REVIEW ARTICLE

ASSESSMENT BY PROXY OF THE SF-36 AND WHO-DAS 2.0. A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Juan David HERNÁNDEZ, MD, María Alejandra SPIR, MD, Kelly PAYARES, MD, Ana María POSADA, MD, Msc Clinical Epidemiology, Fabio Alonso SALINAS, MD, Héctor Iván GARCÍA, MD, MSc Public Health, MSc Epidemiology, Luz H. LUGO-AGUDELO, MD, MSc Epidemiology

Health Rehabilitation Group, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Background and objective: In some cases, for the evaluation of the health status of patients it is not possible to obtain data directly from the patient. The objective of this study was to determine if the instruments that cannot be applied to the patient can be completed by a proxy.

Methods: A systematic review of the literature was carried out and 20 studies were included. The instruments reviewed in this synthesis were: Short Form-36 (SF-36), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), WHODAS 2.0, Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Disability Rating Scale (DRS).

Results: The levels of agreement between the responses of the patients and the proxies were good, mainly when evaluating HRQoL and functioning with the SF-36 and WHODAS 2.0 instruments, respectively, with a higher level of agreement in the more objective and observable domains such as physical functioning and lower level of agreement in less objective domains, such as emotional or affective status, and self-perception.

Conclusion: In patients who cannot complete the different instruments, the use of a proxy can help avoid the omission of responses.

LAY ABSTRACT

People with certain mental or neurological illnesses are often unable to answer questions about their health status, functional ability, or quality of life. In some cases, a relative or a person who knows the patient can fill out questionnaires to find out how affected he/she is, detect changes in his/her condition and even evaluate the response to the interventions performed. These people are known as proxies. This research sought to assess which questionnaires for measuring depression, anxiety, neurocognitive impairment, quality of life, function, or disability can be answered by a proxy, when patients cannot answer for themselves. For this, the medical literature published on this subject was reviewed. Twenty studies showing a good agreement between the responses of the patients and the proxies were found, especially in the assessment of quality of life and functional capacity. The use of a proxy can help avoid the omission of responses.

Key words: Proxy, Health-Related Quality of Life, HRQoL, Depressive Disorder, Anxiety Disorders, Neurocognitive Disorders.

Citation: J Rehabil Med 2023; 55: jrm4493. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v55.4493

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Apr 19, 2023; Published: Jun 30, 2023

Correspondence address: María Alejandra Spir, Health Rehabilitation Group, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. E-mail: maria.spir@udea.edu.co

The evaluation of the health status of patients is essential to provide a reference measure that allows quantifying the variations over time, related to the progression of the disease or to the clinical interventions that are carried out (1). Currently, the evaluation of the perception that patients have of their health is carried out with instruments called Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs), which complement the traditional measures of morbidity and mortality. These measures reflect how individuals feel and function in their daily lives and contain important aspects for patients (2, 3).

Many PROs instruments have been reported in the literature that assesses general health status, Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), functioning, depressive or anxious symptoms, and neurocognitive impairment in different populations. Most of these instruments are completed in a self-reported way (3–5).

Ideally, when applying an instrument or a survey on the state of health and HRQoL, the patients themselves are the most appropriate to respond; however, in some patients, their disease or comorbidities do not allow them to provide information on their health status, which makes it difficult to obtain data. In some cases, it is even not possible to obtain it, such as in patients with cognitive impairment caused by stroke, multiple sclerosis, head trauma, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or in elderly people and critically ill patients (1, 3, 6).

Due to the above, the question has been raised about whether it is reliable to use alternative sources of information, as a proxy of the patient, for the application of different instruments, in scenarios in which they cannot be completed by the patient (3, 6, 7). Currently, the proxy administered the instrument completely, without the patient being present. This reduces the non-response bias and missing data attributable to limitations in the ability of patients to respond for themselves (2, 8).

In major Medicare surveys in the United States, proxy responses constituted between 10% and 30% of all responses (9). However, the results reported by proxy may be systematically different from those obtained directly from patients. The response bias of the proxy is the difference between the responses of the proxy and those of the patients, and it is a major concern for researchers.

It has been suggested that the use of alternative information, such as that provided by proxy, is preferable to assess objective signs, such as physical function and mobility. In the case of symptoms perceived by the patient, such as mood and emotional functioning, the agreement between patients and proxies is weaker due to its subjectivity (5). In general, proxy appear to provide better responses to more objective than subjective information (3, 4).

Given the important role of proxy for study populations that have difficulty completing self-report instruments, it is important to assess the degree of concordance of the proxy’ responses with those of the patients themselves and to measure any bias that may be present (4).

The objective of this study was to evaluate the concordance, correlation, and reliability of instruments for measuring HRQoL, functioning, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and cognitive impairment, when such instruments can be completed by a proxy.

METHODS

A systematic review of the literature was performed, which was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022318799) and reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Search strategy

A systematic search was performed in PUBMED, BIREME-LILACS, OVID (Cochrane), and Science Direct, Embase with the terms: Short Form-36, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, WHODAS 2.0, Patient Health Questionnaire 9, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Disability Rating Scale, Proxy, with their respective medical subject title (MeSH) and synonyms. Searches were conducted between September 2020 to October 2020 and updated in July 2021. Only Spanish or English language articles were included. The entire search strategy can be found in Appendix S1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In this review, we included studies that evaluated adult patients with any condition, to whom any of the following scales had been applied: For HRQoL, the Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36); for functioning, the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHO-DAS 2.0) and the Disability Rating Scale (DRS); for depressive and anxiety symptoms, the Patient Health Questionnaire- 9 (PHQ-9) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and for neurocognitive status, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

The selection of these assessment instruments for this systematic review was based on the difficulties observed in evaluating a series of outcomes in a cohort study of patients with traumatic brain injury aimed at establishing the factors associated with the occupational reinstatement of these patients.

