ORIGINAL REPORT

SEX/GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SERVICE USE PATTERNS, CLINICAL OUTCOMES AND MORTALITY RISK FOR ADULTS WITH ACQUIRED BRAIN INJURY: A RETROSPECTIVE COHORT STUDY (ABI-RESTART)

Georgina MANN, PhD1,2, Lakkhina TROEUNG, PhD1 and Angelita MARTINI, PhD1

From the 1Brightwater Research Centre, Brightwater Care Group, Inglewood and 2School of Psychological Science, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

Objective: To identify sex/gender differences in functional, psychosocial and service use patterns in community-based post-acute care for acquired brain injury.

Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Subjects/patients: Adults with acquired brain injury enrolled in post-acute neurorehabilitation and disability support in Western Australia (n = 1,011).

Methods: UK Functional Independence Measure and Functional Assessment Measure (FIM + FAM), Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory-4, goal attainment, length of stay (LOS), number of episodes of care and deaths were evaluated using routinely collected clinical and linked administrative data.

Results: At admission, women were older (p < 0.001) and displayed poorer functional independence (FIM + FAM; p < 0.05) compared with men. At discharge, there were no differences in goal attainment, psychosocial function or functional independence between men and women. Both groups demonstrated functional gains; however, women demonstrated clinically significant gains (+ 15.1, p < 0.001) and men did not (+ 13.7, p < 0.001). Women and men had equivalent LOS (p = 0.205). Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status predicted longer LOS for women but not for men. Being partnered predicted reduced LOS for women but not men. Women had a higher risk of multiple episodes of care (p < 0.001), but not death (p = 0.409), compared with that of men.

Conclusion: At admission to rehabilitation and disability support services for acquired brain injury, women have poorer functional independence and higher risk of multiple episodes of care, compared with men, suggesting greater disability in the community. By the time of discharge from these services, women and men make equivalent functional and psychosocial gains. The higher risk of multiple episodes of care for women relative to men suggest women may need additional post-discharge support, to avoid readmission.

LAY ABSTRACT

Acquired brain injury is associated with long-term consequences for health and wellbeing. Despite this, relatively little research has examined sex and gender differences in patterns of service use, functional and psychosocial outcomes, and risk of death in post-acute care for acquired brain injury. This study evaluates the admission and discharge characteristics of 1,011 adults with acquired brain injury. Findings indicate that, while women present with poorer functional independence at admission, post-acute care for acquired brain injury provides opportunities for equivalent functional and psychosocial gains for men and women. Women are at higher risk of requiring multiple episodes of care, compared with men, and women in some groups have a longer length of stay in post-acute care than men, although they are at no greater risk of death during care. This indicates that additional post-discharge support may be required for women with acquired brain injury, but that post-acute care supports both men and women to make meaningful functional improvements.

Key words: brain injuries; gender; sex; neurological rehabilitation; functional independence.

Citation: J Rehabil Med 2023; 55: jrm5303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v55.5303

Copyright: © Published by Medical Journals Sweden, on behalf of the Foundation for Rehabilitation Information. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Accepted: Jul 11, 2023; Published: Sep 12, 2023

Correspondence address: Georgina Mann, University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Hwy, Crawley, WA, 6009 Australia. E-mail: Georgina.Mann@uwa.edu.au

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is a common phenomenon, with estimates suggesting 1 in 45 Australians have an ABI that limits their abilities (1). For many, these limitations are long-term, requiring ongoing medical and social support (2) and rehabilitation (3–8). In particular, since survivors of ABI are often young (9), long-term familial and societal care is required throughout their life (2). Sex and gender are associated with differing outcomes and patterns of service use, through acute hospitalization (10–12) to community reintegration (13, 14). The term “sex” refers to physical, chromosomal, and hormonal attributes of humans, whereas “gender” refers to socially constructed roles and how an individual identifies (15). While sex and gender are treated as interchangeable constructs in some studies, other studies treat sex as a biological phenomenon and gender as a social one (10). It is difficult to separate the social and biological influence of sex and gender on health outcomes, therefore the current study examines sex and gender as a single factor, described throughout this paper as “sex/gender”.

