ORIGINAL REPORT

EARLY OPPORTUNITIES TO EXPLORE OCCUPATIONAL IDENTITY CHANGE: QUALITATIVE STUDY OF RETURN-TO-WORK EXPERIENCES AFTER STROKE

Rachelle A. MARTIN, PhD1,2, Julianne K. JOHNS, BSc, BSLT(Hons), PG Cert HEALSCI (Clin Rehab)1, Jonathan J. HACKNEY, PhD1, John A. BOURKE, PhD1,3, Timothy J. YOUNG, MSc, PGCert EdPsych1, Joanne L. NUNNERLEY, PhD1,4, Deborah L. SNELL, PhD4, Sarah DERRETT, PhD5 and Jennifer A. DUNN, PhD4

From the 1Burwood Academy Trust, Christchurch, 2Department of Medicine, University of Otago Wellington, 3Ngāi Tahu Māori Health Research Unit, University of Otago, Dunedin, 4Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Musculoskeletal Medicine, University of Otago Christchurch and 5Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Background: Rates of return-to-work after stroke are low, yet work is known to positively impact people’s wellbeing and overall health outcomes.

Objective: To understand return-to-work trajectories, barriers encountered, and resources that may be used to better support participants during early recovery and rehabilitation.

Participants: The experiences of 31 participants (aged 25–76 years) who had or had not returned to work after stroke were explored.

Methods: Interview data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis methods within a broader realist research approach.

Results: Participants identified an early need to explore a changed and changing occupational identity within a range of affirming environments, thereby ascertaining their return-to-work options early after stroke. The results articulate resources participants identified as most important for their occupational explorations. Theme 1 provides an overview of opportunities participants found helpful when exploring work options, while theme 2 explores fundamental principles for ensuring the provided opportunities were perceived as beneficial. Finally, theme 3 provides an overview of prioritized return-to-work service characteristics.

Conclusion: The range and severity of impairments experienced by people following stroke are broad, and therefore their return-to-work needs are diverse. However, all participants, irrespective of impairment, highlighted the need for early opportunities to explore their changed and changing occupational identity.

LAY ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to understand how best to support people returning to work after a stroke. A total of 31 people who had or had not been able to return to paid work after stroke were interviewed. We listened to their experiences and considered what worked best for different people with a range of needs and aspirations. People talked about wanting opportunities soon after their stroke to explore changing thoughts about themselves and their ability to return to work. Conversations with participants and their families, often starting very early after stroke, were important. People also wanted opportunities to practise skills they typically used at work, such as social skills or planning and organizational tasks. Through these ongoing conversations and opportunities to practise, people talked about gradually regaining their confidence in the skills they had retained after their stroke, rather than focusing only on the difficulties they were experiencing.

Key words: stroke; work; employment; vocational rehabilitation; community participation; social identification; social adjustment; qualitative research.

Citation: J Rehabil Med 2023; 55: jrm00363. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v55.4825

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Nov 18, 2022; Published: Feb 7, 2023

Correspondence address: Rachelle Martin, Burwood Academy Trust, Private Bag 4708, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand. E-mail: rachelle.martin@burwood.org.nz

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Stroke is a leading cause of disability worldwide, with people of younger age increasingly being impacted (1–3). At the same time, treatments to reduce mortality and disability are increasingly effective (4, 5); hence more people of working age are experiencing stroke and there is a need to consider return-to-work (RTW) goals for this group. In New Zealand (NZ), approximately 8,000–9,000 people experience stroke yearly (5). While overall stroke incidence has decreased, Māori and Pacific populations continue to experience stroke at a significantly younger age (mean ages 60 and 62 years, respectively) compared with NZ Europeans (mean age 75 years) (6, 7).

Returning to work after illness, injury or with a long-term health condition is associated with improved health and wellbeing outcomes (8–10). Nevertheless, RTW rates for paid work remain low after stroke. Internationally, estimates of RTW rates can be as low as 19% of people working at 3 months post-stroke, reducing to 12% at 5 years, and 3% at 10 years (11). Factors influencing RTW after stroke include both non-modifiable (i.e. ethnicity, age, mental health history, education level, and pre-stroke work role) and modifiable factors (i.e. functional status, social support, workplace policies, and psychosocial resources) (11–13).

Vocational rehabilitation can support people with a new health condition to RTW (14, 15). In spinal cord injury (SCI) populations, early intervention vocational rehabilitation (EIVR) provided soon after illness or injury onset can improve RTW rates (16, 17). Evidence suggests that EIVR, beginning with informal non-pressured conversations with people with SCI about their work options, can increase confidence in ability to work, support psychological adjustment, and help people engage in solution-focused options (18, 19).

Currently within NZ, the national health service does not include comprehensive RTW services for people following stroke. Instead, depending on where they live, a small number of people after stroke can access point-in-time funded support for discrete RTW goals. Policies related to eligibility for means-tested disability benefit also contribute to their inability to access RTW services. This situation contrasts with people experiencing injury within NZ, whose rehabilitation and wage compensation are funded by a national no-fault injury insurer that funds early and ongoing vocational rehabilitation across a person’s life (20, 21).

