REVIEW ARTICLE

FREQUENCY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS IN REHABILITATION SETTINGS: A SCOPING REVIEW

Elyse LADBROOK1, MNURSPRAC, Stephane BOUCHOUCHA2, PhD and Ana HUTCHINSON2, PhD

From the 1School of Nursing, Midwifery & Public Health, University of Canberra, Canberra and 2Centre for Quality and Patient Safety Research, School of Nursing & Midwifery, Deakin University, Burwood, Victoria, Australia

Objective: To synthesize the available evidence on medical complications occurring in adult patients in subacute inpatient rehabilitation, and to describe the impact on subacute length of stay and readmission to acute care.

Design: Scoping review.

Subjects: Adult patients, within the inpatient rehabilitation environment, who experienced medical complications, clinical deterioration and/or the requirement of transfer to acute care.

Methods: A systematic search of MEDLINE and CINAHL electronic databases was undertaken to identify primary research studies published in English and French during the period 2000-2021. Study reporting followed the standards indicated by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR).

Results: A total of 47 studies were identified for inclusion. Key results included differences in the type and frequency of complications according to admission type, the proportion of patients experiencing at least 1 complication, and complications associated with transfer to acute care.

Conclusion: Patients admitted for inpatient rehabilitation are at high risk of medical complications and may not be medically stable during their admission, requiring care by clinicians with expertise in functional rehabilitation, and ongoing management by members of the multidisciplinary team with expertise in acute general medicine, infectious diseases and recognition and response to clinical deterioration.

LAY ABSTRACT

Medical complications are associated with negative patient health outcomes and significant impact on healthcare utilization and delivery. A review was undertaken to scope available literature and explore medical complications as an important concept in relation to healthcare delivery and utilization for patients admitted to subacute care for inpatient rehabilitation. The results of the review highlighted that patients admitted for inpatient rehabilitation are at high risk of medical complications, with infections, neurological and cardiorespiratory complications being prominent. Patients admitted following stroke, traumatic brain injury/trauma or cancer are particularly vulnerable. The findings of this review emphasize the importance of including clinicians within the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team who have expertise in acute medicine and nursing, infection prevention and control, and recognition and response to clinical deterioration, to support the delivery of high-quality and safe care within inpatient subacute settings.

Key words: rehabilitation; healthcare utilization; healthcare delivery; infection; clinical deterioration.

Citation: J Rehabil Med 2022; 54: jrm00350. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v54.2752

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Oct 10, 2022; Epub ahead of print: Oct 26, 2022; Published: Dec 09, 2022

Correspondence address: Elyse Ladbrook, School of Nursing, Midwifery & Public Health, University of Canberra, 11 Kirinari Street Bruce, ACT 2617, Canberra, Australia. E-mail: elyse.ladbrook@canberra.edu.au

Inpatient rehabilitation is an integral component of healthcare delivery, providing opportunity for functional recovery and promotion of independence for patients during the post-acute care phase and ongoing support for complex medical conditions (1). Inpatient rehabilitation is typically provided in a geographically separate subacute care setting, and the availability of subacute care beds may improve patient flow through acute care and decrease acute care costs. Medical complications (complications), including adverse events and clinical deterioration, have the potential to interrupt rehabilitation programmes, lead to acute care readmission, and result in suboptimal outcomes, including increased costs to the patient and healthcare organizations (1).

The impact of complications and clinical deterioration on both patient outcomes and acute care costs is well documented (2, 3). Delivery of safe and high-quality healthcare, that promotes positive patient health outcomes, centres on the mitigation of risk, errors, and harm (4). Key policies and clinical practice guidelines are focused on core patient safety goals including decreasing risk for healthcare-associated complications, such as infections and falls, early recognition and prompt intervention for clinical deterioration, as well as effective interdisciplinary and consumer communication (3, 4).

Adverse patient health outcomes are associated with poor organizational leadership and failure to promptly recognize and respond to clinical deterioration (5). To improve patient outcomes, the organizational leadership team must exemplar clinical governance processes that support timely recognition of physiological variance and activation of rapid clinical review systems (5, 6). Rapid response teams and clinical escalation pathways are embedded into practice in acute care (7, 8); however, recent research suggests that in the subacute care setting recognition and response systems require development (9).

Subacute care services are an integral part of the healthcare system, supporting individuals to maintain their highest level of functional ability and quality of life at the interface between acute and community-based healthcare (10, 11). Although there has been extensive research evaluating the incidence and prevalence of healthcare-associated complications and clinical deterioration meeting escalation criteria in acute care, there is less research evaluating the impact of complications and clinical deterioration in sub-acute care.

The purpose of this scoping review is to synthesize the available evidence on frequency and type of complications occurring in the inpatient rehabilitation context, in different cohorts of patients (e.g. post-stroke, trauma, orthopaedic and cardiac rehabilitation) and to describe the impact of complications on patient health outcomes, healthcare utilization, the incidence of readmission to acute care and patient mortality.

METHODS

Design

A scoping review of the literature was performed, involving a systematic search of relevant electronic bibliographic databases and hand searching of reference lists. The methods used for this scoping review were informed by the methodology outlined by Peters et al. (12) to ensure a consistent approach to the conduct and reporting of the review (13). Study reporting followed the standards indicated by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) (13, 14). This review is registered with the OSF Registries (https://osf.io/9xyhk).

Research questions

The scoping review aimed to address the following questions:

- What proportion of patients, admitted to inpatient rehabilitation settings, experience at least 1 medical complication?

- What are the reported characteristics of medical complications experienced by patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation settings?

- What are the reported characteristics of medical complications that result in an interruption to rehabilitation and/or return to acute care?

Search strategy

Electronic searches were performed of MEDLINE Complete and CINAHL Complete via the EBSCO-host platform. Key search terms included: Medical Complications OR Complications, and Sub-acute Care, Rehabilitation OR Inpatient rehabilitation, AND Adverse Events OR acute care transfer OR, sub-acute care length of stay. Search terms were combined according to a PCC (Participant, Concept, Context) search strategy and included: adults requiring inpatient rehabilitation who experienced the occurrence of medical complications, clinical deterioration and/or the requirement of transfer to acute care (15, 16). An example of the search strategy used is outlined in Appendix S1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Study inclusion criteria were: primary research studies, undertaken in the inpatient rehabilitation or sub-acute environment, and published in English and French between 2000 and 2021. One team member is a native French speaker and this time-frame was used to support the identification of current literature, in French and English, in relation to trends in health service delivery and models of care. Studies conducted outside the inpatient rehabilitation/subacute environment were excluded.

Definitions

The following definitions were used in this study:

Medical complications (complications). A working definition was used to include physiological variation away from homeostasis, resulting from new onset or exacerbation of ongoing disease process (17) and/or occurrence of a hospital-acquired complication (for example falls, venous thromboembolism). Complications were broadly categorized into body systems and broader concepts, such as infection, pain, psychiatry, and adverse events.

Classification of hospital-acquired diagnoses. Classifications generated from medical record data that support hospitals to identify and monitor any adverse events, to improve the safety and quality of healthcare (18).

Clinical deterioration requiring escalation of care. Significant physiological variation leading to decompensation, associated with increased risk for adverse events including death, requiring prompt involvement of relevant clinical specialties and implementation of definitive care to address time-critical health needs (19, 20).

Hospital-associated complications. A list of adverse events used to monitor safety in addition to the Classification of Hospital Acquired Diagnoses (21).

Return to acute care. Inter-hospital transfer for the purposes of readmission to an acute care facility from an inpatient rehabilitation setting or subacute care facility (22).

Subacute phase. Care that occurs post-acute admission, where interventions are designed to support patients experiencing functional impairment and/or physical deconditioning to optimize functional recovery and quality of life. (23).