Research examining sex/gender differences in outcomes from traumatic brain injury (TBI) has identified several differences, with men demonstrating poorer executive functioning (16), greater likelihood of hospital discharge against medical advice (10), and higher long-term mortality rates (17, 18). Women demonstrate greater risk of self-harm-related death (18), poorer economic quality of life (14), poorer functional outcomes (19), and report greater difficulty with daily functioning (20). Indeed, some research indicates that family adherence to gender roles makes recovery challenging for women. Some women with TBI report that the restrictive nature of gendered family roles creates interpersonal friction when attempting to encourage their informal care supports (typically male partners) to take over gendered care roles (21), influencing their capacity to recover. There is evidence of metabolic and hormonal differences between male and female patients following TBI (10). In addition, sex differences in survivors of non-traumatic brain injury (NTBI), such as stroke, have been reported, with women being slower to seek acute care and demonstrating greater disability (22). Some of the poorer outcomes in women can be attributed to older age, poorer health pre-stroke, or differences in hospital management (12, 23). Together, this suggests that women and men have differing profiles of needs and patterns of engagement with services following ABI.

However, there is limited research specifically examining sex/gender differences in post-acute care service use and outcomes, defined as care accessed once medical or physiological stability has been reached following hospitalization (24). Prior studies have shown that engagement in post-acute care is associated with significant improvement in both functional independence and psychosocial outcomes in Australia (4–6) and internationally (25, 26), and forms a critical component of long-term recovery after ABI (4). However, this research does not disaggregate outcomes by sex or gender, which is important to identify systematic differences to inform rehabilitation service planning and person-centred rehabilitation models (22). Research evaluating sex/gender differences in length of stay (LOS) and functional outcomes from post-acute rehabilitation for TBI in Canada did not identify sex/gender differences; however, this research did not evaluate the extent to which there were sex/gender differences in the magnitude of improvement throughout services, which may provide a more comprehensive picture of women’s path to recovery (27). In addition, while there is an established pattern of sex/gender differences in post-acute mortality following discharge from hospital and over the long term (17, 18), research has yet to evaluate mortality risks within post-acute care for ABI.

This study examines sex/gender differences in the ABI-RESTaRT (28) cohort, a retrospective cohort of n = 1,011 adults with ABI enrolled in post-acute rehabilitation and disability support in Western Australia (WA), during the period 1991–2020. The overarching aims were to examine sex/gender differences in service use patterns, post-acute outcomes at discharge, and death during post-acute care. The specific aims were to identify sex/gender differences at admission to post-acute services; and to examine the impact of sex/gender on: (i) functional and psychosocial change at discharge, (ii) goal attainment at discharge, (iii) patterns of service use, and (iv) risk of death during care.

METHODS

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the University of WA Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC; RA/4/1/9232) and the WA Department of Health HREC (RGS0000002894). Clients provided written consent for their de-identified clinical data to be used for research and service evaluation as part of the conditions of entry into the community-based post-acute rehabilitation and disability service.

Study design and cohort definition

ABI-RESTaRT is a retrospective whole-population cohort comprising all clients of Brightwater Care Group’s post-acute community-based brain injury programmes and services (excluding respite) in the period 1991–2020 (28). The cohort consists of n = 1,011 adults between the ages of 18 and 65 with acquired (non-congenital) brain injury accessing services at a single provider in Western Australia. Full description of the cohort, setting, available services and relevant exclusion criteria can be seen in Mann et al.(28).

Setting

Cohort members were enrolled in any of the following 5 brain injury programmes:

- Transitional Rehabilitation Program (TRP): a neurorehabilitation programme delivered through the 43-bed purpose-built, community-based residential Oats Street rehabilitation centre in Perth, Western Australia. This program provides multidisciplinary person-centred, evidence-based neurorehabilitation for individuals with diverse ABI, with a focus on community re-integration (28).

- Transitional Accommodation Program (TAP): a step-down from hospital service with clients receiving transitional care and accommodation while supported to seek longer-term care.

- Supported Independent Living (SIL): long-term supported accommodation for individuals who require additional support with activities of daily living (ADL).