It was also a criterion that the scale had been filled out by both (the patient and a proxy) and that they presented the scores or statistical measures for comparison. Articles in which the instrument filled out by the patient is not the same as the one filled out by the proxy to assess the outcome, as well as articles written in a language other than Spanish or English, were excluded from this review (10–15).

Identification and extraction of studies

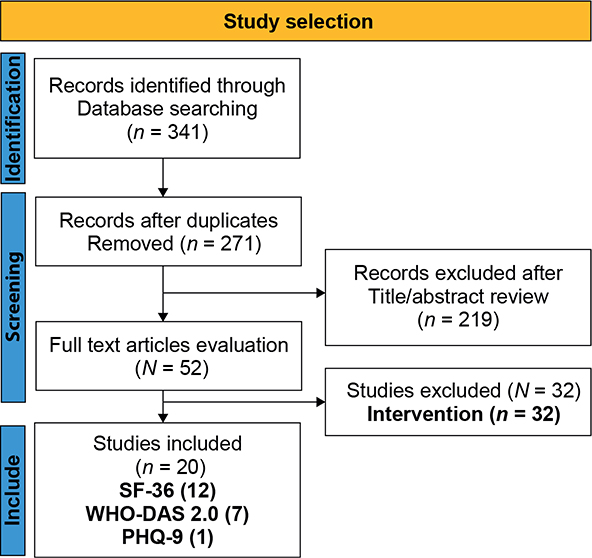

After removing duplicates, a total of 271 articles were identified. The articles were then selected by title and abstract. Each article was independently reviewed by two evaluators (MAS, JDH). Conflict of opinion regarding article selection occurred in 45 articles, which was resolved by a third evaluator (AMP). Once this first selection was completed, a total of 52 articles were obtained and two independent evaluators (MAS, JDH) reviewed the full texts of the 52 selected articles and a third evaluator (AMP) resolved the conflicts. Finally, 20 articles that met the inclusion criteria were selected (Appendix S2).

Data extraction was carried out by two researchers (JDH, MAS). Collected data included author and year of publication, title, journal, country, objective of the study, population and health condition, instruments used, results, conclusions, and quality review. In addition, a table was made for the 32 articles excluded and the reason for their exclusion. The table with the characteristics of the included and excluded studies is found in Appendix S2.

Quality evaluation

Since the included articles were cross-sectional and cohort studies, the evaluation of the quality of the reviews was carried out independently by two reviewers with the tools developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) “Checklist for Cohort Studies” and “Checklist for Cross-Sectional Studies” (16). These checklists consist of 11 or 8 questions, respectively, each of which must be answered as “yes”, “no”, “uncertain” or “not applicable”. For each review, a mean score was provided. The quality assessment score was not used as a criterion for excluding articles.

We used JBI checklists for quality evaluation because the included studies were only observational studies with different designs (Cross-sectional and cohort) so we decided to use a single tool that could assess these two types of designs. The quality evaluations of each article are described in detail in Appendix S4 (cohort evaluation) and Appendix S3 (cross sectional evaluation).

Evidence synthesis

Concordance and reliability of responses between the patients and their proxy were measured with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Cohen’s d statistic. The ICC measures the proportion of the total variability due to the variability between the responses of the groups evaluated, patients and proxy (17). Cohen’s d quantifies the magnitude of the mean difference between the responses of patients and their proxy and was calculated when data became available (18).

ICC values ≤ 0.4 represent poor reliability; values between 0.41 and 0.70 represent moderate to good reliability and values > 0.70 represent excellent reliability (19). Cohen’s d was categorized as follows: 0.0 – 0.19: minimal effect, 0.20 – 0.49: small effect, 0.50 – 0.79: Medium effect and ≥ 0.8: large effect (20). In this analysis, what is sought are minimum or small effect sizes, which indicates a smaller difference between the responses given by the patient when compared to the responses obtained from the proxy.

RESULTS

Description of the studies

Fifty-two studies were found and 32 were excluded because they did not evaluate the same instrument between the patient and the proxy or there was no measure of the correlation between the responses of both groups. Of the 20 studies included, 12 articles were from the SF-36 scale, seven from WHODAS 2.0, one from PHQ-9 (See figure 1), and no articles were found related to the STAI, DRS, and MoCA instruments (See table 1). These 20 articles were then categorized by health conditions. Ten articles were found related to neurological conditions (21–30), three with psychiatric conditions (31–33), three on the elderly (3, 4, 34), two about heart conditions (1, 35), one in intensive care unit (ICU) patients (36) and one in relation to other conditions (6) (See Table 1).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of the literature search and selection of articles. SF-36: Short Form-36; WHO-DAS 2.0: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9.