Inpatient rehabilitation setting. Healthcare setting where patients are admitted to a sub-acute care facility, either located within the acute hospital or in a stand-alone site, during the subacute phase of care where they are supported by nursing, medical and allied health professionals (1).

Study screening, quality appraisal and data analysis. Two researchers (EL and AFH) independently screened citations by title and abstract to exclude irrelevant articles and identify potential studies for full-text review. The same researchers reviewed the full text of articles retained following initial screening. Final decisions to include or exclude studies from the review were made independently, with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer (SB). Data from included studies was extracted into a spreadsheet: author; publication year; study purpose and design, outcomes measures and study findings. Two authors (EL and AFH) separately checked the data extraction of study findings.

Although not essential for scoping reviews, quality appraisals were conducted to provide an overview of the methodological rigour of included studies. Articles included in the review were appraised for methodological quality using the Joanna Briggs Institute Appraisal Checklists for cross-sectional, case-control or cohort studies, as appropriate (24). As the purpose of this review was to scope and synthesize extant peer-reviewed publications, studies were not excluded based on the quality review.

Data from the studies included the study location and design, type and frequency of complications reported, the proportion of patients that were reported to have experienced at least 1 medical complication, and the proportion who required return to acute care. Incomplete data or outcomes reported using different denominators were identified and described as required.

Data were summarized into studies that reported the prevalence of complications, the proportion of patients requiring return to acute care (RTAC) and the type and frequency of complications that resulted in RTAC. Data related to the type and frequency of complications and reasons for RTAC, are outlined in the appendices S3 and S4, respectively. This was undertaken to identify the most common type of medical complication reported, and to identify further research opportunities where additional systematic review and meta-analysis may be relevant.

RESULTS

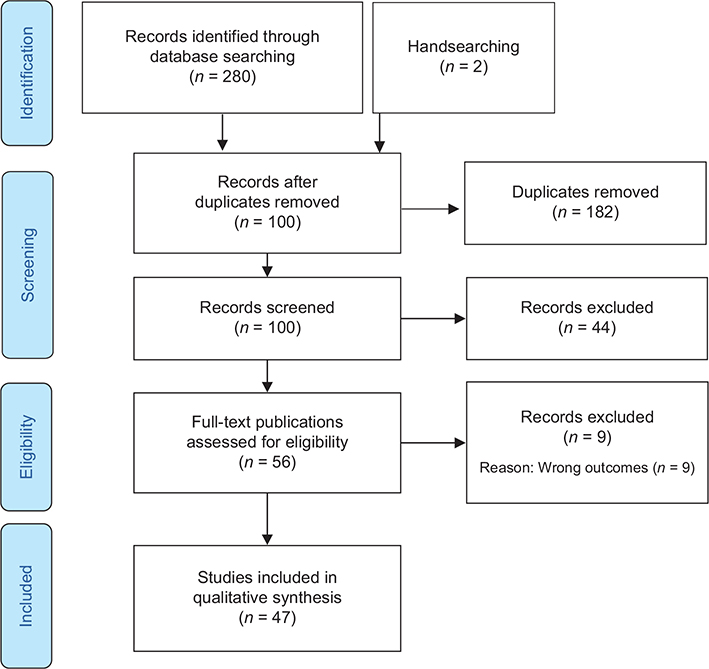

Database searching identified 280 records, with 2 additional studies found through hand-searching by title and abstract. A total of 56 papers were identified for full-text review, by 2 independent researchers (EL and AFH). Following full-text review against the study criteria 47 papers were included in this review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Description of included studies

A total of 47 studies were identified relating to complications (2, 17, 25–69). Studies were conducted across a variety of international healthcare settings, including North America (n = 22) (17, 27, 31, 33, 36–38, 40, 42, 44–46, 50, 51, 54, 59, 60, 62–66), Europe (n = 9) (26, 29, 34, 35, 43, 49, 52, 55, 69), Asia (n = 11) (28, 41, 47, 48, 53, 56–58, 61, 67, 68) and Oceania (n = 5) (2, 25, 30, 32, 39). Study cohorts included general rehabilitation (2, 25, 44, 47, 51, 56, 60, 65) and rehabilitation following: cerebrovascular accident (CVA) (17, 26, 28, 30, 35, 36, 38, 52, 57, 58, 61, 67, 68), acquired brain injury (32, 34, 43, 49, 54, 64, 66), spinal cord injury (37, 41, 48, 53, 55, 59, 62), post cardiac intervention (27, 39, 69), as well as musculoskeletal, cancer, and older persons with functional decline (29, 31, 33, 40, 42, 45, 46, 50, 63).

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was undertaken according to study design using recommended appraisal tools, the results are outlined in Appendix S2 (24). Overall, the included studies that used cross-sectional, case-control, quasi-experimental and randomized control trial designs met recommended quality appraisal criteria (2, 25, 33, 37). Only 1 study was noted to have not identified or described management of confounding variables (56). Quality appraisal of cohort studies showed recruitment of patients that were representative of the study population with exposure and outcomes measured using valid and reliable criteria (17, 26–32, 35, 36, 38–40, 68).

Frequency of complications

Thirty-two studies reported the type and/or frequency of complications occurring in subacute inpatient rehabilitation. Twenty-four studies (17, 26, 28, 29, 31, 34–36, 38–41, 47, 52, 53, 57, 58, 61–63, 66–69) reported the number of patients who experienced at least 1 medical complication during their episode of care, with the reported incidence varying from 3.4% (61) to 96.8% (63) (Table I). Six studies identified a proportion of patients who experienced 3 or more complications (28, 35, 36, 47, 58, 68), including Kuptniratsaikul et al. (58) who reported that 64.8% experienced at least 3 complications, and 53.5% experienced 4–5 complications during their rehabilitation admission (Table II).

| Study Author Country Study design | Patient population | Sample size N | At least 1 complication, n (%) | Overall length of stay (days) Mean (SD) | |||

| Abdul-Sattar (41) Saudi Arabia Prospective cohort |

Traumatic spinal cord injury | 90 | 63 (70.0) | 123 (45) | |||

| Aras et al. (43) Turkey Prospective cohort |

Traumatic brain injury | 40 | NA | 78.4 | |||

| Chen et al. (68) Taiwan Retrospective cohort |

Post stroke rehabilitation | 568 | 432 (76.1) | 25.29 (11.72) | |||

| Chu et al. (46) USA Retrospective cohort |

Bilateral Knee Arthroplasty | 94 | NA | 11.7 (4.2) | |||

| Civelek et al. (26) Turkey Retrospective cohort |

Post stroke rehabilitation | 81 | 72 (88.9) | Median 30.0 (IQR 19.3–54.3) | |||

| Doshi et al. (47) Singapore Retrospective cohort |

Inpatient rehabilitation | 140 | 76 (54.2) | - | |||

| Equebal et al. (48) India Retrospective cohort |

Spinal cord injury | 47 | NA | 93.34 (40.95) | |||

| Ganesh et al. (51) USA Prospective cross-sectional |

Acquired brain injury rehabilitation | 68 | NA | 64.1 (47.0) | |||

| Gökkaya et al. (52) Turkey Prospective cohort |

Post stroke rehabilitation | 83 | 75 (90.0) | 45.7 (23) | |||

| Gupta et al. (53) India Prospective cross-sectional |

Non traumatic spinal cord lesions | 64 | 58 (90.6) | 55.75 (40.91) | |||

| Hung et al. (28) Taiwan Cohort study |

Post stroke | 346 | 151 (43.6) | 28.0 (13.8) | |||

| Ikbali Afsar et al. (55) Turkey Retrospective cohort |

Spinal cord injury | 338 | NA | Neoplastic SCI 34.8 (41.03) |

Traumatic SCI 60.2 (53.1) |

p < 0.01 | |

| Janus-Laszuk et al. (35) Poland Retrospective cohort |

Post stroke | 1075 | 827 (76.9) | 35.7 (18.1) | |||

| Kennedy et al. (66) USA Retrospective cross-sectional |

Traumatic brain injury | 373 | 120 (32) | 19.8 (13.9) | |||

| Kim et al. (67) South Korea Before and after study Implementation of clinical pathway |

