The inclusion criteria for MMRP were: (i) disabling non-malignant musculoskeletal pain >3 months, (ii) age between 18 and 65 years, and (iii) prerequisite of coordinated interventions from several professions, in need of assistance to be able to develop coping strategies, able to work or assessed to be able to return to work, and able to benefit from receiving group rehabilitation. Exclusion criteria were: (i) ongoing major somatic or psychiatric disease, such as heart disease, cancer, schizophrenia or deep depression, and (ii) substance abuse e.g. of alcohol, narcotics or medication. The majority of the patients had been referred to specialist care by a primary healthcare facility.

Instruments

Swedish Quality Registry of Pain. The SQRP (13) is a national registry recognized by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. The SQRP contains data based on patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) at start of MMRP, immediately after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up after completed MMRP. The included questionnaires covered descriptive variables about the participant’s background, pain characteristics, activity/participation, psychosocial factors, and health-related quality of life.

Multidimensional Pain Inventory. The MPI is a self-reported instrument that measures psychosocial, cognitive and behavioural experiences of chronic pain. The instrument consists of 3 parts. The first part is about how pain affects an individual’s life. It consists of 5 subscales: 1: pain severity (MPI-pain-severity); 2: life interference (MPI-pain-interfer); 3: life control (MPI-lifcon); 4: affective distress (MPI-distress); and 5: social support (MPI-socsupp). The second part measures the responses given by significant others and consists of 3 subscales: 1: punishing reactions (MPI-punish); 2: solicitous reactions (MPI-solict); and 3: distraction reactions (MPI-distract). Part 3 covers the frequency of participation in different daily occupations: 1: household chores; 2: outdoor work; 3: activities outside the home; and 4: social activities. These 4 subscales are combined into a composite scale, the general activity index (MPI-gai), which was used in the present study. The patients responded on a 7-point scale (range 0–6). Higher scores indicate greater frequency of occurrence (17).

Short Form Health Survey. The SF-36 investigates conditions and limitations in daily life, including levels of well-being and personal evaluations of health. The instrument consists of 36 questions about 8 dimensions which are reported using a scale of 0–100. Higher scores reflect better self-reported health status. The 8 domains are physical functioning (SF36-pf), role-physical (SF36-rp), bodily pain (SF36-bp), general health (SF36-gh), vitality (SF36-vt), social functioning (SF36-sf), role-emotional (SF36-re), and mental health (SF36-mh). Based on the 8 dimensions, a physical component summary and mental component summary are calculated (18). All 8 dimensions were used for this study.

Numerical Pain Rating Scale. The NPRS measures mean pain intensity during the last week on a numerical rating scale between 0 and 10, where 0 represents no pain and 10 represents worst possible pain (19).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The HADS is a self-reported assessment that measures anxiety and depression. The questionnaire consists of 14 items divided into 2 subscales: anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D). The scale for each subscale ranges between 0 and 21. A higher score in each subscale indicates a higher risk of depression and anxiety (20).

Domains

The instruments were categorized into 5 domains: pain intensity (MPI-pain-severity, SF36-bp, NPRS), emotional functioning (MPI-distress, SF36-vt SF36-mh, HADS-A, HADS-D), activity and physical functioning (MPI-pain-interfer, MPI-lifcon, MPI-gai, SF36-sf, SF36-rp, SF36-re, SF36-pf), social response (MPI-socsupp, MPI-punish, MPI-solict, MPI-distract) and health (SF36-gh), mainly according to the recommendation of the Initiative on Methods, Measurement (IMMPACT), and Validation and Application of Patient-relevant core set of outcome domains to assess multimodal pain therapy (VAPAIN) (21). The results were reported in domains and the current variables in parentheses.

Data collection

The patients filled in questionnaires based on SQRP at start of MMRP, immediately after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up after completed MMRP. The questionnaires were distributed to the patients by post before MMRP and at 1-year follow-up. The questionnaires immediately after MMRP were distributed at the clinic. A reminder was sent if no answer was received after 4 weeks at the 1-year follow-up.

Drop-outs

Of the 439 patients who answered the questionnaires at start of MMRP, 431 (96%) answered the questionnaires immediately after MMRP and 292 patients (67%) answered at 1-year follow-up (Fig. 1). Significant differences at start of MMRP were found between the responders at 1-year follow-up and the non-responders. The responders reported significantly better physical and mental health than the non-responders (HADS A p = 0.023, MPI-distress p = 0.021, SF-36RE p = 0.011, SF36-mh p = 0.003). Women had a higher response rate than men at 1-year follow-up (68% vs 59%). The oldest age group 46–65 years had a higher response rate (79%) than the younger age groups (18–30 years, 56% and 31–45 years, 58%).