- Home and Community Care Social Skills (HACCSS): supports individuals with social engagement and activities and in-home community support.

- Capacity Building (CAPB): replaced HACCSS, offers home-based support including neurorehabilitation, support coordination, equipment, and behavioural support.

Data sources

Demographic and clinical data were extracted from electronic medical records (EMRs) recorded by staff at the community sites, and linked Hospital Morbidity and Emergency Department Data Collection and Mortality Register records from the WA Data Linkage System (29).

Key measures

Sex and gender. Sex and gender data were extracted from EMRs and hospital records. As sex and gender were not separately recorded in these sources, they are treated as a single combined variable: termed “sex/gender” in this paper. Where sex and/or gender was recorded across multiple sources, the sex and gender were consistent for all cohort members.

Demographic and clinical variables

Variables extracted from EMRs were age, sex/gender, partner status, ABI diagnosis, injury date, injury cause, hospitalization dates, prior ABI and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status. Linked hospital and emergency department records were used to validate ABI diagnosis and injury date. Geographical remoteness was calculated using the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Remoteness Area Score (30). The Index of Socio-Economic Disadvantage (IRSD) score (31) was used to determine socioeconomic disadvantage. Both of these scores were calculated based on pre-admission residential postcodes. ASGS score was modified to a dichotomous variable indicating 1 (lives in metropolitan area) or 2 (lives outside metropolitan area). IRSD was modified to a dichotomous variable, coded as 1 (Most and More Disadvantaged; IRSD quintiles 1 and 2) and 2 (Average to Least Disadvantaged; IRSD quintiles 3–5).

Service use. Length of stay (LOS) in post-acute care was calculated for those discharged from services (n = 839). An episode of care was defined as a continuous period of care within the same programme, with clients categorized as having multiple episodes of care if they transferred to a different programme after discharge from the initial care episode.

UK Functional Independence Measure and Functional Assessment Measure. FIM + FAM (32) is a 30-item measure of functional disability. FIM + FAM measures functioning across Motor (16 items; e.g. self-care, transfers) and Cognitive domains (14 items; e.g. communication, memory) on a 7-point scale from 1 (total assistance) to 7 (complete independence). The FIM + FAM has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, both for the full scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.98) and for the Motor (Cronbach’s α = 0.97) and Cognitive (Cronbach’s α = 0.96) domains, as well as a robust factor structure, making it a suitable measure of functional independence in a population with ABI (33). The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for FIM + FAM indicates the smallest difference in outcome scores that translates to clinically meaningful change (33), with a MCID of 8.0 (Motor), 7.0 (Cognitive), and 15.0 (Total). FIM + FAM was introduced in 2011; thus, those enrolled during the period 2011–2020 with complete data were included (n = 383).

Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory-4. MPAI-4 (34) is a 29-item measure assessing psychosocial disability across 3 domains: Abilities (12-items, e.g. mobility, problem-solving), Adjustment (12-items, e.g. anxiety, agitation), and Participation (8-items, e.g. initiation, social contact). It is measured from 0 (no limitation) to 4 (severe limitation). Raw scores are calculated, then converted to standardized transformed scores (T-scores) (35). Higher T-scores indicate greater impairment. MPAI-4 has satisfactory internal consistency for the full scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) and the 3 subscales (Cronbach’s α = 0.76–0.83), making it appropriate for use in this sample. The MCID is 5T-score points for MPAI-4 total (35). The MPAI-4 was introduced in 2011, therefore clients enrolled during the period 2011–2020 with complete data were included (n = 310).

Goal Attainment Scale. GAS (36) is a 5-item tool used to set and evaluate rehabilitation goals. Each client works with their healthcare team to set 3–5 individualized goals reflecting desired outcomes. At discharge, goal achievement is evaluated on a 5-point scale from –2 (a lot less than expected) to + 2 (a lot more than expected), with 0 representing achievement at the expected level. Scores are transformed into aggregated T-scores to reflect overall goal attainment, with T-score ≥ 50 indicating goals were met at the expected level or higher. GAS scores were then scored dichotomously, with T-scores ≥ 50 scored as goals attained and scores < 50 indicating goals were not attained. Goals were categorized into 9 domains defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Activity and Participation codes (37). Prior systematic review of the GAS has indicated that it is reliable, valid and appropriate for use as an outcome measure (38).