Post stroke | 497 | 53.8 (38.9) | ||||

| Before 196 | 181 (92.3) | ||||||

| After 301 | 262 (87.3) | p = 0.077 | |||||

| Kitisomprayoonkul et al. (57) Thailand Prospective cohort |

Post stroke | 118 | 83 (70.3) | No complications 23.04 (6.18) | Complications 60.66 (32.83) | p = 0.066 | |

| Kuptniratsaikul et al. (58) Thailand Prospective cohort |

Post stroke | 327 | 71.0 (n = 232) |

> 21 days (OR = 2.36; 95% CI = 1.26–4.43) |

|||

| Lew et al. (31) USA Retrospective chart audit |

General rehabilitation | 175 | 59 (33.7) | ||||

| Orthopaedic | n = 107 | 22 (20.5) | 7.3 (4.2) | ||||

| Traumatic brain injur1y | n = 42 | 26 (61.9) | 36.9 (23.4) | ||||

| Stroke | n = 26 | 11(42.3) | 22.4 (11.5) | ||||

| Mathews et al. (27) USA Retrospective cohort |

Cardiac patients with left ventricular assist devices and subsequent stroke | 21 | NA | Median 26 (IQR 13.5-34) | |||

| Marcassa et al. (69) Italy Prospective cohort |

Post cardiac surgery | 1200 | 274 (22.8) | 22 (+ / -12) | |||

| McKinley et al. (59) USA Prospective cohort |

Spinal cord injury | 117 | NA | Traumatic 42.97 (28.35) | |||

| Non-traumatic | n = 38 | Non-traumatic 26.36 (15.4) | |||||

| Traumatic | n = 79 | p < 0.05 | |||||

| McLean (36)a Canada Prospective cohort |

Stroke | 133 | 89 (67.0) | 39.5 (20.9) | |||

| Mulroy et al. (29) Ireland Retrospective analysis |

Functional decline | 155 | 106 (68.4) | Median 83 (IQR 2 – 460) | |||

| Pongratanakul et al. (61) Thailand Retrospective cohort |

Post stroke | 995 | 34 (3.4) | 26.7 (± 14.1) | |||

| Richard-Denis et al. (62) Canada Retrospective cohort |

Traumatic spinal cord injury | 150 | 68 (45.6) | 28.0 (± 14.1) |

|||

| Roth et al. (38) USA Retrospective chart audit |

Post stroke | 1845 | 1413 (76.6) | 28.0 (± 13.8) |

|||

| Roth et al. (17) USA Retrospective chart audit |

Post stroke | 1029 | 773 (75.1) | NA | |||

| Shiner et al. (39) Australia Retrospective cohort |

Post cardiac transplant | 116 | 39 (33.6) | 26.9 (± 21.2) |

|||

| Tennison et al. (63) USA Retrospective cohort |

Cancer rehabilitation | 165 | 158 (96.8) | NA | |||

| Whyte et al. (34) Denmark, Germany & USA Randomized control trial |

Non-penetrating traumatic brain injury | 184 | 152 (82.6) | NA | |||

| Yeung et al. (40) Canada Retrospective cohort |

Musculoskeletal | 275 | 119 (43.3) | 29.6 (± 16.4) |

|||

| Zhang et al. (64) USA Retrospective cohort |

Disorder of consciousness | 146 | 10.4 (SD 3.1) /patient | ||||

| aFull data only available for 112 patients within the sample, shown as 94.6% of the study sample experiencing medical complications. | |||||||

| NA: not available; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; SCI: spinal cord injury, OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. | |||||||

| Study | Population Sample size | Number of medical complications n (%) | At least 1 complication n (%) | |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 or more | |||

| Chen et al. (68) | Post-stroke rehabilitation N = 568 |

136 (23.9) | 163 (28.7) | 132 (23.2) | 137 (24.1) | 432 (76.1) |

| Doshi et al. (47) | Inpatient rehabilitation N = 140 |

54 (45.7) | 32 (22.9) | - | 25 (17.9) | 76 (54.2) |

| Hung et al. (28) | Post-stroke rehabilitation Inpatient rehabilitation ward N = 346 |

195 (56.4) | 110 (31.8) | 29 (8.4) | 12 (3.5) | 151 (43.6) |

| Janus-Laszuk et al. (35) | Post-stroke rehabilitation N = 1,075 |

248 (23.1) | 338 (31.4) | 276 (25.7) | 213 (19.8) | 827 (76.9) |

| Kitisomprayoonkul et al. (57) | Post-stroke rehabilitation N = 118 |

35 (29.7) | 34 (28.8) | 23 (19.4) | - | 83 (70.3) |

| Kuptniratsaikul et al. (58) | Post-stroke rehabilitation N = 327 |

95 (29.1) | 7 (2.1) | 13 (4.0) | 212 (64.8) | 232 (71.0) |

| Marcassa et al. (69) | Rehabilitation post cardiac surgery N = 5261 |

4,061 (11.0) | 604 (11.5) | 596 (11.3) | - | 1,200 (22.8) |

| McLean (36)a | Stroke rehabilitation unit N = 133 |

44 (33.0) | 43 (32.0) | 24 (18.0) | 9 (7.0) | 89 (67.0) |

| Yeung et al. (40) | General medical N = 269 |

185 (67.3) | 75 (27.3) | 9 (3.3) | - | 84 (31.2) |

| Orthopaedic N = 273 |

218 (81.0) | 46 (16.4) | 9 (3.3) | - | 55 (20.2) | |

| aIncomplete percentages reported. | ||||||

Twenty-four studies reported data on the frequency of complications in different patient cohorts (Table III) and 66.67% of these studies (n = 16) reported at least 1 complication in more than half of the study population. Studies reporting outcomes for patients receiving rehabilitation following cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) accounted for 54.17% (n = 13) (17, 26, 28, 31, 35, 36, 38, 52, 57, 58, 61, 67, 68) and 10 of these studies (76.92%) reported that more than 60% of patients with a CVA experienced a complication during their rehabilitation admission. Gökkaya et al. (52) reported that patients admitted following CVA experienced, a mean of, 7.1 (± 2.2) complications during their rehabilitation admission.

| Authors | Medical cohort Study setting | Population (N) | At least 1 complication n (%) |