Fig. 1. Flow chart for patients included in this study. MMRP: multimodal rehabilitation programme.

When comparing responders vs non-responders in the separate groups (sex and age) at start of MMRP, we found that patients who did not complete the 1-year follow-up reported significantly lower mental health (SF36-mh) (p < 0.05) compared with those who completed the follow-up. This was not found in the 31–45 years age group.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, Sweden (Dnr 2015/240-31).

Data analysis

To compare women and men, χ2, Mann–Whitney and Student’s t-test were performed. The data are presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR) and means with standard deviations (SD). Categorical variables are presented in numbers and percentages. For all PROM, non-parametric tests were used. The changes between start and immediately after MMRP vs 1-year follow-up, and between start of MMRP and 1-year follow-up were tested with Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. Results with p-value < 0.05 (2-sided) were considered statistically significant for all tests. Effect size (ES) was calculated for the significant changes between start and immediately after MMRP vs 1-year follow-up and between start of MMRP and 1-year follow-up. ESs were calculated (r = z/square root of N) and assessed against Cohen’s (1988) criteria (0.10 small, 0.30 medium, 0.5 large) (22). Comparisons between age groups were conducted by using χ2, Kruskal–Wallis and 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (with a post-hoc test if there were significant differences). Missing data were not replaced for the descriptive statistics. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software version 26 (Armok, NY).

RESULTS

Patients at start of MMRP

In total, 439 patients completed the questionnaires in SQRP at start of MMRP. The majority of the patients were women (82%) and most patients were born in Sweden (94%). More than half (54%) of the patients had had persistent pain for 5 years or more (mean 4 years, SD 7 years). A higher percentage of the women had a university degree compared with men, and women reported a higher number of pain sites than did the men (p ≤ 0.001). Demographic variables are reported in Table I for women and men and the 3 age groups.

A comparison of women’s and men’s characteristics at start of MMRP showed that women reported significantly higher general activity on the MPI-gai (p = 0.043, ES 0.07) than men (Table II).

| Women n = 356 | Men n = 83 | p-value | 18–30 years n = 65 | 31–45 years n = 186 | 46–65 years n = 184 | p-value | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Pain intensity | ||||||||||||

| Pain Severity (MPI-Pain-severity) | 4.33 (1) | 4.39 (0.1) | 4.33 (1.33) | 4.31 (0.9) | 0.471 | 4.67 (1.33) | 4.47 (0.82) | 4.33 (1) | 4.37 (0.81) | 4.33 (1.33) | 4.35 (0.82) | 0.607 |

| Bodily Pain (SF36-bp) | 22 (11) | 24 (13) | 22 (19) | 23 (12) | 0.208 | 22 (20) | 22 (13) | 22 (11) | 24 (13) | 22 (10) | 24 (12) | 0.531 |

| Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) | 7 (2) | 6.89 (1.5) | 7 (3) | 6.5 (1.6) | 0.055 | 7 (7) | 7 (1.4) | 7 (2) | 7 (2) | 7 (2) | 7 (1.4) | 0.866 |

| Emotional functioning | ||||||||||||

| Affective Distress (MPI-Distress) | 3.33 (1.67) | 3.25 (1.27) | 3.33 (1.33) | 3.26 (1.09) | 0.768 | 3.84 (1.66) | 3.58 (1.15) | 3.5 (1.33) | 3.38 (1.18) | 3 (1.67) | 3.02 (1.27) | 0.002b,c |

| Life control (MPI-LifCon) | 2.75 (1.25) | 2.87 (1) | 2.75 (1.25) | 2.77 (1.15) | 0.386 | 2.67 (1.5) | 2.59 (1.08) | 2.75 (1.5) | 2.80 (1.03) | 3 (1) | 2.98 (1.01) | 0.025b |

| Vitality (SF36-vt) | 20 (25) | 21 (17) | 20 (25) | 24 (19) | 0.297 | 25 (25) | 24 (17) | 15 (24) | 20 (16) | 20 (25) | 23 (19) | 0.133 |

| Mental health (SF36-mh) | 60 (28) | 62 (19) | 60 (28) | 59 (19) | 0.287 | 56 (27) | 56 (18) | 60 (24) | 60 (18) | 68 (25) | 64 (19) | 0.001b,c |

| Anxiety (HADS-A) | 7.5 (7) | 7.7 (4.6) | 8 (5.5) | 7.6 (4) | 0.991 | 10 (7) | 9 (5) | 8 (6) | 8 (4) | 7 (7) | 7 (4) | < 0.001b,c |

| Depression (HADS-D) | 8 (5) | 7.7 (4) | 8 (6.25) | 8 (3.8) | 0.215 | 8 (6) | 8 (4) | 8 (5) | 8 (4) | 7 (7) | 8 (4) | 0.075 |