| Condition | Specific condition | Instrument | n |

| Neurological (n = 10) | Huntington’s disease (26) | WHODAS 2.0 | 1 |

| People with disabilities (24) | SF-36 | 1 | |

| Stroke (27, 30) | PHQ-9/WHODAS 2.0 | 2 | |

| Alzheimer’s disease (22) | SF-36 | 1 | |

| Dementia (23) | SF-36 | 1 | |

| Multiple sclerosis (21) | SF-36 | 1 | |

| Spinal cord injury (28, 29) | WHODAS 2.0 | 2 | |

| Brain trauma (ECT) (25) | WHODAS 2.0 | 1 | |

| Psychiatric (n = 3) | Schizophrenia (32) | WHODAS 2.0 | 1 |

| Bipolar disorder/schizophrenia (31) | SF-36 | 1 | |

| Mental illness (33) | WHODAS 2.0 | 1 | |

| Older adults (n = 3) | Older adults (3, 4, 34) | SF-36 | 3 |

| Heart disease (n = 2) | Heart disease (1, 35) | SF-36 | 2 |

| ICU patients (n = 1) | ICU patients (36) | SF-36 | 1 |

| Other conditions (n = 1) | No specific disease (6) | SF-36 | 1 |

| ICU: intensive care unit; SF-36: Short Form-36; WHO-DAS 2.0: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9. | |||

| Population/author | Patient – proxy (N) | Intraclass correlation coefficient (confidence interval) | |||||||||

| (PF) | (RP) | (BP) | (MH) | (RE) | (SF) | (VT) | (GH) | MHS | PHS | ||

| Neurological condition | |||||||||||

| Alzheimer’s disease Novella, 2006 (22) | Patients n = 70/Family proxy n = 63 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.30 | ||

| Patients N = 125/ Keeper proxy n = 63 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.42 | |||

| Dementia Novella, 2001 (23) | Patients/family proxy n = 125 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.25 | ||

| Patients/keeper proxy n = 125 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.33 | |||

| Multiple sclerosis Solari, 2001 (21) | Patient/family proxy (n = 243) | 0.91* (0.87/0.95) | 0.78* (0.72/0.83) | 0.84* (0.79/0.89) | 0.84* (0.80/0.87) | 0.66* (0.58/0.73) | 0.73* (0.67/0.78) | 0.79* (0.75/0.83) | 0.49 (0.41/0.58) | ||

| People with disabilities Andresen, 2001 (24) | Patient/best proxy available (n = 131) | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.54 |

| Patients/relative proxy (n = 78) | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.61 | |

| Patients/proxy friends (n = 32) | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.61 | |

| Patients/proxy health caregiver (n = 34) | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.22 | |

| Psychiatric condition | |||||||||||

| Schizophrenia Kim, 2010 (31) | Patient – Schizophrenia proxy (n = 77) | 0.5 (0.3/0.7) | 0.6 (0.4/0.8) | 0.6 (0.4/0.8) | 0.6 (0.4/0.8) | 0.4 (0.2/0.6) | 0.4 (0.1/0.6) | 0.4 (0.0/0.6) | 0.5 (0.2/0.7) | 0.6 (0.3/0.7) | 0.7 (0.5/0.8) |

| Bipolar disorder Kim, 2010 (31) | Patient – proxy D. Bipolar (n = 50) | 0.6 (0.3/0.8) | 0.6 (0.3/0.8) | 0.8* (0.6/0.9) | 0.6 (0.2/0.8) | 0.6 (0.3/0.8) | 0.8* (0.6/0.9) | 0.3 (–0.4/0.6) | 0.4 (0.1/0.7) | 0.6 (0.2/0.8) | 0.7 (0.4/0.8) |

| Heart disease | |||||||||||

| Heart disease Elliot, 2015 (1) | Presurgical – proxy (n = 96) | 0.75 * | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 0.7 |

| Hospital discharge (n = 77) | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.64 | 0.72* | |

| 6 months after discharge (n = 69) | 0.81* | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.80* | 0.75* | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 0.80* | |

| Older adults | |||||||||||

| Older adults with disabilities Pierre, 1998 (3) | Patient/health professional (n = 41) | 0.38 (0.12/0.58) | 0.08 (–0.18/0.3) | 0.42 (0.19/0.61) | 0.41 (0.18/0.61) | 0.13 (–0.13/0.3) | 0.01 (–0.24/0.2) | 0.60 (0.41/0.74) | 0.36 (0.12/0.56) | ||

| Patient/proxy (n = 22) | 0.55 (0.26/0.76) | 0.40 (0.05/0.68) | 0.57 (0.27/0.78) | 0.11 (–0.49/0.2) | 0.44 (0.10/0.69) | 0.19 (–0.15/0.5) | 0.11 (–0.25/0.4) | 0.58 (0.30/0.78) | |||

| Patient/health professional (n = 38) | 0.45 (0.18/0.67) | 0.09 (–0.15/0.3) | 0.39 (0.15/0.59) | 0.41 (0.17/0.61) | 0.23 (–0.03/0.4) | 0.11 (–0.15/0.3) | 0.11 (–0.16/0.3) | 0.43 (0.19/0.62) | |||

| Patient/proxy (n = 19) | 0.71* (0.28/0.87) | 0.03 (–0.42/0.3) | 0.21 (–0.20/0.5) | 0.52 (0.19/0.75) | 0.18 (–0.21/0.5) | 0.01 (–0.37/0.3) | 0.40 (0.03/0.68) | 0.33 (0.01/0.61) | |||

| Older adults with disabilities Ball, 2001 (34) | Patient/professional proxy (n = 164) | 0.600 | 0.066 | 0.690 | 0.579 | 0.320 | 0.333 | 0.419 | 0.344 | ||

| Patient/layman proxy (n = 164) | 0.262 | 0.102 | 0.507 | 0.335 | 0.204 | 0.275 | 0.244 | 0.308 | |||

| Older adults Yip, 2001 (4) | Patient – proxy (n = 32) | 0.842* | 0.502 | 0.307 | 0.445 | 0.318 | 0.380 | 0.484 | 0.688 | 0.423 | 0.65 |