| Spinal cord injury | |||

| Abdul-Sattar (41) | Saudi Arabia | 90 | 63 (70.0) |

| Gupta et al. (53) | India | 64 | 58 (90.6) |

| Richard-Denis et al. (62) | Canada | 150 | 68 (45.6) |

| Traumatic brain injury | |||

| Kennedy et al. (66) | USA | 373 | 120 (32.0) |

| Lew et al. (31) | USA | 42 | 26 (61.9) |

| Whyte et al. (34) | Denmark, Germany, USA | 184 | 152 (82.6) |

| Cerebral vascular accidents | |||

| Chen et al. (68) | Taiwan | 568 | 432 (76.1) |

| Civelek et al. (26) | Turkey | 81 | 72 (88.9) |

| Gökkaya et al. (52) | Turkey | 83 | 75 (90.0) |

| Hung et al. (28) | Taiwan | 346 | 151 (43.6) |

| Janus-Laszuk et al. (35) | Poland | 1,075 | 827 (76.9) |

| Kim et al. (67) | South Korea | 497 | 181 (92.3) |

| Kitisomprayoonkul et al. (57) | Thailand | 118 | 83 (70.3) |

| Kuptniratsaikul et al. (58) | Thailand | 327 | 232 (71.0) |

| Lew et al. (31) | USA | 26 | 11 (42.3) |

| McLean (36) | Canada | 133 | 89 (67.0) |

| Pongratanakul et al. (61) | Thailand | 995 | 34 (3.4) |

| Roth et al. (38) | USA | 1,845 | 1413 (76.6) |

| Roth et al. (17) | USA | 1,029 | 1413 (76.6) |

| General and aged care | |||

| Doshi et al. (47) | Singapore | 140 | 64 (45.7) |

| Mulroy et al. (29) | Ireland | 155 | 106 (68.4) |

| Musculoskeletal conditions | |||

| Lew et al. (31) | USA | 107 | 22 (20.5) |

| Yeung et al. (40) | Canada | 275 | 119 (43.3) |

| Cardiac | |||

| Marcassa et al. (69) | Italy | 5,261 | 1,200 (22.8) |

| Shiner et al. (39) | Cardiac transplant (Australia) |

116 | 39 (33.6) |

| Cancer | |||

| Tennison et al. (63) | USA | 165 | 158 (96.8) |

Whyte et al. (34) identified a substantial burden of complications in patients following non-penetrating brain injury (mean rate 2.85 complications per patient), with 70% experiencing moderate to severe complications. Lew et al. (31) reported the complication rate amongst patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), CVA and orthopaedic groups as 1.5, 1.2 and 1.0, respectively. Interestingly, Lew et al. (31) demonstrated that the presence of comorbidities increased complication risk in the TBI group (p < 0.05), but not in the orthopaedic or CVA cohorts. Both Janus-Laszuk et al. (35) and Kitisomprayoonkul et al. (57) found that, for patients with a CVA, the number of complications experienced impacted negatively on their functional recovery.

Marcassa et al. (69) found that the rate of complications was higher in patients with diabetes (p < 0.01), noting significant differences in the frequency of infectious complications (p < 0.01), renal dysfunction (p < 0.001), and heart failure (p < 0.05). The study conducted by Ikbali Afsar et al. (55) noted that urinary tract infections (UTI) and decubitus ulcers were more common in the traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) group compared with the neoplastic group (p < 0.05). Similarly, McKinley et al. (59) found that patients with TSCI were more likely to experience deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pressure injuries, pneumonia, orthostatic hypertension and spasticity (p < 0.05) than the non-traumatic spinal injury group.

Characteristics of medical complications

There was heterogeneity in the type and frequency of complications reported across the identified studies (Appendix S3) (17, 26–29, 31, 32, 34–36, 38, 39, 47, 48, 51–53, 55, 57–59, 61, 63, 68, 69). Hospital-acquired complications were noted to occur throughout most studies and included venous thromboembolism, pressure injuries, adverse drug events and falls. The most commonly reported complications were infections, and non-infectious neurological alterations. Infectious complications were identified in 26 studies, with UTIs, pneumonia and cellulitis reported as the most common (17, 26–28, 31, 34–36, 38, 41, 46–48, 51–53, 55, 57–59, 61, 64, 66–69). Six studies noted infection to have occurred in over half of the study population (26, 51, 53, 55, 59, 68). Neurological alterations were reported in 20 studies, with a variety of complications reported, including alterations in cognition, challenging behaviours, hydrocephalus, stroke progression, epilepsy, seizure and seizure-like activity (17, 26, 28, 29, 31, 34–36, 43, 46, 47, 51, 52, 57, 59, 61, 64, 67–69).

Risk factors for complications varied and included higher comorbidity scores, lower Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scores on admission or discharge, longer rehabilitation length of stay and/or greater neurological deficits (26, 28, 33, 68). Janus-Laszuk et al. (35) identified severe disability as associated with a 2.5-fold increase in the incidence of complications. Roth et al. (17) identified the following factors as increasing complication risk: greater neurological deficits, pressure ulcers, use of indwelling devices such as feeding tubes, indwelling urethral catheters, or tracheostomy tubes, abnormal serum electrolyte levels (p < 0.0001), hypoalbuminaemia (p < 0.001) and comorbidities, such as renal failure, anaemia or hypertension (p < 0.01). In addition to anxiety present on admission (adjusted odds ratio (adjusted OR) = 6.87; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 2.45 – 19.29), Kuptniratsaikul et al. (58) identified a timeframe of ≥ 1 month since the onset of stroke (adjusted OR = 2.12; 95% CI = 1.07 – 4.17) as an independent risk factor for complications. Hung et al. (28) showed a significant association between the occurrence of complications and female sex (p = 0.004), patients with greater neurological deficit (p < 0.0001), severe disability (p < 0.0001), use of an indwelling urinary catheter (p < 0.0001), and increased length of rehabilitation stay (p < 0.0001). Equebal et al. (48) found that there was no correlation between age and commonly reported complications; however, Chen et al. (68) highlighted an increase in the incidence of complications in patients aged > 65 years. Of note were complications occurring in patients aged > 75 years with a significant increase in the incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (p = 0.011), the presence of pressure ulcers (p < 0.001), hyponatremia (p = 0.029), and infections including symptomatic UTIs (p < 0.001) and scabies (p < 0.027) (68).

There was variation in the reported mean length of stay in subacute care across studies. The occurrence of complications was associated with an increased length of stay (LOS) in 10 studies, (26, 28, 31, 35, 40, 57–59, 62, 69). Yeung et al. (40) found that complications was a significant risk factor for an increased length of stay (p = 0.011). Marcassa et al. (69), Hung et al. (28) and Kitisomprayoonkul et al. (57) also reported a greater LOS amongst patients who experienced a complication compared with those that did not (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). Janus-Laszuk et al. (35) reported a mean increase in LOS per medical complication of approximately 5 days when a person experienced 2 or more complications during their rehabilitation admission. Kuptniratsaikul et al. (58) found that a LOS >21 days (adjusted OR = 2.34; 95% CI = 1.44–0.382) as well as the presence of anxiety on admission to rehabilitation (adjusted OR = 2.36; 95% CI = 1.26–4.43) were independent risk factors for the development of complications.

Characteristics of complications requiring acute care transfer

A total of 30 studies (2, 17, 25–30, 32–34, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44–47, 49, 50, 54, 56, 57, 60, 61, 63, 65, 69) measured the proportion of patients RTAC following subacute care admission as ranging from 2.89% (28) to 52.38% (27) (Table IV). Most studies reported patients RTAC only once, 4 studies identified patients requiring > 1 RTAC (25, 27, 32, 46), with McKechnie et al. (32) reporting that 18 patients (4.7%) had ≥ 3 acute care transfers. Patient cohorts commonly associated with higher rates of RTAC included: spinal cord injury, post cardiac transplant and frail, older adults whereas, stroke rehabilitation cohorts were associated with lower rates (26 – 30, 36, 37, 44). However, Alam et al. (42) found higher rates of RTAC in stroke (p = 0.001), brain (p = 0.004), and spinal cord injuries (p = 0.009). Other patient cohorts commonly reported as requiring RTAC included general rehabilitation (2, 25, 30, 47, 56, 65), orthopaedic (46), neoplasm (33, 42, 50), traumatic brain injury (44, 49, 54) and amputation (44, 45).

| Study author Country Study design | Population N | RTAC N (%) | Infection n (%) | Cardiac n (%) | Respiratory n (%) | Renal/urology n (%) | Neurological n (%) | Haematology n (%) | GI n (%) | Surgical n (%) | General medical n (%) | Other n (%) | Falls/fracture n (%) |

| General | |||||||||||||

| Alam et al. (42) USA Retrospective cohort |

293 | 293 (10.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Carney et al. (44) USA Retrospective cohort |