Death during care. Finally, death during post-acute care was examined for individuals discharged by 31 December 2020 (n = 823). Deaths were ascertained from the WA Mortality Register (1991–2017), with date of death used to determine whether the death had occurred during service provision.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Stata 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, Texas). Analyses were tested against alpha < 0.05 (uncorrected, 2-tailed). Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range) or count (percentage). Independent and paired-samples t-tests, and χ2 were used to compare differences in continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Multilevel modelling was used to examine change in functional and psychosocial outcomes between admission and discharge, predictors of LOS, multiple episodes of care and goal attainment. Multilevel modelling was used to control for potential bias due to service changes over time, and random individual variation.

Change in FIM + FAM and MPAI-4. Sex/gender differences in FIM + FAM (Total, Motor, Cognitive) and MPAI-4 (Total, Abilities, Adjustment, Participation) change from admission to discharge was analysed using 3-level multilevel mixed-effects regressions fit by maximum likelihood with robust standard errors. Predictors were: (i) time (admission vs discharge), (ii) sex/gender (male vs female), (iii) time*sex/gender interaction. Analyses were adjusted for 12 covariates: Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, partner status, IRSD, ASGS, age at admission, ABI diagnosis, admission programme, time since injury, prior ABI, acute LOS, injury location, and cause (internal vs external). Marginal effects were calculated to examine gender differences from admission to discharge. A priori power analysis indicated that the sample size required to detect an anticipated medium effect (f = 0.25) at a power of 0.8 with 14 predictors and a design effect of 1.80 was n = 88.

Goal attainment. Sex/gender differences in goal attainment were evaluated by examining GAS scores using 2-level multilevel logistic regression. Predictors included covariates described above. To examine sex/gender differences in attainment across the ICF Activity and Participation domains χ2 tests were used.

Service use patterns. Sex/gender differences in service use patterns were evaluated by examining LOS in post-acute care in months, and the number of episodes of care required. Episodes of care were dichotomously scored as 0 (single care episode) and 1 (multiple care episodes). Differences in LOS were analysed using a 2-level multilevel mixed-effects regression and episodes of care were analysed using a 2-level multilevel logistic regression, both examining the interaction between sex/gender and the covariates specified above. The results are expressed in odds ratios (OR), indicating how much higher the odds of an outcome are among 1 group relative to another, or adjusted probabilities, indicating the likelihood of a certain outcome.

Deaths during post-acute care. Standardized mortality ratios (SMR) were calculated using Australian reference data (41) based on client age, sex and risk-exposure time. Risk-exposure time was measured in person-years at risk, calculated from date of index admission to final discharge. The expected number of deaths was calculated by multiplying person-years at risk for each individual by age-, sex- and year-specific corresponding mortality rate in the Australian population from 1991 to 2020, then summing the result. An SMR > 1.0 indicates an increased mortality rate relative to the reference population. SMRs were considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) did not include 1.0. SMRs were not calculated for groups with fewer than 5 observed deaths, due to inaccuracy of prediction (17). Incidence rates were calculated as the proportion of deaths by 1000 person-years at risk. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) were calculated to compare the incidence rates for men and women overall, by discharge programme, age and diagnosis.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and clinical differences

Table I presents sociodemographic and clinical details of the cohort at admission. Detailed baseline characteristics and comparisons are published elsewhere (28). There were significantly more men (n = 682, 67.5%) than women (n = 329, 32.5%); p < 0.001. Women were significantly older at injury than men; p < 0.001. There were no significant differences between time from injury to admission. A significantly lower proportion of women presented to services with TBI relative to men, and women were more likely than men to present with other NTBI; p < 0.001. A greater number of men than women had an external cause of injury; p < 0.001. Women had significantly shorter acute hospitalizations than men; p = 0.017.