| SF-36 domains: PF: physical functioning; RP: role physical; BP: bodily pain; MH: mental health; RE: role emotional; SF: social functioning; VT: vitality; GH: general health; PHS: Physical Health Summary; MHS: Mental Health Summary. ICC ≤ 0.40 = poor level of agreement. ICC 0.41–0.70 = Moderate level of agreement. *ICC ≥ 0.71 = Excellent level of agreement. | |||||||||||

| ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient. | |||||||||||

| Population, Author | Effect size: Cohen’s d (confidence interval) | |||||||||

| (PF) | (RP) | (BP) | (MH) | (RE) | (SF) | (VT) | (GH) | MHS | PHS | |

| Neurological condition | ||||||||||

| Novella, 2006 (22). Alzheimer’s disease | 0.50 (0.15/0.84) | 0.07 (–0.27/0.41) | 0.20 (–0.14/0.55) | 0.23 (–0.11/0.58) | 0.05 (–0.29/0.39) | 0.56 (0.20/0.90) | 0.26 (–0.08/0.60) | 0.23 (–0.11/0.58) | ||

| Psychiatric condition | ||||||||||

| Kim, 2010 (31). Schizophrenia | 0.28 (–0.22/0.78) | 0.05 (–0.44/0.55) | 0.01 (–0.49/0.51) | 0.01 (–0.49/0.50) | 0.00 (–0.5/0.5) | 0.12 (–0.38/0.61) | 0.07 (–0.43/0.57) | 0.01 (–0.49/0.51) | 0.04 (–0.46/0.54) | 0.05 (–0.44/0.55) |

| Kim, 2010 (31). Bipolar disorder | 0.51 (–0.11/1.13) | 0.09 (–0.52/0.70) | 0.10 (–0.51/0.71) | 0.01 (–0.60/0.62) | 0.20 (–0.41/0.81) | 0.04 (–0.56/0.66) | 0.35 (–0.26/0.97) | 0.22 (–0.39/0.83) | 0.31 (–0.31/0.92) | 0.38 (–0.23/1.00) |

| Heart disease | ||||||||||

| Fast, 2009 (35). Heart disease | 0.19 (–0.24/0.62) | 0.12 (–0.30/0.55) | 0.14 (–0.29/0.57) | 0.39 (–0.04/0.82) | 0.05 (–0.38/0.48) | 0.18 (–0.25/0.61) | 0.45 (0.02/0.89) | 0.05 (–0.37/0.48) | 0.25 (–0.17/0.69) | 0.12 (–0.31/0.54) |

| Older adults | ||||||||||

| Pierre, 1998 (3). Older adults | 0.48 (0.13/0.84) | 0.12 (–0.22/0.47) | 0.05 (–0.29/0.40 | 0.00 (–0.35/0.35) | 0.05 (–0.29/0.41) | 0.31 (–0.04/0.66) | 0.22 (–0.13/0.58) | 0.17 (–0.18/0.52) | ||

| Yip, 2001 (4). Older adults | 0.19 (–0.30/0.68) | 0.04 (–0.45/0.53) | 0.36 (–0.13/0.86) | 0.52 (0.02/1.01) | 0.13 (–0.36/0.62) | 0.27 (–0.22/0.77) | 0.20 (–0.29/0.69) | 0.34 (–0.15/0.84) | 0.36 (–0.13/0.86) | 0.19 (–0.30/0.69) |

| Others | ||||||||||

| Hofhuis, 2003 (36). ICU patients | 0.24 (–0.02/0.50) | 0.18 (–0.08/0.44) | 0.18 (–0.08/0.44) | 0.16 (–0.11/0.42) | 0.08 (–0.18/0.34) | 0.26 (0.00/0.53) | 0.16 (–0.10/0.42) | 0.43 (0.17/0.70) | ||

| Ellis, 2003 (6). No specific condition | 0.17 (0.12/0.21) | 0.06 (0.01/0.10) | 0.02 (–0.03/0.07) | 0.08 (0.04/0.13) | 0.14 (0.10/0.19) | 0.15 (0.10/0.20) | 0.17 (0.12/0.22) | 0.11 (0.06/0.16) | 0.02 (–0.03/0.07) | 0.11 (–0.11/0.15) |

| “Cohen’s d”: 0.0 – 0.19: Minimal effect, 0.20–0.49: Small effect, 0.50–0.79: Medium effect, > 0.8: Large effect. SF-36 domains: PF: physical functioning; RP: role physical; BP: bodily pain; MH: mental health; RE: role emotional; SF: social functioning; VT: vitality; GH: general health; PHS: Physical Health Summary; MHS: Mental Health Summary: ICU: intensive care unit. | ||||||||||

Of the 20 articles included, 14 were cross-sectional studies and 6 were cohort studies. The study quality was variable. There were 13 studies considered to be of moderate to good quality (score greater than 4/8 for cross-sectional studies or greater than 6/11 for cohort). Regarding the cross-sectional studies, it was found that the greatest flaw was in points 5 and 6 of the JBI instrument, which corresponded to the confounding factors. Most of the studies did not take into account factors that could create bias in the presence of some difference between the groups, for example, the time that the proxy spent with the patient, if they were close, if they lived together or the frequency of visits to the patient.

SF-36 Patient – Proxy

In multiple sclerosis, all the domains presented an agreement between moderate to excellent, the domain that showed the highest reliability was the physical functioning (PF) with an ICC = 0.91 (95% CI = 0.87 – 0.95) (21). In patients with Alzheimer’s, role physical (RP) was the one with the highest concordance with an effect size d = 0.07 (95% CI = – 0.27 – 0.41), and social functioning (SF) was the one with the lowest concordance level d = 0.56 (95% CI = 0.20 – 0.90) (22).