3,072 | 250 (8.1) | 55 (22.0) | 20 (8.0) | 35 (14.0) | – | 23 (9.0) | – | 18 (7.0) | 13 (5.0) | 23 (9.0) | 43 (17.0) | – |

| Considine et al. (2) Australia Cross-sectional |

136 | 136 (100)a | 17 (12.5) | 20 (14.7) | 14 (17.6) | 4 (3.0) | 22 (16.2) | – | 17 (12.5) | – | – | 17 (12.5) | 15 (11.0) |

| Considine et al. (25) Australia. Prospective case-time matched control study |

1,763 | 557b | 77 (12.8) | 82 (13.6) | 84 (13.9) | 22 (3.6) | 113 (18.7) | – | 81 (13.4) | 31 (5.1) | – | 30 (5.0) | 46 (7.6) |

| Doshi et al. (47) Singapore Retrospective cohort |

140 | 8 (5.7) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (37.5) | – | – | 1 (12.5) | – | 2 (25.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Faulk et al. (65) USA Retrospective cohort |

2,282 | 256 (11.22) | 57 (22.3) | 28 (10.9) | 68 (26.7) | – | 23 (8.9) | – | – | – | – | – | 27 (10.5) |

| Im et al. (56) Korea Retrospective chart audit |

1,301 | 121 (9.3) | 31 (25.6) | 26 (21.5) | – | 53 (4.1) | 22 (18.2) | 4 (3.3) | 4 (3.3) | 18 (14.9) | – | 11 (9.1) | – |

| Pinto et al. (60) USA Retrospective cohort |

2,312 | 228 (9.9) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 (4.4) | 30 (13.2) | – | – | 188 (82.4) |

| Orthopaedic | |||||||||||||

| Cheng et al. (45) USA Cross-sectional |

118 | 19 (16.1) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (15.8) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (5.3) | – | 1 (5.3) | 2 (10.6) | – | – | – |

| Chu et al. (46) USA Cross-sectional |

94 | 8 (8.5) | 20 (21.3) | 5 (5.3) | – | – | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.3) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | – |

| Post cerebrovascular accident | |||||||||||||

| Civelek et al. (26) Turkey Retrospective cohort Study |

81 | 9 (11.1) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.7) | – | – | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | – | – | – | – |

| Hung et al. (28) Taiwan Retrospective cohort |

346 | 10 (2.89) | 3 (30.0) | – | – | – | 5 (50.0) | – | – | 1 (10.0) | – | 1 (10.0) | – |

| Katrak et al. (30) Australia Retrospective cohort |

29 | 80 (11.0) | 13 (16.23) | 8 (10.0) | – | – | 7 (8.8) | 7 (8.8) | 2 (2.5) | 12 (15.0) | – | 26 (32.5) | 5 (6.3) |

| Kitisomprayoonkul et al. (57) Thailand Prospective cohort |

118 | 14 (11.8) | 5 (35.7) | 3 (21.4) | – | – | 4 (3.4) | 1 (7.1) | – | – | 1 (7.1) | – | – |

| McLean (36) Canada Prospective cohort |

133 | 2 (1.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (0.75) | – | – | – | 1 (0.75) |

| Pongratanakul et al. (61) Thailand Retrospective chart audit |

995 | 32 (3.2) | 15 (46.9) | 3 (9.4) | – | – | 10 (31.2) | – | – | – | – | 4 (12.5) | – |

| Roth et al. (17) USA Retrospective chart audit |

1,029 | 197 (19.0) | 30 (15.2) | 52 (26.4) | – | 4 (2.0) | 30 (15.2) | 48 (24.4) | 18 (9.1) | – | – | 4 (2.0) | 5 (2.5) |

| Acquired brain injury | |||||||||||||

| Formisano et al. (49) Italy Retrospective cohort |

1470 | 451 (30.7) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hammond et al. (54) USA Prospective cohort |

2130 | 183 (8.6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 110 (52.0) | 94 (45.0) | 5 (3.0) | – |

| McKechnie et al. (32) Australia Retrospective cohort |

383 | 83 (22.0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Whyte et al. (34) Denmark, Germany & USA Randomized control trial |

184 | 29 (15.8) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Marcassa et al. (69) Italy Prospective cohort |

5261 | 212 (4.0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mathews et al. (27) USA Retrospective cohort |

21 | 11 (52.4) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) | – | – | 4 (36.4) | – | 7 (63.6) | – | – | – | – |

| Shiner et al. (39) Australia Retrospective cohort |

116 | 39 (33.6) | 13 (33.3) | 3 (7.7) | 14 (35.9) | 3 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.6) | – | – | 3 (7.7) | – |

| Other | |||||||||||||

| Fu et al. (33) USA Cross-sectional |

122 | 32 (26.0) | 11 (34.4) | 6 (18.75) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (6.3) | 7 (21.9) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | – | 1 (3.1) | – |

| Fu et al. (50) USA Retrospective cohort |

30 | 9 (30.0) | 2 (22.2) | – | – | – | 1 (16.7) | – | – | – | 3 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | – |

| Mulroy et al. (29) Ireland Retrospective cohort |

155 | 20 (17.8) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Robinson et al. (37) USA Retrospective case-control |

137 | 37 (19.8) | 10 (27.0) | 3 (8.0) | 6 (16.0) | – | 10 (27.0) | – | 1 (3.0) | 6 (16.0) | – | 1 (3.0) | – |

| Tennison et al. (63) USA Retrospective cohort |

165 | 31 (18.8) | 9 (29.0) | 2 (6.5) | 5 (16.1) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (12.9) | – | – | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.7) | – |

| Yeung et al. (40) Canada Retrospective |

275 | 8 (2.9) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| aInclusion criterion required need for acute care transfer. | |||||||||||||

| bCase refers to number of patients requiring acute care transfer, control refers to patients not requiring acute care transfer. | |||||||||||||

| RTAC: return to acute care; GI: gastrointestinal. | |||||||||||||

Complications noted as contributing factors for unplanned RTAC included infection, respiratory failure/distress, cardiac complications, changes to neurological function, seizure activity, renal failure, venous thromboembolism, fractures, dislocations, and adverse events, such as falls (2, 17, 27, 32, 33, 37, 39, 40, 45). A detailed breakdown of each category of contributing factors is provided in Appendix S4. Infectious complications were noted as the most common cause of RTAC in 12 studies (26, 30, 33, 37, 39, 44–46, 56, 57, 61, 63). Hammond et al. (54) noted infection as the most common reason for RTAC in medical patients. Whyte et al. (34) identified pneumonia as the most common reason for RTAC, and Carney et al. (44) showed infections (including pneumonia) and other pulmonary complications as the most common causes for RTAC. Alam et al. (42) identified that infection was the most common reason for RTAC (p = 0.001) within the neoplasm cohort and cardiopulmonary factors the most common reason in patients without neoplasm (p < 0.001).

There was variation in findings regarding risk factors associated with the need for RTAC. Pongratanakul et al. (61) noted that age (adjusted OR 1.08; 95% CI 1.04–1.13; p < 0.001), the presence of a feeding tube (adjusted OR 3.94; 95% CI 1.30–11.96; p = 0.015) and anaemia (adjusted OR 2.62; 95% CI 1.04–6.57; p = 0.04) were independently associated with interruption to stroke rehabilitation programmes. Whereas, Mathews et al. (27) found that age was not a significant risk factor for RTAC. Faulk et al. (65) noted time of admission and total Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score were significant predictors for RTAC, (p = 0.0017 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Similarly, McKechnie et al. (32) found that motor FIM score (p < 0.001) and Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) (p = 0.001) were independent risk factors for RTAC. In their prediction model Cheng et al. (45) found male sex was the only significant risk factor (p = 0.01). Tennison et al. (63) found both tachycardia and the need for frequent blood transfusions were independent risk factors for RTAC. Considine et al. (25) highlighted several factors that increased the risk of emergency inter-hospital transfer including: serious adverse events during the index acute care admission, increased vital sign monitoring in the 24 h prior to transfer, male sex, being born in a non-English speaking country, and a lower FIM score on admission to subacute care (25). Other risk factors identified across studies included: elevated white blood cell count, abnormal haemoglobin level on admission, indwelling devices, such as an indwelling urethral catheter or feeding tube, greater neurological deficit, or a history of pneumonia (p < 0.001), cardiac arrhythmia (p < 0.01) and dyspnoea requiring oxygen (17, 27).