This paper explores the experiences of people following stroke who had and had not returned to work. By reflecting on participants’ experiences, the study aimed to develop a more nuanced understanding of the RTW contexts people experience following stroke, the resources that would best support them to RTW, and how EIVR could optimize RTW goal achievement and health and wellbeing outcomes. This study is part of a larger “Early vocational rehabilitation following neurological disability study” (EVocS) project that used a 3-phase knowledge synthesis, evaluation and knowledge translation exploratory design to develop early intervention vocational services for people following stroke in NZ (18, 19, 22–24).

In this publication, the term “occupation” refers broadly to the activities that people do as individuals, in families and with communities to occupy time and bring meaning and purpose to life (including paid work), while “work” refers to paid employment. The term “vocational” is used in relation to the providers and services that support both non-paid and paid work outcomes.

METHODS

Reflexive thematic analysis methods (25) were used to collect and analyse data within a broader realist research approach (26, 27). The EVocS project, including this qualitative study, received ethics approval from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (reference: H19/170).

Inclusion criteria

Participants were over the age of 18 years and working at the time of their stroke. They were NZ residents and able to communicate in English in an interview, either with or without a support person or technology. People who had and had not returned to work were included.

Recruitment

Participants were purposively recruited via social media advertisements within healthcare provider networks. Participants were also identified via clinical and community contacts of the research team. This study sought to recruit a diverse range of participants in terms of demographics and RTW experiences; however, everyone who expressed an interest in participating was interviewed. One researcher (JJ) was provided with the names and contacts of people interested in accessing further study information, and easy-read information and consent sheets were sent to them. Those expressing interest were also individually contacted by JJ to ensure they had the study information, to answer any questions, and to check for accessibility needs. After consent had been gained, an appointment was made for the interview at a place, time and mode of the participant’s choosing; either online, at the participant’s home or in the researcher’s workplace.

Data collection

A mixture of face-to-face and online interviews were conducted by 3 researchers (JJ, JB and TY). JJ is a speech-language therapist with extensive experience supporting the communication needs of people following stroke. JB and TY live with their own experiences of disability (SCI) and conducted interviews with people living in their regional areas. All interviewers had been involved in previous phases of the EVocS study.

Demographic information related to personal, health and employment status, and living situations was collected. A semi-structured interview guide (Appendix S1) included questions about the contexts and resources that did, or potentially could have, supported future work. However, the interview questions remained flexible, with participants being encouraged to tell the stories of their stroke journeys in their own words and following their own structure. While attention was paid to what worked well for participants, particularly early after their stroke, the study also sought to gather data about unmet RTW needs and aspirations. Communication support was provided as required, including using written notes, paraphrasing to check meaning, and giving extra time. Interviews were recorded on a digital recording device, transcribed verbatim and anonymized for analysis.

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis methods (25) were used to guide the analysis of data gathered during interviews. Three researchers (RM, JJ and JH) inductively coded 7 transcripts, contributing to a coding structure developed at a face-to-face analysis meeting. RM is an experienced qualitative researcher with 20 years of experience providing rehabilitation to people following stroke, and JH is a clinical psychologist who works with people following acquired neurological conditions. RM and JH contributed to previous phases of this EVocS study. The coding structure was checked for resonance with the other interviewers (TY and JB) and the wider EVocS team, and then informed the ongoing analysis of transcripts conducted by RM, JJ and JH. A table within Microsoft Word was used to collate data that supported, refuted or refined the coding structure. Additional codes were added in response to analysis of the remaining transcripts. Researchers also added analytical comments to the table, providing additional information about how each extract contributed to the analytic process. Once all the transcripts had been analysed, JH, JJ, JB and RM met to develop an overall analytical framework. In this meeting, each researcher individually interacted with printed-out code headings to create possible theme groupings, sharing and discussing their reasoning with others. RM then synthesized these analytical thoughts to develop an overall model and worked with JJ to articulate findings within a narrative. Rigour and trustworthiness were further ensured by presenting the findings to stroke lived-experience experts, vocational providers, and healthcare professionals in knowledge translation workshops and interviews in the following phase of the EVocS study.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 31 people were interviewed (Table I). Interviews took between 36 and 132 min, and were conducted online (n = 17), on the telephone (n = 1), face-to-face in participants homes (n = 5), or at the researcher’s workplace (n = 8). Participants were in the age range 20–72 years at the time of their stroke, and were interviewed a mean of 5 years after their stroke (range 1–17 years). Most participants (91%) had an inpatient admission following their stroke. Approximately half of all participants (45%) reported receiving vocational rehabilitation. Nineteen participants (59%) were in part- or full-time employment at the time of the interview.