| Total n = 1,011 | Female n = 329 | Male n = 682 | |

| ABI diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Traumatic brain injury | 353 (34.9) | 70 (21.3)** | 283 (41.1) |

| Non-traumatic brain injury – Stroke | 292 (28.9) | 95 (28.9) | 197 (28.9) |

| Non-traumatic brain injury – Other | 263 (26.0) | 121 (36.8)** | 142 (20.8) |

| Neurological | 103 (10.2) | 43 (13.1) | 60 (8.8) |

| Programme, n (%) | |||

| Transitional Rehabilitation Program | 546 (54.0) | 160 (48.6) | 386 (56.6) |

| Transitional Accommodation Program | 121 (12.0) | 41 (12.5) | 80 (11.7) |

| Supported Independent Living | 167 (16.5) | 59 (17.9) | 108 (15.8) |

| Home and Community Care Social Skills | 70 (6.9) | 25 (7.6) | 45 (6.6) |

| Capacity Building; ACCSS: Home and Community Care Social Skills | 107 (10.6) | 44 (13.4) | 63 (7.2) |

| Age at admission, M (SD) | 45.4 (15.5) | 47.9 (17.1)** | 44.1 (14.6) |

| Age at injury, M (SD) | 42.3 (16.5) | 44.6 (18.2)* | 41.3 (15.5) |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, n (%) | 34 (3.4) | 10 (3.1) | 24 (3.6) |

| Resides in metropolitan area, n (%) | 814 (84.3) | 283 (88.4)* | 531 (82.2) |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage (IRSD Score Q1 or Q2), n (%) | 224 (22.2) | 63 (19.2) | 161 (23.6) |

| Partnered, n (%) | 291 (30.4) | 105 (34.0) | 186 (28.7) |

| Time since injury, median (IQR) months | 10.5 (5.7, 27.1) | 9.3 (5.5, 31.1) | 10.9 (5.7, 25.5) |

| Time since injury, n (%) | |||

| Early: < 1 year | 466 (49.7) | 156 (52.4) | 310 (48.4) |

| Middle: 1–2 years | 161 (17.2) | 40 (13.4) | 121 (18.9) |

| Late: > 2 years | 311 (33.2) | 102 (34.2) | 209 (32.7) |

| Injury location, n (%) | |||

| Bilateral | 752 (74.4) | 245 (74.5) | 507 (74.3) |

| Left hemisphere | 145 (14.3) | 43 (13.1) | 102 (15.0) |

| Right hemisphere | 114 (11.3) | 41 (12.5) | 73 (10.7) |

| External cause of injury, n (%) | 593 (58.7) | 165 (50.2)** | 428 (62.8) |

| Previous ABI, n (%) | 76 (7.5) | 24 (7.3) | 52 (7.6) |

| Acute hospital admission length of stay, median (IQR) months | 5.0 (2.8, 7.9) | 4.6 (2.8, 7.3)* | 5.1 (2.8, 8.25) |

| Post-acute care length of stay, mean (SD) | 26.5 (37.3) | 24.8 (30.6) | 27.4 (40.1) |