| Activity and physical functioning | ||||||||||||

| Life interference (MPI-Pain-interfer) | 4.55 (1.2) | 4.45 (1) | 4.82 (1.18) | 4.6 (0.85) | 0.146 | 4.6 (1.19) | 4.52 (0.89) | 4.6 (1.18) | 4.50 (0.87) | 4.58 (1.3) | 4.43 (0.92) | 0.742 |

| General activity index (MPI-GAI) | 2.54 (1.01) | 2.54 (0.74) | 2.29 (1.12) | 2.38 (0.89) | 0.043 | 2.45 (1.11) | 2.45 (0.80) | 2.48 (0.96) | 2.49 (0.72) | 2.55 (1.09) | 2.55 (0.81) | 0.650 |

| Social functioning (SF36-sf) | 50 (38) | 48 (24) | 50 (38) | 48 (24) | 0.989 | 50 (35) | 45 (23) | 50 (38) | 47 (22) | 50 (38) | 50 (25) | 0.284 |

| Role physical (SF36-rp) | 0 (25) | 11 (21) | 0 (25) | 10 (19) | 0.944 | 0 (25) | 10 (18) | 0 (0) | 9 (19) | 0 (25) | 11 (23) | 0.721 |

| Role emotional (SF36-re) | 67 (100) | 52 (42) | 33 (100) | 49 (44) | 0.517 | 67 100) | 52 (43) | 33 (100) | 52 (40) | 67 (100) | 52 (44) | 0.989 |

| Physical functioning (SF36-pf) | 55 (25) | 52 (20) | 55 (30) | 55 (21) | 0.297 | 60 (35) | 57 (35) | 55 (30) | 55 (20) | 50 (30) | 49 (20) | 0.012c |

| Social response | ||||||||||||

| Social support (MPI-Socsupp) | 4 (2) | 4.05 (1.25) | 4.5 (1.66) | 4.29 (1.27) | 0.067 | 4.33 (1.33) | 4.25 (4.33) | 4 (1.67) | 4.02 (1.22) | 4.33 (1.33) | 4.12 (1.35) | 0.396 |

| Punishing response (MPI-Punish) | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.67 (1.3) | 1.75 (1.62) | 1.71 (1.19 | 0.499 | 1.25 (1.75) | 1.63 (1.38) | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.78 (1.31) | 1.33 (1.33) | 1.59 (0.5) | 0.328 |

| Solicitous response (MPI-Solict) | 2.83 (2) | 2.88 (1.28) | 3 (1.54) | 2.89 (1.23) | 0.783 | 3.17 (1.66) | 3.09 (1.17) | 2.83 (2.08) | 2.80 (1.38) | 2.83 (1.88) | 2.89 (1.39) | 0.318 |

| Distracting response (MPI-Distract) | 2.49 (1.5) | 2.48 (1.16) | 2.5 (1.81) | 2.53 (1.07) | 0.65 | 3 (1.25) | 2.93 (1.05 | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.39 (1.10) | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.46 (1.18) | 0.004a,b |

| Health | ||||||||||||

| General health (SF36-gh) | 40 (25) | 42 (19) | 35 (17) | 39 (20) | 0.134 | 31 (31) | 41 (22) | 35 (20) | 40 (19) | 40 (25) | 43 (19) | 0.263 |

| IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; MPI: Multidimensional Pain Inventory; SF-36: Short Form health survey; NPRS: numerical rating pain scale; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. To compare women and men, Mann–Whitney was used and to compare age groups, Kruskal–Wallis test was used; apost hoc test showed significant difference between 18–30 years and 31–45 years age groups; bpost hoc test showed significant difference between 18-30 years and 46–65 years age groups; cpost hoc test showed significant difference between 31–45 years and 46–65 years age groups; p < 0.05 presented in bold. | ||||||||||||

A comparison of the age groups at start of MMRP showed that the youngest age group (18–30 years) reported significantly higher scores on distraction response (MPI-distract) than the older age groups (vs 31–45 years p = 0.003; 46–65 years p = 0.017) and lower scores on life control (MPI-lifcon) than the age group 46–65 years (p = 0.03). The oldest age group (46–65 years) reported significantly lower scores on physical functioning (SF36-pf) than the age group 31–45 years (p = 0.035), higher scores on mental health (SF36-mh) (vs the age group18–30 years p = 0.001 and age group 31–45 years p = 0.021) and lower scores on emotional functioning (MPI-distress) (vs 18–30 years p = 0.006 and 31–45 years p = 0.021); HADS-A (vs18–30 p ≤ 0.001, 31–45 years p = 0.038) than the younger age groups (Table II).