In patients with dementia, all the domains have a poor level of agreement in the answers provided by the patients when compared with those of the family and caregiver proxy. Although there was no moderate correlation in any domain, the PF was the domain with the highest agreement with an ICC = 0.39 and in the SF, there was no degree of agreement between the patient and the caregiver (23).

In a group of people with disabilities, including some patients with multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and traumatic brain injury, there were different types of proxy (best available proxy, family, friends, and health personnel). PF, bodily pain (BP), mental health (MH), and general health (GH) obtained moderate agreement with all types of proxy. On the contrary, the RP, the role emotional (RE), and the SF were dimensions that showed a poor level of agreement (24).

In the studies that included patients with psychiatric conditions, it was found that, in schizophrenia, when comparing the responses between patients and proxy, in general, all the dimensions had a poor to moderate agreement, the summary of physical components was the one that showed higher reliability with an ICC = 0.7 (95% CI = 0.5 – 0.8) followed by the PF, BP and MH domains. When analyzed by effect sizes with Cohen’s d, all the domains and the summary of components present a small difference between the responses of the patients and the proxy, with the Role Emotional (RE) having the smallest difference with a d= 0.00 (95% CI = – 0.5 – 0.5) which means a very good concordance between both answers (31).

In patients with bipolar affective disorder (BAD), the agreement between patients and proxy is moderate to good in all dimensions, except for the dimension of vitality (VT) ICC = 0.3. The dimensions with the greatest agreement were the BP with ICC=0.8 and the SF with ICC = 0.8 and when evaluating effect sizes in the differences between both groups, the SF domain was also the one that showed the least difference with a d = 0.04 (95% CI = – 0.56 – 0.66), the MH had the highest agreement with d = 0.01 (95% CI = – 0.60 – 0.62) (31).

In cardiac surgery patients, the agreement between patients and proxy showed that BP dimension and VT had a poor agreement, and these were correlated with time (follow-up from before surgery to 6 months after) (1). However, this study showed at 6-month follow-up that concordance was higher in the PF, RF, and MH domains, as well as in the Physical Health Summary (PHS) (1).

In patients who are in phase II cardiac rehabilitation programs, when comparing the responses in HRQoL improvement reported by the patient with those of their spouse, RE and GH were the domains with the highest agreement with d = 0.05 (– 0.37 – 0.48) in both groups (35).

In a population of older adults, the correlation between patient/health personnel and the patient/proxy correlation indicated a poor concordance in the SF, in the two scenarios evaluated: outpatient and inpatient rehabilitation services (3). There was excellent agreement on none of the dimensions. The dimension with the best patient/proxy agreement was the PF with ICC = 0.55 (95% CI = 0.26 – 0.76), patient/health professional was ICC= 0.45 (95% CI = 0.18 – 0.67), and patient/proxy in day hospital setting ICC = 0.71 (95% CI = 0.28 – 0.87) (3).

In a group of elderly people with physical disabilities who evaluated the concordance between the patient/health personnel and the patient/reference person, when evaluating HRQoL with the SF-36, it was found that the BP dimension had the greatest concordance with an ICC = 0.69 followed by the PF with an ICC = 0.6 (9). The dimensions RE and SF had a poor agreement in the two types of proxy. Patient and proxy mean scores for all 8 domains of the SF-36 were lower for proxy than patient scores, except for the RP dimension. The mean scores of the professional representatives in the eight dimensions of the SF-36 were closer to the estimates of the patients (9).

In another study where the correlation in the responses of the SF-36 in older adults was evaluated, the best concordance was obtained in the PF with ICC=0.84 and in the RP when the effect size was evaluated with a d = 0.04 (95% CI = – 0.45 – 0.53) while the domains with the poorest concordance were BP with ICC = 0.30, DE with ICC=0.31 and SF with ICC=0.38, as well as MH with d = 0.52 (95% CI = 0.02 – 1.01) (4).

When the SF-36 instrument is filled out by a proxy, it can reliably assess the HRQoL of critically ill patients upon admission to the ICU, the RE was the one with the highest agreement with d = 0.08 (95% CI = – 0.18 – 0.34) and the domain with the lowest agreement was GH with d = 0.43 (95% CI = 0.17 – 0.70) (36).

In a Medicare review that included more than 65,000 proxy responses from patients with various medical conditions, all domains of the SF-36 had a small effect size when comparing patient means to proxy responses, which means an excellent concordance in the responses of both groups, with summary values of the mental component d = 0.02 (95% CI = – 0.03 – 0.07) and of the physical component and d = 0.11 (95% CI = – 0.11 – 0.15). For the domains of PF, VT, SF, and RE a moderate effect size was found, and for the other domains a small effect size (6).

WHODAS 2.0 Patient – Proxy.