Timing of transfers varied; Robinson et al. (37) noted that 73% of RTAC occurred within 10 days of subacute care admission, Carney et al. (44) found 22% (n = 55) were transferred within 3 days of admission, Faulk et al. (65) reported 22.3% (n = 57) returned within 72 h of subacute admission, and Fu et al. (2019) found a median of 10 days until RTAC. Considine et al. (25) found the median subacute length of stay prior to RTAC, was 11 days, with only 8.9% of all transfers occurring within the first day of subacute care admission. Amongst patients who required RTAC the subacute care LOS ranged between 11.7 days (SD ± 6.4 days) (54) and 29.6 days (SD ± 16.4 days) (40). Four studies, Hammond et al. (54), Im et al. (56), Mathews et al. (27) and McKechnie et al. (32), reported a significant increase in overall LOS associated with patients requiring RTAC (p ≤ 0.001, < 0.001,0.003, and < 0.001, respectively). In contrast, Civelek et al. (26) and Robinson et al. (37) found no difference in LOS, while Faulk et al. (65) found the LOS of patients requiring RTAC was shorter.

Eight articles (2, 17, 25, 36, 39, 44, 50, 61) reported death as an outcome in relation to complications or when patients required RTAC. Pongratanakul et al. (61) noted that all deaths were amongst patients who had experienced complications during their subacute care admission. Studies by McLean (36) and Roth et al. (17), noted 3 deaths during the study period, with McLean (36) highlighting that 2 deaths were related to infectious complications. Shiner et al. (39) noted that all recorded deaths (n = 5) were related to underlying disease states and were amongst patients who had required RTAC, and subsequently died in acute care (39). Carney et al. (44) reported an increased proportion of deaths in patients who required RTAC within the first 3 days of admission for rehabilitation (11%) in comparison with those who were transferred later (5%). In a single site study Considine et al. (2) reported an increase in the proportion of patients who died after transfer to acute care, noting an inpatient mortality rate of 14.7% (n = 15). In their multi-site study Considine et al. (25) noted that 1.3% of patients (n = 8) died in emergency following RTAC, and 10.2% (n = 50) died during their subsequent acute care readmission. Fu et al. (50) noted that patients who required RTAC had a median survival of 4.1 months in comparison with patients who were discharged home or to a skilled nursing facility (median survival 9.4 months, p = 0.107).

DISCUSSION

The findings in this scoping review highlight the variation and frequency of complications occurring amongst patients admitted for inpatient rehabilitation, with patients admitted following CVA, TBI or cancer diagnosis being particularly vulnerable. Infectious complications were prominent across the included studies, highlighting the need for improved infection prevention and control practices in the subacute inpatient rehabilitation setting. The high reported frequency of neurological complications and patients requiring acute care readmission emphasizes the importance of developing sub-acute care clinicians’ skills in recognition and response to clinical deterioration.

Despite considerable concordance in the reported prevalence estimates across different patient cohorts, there was considerable methodological heterogeneity across the identified studies that would make conducting a formal systematic review and meta-analysis inappropriate. In addition, there was limited critical evaluation of individual patient risk factors for complications and the impact of complications on patient outcomes. Where individual risk factors were explored there was limited analysis to identify and adjust for possible confounding variables, with the majority of studies only presenting descriptive rather than analytical data. Further rigorous multi-site research using large sample sizes is required to evaluate the impact of pre-existing conditions, reasons for rehabilitation admission and other patient risk factors on the incidence, type, and severity of complications. In addition, in-depth organizational case studies are needed to support a greater understanding of the contextual factors that contribute to the incidence of complications occurring within individual health services.

Whilst the identified studies describe complications occurring within inpatient rehabilitation settings, the literature does not address strategies to decrease the incidence, severity and need for RTAC for ongoing management. The occurrence of complications was both a predictor and consequence of a prolonged length of stay in the rehabilitation setting (28, 57, 58). Although some complications may be considered minor, studies evaluating the frequency of acute care readmission following clinical deterioration highlights that these episodes contribute to adverse patient outcomes, including increased risk of death (2, 17, 25, 36, 39, 44, 50, 61). Understanding both contributing factors and key characteristics of complications that cannot be managed within the subacute setting, could support a deeper understanding of the impact of complications on patient outcomes, health service utilization and delivery. This supports the argument by Hammond et al. (54) that RTAC is influenced by patient characteristics as well as contextual factors related to the specific site, resources, and staff skill mix.

Infections, such as UTI and pneumonia, as well as cardiorespiratory and neurological complications, were prominent events that resulted in acute clinical deterioration and the need for RTAC across all patient cohorts (2, 25, 26, 33, 37, 39, 42, 44–47, 56, 57, 61, 63, 65). This is an important finding, as it highlights focused areas for practice improvement. In the area of infection prevention and control specifically, there is a need for strategies to prevent worsening of minor infections present at the time of admission and to decrease the incidence of new-onset infections (51). A consistent association was found between the use of indwelling devices, such as urinary catheters, and an increased frequency of infectious complications (26, 57). This finding demonstrates the importance of developing targeted quality improvement initiatives to promote best practice in the management of indwelling devices and care pathways with explicit goals to optimize duration of use. However, further research is required to understand individual risk factors for different type of infections within patient cohorts.

Neurological complications were also prominent complications identified by studies reporting both type and frequency of complications, and patients requiring RTAC (17, 25–31, 33–37, 39, 42–44, 46, 47, 50–52, 57, 59, 61, 63–65, 67–69). Across the included studies there was considerable heterogeneity in reason for subacute care admission, cohorts included patients admitted for rehabilitation following neurological, orthopaedic, or cardiac events, and those admitted for general rehabilitation. This is an important finding that highlights the diverse nature of complications that exist within inpatient rehabilitation cohorts. Demonstrating the need for safe, evidence-based and quality healthcare that is tailored to individual patient needs, to minimize adverse patient outcomes and financial costs associated with increased length of stay, morbidity, and mortality (31, 43, 51).

In addition, the high frequency of cardiorespiratory complications, electrolyte or haematological abnormalities further confirms the argument posed by Hung et al. (28), that admission for inpatient rehabilitation does not equate to medical stability. The need for models of care in inpatient rehabilitation settings that include timely access to medical review of unstable patients is also demonstrated by these findings (70).

The results of this review highlight the complex health issues experienced by patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation and challenge the notion that patients admitted to inpatient subacute rehabilitation do not require expert medical management. This also calls into question assumptions about the level of nursing skill and supervision required in inpatient rehabilitation settings, which typically employ a lower nurse to patient ratio and a higher proportion of less experienced or qualified nursing staff (71–73). Based on the available data it was not possible to differentiate whether reported complications occurred: (i) due to deterioration of a pre-existing condition, (ii) associated with the primary reason for subacute care admission, (iii) as a result of hospital-acquired complication, or (iv) as a new-onset condition. Prospective interventional studies are needed to evaluate whether changes in the model of care and introduction of clinical pathways that include proactive monitoring, identification and response to clinical deterioration, decrease the incidence and adverse sequelae of these events.

Study limitations

One limitation of this review is that most included studies were observational and relied on retrospective analysis of administrative datasets. It was therefore not possible to evaluate or control for all the causative factors driving the high rates of complications reported. Moreover, the heterogeneity in study design and definitions used across studies does not support the use of meta-regression statistical techniques to evaluate the impact of patient factors on the occurrence of complications.