| Multiple episodes of care, n (%) | 279 (27.6) | 84 (25.5) | 195 (28.6) |

| Admission UK FIM+FAM, n | 383 | 126 | 257 |

| Motor, mean (SD) | 68.0 (32.8) | 62.2 (32.7)* | 70.8 (32.6) |

| Cognition, mean (SD) | 53.1 (20.5) | 50.4 (21.9) | 54.4 (19.8) |

| Total, mean (SD) | 121.1 (48.8) | 112.6 (50.9)* | 125.2 (47.3) |

| Admission MPAI-4, n | 310 | 104 | 206 |

| Abilities, mean (SD) | 54.5 (12.5) | 55.4 (10.5) | 54.0 (13.4) |

| Adjustment, mean (SD) | 52.0 (9.0) | 53.1 (8.9) | 51.4 (9.1) |

| Participation, mean (SD) | 43.6 (3.6) | 43.9 (3.4) | 43.5 (3.6) |

| Total, mean (SD) | 49.3 (8.3) | 50.6 (7.6) | 48.6 (8.6) |

| Goal Setting by ICF domain, n (%) | 363 | 118 | 244 |

| 1. Learning and applying knowledge | 45 (12.4) | 14 (11.9) | 31 (12.7) |

| 2. Community, social and civic life | 142 (39.2) | 48 (40.7) | 94 (38.5) |

| 3. Mobility | 83 (22.9) | 33 (28.0) | 50 (20.5) |

| 4. General tasks and demands | 157 (43.4) | 59 (50.0) | 98 (40.2) |

| 5. Domestic life | 170 (47.0) | 61 (51.7) | 109 (44.7) |

| 6. Self-care | 94 (26.0) | 28 (23.7) | 66 (27.1) |

| 7. Interpersonal interactions and relationships | 36 (9.9) | 14 (11.9) | 22 (9.0) |

| 8. Major life areas | 75 (20.7) | 20 (17.0) | 55 (22.5) |

| 9. Communication | 238 (65.8) | 78 (66.1) | 160 (65.6) |

| Goal Attainment by ICF domain, n (%) | 189 (52.2) | 61 (51.7) | 128 (52.5) |

| 1. Learning and applying knowledge | 35 (77.8) | 13 (92.9) | 22 (71.0) |

| 2. Community, social and civic life | 116 (81.7) | 41 (85.2) | 75 (79.8) |

| 3. Mobility | 55 (66.3) | 19 (57.6) | 36 (72.0) |

| 4. General tasks and demands | 115 (73.3) | 45 (76.3) | 70 (71.4) |

| 5. Domestic life | 129 (75.9) | 47 (77.1) | 82 (75.2) |

| 6. Self-care | 72 (76.6) | 21 (75.0) | 51 (77.3) |

| 7. Interpersonal interactions and relationships | 25 (69.4) | 10 (71.4) | 15 (68.2) |

| 8. Major life areas | 51 (68.0) | 15 (75.0) | 36 (65.5) |

| 9. Communication | 188 (79.0) | 62 (79.5) | 126 (78.8) |

| *Significant to p < 0.05; **Significant to p < 0.001. | |||

| FIM+FAM: UK Functional Independence Measure and Functional Assessment Measure; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; ABI: acquired brain injury; IRSD: Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage. | |||

Outcome measures at admission

Table I presents admission FIM + FAM and MPAI-4 scores. Women demonstrated significantly lower unadjusted total FIM + FAM scores than men (p = 0.018), with both groups requiring moderate assistance. Women also demonstrated significantly lower Motor functioning than men; p = 0.016. There were no significant differences in Cognitive functioning at admission.

Women and men demonstrated comparable psychosocial function, with no significant differences in unadjusted MPAI-4 total or in individual domains. Both women and men demonstrated moderate-to-severe psychosocial limitations in Abilities and Adjustment, and mild-to-moderate limitations overall and in Participation.