Of the seven articles included in WHODAS 2.0, five were related to neurological conditions such as spinal cord injury, stroke, traumatic brain injury, and Huntington’s disease (26 – 30), and two are related to psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia and other mental disorders (32, 33). The concordance evaluation in these studies was carried out by measuring the effect size with the mean difference with the “Cohen’s d” (See Table 4).

| Author | Population | Cohen’s d (confidence interval) |

| Neurological condition | ||

| Tarvonen-Schröder 2019 (28) | Spinal cord injury | 0.67 (0.30–1.03) |

| Chronic back pain | 1.92 (1.44–2.41) | |

| Tarvonen-Schröder 2019 (29) | Spinal cord injury | 0.11 (–0.42–0.65) |

| Tarvonen-Schröder 2018 (25) | TEC | 0.02 (–0.24–0.28) |

| Downing 2014 (26) | Huntington’s disease | 0.18 (–0.02–0.39) |

| Psychiatric condition | ||

| Zhou 2020 (33) | Mental disorders | 0.05 (–0.16–0.26) |

| Pietrini 2021 (32) | Schizophrenia | 0.01 (–0.46–0.47) |

| “Cohen’s d”: 0.0–0.19: Minimal effect, 0.20–0.49: small effect, 0.50–0.79: medium effect, > 0.8: large effect. | ||

In general, in neurological conditions, a small effect size was found in the total values of the WHODAS 2.0, which means that there is a larger concordance between the patient’s evaluations when compared to those applied by the proxy, mainly in patients who suffered a stroke (25) with a d = 0.02 (95% CI = – 0.24 – 0.28) and in patients with Huntington’s disease (26) with a d = 0.18 (95% CI = – 0.02 – 0.39). Of the two studies that evaluated patients with spinal cord injury, no similar results were found in terms of concordance, however, one of the articles referred to tetraplegic patients while in the other study the type and level of the injury were more variable. In patients with tetraplegia a good concordance was found between patient and proxy d = 0.11 (95% CI = – 0.42 – 0.65) (29). The only group of all studies included regarding the WHODAS 2.0 that showed a large difference in effect size was the chronic back pain group, with worse concordance between the responses of the patient and that of the proxy with a d = 1.92 (95% CI = 1.44 – 2.41), whit latter being the one that perceives the greatest alteration in functioning above the perception of the patient himself (28).

In psychiatric conditions, two articles were included about patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders, among others (32, 33). In the group of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (32), when evaluating the size of the effect between the responses of the patient and the proxy, a good correlation was found in the responses of the WHODAS 2.0 in its global score with a d = 0.01 (95% CI = – 0.46 – 0.47). Similarly, in the group with different diagnoses of mental disorders with a d = 0.05 (95% CI = – 0.16 – 0.26) (33).

PHQ-9 Patient – Proxy

Only one study was found that met the objective of this review (35). The study evaluated the validity and responsiveness of the proxy compared to the responses of the patients. This cross-sectional study included 200 stroke patients. The PHQ-9 reported by the patient had a score of 6.0 (± 4.9) and that of the proxy had 7.0 (± 5.4), with an effect size of d = 0.19 (95% CI = 0 – 0.39 ), with a good agreement between the responses of the patient and those of the proxy. Finally, this study concludes that the use of responses obtained by proxy in patients with stroke with more than three months of evolution is justified (30).

DISCUSSION

Different instruments for the evaluation of the HRQoL, functioning, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and neurocognitive impairment are widely validated in the literature, but there are still some difficulties in their application, as in the case when they cannot be completed by the patient and alternative methods must be used to obtain this information, such as the application of the same instrument by a proxy, caregiver, family member or health personnel. Although some of the instruments are designed to be applied by both patients and proxy, there are others in which this has not been validated.

The selection of these assessment instruments for this systematic review was based on the difficulties observed in evaluating a series of outcomes in a cohort study of patients with traumatic brain injury aimed at establishing the factors associated with the occupational reinstatement of these patients.

The SF-36 and WHODAS 2.0 are the instruments that provided the most results for the analysis; on the contrary, no results were obtained with the STAI, DRS, and MoCA instruments. About the STAI, two articles evaluated in children were found that aimed to validate modifications of this scale to be applied to parents or proxy, however, in general, there was not a good level of agreement between children and their parents with these modified scales (37). The lack of results of the DRS can be explained by the characteristics of the instrument itself where the objectivity of the instrument does not affect its reliability whoever fills it out. In contrast, the MoCA, being a cognitive assessment instrument, cannot be completed by a proxy of the patient and the result of the instrument must be established with what the patient has been able to answer (11, 13).

In the evaluation of HRQoL, it was found that the domains that evaluate the physical component, mainly in neurological conditions are the ones that show the highest level of agreement and greater precision. On the contrary, a greater disagreement was found in the domains of the mental component and in the SF. This result coincides with what has been described in the literature, and that is that there is greater patient/proxy concordance in the domains or elements that are more visible and observable, such as the physical component. In contrast, the less observable and more subjective domains and elements such as the social, environmental, and self-perception domains have less concordance in patient/proxy responses (6).

When comparing the SF-36 with other instruments that assess HRQoL such as the WHOQoL-BREF in neurological conditions such as head trauma, it is found that with this instrument the level of concordance proxy/patient was adequate, having a greater level of agreement the domain of physical functioning than the domains that evaluate social aspects and self-perception. Additionally, it is described that the age of the patient, the severity of the injury, and the relationship of the proxy with the patient can affect the level of agreement (38).

The results obtained with the WHODAS 2.0, a generic tool that measures activities and participation with more objective questions for the patient and the proxy (25), found very good reliability between patient/proxy responses in neurological and psychiatric conditions.

In a study in patients who suffered a stroke (39), the response was evaluated in both patients and proxy of the modified Rankin (strength) (40), Barthel index (activities of daily living) (41), Lawton assessment (instrumental activities of daily living) (42), Folstein Mini Mental State Examination (cognition) (43), and the SIS (Stroke Impact Scale) (44) and found that the indirect bias towards overestimation of the severity of the patient’s condition tended to increase as the severity of the stroke increased, but when evaluating the effect size between the responses given by the patient and those given by the proxy were small (range, -0.1 to 0.4) with an intraclass correlation coefficient that was between 0.50 and 0.83. They also clarify that the degree of agreement was better for the observable physical domains.