Outcomes for women immediately after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up

During the MMRP (between start and immediately after), all variables in the domains pain intensity and emotional functioning and 2 variables in activity and physical functioning (MPI-pain-interfer, MPI-gai) improved significantly with small to medium ESs for women.

For those who answered the questionnaire, these improvements persisted after 1 year with the exception of general activity index (MPI-gai) (small to medium ES).

In addition to these, physical functioning (SF36-pf) and general health (SF36-gh) (small ESs) were improved and social support (MPI-socsupp) and punishing response (MPI-punish) decreased (small ESs) between after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up. For details, see Table III.

Outcomes for men immediately after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up

Immediately after MMRP, the results for men showed significant improvements with medium ESs on all variables in pain intensity and emotional functioning, except for HADS-A (small ES). Small ESs were also found in health and in 3 of the variables in activity and physical functioning (MPI-pain-interfer, MPI-gai, SF36-sf).

Of the 13 variables, which showed improvement immediately after MMRP, only the following variables continued to show improvement (small ESs) at 1-year follow-up: pain intensity (SF36-bp, NPRS), depression (HADS-D) and 1 activity and physical functioning variable (MPI-pain-interfer).

Several outcomes deteriorated significantly between after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up: pain intensity (MPI-pain-severity) and emotional functioning (MPI-distress, MPI-lifcon, SF36-vt, SF36-mh) (Table IV).

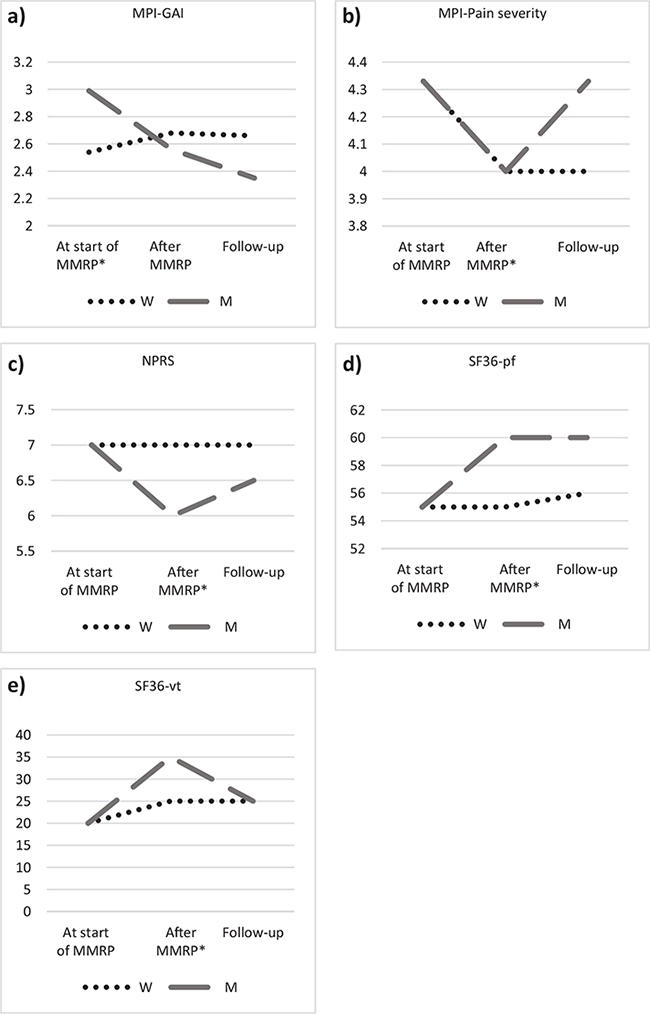

A few significant differences were found between women and men for 1 or more of the 3 time-points (i.e. start of MMRP, immediately after MMRP and 1-year follow-up). The variables that were found to differ between women and men are shown in Fig. 2a–d.

Fig. 2a–e. (a) Differences between women and men at the 3 time-points; (a) MPI-GAI: General activity index, (b) MPI-Pain severity: Pain severity (c) NPRS: numerical rating pain scale; (d) SF36-pf: Physical functioning (e) SF36-vt: Vitality; *Significant differences between men and women.

Results for age groups immediately after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up

During the MMRP (between start and immediately after), the analysis for the youngest age group (18–30 years) showed significant improvements with medium ESs in pain intensity (MPI-pain-severity, SF36-bp), and in emotional functioning (MPI-distress, MPI-lifcon SF36-mh). Small ESs were found in pain intensity (NPRS), emotional functioning (SF36-vt, HADS-D), social functioning (SF36-sf) and in health.

For those who answered the questionnaire, the improvements persisted 1 year after MMRP, with the exception of social functioning (SF36-sf).

In addition to these, life interference (MPI-Pain-Inter) and physical functioning (SF-36-pf) were improved with medium ESs between the end of the programme and 1-year later. For details, see Table V.