Functional independence at discharge

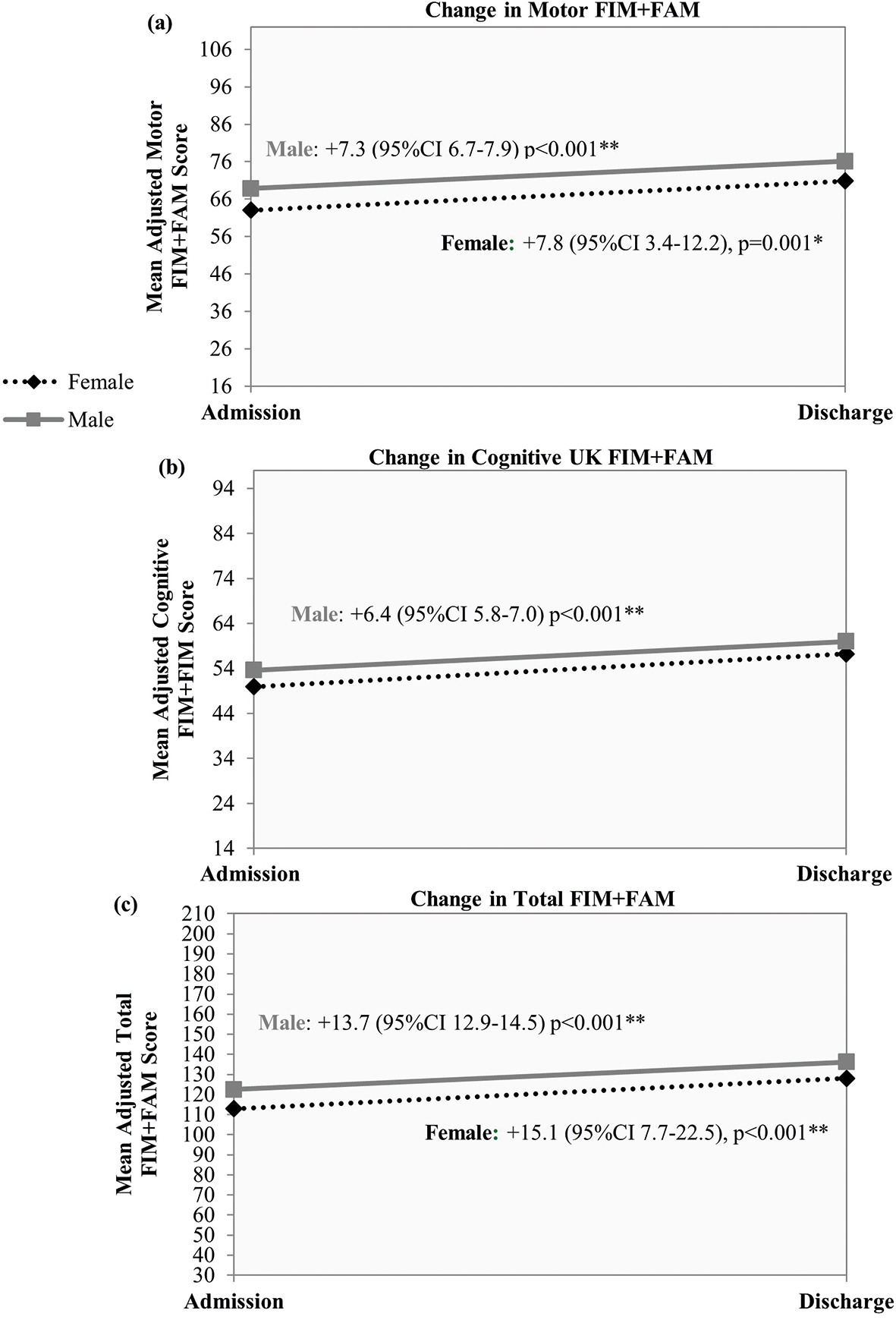

Women had undergone clinically and statistically significant functional change by discharge, with a mean adjusted gain of +15.1 (p < 0.001) in total FIM+FAM (Fig. 1). Significant Motor (p = 0.001) and Cognitive (p < 0.001) gains were also made, although the Motor domain was not clinically significant. Men made significant Total (p < 0.001), Motor (p < 0.001) and Cognitive (p < 0.001) gains at discharge, although they did not reach clinical significance.

Fig. 1. Gender differences in change in functional independence and assessment measure (UK Functional Independence Measure and Functional Assessment Measure; FIM+FAM) at discharge from post-acute care, 2011–2020, n = 326. Gender differences in mean adjusted change in (a) Motor FIM+FAM Score; (b) Cognitive FIM+FAM Score; (c) Total FIM+FAM Score. Mean scores adjusted for age, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, marital status, non-regional or remote, Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD), acquired brain injury (ABI) diagnosis, programme, time since injury, prior ABI, injury location, cause of injury, and total hospital length of stay (LOS). **Significant to p < 0.001.

At discharge, women and men did not significantly differ in magnitude of functional improvement for Total (+ 1.4, p = 0.736), Motor (+ 0.45, p = 0.858) or Cognitive (+ 0.96, p = 0.569) domains, although women had clinically significant gains and men did not.