CONCLUSION

Patients admitted for inpatient rehabilitation are at high risk of medical complications during their admission to sub-acute care. The review findings highlight the complexity and heterogeneity of patients admitted for inpatient rehabilitation and their increased risk for cardiorespiratory, neurological, and infection-related complications. In addition to care by clinicians with expertise in functional rehabilitation, these patients require ongoing management by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in acute general medicine, infection prevention and control, and recognition and response to clinical deterioration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Detailed data collection tables are included in Appendices S1–S4.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Agency for Clinical Innovation. ACI Rehabilitation Network Report: principles to support rehabilitation care. 2015 [updated 2019 April 29; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/500900/rehabilitation-principles.pdf

- Considine J, Mohr M, Lourenco R, Cooke R, Aitken M. Characteristics and outcomes of patients requiring unplanned transfer from subacute to acute care. Int J Nurs Pract 2013; 19: 186-196. DOI: 10.1111/ijn.12056

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards second edition. 2021 [updated 2021 May; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-05/national_safety_and_quality_health_service_nsqhs_standards_second_edition_-_updated_may_2021.pdf

- Joint Comission International. International patient safety goals. 2017. [updated 2017 June; cited 2022 March 13] Available from: https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/-/media/jci/jci-documents/offerings/other-resources/jci_2017_ipsg_infographic_062017.pdf

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Consensus Statement: Essential elements for recognising and responding to acute physiological deterioration. 2017 [updated 2017 January; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Consensus-Statement-clinical-deterioration_2017.pdf

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Model Clinical Governance Framework. 2017 [updated 2017 November; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Model-Clinical-Governance-Framework.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acutely ill adults in hospital: recognising and responding to deterioration. 2021 [updated 2017 July 25; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG50

- Australian Commission on Safety and Qualty in Health Care. Recognising and responding to acute deterioration standard. [date unknown; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/recognising-and-responding-acute-deterioration-standard

- Considine J, Street M, Botti M, O’Connell B, Kent B, Dunning T. Multisite analysis of the timing and outcomes of unplanned transfers from subacute to acute care. Aust Health Rev 2015; 39: 387–394. DOI: 10.1071/AH14106

- Davis J, Morgans A, Stewart J. Developing an Australian health and aged care research agenda: a systematic review of evidence at the subacute interface. Aust Health Rev 2016; 40: 420–427. DOI: 10.1071/AH15005

- Considine J, Street M, Hutchinson AM, Mohebbi M, Rawson H, Dunning T, et al. Vital sign abnormalities as predictors of clinical deterioration in subacute care patients: a prospective case-time-control study. Int J Stud Nurs 2020; 108:103612. DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103612

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Baldini Soares C. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13: 141–146. DOI:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 Version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: JBI; 2020. [updated 2020; cited 2022 March 13] Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467–473. DOI: 10.7326/M18-0850.

- McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Ryan RE, Thomson H, J, Johnston R, V, Thomas J. Chapter 3: Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. In: Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 612020. [updated 2022 February; cited 2022 March 13] Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-03

- da Costa Santos CM, de Mattos Pimenta CA, Nobre MRC. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2007; 15: 508–511. DOI: 10.1590/s0104-11692007000300023.

- Roth EJ, Lovell L, Harvey RL, Heinemann AW, Semik P, Diaz S. Incidence of and risk factors for medical complications during stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2001; 32: 523–529. DOI: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.523.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Classification of Hospital Acquired Diagnoses. [date unknown; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/indicators/classification-of-hospital-acquired-diagnoses

- Jones D, Mitchell I, Hillman K, Story D. Defining clinical deterioration. Resuscitation 2013; 84:1029–1034. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.013

- Padilla RM, Mayo Ann M. Clinical deterioration: A concept analysis. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: 1360–1368. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.14238. Epub 2018 Feb 15.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Hospital-acquired complications (HACs). [date unknown; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/indicators/hospital-acquired-complications

- Considine J, Fox K, Plunkett D, Mecner M, O’Reilly M, Darzins P. Factors associated with unplanned readmissions in a major Australian health service. Aust Health Rev 2019; 43: 1–9. DOI: 10.1071/AH16287

- World Health Organization. World report on disability. 2011 [updated 2011 December 14 cited 2011 December 14]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools. [date unknown; cited 2022 March 13]. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- Considine J, Street M, Bucknall T, Rawson H, Hutchison AF, Dunning T, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of emergency interhospital transfers from subacute to acute care for clinical deterioration. Int J Qual Health Care 2019; 31: 117–124. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzy135

- Civelek GM, Atalay A, Turhan N. Medical complications experienced by first-time ischemic stroke patients during inpatient, tertiary level stroke rehabilitation. J Phys Ther Sci 2016; 28: 382–391. DOI: 10.1589/jpts.28.382

- Mathews A, Goodman DA, Rydberg L. Outcomes of acute inpatient rehabilitation of patients with left ventricular assist devices and subsequent stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2019; 98: 800–805. DOI: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001200.

- Hung JW, Tsay TH, Chang HW, Leong CP, Lau YC. Incidence and risk factors of medical complications during inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Chang Gung Med J 2005; 28: 31–38. Available from: http://cgmj.cgu.edu.tw/2801/280105.pdf

- Mulroy M, O’Keeffe L, Byrne D, Coakley D, Casey M, Walsh B, et al. Medical complications and outcomes at an onsite rehabilitation unit for older people. Ir J Med Sci 2013; 182: 499–502. DOI: 10.1007/s11845-013-0922-1

- Katrak PH, Black D, Peeva V. Stroke rehabilitation in Australia in a freestanding inpatient rehabilitation unit compared with a unit located in an acute care hospital. PM R 2011; 3: 716–722. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.04.011.

- Lew H, Lee E, Date E, Zeiner H. Influence of medical comorbidities and complications on FIM™ change and length of stay during inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 81: 830–837. DOI: 10.1097/00002060-200211000-00005

- McKechnie D, Fisher MJ, Pryor J, McKechnie R. Predictors of unplanned readmission to acute care from inpatient brain injury rehabilitation. J Clin Nurs 2020; 29: 593–601. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.15118

- Fu JB, Lee J, Shin BC, Silver JK, Smith DW, Shah JJ, et al. Return to the primary acute care service among patients with multiple myeloma on an acute inpatient rehabilitation unit. PM R 2017; 9: 571–578. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.12.007

- Whyte J, Nordenbo AM, Kalmar K, Merges B, Bagiella E, Chang H, et al. Medical complications during inpatient rehabilitation among patients with traumatic disorders of consciousness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94: 1877–1883. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.12.027

- Janus-Laszuk B, Mirowska-Guzel D, Sarzynska-Dlugosz I, Czlonkowska A. Effect of medical complications on the after-stroke rehabilitation outcome. NeuroRehabilitation 2017; 40: 223–232. DOI: 10.3233/NRE-161407

- McLean DE. Medical complications experienced by a cohort of stroke survivors during inpatient, tertiary-level stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 466–439. DOI: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00484-2

- Robinson DM, Bazzi MS, Millis SR, Bitar AA. Predictors of readmission to acute care during inpatient rehabilitation for non-traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2018; 41: 444–449. DOI: 10.1080/10790268.2018.1426235

- Roth EJ, Lovell L. Seven-year trends in stroke rehabilitation: Patient characteristics, medical complications, and functional outcomes. Top Stroke Rehabil 2003; 9: 1–9. DOI: 10.1310/PLFL-UBHJ-JNR5-E0FC

- Shiner CT, Woodbridge G, Skalicky DA, Faux SG. Multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation following heart and/or lung transplantation-examining cohort characteristics and clinical outcomes. PM R 2019;11: 849–857. DOI 10.1002/pmrj.12057

- Yeung S-MT, Davis AM, Soric R. Factors influencing inpatient rehabilitation length of stay following revision hip replacements: a retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 252. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-252

- Abdul-Sattar AB. Predictors of functional outcome in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury after inpatient rehabilitation: In Saudi Arabia. NeuroRehabilitation 2014; 35: 341–347. DOI: 10.3233/NRE-141111.