During the MMRP (between start and immediately after), the results for the age group 31–45 years showed significant improvements with medium ESs in 1 variable in pain intensity domain (SF36-bp) and 1 in emotional functioning domain (MPI-distress). There were small ESs in the rest of the variables in pain intensity and emotional functioning domains, and in 3 variables (MPI-Pain-interfer, MPI-gai and SF36-rp) in the domain activity and physical functioning.

For those who answered the questionnaire, these improvements persisted after 1 year with the exception of affective distress (MPI-distress) (medium to small ES), anxiety (HADS-A) and general activity index (MPI-gai). For details, see Table VI.

During the MMRP (between the start and immediately after MMRP), significant improvements with medium ESs were shown in the oldest age group (46–65 years) in 3 variables in the emotional functioning domain (MPI-distress, MPI-lifcon, SF36-vt). Small ESs were found in all pain intensity variables and in activity and physical functioning (MPI-pain-interfer, MPI-gai, SF36-re).

For those who answered the questionnaire, these improvements persisted after 1 year, with the exceptions of general activity index (MPI-gai) and role emotional (SF-36-re).

In addition to these, physical functioning (SF36-pf) (small effect size) was improved between the end of the programme and 1-year after. For details, see Table VII.

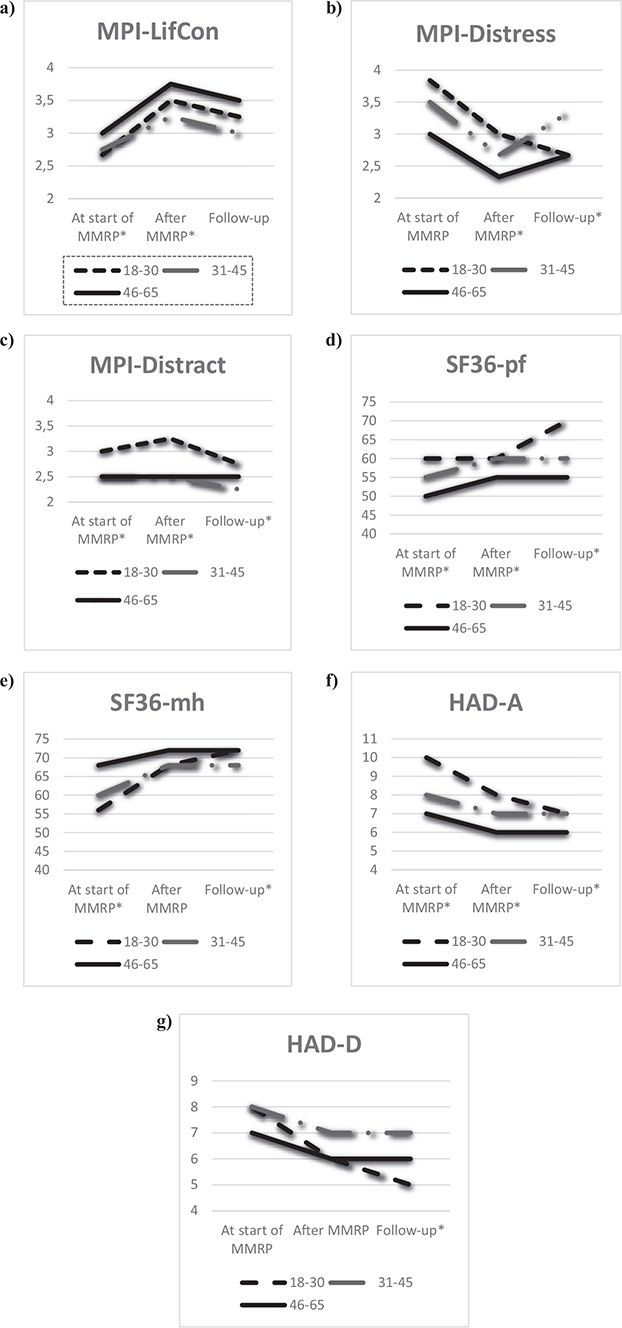

A few significant differences were found between the age groups at the 3 time-points (i.e. at the start of MMRP, immediately after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up). The variables that differed significantly are illustrated in Fig. 3a–g.

Fig. 3a–g. Estimated medians in Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI), Short Form Health Survey (SF36), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD). (a) ): MPI-LifCon: Life Control, (b) MPI-Distress: Affective distress, (c) MPI-Distract: Distracting response, (d) : SF36-pf: physical functioning, (e) SF36-mh: mental health, (f) HAD-A: Anxiety, (g) HAD-D: Depression, in the 3 age groups before multimodal rehabilitation programme (MMRP), immediately after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up, *Significant differences.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the short- and long-term outcomes after MMRP for women and men with chronic pain were evaluated using PROM immediately after MMRP and at follow-up after 1 year. Three age groups were studied separately. The outcome variables improved gradually throughout the follow-up period and the improvement persisted after 1 year to a greater extent for women than for men. In all age groups, pain intensity and emotional functioning improved with similar changes at both short and long term, while activity and physical functioning improved to a lesser extent in the youngest age group. Social support decreased significantly for both women and men, as well as for the age groups at 1-year follow-up.