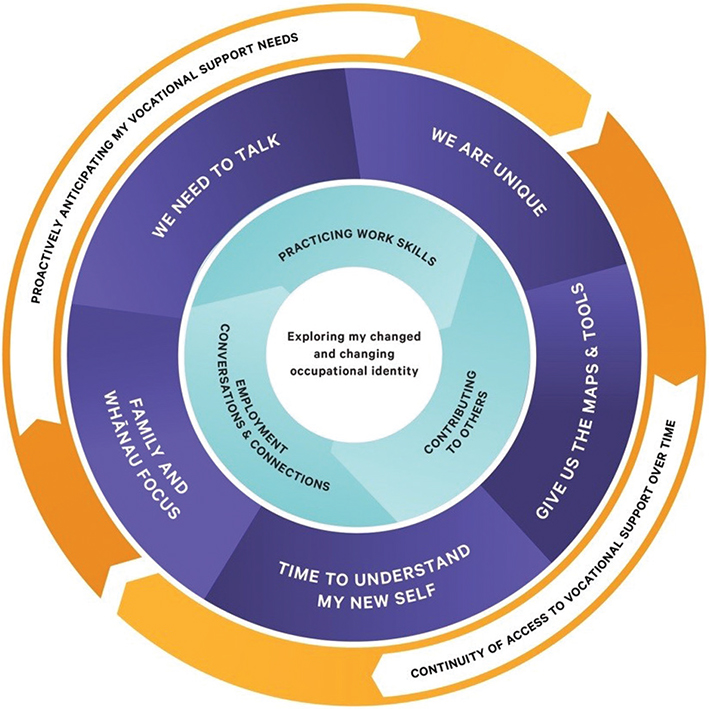

As shown in Fig. 1, the results are presented around a single overarching theme, “Exploring my changed and changing occupational identity”.

Fig. 1. Overview of analysis findings.

Within this overarching theme, Theme 1 overviews opportunities participants desired opportunities participants desired in order to explore occupational options, with sub-themes titled: (i) contributing to others, (ii) practising work skills, and (iii) employment conversations and connections.

Theme 2 overviews the key principles ensuring these opportunities were experienced in affirming ways, including: (i) family and whānau (whānau is defined as “extended family or family group; the term can also include friends who may not have any kinship ties to other members”) focus, (ii) time to understand my new self, (c) we need to talk, (d) we are unique, and (e) give us the maps and tools.

Theme 3 overviews the desired vocational service characteristics: (i) proactively anticipating my vocational support needs, and (ii) continuity of access to vocational support over time.

In the results below, extended quotes longer than 40 words evidencing the narrative are included in Table II, indicated in the text as [Quote #]. Across the findings, while some participants reflected on their experiences of provided opportunities, others alluded to opportunities they wished they had received.

Overarching theme: Exploring my changed and changing occupational identity

The range and severity of impairments experienced by participants were broad, and their RTW trajectories and experiences diverse. However, participants consistently articulated a desire for opportunities to explore their changed and changing occupational identity, often very early after stroke [Quote #1]. As detailed in the following themes, they also reflected on a need for validating environments and interactions to allow this to occur. While not all participants received these opportunities, when they did occur, early affirming opportunities to articulate and consider concerns and questions were perceived as being helpful.

Participants talked about the emerging nature of these explorations, stating that no final decisions were made at this early stage. However, early employment conversations appeared to communicate expectations and aspirations about possible future work options [Quote #2]. They also impacted a person’s confidence to explore occupational possibilities in the future as their longer-term medical and functional status became clearer. For example, in reference to early conversations, a participant talked about moving forward and stated, “I don’t think it’s a skill thing, I think maybe it’s a confidence thing” [STR15].

The 3 following themes overview, in more depth, various ways participants explored their changed and changing occupational identity, including the types of support participants desired. It should be noted that participants referenced paid and non-paid roles within the notion of occupation, with both being valued, especially when considering RTW trajectories toward paid roles.

Theme 1: Opportunities to explore work options – often at an early stage.

Theme 1 gives an overview of the opportunities participants wanted in order to explore RTW options that might work for them. The varied ways participants explored their changed and changing occupational selves are discussed in relation to: (i) opportunities to contribute to others, (ii) opportunities to test themselves and build confidence by practising work skills, and (iii) opportunities to maintain connections with their previous managers and work colleagues.

Opportunities to contribute to others. Many participants identified that engaging in activities and roles enabling their contribution to others provided low-pressure environments to self-assess their current capabilities and capacities. In addition, these experiences and spaces contributed to a sense of purpose and provided avenues to build confidence about their occupational futures. As examples, participants described their involvement in stroke support groups, caregiving for children, supporting their spouse in work, and helping with sports tournaments. One participant, who had a caregiving role with her baby granddaughter for 2 days a week, stated, “I really relished being trusted … that was really helpful, to feel useful” [STR26]. For those who felt they could not contribute a great deal, engaging with people still allowed them to feel part of things, created the spaces for normalization of experience, helped them to better understand common impacts of stroke, and provided motivation when thinking about future work roles [Quote #3].

For many participants, collective aspects of contributing to and receiving from others supported them in gaining and retaining recognition of their self-worth. For example, a regional group of Māori impacted by stroke supported each other and collectively advocated for change, preparing the road ahead for others coming [Quote #4].

However, engagement in non-paid roles did not automatically guarantee that participants would benefit. For example, a participant felt that the vocational provider’s suggestion of volunteer work being more appropriate than paid work contributed to her feeling “less valued”. Instead, she wanted to choose her non-paid contribution based on her retained skills as a consultant. Specifically, she felt she could lend her voice to issues of accessibility within community advocacy spaces, stating, “I think my value is lending my voice in terms of someone that’s got a disability perspective” [STR33].

Opportunities to practise work skills. Participants wanted curated opportunities to test themselves, check expectations and build confidence by practising work skills, even within a few weeks after their stroke. Examples included wanting to practise social conversations with people they did not know, planning and organizational tasks, and discrete physical tasks. For example, STR06 spoke about the value of building confidence in communicating with unfamiliar people by practising in café settings. This reticence in social situations was aligned with the types of situations she would also experience in a work setting [Quote #5]. The desire to test oneself was particularly evident for those participants with changes in their communication or cognition. These opportunities allowed them to assess themselves and to gain feedback about what they could still do well (capabilities) and for how long they could do it (capacity).