Regarding to the PHQ-9 instrument, only one article was found, in this study the instrument was compared between stroke patients and their proxy, with a good concordance in the responses of both groups (30). However, as it is a single study included in the evaluation of this instrument, it is not possible to define if this instrument is applicable to any population with the possibility of reproducing the same results and reliability.

This review provides important results to clinicians, researchers, and health professionals, in general, to evaluate the HRQoL and functioning outcomes through the responses to the instruments by the proxy when they cannot be completed by the patients. For this reason, there could be greater reliability, fewer data losses attributable to limitations in the ability of patients to respond for themselves, better control of bias in research, and more comprehensive assessments in clinical practice of patients in a most serious health condition (9).

Limitations

The lack of inclusion of other instruments that evaluate the same outcomes assessed in this review may limit the generalizability of the results only to HRQoL or functioning instruments. There could be specific instruments with a greater possibility of agreement of the outcomes reported by the patient and by the proxy, but a greater number of studies with these characteristics are needed.

This review would have been more precise if the focus had been on a single health condition. However, due to the lack of proxy information, it was decided to carry out the systematic review including all health conditions.

In most studies where the level of agreement was evaluated with the ICC, the confidence interval was not included, which is important to better define the precision of the results. Furthermore, the methodological quality of the primary studies included, the lack of sample size calculations, and the variability of their correlation measures affected the interpretation of the results obtained.

Another limitation of this study was the selection of the assessment instruments for this systematic review, due to the fact that they were chosen based on the difficulties observed in patients with traumatic brain injury in a cohort study.

Implications for practice

The use of alternative sources to obtain information, as a proxy, becomes a feasible solution to non-response and missing data attributable to limitations in the ability of patients to respond for themselves in clinical settings.

Using evaluation instruments that allow the use of proxy to answer them when the patient cannot do so, facilitates, and improves the quality of the data in an investigation by better controlling the biases associated with incomplete data.

It is important that in the validation processes of an instrument the component of the evaluation by proxy be included, for those situations in which the patients have limitations to respond

Rehabilitation hospitals that use HRQoL and functioning outcomes benefit from the results of this research because it will allow them to better understand which instruments and which domains can be used in the evaluation of patients and in their follow-up, and in this way improve intervention programs.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the levels of agreement between the responses of the patients and the proxy were good, mainly when evaluating HRQoL and functioning with the SF-36 and WHODAS 2.0 instruments, respectively, with a higher level of agreement in the more objective and observable domains such as physical functioning and lower level of agreement in less objective domains, such as emotional or affective status, and self-perception. In patients who cannot fill out the different instruments, the use of a proxy can helps avoid the omission of responses and facilitate decision-making in clinical practice by having more comprehensive and complete information about the effects of an intervention or the evolution of a given health condition.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and have received no funding for this study.

REFERENCES

- Elliott D, Lazarus R, Leeder SR. Proxy respondents reliably assessed the quality of life of elective cardiac surgery patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59: 153–159. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.06.010.

- Andresen EM, Vahle VJ, Lollar D. Proxy reliability: Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures for people with disability. Qual Life Res 2001; 10: 609–619. DOI: 10.1023/a:101318790359

- Pierre U, Wood-Dauphinee S, Korner-Bitensky N, Gayton D, Hanley J. Proxy use of the Canadian SF-36 in rating health status of the disabled elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 983–990. DOI: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00090-0.

- Yip JY, Wilber KH, Myrtle RC, Grazman DN. Comparison of older adult subject and proxy responses on the SF-36 health-related quality of life instrument. Aging Ment Health 2001; 5: 136–142. DOI: 10.1080/13607860120038357.

- Rooney AG, McNamara S, Mackinnon M, Fraser M, Rampling R, Carson A, et al. Screening for major depressive disorder in adults with glioma using the PHQ-9: a comparison of patient versus proxy reports. J Neurooncol 2013; 113: 49–55. DOI: 10.1007/s11060-013-1088-4.

- Ellis BH, Bannister WM, Cox JK, Fowler BM, Shannon ED, Drachman D, et al. Utilization of the propensity score method: an exploratory comparison of proxy-completed to self-completed responses in the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003; 1: 47. DOI: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-47.

- Davin B, Joutard X, Paraponaris A. “If you were me”: proxy respondents’ biases in population health surveys. Research Papers in Economics 2019.

- Elliott MN, Beckett MK, Chong K, Hambarsoomians K, Hays RD. How do proxy responses and proxy-assisted responses differ from what Medicare beneficiaries might have reported about their health care? Health Serv Res 2008; 430: 833–848. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00820.x.

- Li M, Harris I, Lu ZK. Differences in proxy-reported and patient-reported outcomes: assessing health and functional status among Medicare beneficiaries. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015; 15: 62. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-015-0053-7.

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483.

- MoCA Test. MoCA – cognitive assessment. 2019 [cited 2022 Apr 18]. Available from: https://www.mocatest.org/the-moca-test/

- WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Who.int. [cited 2022 Apr 18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health/who-disability-assessment-schedule

- Disability Rating Scale. Tbims.org. [cited 2022 Apr 18]. Available from: https://www.tbims.org/combi/drs/

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–613. DOI: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

- Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011; 63: S467–S472. DOI: 10.1002/acr.20561.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools. 2017 [cited 2022 Jun 8]. Available from: https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools

- Prieto L, Lamarca R, Casado A. [Assessment of the reliability of clinical findings: the intraclass correlation coefficient]. La evaluación de la fiabilidad en las observaciones clínicas: el coeficiente de correlación intraclase. Med Clin (Barc) 1998; 110: 142–145.

- Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen 2012; 141: 2–18. DOI: 10.1037/a0024338.

- Hair JF, Celsi M, Celsi MW, Money A, Samouel P, Page M. The essentials of business research methods. 3rd edn. London: Routledge; 2016.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1977.

- Solari A, Radice D. Health status of people with multiple sclerosis: a community mail survey. Neurol Sci 2001; 22: 307–315. DOI: 10.1007/s10072-001-8173-8.

- Novella JL, Boyer F, Jochum C, Jovenin N, Morrone I, Jolly D, et al. Health status in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: an investigation of inter-rater agreement. Qual Life Res 2006; 15: 811–819. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-005-5434-7.

- Novella JL, Jochum C, Ankri J, Morrone I, Jolly D, Blanchard F. Measuring general health status in dementia: practical and methodological issues in using the SF-36. Aging (Milano) 2001; 13: 362–369. DOI: 10.1007/BF03351504.

- Andresen EM, Vahle VJ, Lollar D. Proxy reliability: health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures for people with disability. Qual Life Res 2001; 10: 609–619. DOI: 10.1023/a:1013187903591.

- Tarvonen-Schröder S, Tenovuo O, Kaljonen A, Laimi K. Usability of World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule in chronic traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med 2018; 50: 514–518. DOI: 10.2340/16501977-2345.

- Downing NR, Kim JI, Williams JK, Long JD, Mills JA, Paulsen JS; PREDICT-HD Investigators and Coordinators of the Huntington Study Group. WHODAS 2.0 in prodromal Huntington disease: measures of functioning in neuropsychiatric disease. Eur J Hum Genet 2014; 22: 958–963. DOI: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.275.

- Tarvonen-Schröder S, Hurme S, Laimi K. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) and the WHO Minimal Generic Set of Domains of Functioning and Health versus conventional instruments in subacute stroke. J Rehabil Med 2019; 51: 675–682. DOI: 10.2340/16501977-2583.

- Tarvonen-Schröder S, Kaljonen A, Laimi K. Comparing functioning in spinal cord injury and in chronic spinal pain with two ICF-based instruments: WHODAS 2.0 and the WHO minimal generic data set covering functioning and health. Clin Rehabil 2019; 33: 1241–1251. DOI: 10.1177/0269215519839104.

- Tarvonen-Schröder S, Kaljonen A, Laimi K. Utility of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule and the World Health Organization minimal generic set of domains of functioning and health in spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Med 2019; 51: 40–46. DOI: 10.2340/16501977-2501.

- Lapin BR, Thompson NR, Schuster A, Honomichl R, Katzan IL. The validity of proxy responses on patient-reported outcome measures: are proxies a reliable alternative to stroke patients’ self-report? Qual Life Res 2021; 30: 1735–1745. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-021-02758-9.

- Kim EJ, Song DH, Kim SJ, Park JY, Lee E, Seok JH, et al. Proxy and patients ratings on quality of life in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Korea. Qual Life Res 2010; 19: 521–529. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-010-9617-5.

- Pietrini F, Tatini L, Santarelli G, Brugnolo D, Squillace M, Bozza B, et al. Self- and caregiver-perceived disability, subjective well-being, quality of life and psychopathology improvement in long-acting antipsychotic treatments: a 2-year follow-up study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2021; 25: 307–315. DOI: 10.1080/13651501.2021.1912358.

- Zhou W, Liu Q, Yu Y, Xiao S, Chen L, Khoshnood K, et al. Proxy reliability of the 12-item world health organization disability assessment schedule II among adult patients with mental disorders. Qual Life Res 2020; 29: 2219–2229. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-020-02474-w.

- Ball AE, Russell EM, Seymour DG, Primrose WR, Garratt AM. Problems in using health survey questionnaires in older patients with physical disabilities. Can proxies be used to complete the SF-36? Gerontology 2001; 47: 334–340. DOI: 10.1159/000052824.

- Fast YJ, Steinke EE, Wright DW. Effects of attending phase II cardiac rehabilitation on patient versus spouse (proxy) quality-of-life perceptions. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2009; 29: 115–120. DOI: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31819a023c.

- Hofhuis J, Hautvast JLA, Schrijvers AJP, Bakker J. Quality of life on admission to the intensive care: can we query the relatives? Intensive Care Med 2003; 29: 974–979. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-003-1763-6.

- Shain LM, Pao M, Tipton MV, Bedoya SZ, Kang SJ, Horowitz LM, et al. Comparing parent and child self-report measures of the state-trait anxiety inventory in children and adolescents with a chronic health condition. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2020; 27: 173–181. DOI: 10.1007/s10880-019-09631-5.

- Hwang HF, Chen CY, Lin MR. Patient-proxy agreement on the health-related quality of life one year after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017; 98: 2540–2547. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.05.013.

- Duncan PW, Lai SM, Tyler D, Perera S, Reker DM, Studenski S. Evaluation of proxy responses to the Stroke Impact Scale. Stroke 2002; 33: 2593–2599. DOI: 10.1161/01.str.0000034395.06874.3e.

- van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJA, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988; 19: 604–607.

- Mahoney P. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965; 14: 61–65.

- Lawton M, Brody E. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969; 9: 179–186.

- Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini-Mental State: a practical guide for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 53: 189–198.

- Duncan PW, Wallace D, Lai SM, Johnson D, Embretson S, Laster L. The Stroke Impact Scale Version 2.0: evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke 1999; 30: 2131–2140.