There are conflicting results in the literature regarding whether MMRP is more effective for women than for men with chronic pain. Some research findings indicate that women benefit more than men from MMRP (16, 23, 24), while other findings show that men benefit more in some variables after MMRP than women (25). Other studies show no difference regarding women and men’s outcomes after MMRP (26, 27). In this study, it was shown that both women and men benefited from MMRP, but the improvements were in different phases. Nonetheless, the women included were found to have more persistent improvement throughout the period from before MMRP to 1-year follow-up and they improved in more domains than the men. Men improved most during the programme, but their improvements were not stable at 1-year follow-up to the same extent as in women. Our results of reduced pain in all pain variables over time in women and in men for MPI-pain severity, both after MMRP and at 1-year follow-up, seem to be in accordance with another study of chronic lower back pain (28), which also reported reduced pain intensity for women and men at these time-points (28). Even though the content of MMRP does not include pain-reducing treatment per se, the programme’s biopsychological approach seems to affect the patients’ pain experience in a positive way.

In the current study, women improved to a greater extent than men in all variables in emotional functioning, and the results were sustained at 1-year follow-up. For men, only depression improved during MMRP and this improvement was sustained at 1-year follow-up. Similar results of reduced depression after the rehabilitation programme in both women and men have been reported in 2 previous studies, but in contrast to the current study, improvement over 12 months was found only in women (23, 28). According to the results of qualitative studies about experiences from chronic pain rehabilitation, there are similarities between women’s and men’s narratives (29, 30). Furthermore, Ahlsen et al. found that narratives from patients with chronic pain are both individually and culturally formed (31). That means that patients are influenced, to a greater or lesser extent, by stereotype gender norms when talking about pain, answering questions and in pain behaviour (32). These stereotype gender norms can affect assessment, treatment and rehabilitation and may be an explanation as to why women and men partly report different outcomes after rehabilitation. In addition, stereotyped gender notions and expectations among professionals regarding their patients in MMRP (33) may influence the design of the rehabilitation and in the long-term may affect the results. It is important for future studies to examine which interventions and support are needed after the end of a programme to improve the long-term results for men to the same extent as for women after MMRP.

Since MMRP has a holistic perspective, it seems to be of importance to also consider social relationships together with other outcomes after MMRP. Patients with chronic pain live in a social context that includes social relationships with others. These aspects are highly relevant, and therefore social support and perceived responses from significant others were measured by MPI in the current study. We found that women reported significantly lower scores for social support and increased punishing response after MMRP and at the 1-year follow-up. Interestingly, the men’s pattern was found to be different: they reported significantly lower scores for social support after the MMRP compared with at the start, and that result persisted to 1-year follow-up. These findings of decreased social support after MMRP have also been shown in some other studies (34). This result might be interpreted as family members having less concern after the patient has participated in the programme and then become more independent. Furthermore, in a previous qualitative study, we found that knowledge acquired by patients participating in MMRP and discussions with other patients in similar situations gave rise to increased self-esteem and insight into their own importance and self-worth. This led to different behaviour and a reduced need for support from significant others (30).

Another finding in of the current study was that the perceptions of solicitous response were lower at 1-year follow-up than at start for both women and men. Previous research has shown that solicitous actions from family/spouses in terms of taking over the participant’s duties or encouraging rest may lead to maintaining pain behaviours such as avoidance of pain (35). In addition, avoidance of pain could lead to a negative downward spiral that fuels negative pain-related outcomes (36). Previous research has shown that social influences can play a role in patient’s engagement in activity with pain present and the willingness to have pain without trying to avoid and control it (35). With that in mind, a reduction in perceived solicitous actions from the family/spouses is of benefit for the participants’ pain rehabilitation. In the current study, the oldest age group (45–65 years) reported lower physical functioning and better mental health than the 2 younger age groups at start of MMRP. This could be explained by previous research that has reported that physical functioning decreases and mental health and health-related quality of life increase with age (37). In addition, it has been shown that older individuals with pain report better health and quality of life than younger individuals with chronic pain, while younger individuals report more emotional difficulties (38).