Participants felt that early opportunities to practise skills, not just waiting to see what spontaneous recovery might occur with time, also contributed to functional improvements and supported their RTW goals. “The more you do stuff, the more you do stuff if you know what I mean. It’s hard to type, it’s hard to do everything, but if you do it, you get better at it” [STR22]. However, even when paid work was not seen as being a longer-term option, participants referenced the value of real-world practise opportunities, since they could gain external feedback about their functioning and start re-building confidence in retained abilities, developing self-assessment skills, and developing strategies to manage any ongoing impairments and limitations.

Participants’ narratives highlighted 2 critical contexts that needed to be present for these practise opportunities to be perceived positively. Firstly, participants frequently referenced the need for a slow, staged, low-responsibility approach to practising skills, whether as part of therapeutically-curated situations, volunteer roles or paid employment roles. “I really want to work part-time to see how it goes; very small, not much responsibility” [STR28]. Some participants did get offered this type of experience, and they reported the positive benefits of being an observer. They also appreciated opportunities to contribute to the workplace from areas of retained capabilities and expertise.

Secondly, participants talked about the need for their skills and expertise to be seen and recognized, and to be given opportunities that reflected their abilities and interests. For example, a participant reflected that the vocational provider, “would help me get into work, but the jobs were not, how could I say it? You know, I had a senior [role pre-stroke], and the last thing I wanted to do is push trolleys” [STR01]. This alignment also allowed participants to explore what they felt they could offer in a future paid work role, reinforcing their sense of self-worth. For some, educational opportunities provided a context that allowed this to happen [Quote #6]. If there was a lack of opportunities or alignment with abilities and interests, then experiences could contribute to participants feeling even further devalued, experiencing an ongoing loss of confidence, and undermining occupational identity [Quote #7].

Opportunities for employment conversations and connections Participants who were offered opportunities to have conversations and maintain connections with their employers, managers and work colleagues felt that this supported them to explore what employment might look like post-stroke. This was particularly evident for those who could RTW in the short to medium term; although, those with less clarity about their RTW plans also benefited from the connections [Quote #8]. Regular, informal, and non-pressured conversations with managers and colleagues to explore future work tasks and responsibilities could be positive – particularly for participants who held work roles with a high degree of autonomy [Quote #9]. For those participants who could not RTW in the short-term, discussions around graduated and individualized pathways contributed to a sense of agency within the RTW process and allowed participants to “have something that you can work towards” [STR30]. As such, these employer conversations and connections created a hopeful space in which work was viewed as possible.

However, employer conversations and connections were not a guarantee of success. In the context of a lack of information and employer understanding, participants often described all-or-nothing options presented to them when they talked with their employers about returning to work. “It was, ‘do this job that you have, one way or another… or don’t be here’”[STR25]. Furthermore, participants frequently described this lack of employer and colleague understanding as undermining occupational identity.

Participant narratives suggested that they were more likely to perceive colleagues as acting in their best interests; that is, judging colleagues’ responses as being supportive rather than undermining, when meaningful connections with work colleagues had been maintained while the participant was not working [Quote #10]. Participants referenced colleagues providing information, adapting the work programmes to allow them to work in their areas of strength, taking care of more complex tasks, and providing practical and emotional support. Reshaping work roles, when they did occur, appeared to provide participants with increased confidence and further enhanced a positive sense of self [Quotes #11 and #12].

Theme 2: Key principles ensuring opportunities were experienced in affirming ways

Theme 2 overviews the fundamental principles participants highlighted as ensuring opportunities to explore a changed and changing occupational identity were perceived as positively supportive rather than detrimental. Participants talked about needing, both individually and collectively as family or whānau, time and space to understand their new selves, be able to speak of occupational options, be seen and treated as unique, and be able to access the maps and tools for their RTW journeys.

Family and whānau focus. While some participants talked about exploring occupational identity as a personal journey, a large number explicitly referenced the notion of occupational self in the context of family, whānau and community, in contrast to an individual focus. For example, STR03 stated that he would have liked vocational rehabilitation to “know where the patient is at, where the family are at” since he had “a strong, knowledgeable whānau, and they knew enough about me to get me to re-engage in all of the things I love” [STR03]. Participants also referenced the importance of family members receiving support and education to better understand the impacts of stroke and how best to support the individual to return to a work role aligned with and supporting their occupational identity [Quote #13].

Time to understand my new self. Most participants indicated that exploring changed and changing aspects of self-identity took time, was challenging, and frequently took place in conversations about their past, present and future occupational selves early after stroke [Quote #14]. For some participants, self-identity and biographical continuity more generally, rather than occupational identity specifically, was the focus. In these cases, participants’ experiences highlighted the importance of conversations around who they were as people and the impact this had on all areas of their lives, including their physical, relational and spiritual selves [Quote #15]. Furthermore, internalized stigma was apparent within several participants’ narratives, impacting their confidence to undertake previous work roles, sustain work team practices and develop new relationships with clients [Quote #16]. The opportunity to talk through internalized narratives within occupationally-focused conversations appeared to contribute to participants’ sense-making and allowed them to review previously held attitudes about disability.