- Alam E, Wilson RD, Vargo MM. Inpatient cancer rehabilitation: a retrospective comparison of transfer back to acute care between patients with neoplasm and other rehabilitation patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 89: 1284–1289. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.014

- Aras MD, Kaya A, Cakc A, Gökkaya KO. Functional outcome following traumatic brain injury: the Turkish experience. Int J Rehabil Res 2004; 27: 257–260. DOI: 10.1097/00004356-200412000-00001

- Carney ML, Ullrich P, Esselman P. Early unplanned transfers from inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2006; 85: 453–460; quiz 61–3. DOI: 10.1097/01.phm.0000214279.04759.45

- Cheng R, Smith S, Kalpakjian CZ. Comorbidity has no impact on unplanned discharge or functional gains in persons with dysvascular amputation. J Rehabil Med 2019; 51: 369–375. DOI: 10.2340/16501977-2554

- Chu SK, Babu AN, McCormick Z, Mathews A, Toledo S, Oswald M. Outcomes of inpatient rehabilitation in patients with simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty. PMR 2016; 8:761–766. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.11.005

- Doshi VS, Say JH, Young SH, Doraisamy P. Complications in stroke patients: a study carried out at the Rehabilitation Medicine Service, Changi General Hospital. Singapore Med J 2003; 44: 643–652. Available from: https://www.sma.org.sg/smj/4412/4412a5.pdf

- Equebal A, Anwer S, Kumar R. The prevalence and impact of age and gender on rehabilitation outcomes in spinal cord injury in India: a retrospective pilot study. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 409–412. DOI: 10.1038/sc.2013.5

- Formisano R, Azicnuda E, Sefid MK, Zampolini M, Scarponi F, Avesani R. Early rehabilitation: benefits in patients with severe acquired brain injury. Neurol Sci 2016; 37: 181–184. DOI: 10.1007/s10072-016-2724-5

- Fu JB, Molinares DM, Morishita S, Silver JK, Dibaj SS, Guo Y, et al. Retrospective analysis of acute rehabilitation outcomes of cancer inpatients with leptomeningeal disease. PMR 2020; 12: 263–270. DOI: 10.1002/pmrj.12207

- Ganesh S, Guernon A, Chalcraft L, Harton B, Smith B, Louise-Bender Pape T. Medical comorbidities in disorders of consciousness patients and their association with functional outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94:1899–1907. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.12.026.

- Gökkaya N, Aras M, Cardenas D, Kaya A. Stroke rehabilitation outcome: the Turkish experience. Int J Rehabil Res 2006; 29: 105–111. DOI: 10.1097/01.mrr.0000191852.03317.2b

- Gupta A, Taly AB, Srivastava A, Murali T. Non-traumatic spinal cord lesions: epidemiology, complications, neurological and functional outcome of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 307–311. DOI: 10.1038/sc.2008.123

- Hammond FM, Horn SD, Smout RJ, Beaulieu CL, Barrett RS, Ryser DK, et al. Readmission to an acute care hospital during inpatient rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 96: s329–s303.e1. DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.026

- Ikbali Afsar S, Cosar SNS, Yemişçi OU, Bölük H. Inpatient rehabilitation outcomes in neoplastic spinal cord compression vs. traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2020; 45: 221–229. DOI: 10.1080/10790268.2020.1794713.

- Im S, Lim DY, Sohn MK, Kim Y. Frequency of and reasons for unplanned transfers from the inpatient rehabilitation facility in a tertiary hospital. Ann Rehabil Med 2020; 44: 151–157. DOI: 10.5535/arm.2020.44.2.151

- Kitisomprayoonkul W, Sungkapo P, Taveemanoon S, Chaiwanichsiri D. Medical complications during inpatient stroke rehabilitation in Thailand: a prospective study. J Med Assoc Thai 2010; 93: 594–600.

- Kuptniratsaikul V, Kovindha A, Suethanapornkul S, Manimmanakorn N, Archongka Y. Complications during the rehabilitation period in Thai patients with stroke: a multicenter prospective study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 88: 92–99. DOI: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181909d5f.

- McKinley WO, Tewksbury MA, Godbout CJ. Comparison of medical complications following nontraumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2002; 25: 88–93. DOI: 10.1080/10790268.2002.11753607

- Pinto SM, Galang G. Venous thromboembolism as predictor of acute care hospital – transfer and inpatient rehabilitation length of stay. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2017; 96: 367–373. DOI: 10.1080/10790268.2002.11753607.

- Pongratanakul R, Thitisakulchai P, Kuptniratsaikul V. Factors related to interrupted inpatient stroke rehabilitation due to acute care transfer or death. NeuroRehabilitation 2020; 47: 171–179. DOI: 10.3233/NRE-203187

- Richard-Denis A, Nguyen B-H, Mac-Thiong J-M. The impact of early spasticity on the intensive functional rehabilitation phase and community reintegration following traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2020; 43: 435–443. DOI: 10.1080/10790268.2018.1535638

- Tennison JM, Fricke BC, Fu JB, Patel TA, Chen M, Bruera E. Medical complications and prognostic factors for medically unstable conditions during acute inpatient cancer rehabilitation. JCO Oncol Pract 2021; 17: e1502–e1511. DOI: 10.1200/OP.20.00919

- Zhang B, Huang K, Karri J, O’Brien K, DiTommaso C, Li S. Many faces of the hidden souls: medical and neurological complications and comorbidities in disorders of consciousness. Brain Sci 2021; 11: 608. DOI:10.3390/brainsci11050608

- Faulk CE, Cooper NR, Staneata JA, Bunch MP, Galang E, Fang X, et al. Rate of return to acute care hospital based on day and time of rehabilitation admission. PM R 2013; 5: 757–762. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.06.002

- Kennedy RE, Livingston L, Marwitz JH, Gueck S, Kreutzer JS, Sander AM. Complicated mild traumatic brain injury on the inpatient rehabilitation unit: a multicenter analysis. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2006; 21: 260–271. DOI: 10.1097/00001199-200605000-00006.

- Kim JH, Byun HY, Son S, Lee JH, Yoon CH, Lee ES, et al. Retrospective assessment of the implementation of critical pathway in stroke patients in a single university hospital. Ann Rehabil Med 2014; 38: 603–611. DOI: 10.5535/arm.2014.38.5.603

- Chen CM, Hsu HC, Chang CH, Lin CH, Chen KH, Hsieh WC, et al. Age-based prediction of incidence of complications during inpatient stroke rehabilitation: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2014; 14: 41. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-41

- Marcassa C, A G, Corrá A, Giannuzzi P. Greater functional improvement in patients with diabetes after rehabilitation following cardiac surgery. Diabet Med 2015; 33: 1067–1075. DOI: 10.1111/dme.12882

- Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. Standards for the provision of inpatient adult rehabilitation medicine services in public and private hospitals. 2019 [cited 2019 Feburary]. Available from: https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/advocacy-library/afrm-standards-for-the-provision-of-inpatient-adult-rehabilitation-medicine-services-in-public-and-private-hospitals.pdf?sfvrsn=4690171a_4.

- Nelson A, Powell-Cope G, Palacios P, Luther SL, Black T, Hillman T, et al. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes in inpatient rehabilitation settings. Rehabil Nurs 2007; 32: 179–202. DOI: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00173.x.

- Pryor J, Walker A, O’Connell B, Worrall-Carter L. Opting in and opting out: a grounded theory of nursing’s contribution to inpatient rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil 2009; 23: 1124–1135. DOI: 10.1177/0269215509343233

- Abusalem S, Polivka B, Coty MB, Crawford TN, Furman CD, Alaradi M. The relationship between culture of safety and rate of adverse events in long-term care facilities. J Patient Saf 2021; 17: 299–304. DOI: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000587