Although all the 3 age groups in the current study were found to benefit from MMRP, the improvements were shown during different phases for the 3 age groups. All age groups improved in pain severity and in the youngest age group (18–30 years), pain severity decreased more than it did in the other age groups. In contrast to the current findings, in a study conducted in southern Sweden, Person et al. (2012) found that younger patients (< 40 years) had a high risk for deterioration on the pain severity scale 1 year after MMRP (38). One reason for this disparity could be the different study populations with a higher percentage of patients with a university degree and born in a Nordic country in the current study.

Additional findings from the current study were that the youngest age group (18–30 years) showed several significant improvements with medium ESs in both the short and long term after MMRP. The youngest age group also reported reduced social support which might be an effect of the positive results with lower pain intensity, lower affective distress, better mental health and more life control. These factors may have contributed to a process of achieving autonomy since late adolescence and early adulthood is a period in life that is marked by the occurrence of neurobiological, psychological and behavioural changes, attainment of societal milestones and adjustment to contextual life changes (39).

Methodological considerations

Some limitations of this study should be noted. The fact that the patients in this study were referred to specialist clinics in northern Sweden and represented a selected group of severe cases of patients with complex consequences of chronic pain makes it difficult to generalize our results to all persons with chronic pain. Since this study is based on a registry of real-world practice, the possibility of having a control group or treatment as usual is limited and ethically complicated. The lack of a control group and comparative treatment might also influence our interpretation of the results in this study. However, the study was conducted in accordance with previous research and a large number of national studies based on the SQRP (11, 13). Even though the study has a retrospective design, the patients were included at the start of participating in MMRP and followed longitudinally from start to immediately after MMRP and to 1-year follow-up. In some previous studies with similar clinical setting this has been seen as a prospective design (40). The strengths of this study are that all instruments are widely used and have shown good validity. The outcome variables are in agreement with the biopsychosocial model and IMMPACT as well as the VAPIAN (21). Furthermore, a total population of patients participating in MMRP at the 2 specialist pain clinics was included, and outcomes were measured both after the programme and at 1-year follow-up. It is possible that the dropouts immediately after MMRP to 1-year follow-up may have influenced the long-term results since the drop-out rates were relatively high.

CONCLUSION

These results show that women, men and all the different age groups benefitted from MMRP. Since men’s improvement did not sustain over time, this indicates that men might need further support after MMRP. Social support was found to decrease in the long term for women, men and all the age groups. It is important to involve family members and/or significant others in the rehabilitation process, for instance, in the setting of common goals. This could increase the support given to the patient to cope with everyday life. The current findings can contribute to increased knowledge of differences and similarities in different subgroups participating in MMRP, which could be useful for the further development of MMRP in order to achieve sustainable results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the County Councils of Norrbotten and Västerbotten.

REFERENCES

- Nicholas, M., Vlaeyen, J. W., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Benoliel, R. et al (2019). The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain, 160(1), 28-37.

- Breivik, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen, R, Gallacher, D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006; 5: 287–333.

- Linton SJ, Shaw WS. Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Phys Ther 2011; 91: 700–711.

- Gatchel RJ. The biopsychosocial model of chronic pain. Clin Insights: Chronic Pain 2013; 2013: 5–17.

- Andersen LN, Kohberg M, Juul-Kristensen B, Herorg L, Sögaard K, Kaya-Roessler, K. Psychosocial aspects of everyday life with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Scand J Pain 2014; 5: 131–148.

- Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017; 158(Suppl 1): S11–S18.

- Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Amer Psychol 2014; 69: 119.

- Bennett MI, Closs SJ. Methodological issues in nonpharmacological trials for chronic pain. Anaesth Pain Intens Care 2011; 15: 126–132.

- SBU (The Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment in Health Care, Rehabilitation for chronic pain. SBU report Vol. no 198/2010). Stockholm: Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (in Swedish).

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, Smeets RJEM, Ostelo RWJG, Guzman J, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015; 350: h444.

- Fischer-Riviano M, Schults ML, Stålnacke BM, Ekholm J, Persson EB, Lövgren M. Variability in patient characteristics and service provision of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation: a study using? the Swedish National Quality Registry for Pain Rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med 2020; 52: 1–10.

- Gerdle B, Rivano Fischer M; Ringqvist Å. Interdiciplinary pain rehabilitation programs: evidence and clinical real-world. In: Pain management – from pain mechanisms to patient care. [accessed 2020 July 05]. Available from DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.102411.

- SQRP. Swedish Quality Registry for Pain Rehabiltation (in Swedish: Nationella Registret över smärtrehabilitering, NRS). Available from: http//:www.ucr.uu.se/nrs/

- Wijnhoven HA, de Vet HC, Picavet HSJ. Explaining sex differences in chronic musculoskeletal pain in a general population. Pain 2006; 124: 158–166.

- SBU (The Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment in Health Care, Treatment of Long-Term Pain States. Focusing on Women. SBU report Vol-no301/2019). Stockholm: Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (in Swedish).