We need to talk. Participants indicated that they and their family or whānau wanted to start talking about vocational concerns from an early stage (i.e. within a few days to weeks of their stroke). However, participants’ narratives also suggested that these employment conversations often did not occur, were discouraged, or attempts were made to delay discussions [Quote #17]. Many participants provided examples of feeling invalidated when talking with healthcare providers about their future functioning in a work role. In addition, they felt that conversations were discouraged, since staff perceived that it was too early to have these discussions given a lack of clarity about their long-term functional status [Quote #18]. However, even at an early stage, concerns related to financial implications of a change of employment status, their legal and workplace rights, and how family and whānau members could access knowledge to inform their collective decision-making were evident. Participants also referenced the value of early conversations that both normalized the experiences of recovery after a stroke and challenged unrealistic expectations around RTW trajectories.

Participants suggested that discussing occupational options amid uncertainty could be helpful, with one suggesting that “[talking to a vocational provider has] kind of taken worry away from me. It’s eased the scariness, I suppose” [STR09]. Furthermore, early opportunities to talk helped participants appreciate there was a process that could be accessed in the future once they were able to prioritize planning for and enacting specific RTW pathways [Quote #19].

For some participants, their ability to engage in the sense-making process took time. Some clearly articulated that starting employment conversations too early would not have been helpful for them, given their medical status. These participants felt they would not have been able to retain the information. However, many of these same participants could also see the possible advantages in retrospect and would have found it helpful to have access to someone to talk to when they did feel it was more appropriate for them [Quote #20]. Therefore, even for participants who stated that they would have limited ability to engage in early employment conversations, the opportunity to make connections with vocational providers, to be given an overview of possible RTW pathways and to know how to access support when needed, appeared to be of longer-term value.

We are unique. Participants wanted vocational providers to get to know them, their specific situations, and those of their family and whānau. Many participants talked about cultural knowledge or an attitude of deep listening required by vocational providers to ensure that the unique needs of participants and their families/whānau were understood. In the context of participants’ experiences, deep listening refers to non-judgemental, responsive and reflective communication that meets the person and whānau where they are at. When deep listening, accompanied by a holistic focus, occurred, participants talked about their sense of self being supported, meaning they were more able to explore their occupational identity and future RTW options in positive ways. For example, STR19 referred to what she experienced in her interactions with a vocational provider soon after her stroke [Quote #21]. The respectful, tailored, and individualized approach contributed to STR19 feeling motivated and engaged in the vocational rehabilitation process. “It made me want to work with her and made me respect her as a practitioner. And it made me value the advice she gave, I think, so I really took notice of what she was saying” [STR19]. This contrasted with the check-list approach that she experienced with other vocational rehabilitation providers, who made her feel like she “was more of a number”.

For some participants, especially those with higher level executive difficulties, their impairments were often more significant than healthcare providers appreciated or addressed. This contributed to a lack of specific support targeted to the particular work role requirements or challenges the person encountered, and contributed to poor RTW experiences and outcomes [Quote #22]. The need to understand the unique aspects of participants and their family or whānau was closely related to how information about proximal and distal RTW options and pathways were communicated. Many participants referenced a large amount of written material provided to them, but which contributed to confusion and a lack of accessible knowledge [Quote #23].

Give us the maps and the tools. Participants wanted to be actively involved in considering their options and partnering in decision-making as much as possible. They frequently talked about a desire to understand RTW pathways and processes and a range of strategies they could use to take action and advocate for themselves in the future. Enacting personal strategies, using maps and tools, allowed them to sustain momentum, reinforced a positive view of self, and supported a sense of hope [Quote #24].

Without access to these maps and tools, participants could not effectively contribute to coordinating their own RTW pathways. For several participants, being provided with knowledge about their legal rights and employer responsibilities would have supported their autonomy and ability to advocate for themselves. Others wanted to be offered pathways to exploring assistive technology solutions that may optimize their participation in work roles. A need for more information about how transportation options could be accessed was highlighted by many participants. For instance, despite work readiness being achieved, misinformation about temporary disqualification from driving and reassessment waitlist times meant that some participants could not RTW in a role requiring driving [Quote #25].

Theme 3: Vocational service characteristics

Within this theme key vocational support service characteristics related to proactivity and continuity are overviewed. Rather than reactive services, participants talked about needing RTW services that proactively anticipated and responded to their current and future needs, and which they could continue to access over time.

Proactively anticipating my vocational support needs. Participants talked about the need for proactive RTW supports. They wanted to understand typical trajectories and pathways for exploring RTW options so that they could actively contribute to choosing solutions most relevant to their unique situation. For example, a participant referred to the vocational support coming to him: “I didn’t have to go chasing it. It was presented as an option, and ‘Yes, thank you. I’ll do that’” [STR13]. However, many participants shared that they felt they were expected to tell vocational providers their questions and concerns. They described this as being unhelpful since they did not know what was reasonable to expect nor what options could be offered to them [Quote #26].

Early introduction to people who could provide navigation through vocational services and pathways as and, when required, supported participants to experience a sense of hope, along with clarity about how they might enact their vocational goals [Quotes #27 and #28]. Many participants discussed the value of having a proactive plan, explicitly articulated and showing key milestones to be achieved. However, participants also recognized the need for plans to remain responsive to their emerging needs and changed and changing occupational selves. For instance, a participant talked about her desire for a flexible plan: “Just to start having an idea what the options were, you know, like that you can do limited hours and stuff” [STR29].

Continuity of access to vocational support over time. Participants also wanted to access vocational support over time rather than being offered services that responded to issues at a single point in time and/or in a time-limited way. A desire for continuity also included coherent messaging about vocational options, expectations, and planning between rehabilitation services provided in inpatient and community settings. Without continuity, participants experienced a lack of clarity and fragmentation of support, contributing to disempowerment and a loss of hope [Quote #29].

Participants frequently talked about the non-linear aspects of exploring their occupational futures in line with the non-linear characteristics of the recovery. Given the complexity of participants’ RTW pathways, their vocational needs and aspirations changed over time, requiring them to access vocational support longitudinally. The inability to access support as and when needed and how they needed it was a strong feature of participants’ RTW narratives. Many talked about being unsure who to contact if vocationally related issues arose [Quote #30]. When participants had greater clarity over the process and knew how to access support when required, they were empowered to take action to achieve their RTW goals, and their occupational identity was supported.

DISCUSSION

By reflecting on participants’ experiences, this study developed a nuanced understanding of contexts impacting people seeking employment following stroke. The study identified the resources that best support the journey towards meaningful and sustainable employment, and how early vocational intervention could support RTW goals, and health and wellbeing outcomes. Participants’ experiences suggest that early validating opportunities to explore their changed and changing occupational identity supported the enactment of their vocational intentions. For participants in this study, the centrality of a person’s identity following stroke was intrinsically linked to their thoughts about their occupational options. Participants experienced self-identity as continuous yet fractured, echoing the Life Thread Model as conceptualized by Ellis-Hill et al. (28) articulating how coherence and predictability are challenged, and can best be supported, following a stroke.

For many people, occupation generally, and paid work roles specifically, were integral to the expression of their identity. This was particularly evident for those with cognitive or communicative changes. Therefore, from a provider perspective, ensuring opportunities to intentionally listen to how people consider their changed and changing identity appears to be important, even in the very early stages after stroke. Unfortunately, consistent with other work (29, 30), participants’ experiences suggest that listening to people’s concerns following stroke does not happen consistently, with many feeling dissuaded from asking questions and interacting with healthcare professionals about employment early after their stroke.

Participants’ opportunities for self-reflection occurred in tandem with opportunities to test themselves in a range of environments. For some, this also involved addressing internalized stigma they may hold about occupational possibilities for people with ongoing impairments after stroke. While it should be noted that these early employment conversations would need to be sensitive to, and account for, the presence of depressive symptoms post-stroke (31), it seems plausible that early conversations allowing people to explore patterns of thinking may also support wellbeing and mood.

The current study highlights the importance of unique, tailored approaches to early conversations and interventions aimed at supporting RTW following stroke. Many participants strongly endorsed including family and support networks in discussions and service delivery, particularly relevant in NZ (32, 33). Occupational identity was, for many, enacted through, and mediated within, the whole family system and support network relationships, contributing to how a person could express their occupational identity across time. Actively and intentionally including family and other support people in discussions around occupational futures seems prudent and most likely to support sustainable RTW outcomes, given evidence demonstrating the significant financial and emotional pressures experienced by families (34–36).

Early conversations about employment also needed to establish expectations for likely future challenges, since, for participants in this study, new areas of need emerged over time as they returned to employment and sought to sustain it over time; for example, setting the stage for developing dynamic, person-centred and adaptive attitudes toward working while living with the enduring consequence of stroke (37). Participants’ experiences also highlight the importance of the nature of these conversations, and a desire to receive support with trusted people who listened and respect their holistic selves.

The current study highlights the importance of people following stroke, their families and support people, being given the resources to self-direct and enact their own RTW trajectories, with many participants expressing a lack of autonomy and self-efficacy around achieving their occupational aspirations within vocational services they had accessed. Pathways and tools to enact their intentions were also of critical importance. These pathways and tools include useable knowledge about options for accessing vocational support over time, information about legal rights, and the curation of volunteer roles or graduated RTW programmes. These findings resonate with the increasing attention being given to self-management approaches within stroke rehabilitation (38) and echo the approach articulated within the Taking Charge after Stroke intervention (39), based on early listening conversations supporting autonomy, connectedness, mastery and purpose responses within people following stroke (40). Findings also endorse those of a systematic scoping review by Murray et al. (13), suggesting that vocational services need to be coordinated, interdisciplinary, and be accessible over the long term.

This paper sits within a larger EVocS study, aiming to develop early intervention vocational services for people after stroke in NZ (18, 19, 21–23). Like the SCI population (24), people who have had a stroke also endorse the value of early intervention approaches, and especially unpressured listening conversations, in supporting occupational identity. Findings from this study suggest that these early conversations can benefit a broad cohort of people following stroke. This is in contrast with service currently accessible to people following stroke in NZ who focus primarily on people who are likely to return to paid work in a similar role and with the same employer. Broadening eligibility criteria for early vocational support would allow more people to explore their retained strengths and capacities, even amid a lack of clarity about long-term functional outcomes, thereby potentially contributing to the maintenance of their occupational self and the enactment of hope. However, as indicated in previous publications within this project, the proximal outcomes of these early interventions should be explored in terms of hope and self-efficacy, with RTW rates and work sustainability being more distal outcomes (18, 19).