- Spinord L, Kassberg A-C, Stenberg G, Sålnacke B-M. Comparison of two multimodal pain rehabilitation programmes, in rela-tion to sex and age. J Rehabil Med 2018; 50: 619–628.

- Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI). Pain 1985; 23: 345–356.

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware Jr JE. The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey—I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Social Sci Med 1995; 41: 1349–1358.

- Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain 2011; 152: 2399–2404.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370.

- Kaiser U, Kopkow C, Deckert S, Neustadt K, Jacobi L,Cameon L, et al. Developing a core outcome domain set to assessing effectiveness of interdisciplinary multimodal pain therapy: the VAPAIN consensus statement on core outcome domains. Pain 2018; 159: 673–683.

- Lenhard W. Lenhard A. 2016. Calculation of effect sizes. [accessed 2020 Nov]. Available from: https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html. Dettelbach (Germany):Psycometrica. DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.17823.92329.

- Racine M, Solé E, Sánchez- Rodríguez E, Tomé-Pires C, Roy R, Jensen MP, et al. An evaluation of sex differences in patients with chronic pain undergoing an interdisciplinary pain treatment program. Pain Practice 2020; 20: 62–74.

- Pietilä-Holmner E, Enthoven P, Gerdle B, Molander P, Stålnacke BM. Long-term outcomes of multimodal rehabilitation in primary care for patients with chronic pain. J Rehabil Med 2020; 52: 1–10.

- Hooten WM, Townsend CO, Decker PA. Gender differences among patients with fibromyalgia undergoing multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation. Pain Med 2007; 8: 624–632.

- Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology 2008; 47: 670–678.

- Keogh E, McCracken LM, Eccleston C. Do men and women differ in their response to interdisciplinary chronic pain management? Pain 2005; 114: 37–46.

- Gagnon S, Lensel-Corbeil G, Duquesnoy B. Multicenter multidisciplinary training program for chronic low back pain: French experience of the Renodos back pain network (Réseau Nord-Pas-de-Calais du DOS). Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2009; 52: 3–16.

- Ahlsen B, Bondevik H, Mengshoel AM, Solbrække KN. (Un) doing gender in a rehabilitation context: a narrative analysis of gender and self in stories of chronic muscle pain. Disabil Rehabil 2014; 36: 359–366.

- Spinord L, Kassberg A-C, Stålnacke B-M, Stenberg G. Finding self-worth—Experiences during a multimodal rehabilitation program when living at a residency away from home. Can J Pain 2020; 4: 237–246.

- Ahlsen B, Mengshoel AM, Solbrække KN. Troubled bodies – troubled men: a narrative analysis of men’s stories of chronic muscle pain. Disabil Rehabil 2012; 34: 1765–1773.

- Stenberg G, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Ahlgren C. “Getting confirmation”: gender in expectations and experiences of healthcare for neck or back patients. J Rehabil Med 2012; 44: 163–171.

- Lehti A, Fjellman- Wiklund A, Stålnacke BM, Hammarström A, Wiklund M. Walking down ‘Via Dolorosa’ from primary health care to the specialty pain clinic–patient and professional perceptions of inequity in rehabilitation of chronic pain. Scand J Caring Sci 2017; 31: 45–53.

- Ringqvist Å, Dragioti E, Björk M, Larsson B, Gerdle B. Moderate and stable pain reductions as a result of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation – a cohort study from the Swedish Quality Registry for Pain Rehabilitation (SQRP). J Clin Med 2019; 8: 905.

- McCracken LM, Eccleston C. A prospective study of acceptance of pain and patient functioning with chronic pain. Pain 2005; 118: 164–169.

- Nishi Y, Osumi M, Nobusako S, Takeda K, Morioka S. Avoidance behavioral difference in acquisition and extinction of pain-related fear. Front Behav Neurosci 2019; 13: 236.

- Wettstein M, Eich W, Bieber C, Tesarz J. Pain intensity, disability, and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: does age matter? Pain Medicine 2019; 20: 464–475.

- Persson E, Lexell J, Eklund M, Riviano-Fischer M. Positive effects of a musculoskeletal pain rehabilitation program regardless of pain duration or diagnosis. PM&R 2012; 4: 355–366.

- Di Rezze B, Nguyen T, Mulvale G, Barr NG, Longo CJ, Randall GE. A scoping review of evaluated interventions addressing developmental transitions for youth with mental health disorders. Child Care Health 2016; 42: 176–187.

- Merrick D, Sundelin G, Stalnacke BM. An observational study of two rehabilitation strategies for patients with chronic pain, focusing on sick leave at one-year follow-up. J Rehabil Med 2013; 45: 1049–1057.