Participants in this paper were reflecting on the experiences of their RTW pathways, on average, 6.5 years after their stroke. More information about how people within the first few months of a stroke respond to employment conversations is required. Distinguishing early conversations focused on supporting occupational identity from other approaches that support self-management and biographical continuity (e.g. Take Charge after Stroke (39) or other self-management approaches (38)) also requires further consideration. Specifically, it is unclear if people’s responses to these early conversations differ depending on the person they are conversing with (e.g. healthcare professional vs peer). Within the broader EVocS project, we have conducted an observational study (manuscript under peer review) exploring both the EIVR responses in people following SCI as well as conceptualizing how EIVR functions during spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Findings from the observational study have suggested that unity, flexibility and clarity between EIVR services and the wider multidisciplinary team (MDT) are essential foundations for supporting people with SCI on their journey to employment. An observational study replicating this work in a range of stroke rehabilitation contexts (e.g. inpatient rehabilitation units, early supported discharge services, and other community-based rehabilitation programmes) would contribute to our understanding of team processes and early responses to vocational support in the stroke population.

CONCLUSION

Participants experiences endorse the value of early vocational interventions aimed at optimizing RTW outcomes. The curation of opportunities soon after stroke allows people to explore their changed and changing occupational identity and to both envisage pathways toward their possible occupational futures and enact their occupational intentions, both non-paid and paid. Early validating employment conversations and opportunities to practise work skills allowed people following stroke time to gradually regain confidence in their retained skills and capabilities, rather than focusing only on their difficulties and impairments, and allowing them to develop and use strategies to coordinate their own RTW trajectories. Vocational rehabilitation services need to address the holistic and long-term needs of people following stroke, their families and their support networks, including employers and work colleagues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the NZ Health Research Council in collaboration with the Ministry of Social Development (Grant 19/834). The authors would like to thank participants who gave their time and shared their experiences.

All procedures in the study were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1975.

REFERENCES

- Carter K, Anderson C, Hacket M, Feigin V, Barber PA, Broad JB, et al. Trends in ethnic disparities in stroke incidence in Auckland, New Zealand, during 1981 to 2003. Stroke 2006; 37: 56–62. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000195131.23077.85

- Feigin VL, Norrving B, Mensah GA, Fisher M, Iadecola C, Sacco R. Global Burden of Stroke. Circ Res 2017; 120: 439–448. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0

- GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019; 18: 439–458. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X

- Leng T, Xiong ZG. Treatment for ischemic stroke: from thrombolysis to thrombectomy and remaining challenges. Brain Circ 2019; 5: 8–11. doi:10.4103/bc.bc_36_18

- Ranta A. Projected stroke volumes to provide a 10-year direction for New Zealand stroke services. New Zeal Med J 2018; 22: 15–28.

- Feigin VL, Krishnamurthi RV, Barker-Collo S, McPherson KM, Barber PA, Parag V, et al. 30-year trends in stroke rates and outcome in Auckland, New Zealand (1981–2012): a multi-ethnic population-based series of studies. PLoS One 2015; 10: 1–28. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134609

- Thompson SG, Barber PA, Gommans JH, Cadilhac DA, Davis A, Fink JN, et al. Geographic disparities in stroke outcomes and service access: a prospective observational study. Neurology 2022; 99: e414–e426. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200526

- Wyeth EH, Wilson S, Nelson V, Harcombe H, Davie G, Maclennan B, et al. Participation in paid and unpaid work one year after injury and the impact of subsequent injuries for Māori: results from a longitudinal cohort study in New Zealand. Injury 2022; 53: 1927–1934. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2022.03.006

- Fadyl JK, Anstiss D, Reed K, Levack WMM. Living with a long-term health condition and seeking paid work: qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Disabil Rehabil 2022; 44: 2186–2196. doi:10.1080/09638288.2020.1826585

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. Australian and New Zealand Consensus Statement on the Health Benefits of Work. Sydney, 2011. [cited 2022 Oct 2]. Available from: www.racp.edu.au

- Sen A, Bisquera A, Wang Y, McKevitt CJ, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD, et al. Factors, trends, and long-term outcomes for stroke patients returning to work: The South London Stroke Register. Int J Stroke. 2019; 14: 696–705. doi:10.1177/1747493019832997

- Schwarz B, Claros-Salinas D, Streibelt M. Meta-synthesis of qualitative research on facilitators and barriers of return to work after stroke. J Occup Rehabil 2018; 28: 28–44. doi: 10.1007/s10926-017-9713-2

- Murray A, Watter K, McLennan V, Vogler J, Nielsen M, Jeffery S, et al. Identifying models, processes, and components of vocational rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: a systematic scoping review. Disabil Rehabil 2022; 44: 7641–7654. doi:10.1080/09638288.2021.1980622

- Waddell Gordon, Burton AKim, Kendall Nicholas. Vocational rehabilitation: what works, for whom, and when? TSO London 2008. [cited 2022 Oct 2]. Available from: http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/5575/

- Fadyl JK, McPherson KM. Understanding decisions about work after spinal cord injury. J Occup Rehabil 2010; 20: 69–80. doi:10.1007/s10926-009-9204-1

- Krause JS, Terza J v, Saunders LL, Dismuke CE. Delayed entry into employment after spinal cord injury: factors related to time to first job. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 487–491. doi:10.1038/sc.2009.157

- Middleton JW, Johnston D, Murphy G, Ramakrishnan K, Savage N, Harper R, et al. Early access to vocational rehabilitation for spinal cord injury inpatients. J Rehabil Med 2015; 47: 626–31. doi:10.2340/16501977-1980

- Dunn JA, Martin RA, Hackney JJ, Nunnerley JL, Snell DL, Bourke JA, et al. Developing A Conceptual Framework for Early Intervention Vocational Rehabilitation for People Following Spinal Cord Injury. J Occup Rehabil 2022; doi:10.1007/s10926-022-10060-9.

- Dunn JA, Hackney JJ, Martin RA, Tietjens D, Young T, Bourke JA, et al. Development of a programme theory for early intervention vocational rehabilitation: a realist literature review. J Occup Rehabil 2021; 3: 730–743. doi:10.1007/s10926-021-10000-z

- Accident Compensation Corporation. Getting back to work after an injury [cited 2022 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.acc.co.nz/im-injured/financial-support/return-to-work/

- Paul C, Derrett S, Mcallister S, Herbison P, Beaver C, Sullivan M. Socioeconomic outcomes following spinal cord injury and the role of no-fault compensation: longitudinal study. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 919–925. doi:10.1038/sc.2013.110.

- Dunn J, Martin RA, Hackney JJ, Nunnerley JL, Snell D, Bourke JA, et al. Early vocational rehabilitation for people with spinal cord injury: a research protocol using realist synthesis and interviews to understand how and why it works. BMJ Open 2021; 11: 1–8. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048753

- Snell DL, Hackney JJ, Maggo J, Martin RA, Nunnerley JL, Bourke JA, et al. Early vocational rehabilitation after spinal cord injury: a survey of service users. J Vocat Rehabil 2021; 55: 323–333. doi:10.3233/JVR-211166

- Martin RA, Nunnerley JL, Young T, Hall A, Snell DL, Hackney JJ, et al. Vocational wayfinding following spinal cord injury: in what contexts, how and why does early intervention vocational rehabilitation work? J Vocat Rehabil 2022; 56: 243–254. doi: 10.3233/JVR-221189

- Braun V, Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual Psychol 2022; 9: 3–26. doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Shaw J, Gray CS, Baker GR, Denis JL, Breton M, Gutberg J, et al. Mechanisms, contexts and points of contention: operationalizing realist-informed research for complex health interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18: 1–12. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0641-4

- Emmel N, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, Monaghan M, Dallin S. Doing realist research. London: SAGE; 2018.

- Ellis-Hill C, Payne S, Ward C. Using stroke to explore the Life Thread Model: An alternative approach to understanding rehabilitation following an acquired disability. Disabil Rehabil 2008; 30: 150–159. doi:10.1080/09638280701195462

- Carragher M, Steel G, O’Halloran R, Torabi T, Johnson H, Taylor NF, et al. Aphasia disrupts usual care: the stroke team’s perceptions of delivering healthcare to patients with aphasia. Disabil Rehabil 2021; 43: 3003–3014. doi:10.1080/09638288.2020.1722264

- Kohler M, Mayer H, Kesselring J, Saxer S. (Can) not talk about it – urinary incontinence from the point of view of stroke survivors: a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci 2017; 32: 371–379. doi:10.1111/scs.12471

- Hackett ML, Anderson CS. Frequency, management, and predictors of abnormal mood after stroke: the Auckland Regional Community Stroke (ARCOS) Study, 2002 to 2003. Stroke 2006; 37: 2123–2128. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000231387.58943.1f

- Harwood M, Ranta A, Thompson S, Ranta S, Brewer K, Gommans J, et al. Barriers to optimal stroke service care and solutions: a qualitative study engaging people with stroke and their whānau. New Zeal Med J 2022; 135: 81–93.

- Pene BJ, Aspinall C, Wilson D, Parr J, Slark J. Indigenous Māori experiences of fundamental care delivery in an acute inpatient setting: a qualitative analysis of feedback survey data. J Clin Nurs 2021; 31: 3200–3212. doi:10.1111/jocn.16158

- McAllister S, Derrett S, Audas R, Herbison P, Paul C. Do different types of financial support after illness or injury affect socio-economic outcomes? A natural experiment in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med 2013; 85: 93–102. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.041

- Cameron JI, Naglie G, Silver FL, Gignac MAM. Stroke family caregivers’ support needs change across the care continuum: a qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disabil Rehabil 2013; 35: 315–324. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.691937

- Rigby H, Gubitz G, Phillips S. A systematic review of caregiver burden following stroke. Int J Stroke 2009; 4: 285–292. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00289.x

- Karanika-Murray M, Biron C. The health-performance framework of presenteeism: towards understanding an adaptive behaviour. Hum Relat 2020; 73: 242–261. doi:10.1177/0018726719827

- Jones F, Kulnik ST. Self-Management. In: Lennon S, Verheyden G, Ramdharry G, editors. Physical management for neurological conditions e-book. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2018, p. 379–396. ISBN: 9780702077234.

- Fu V, Weatherall M, McPherson K, Taylor W, McRae A, Thomson T, et al. Taking Charge after Stroke: a randomized controlled trial of a person-centered, self-directed rehabilitation intervention. Int J Stroke 2020; 15: 954–964. doi:10.1177/1747493020915144.

- Harwood M, Weatherall M, Talemaitoga A, Barber PA, Gommans J, Taylor W, et al. Taking charge after stroke: promoting self-directed rehabilitation to improve quality of life – a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2012; 26: 493–501. doi:10.1177/0269215511426017