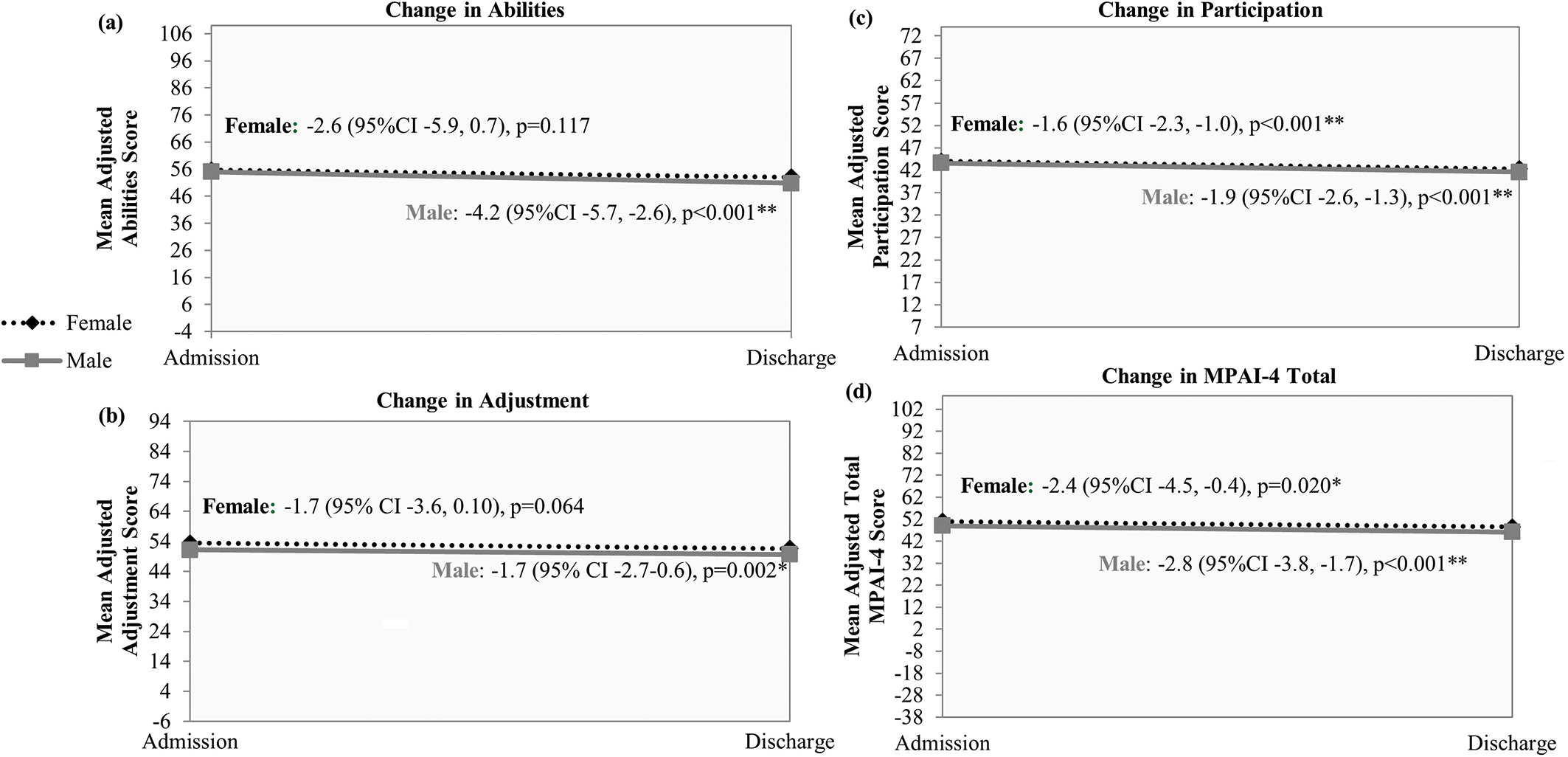

Psychosocial function at discharge

On average, women had made small, but statistically significant, improvements in psychosocial function by discharge, with a mean reduction of –2.4T in MPAI-4 total (p = 0.020) (Fig. 2). According to domains, women did not show a significant improvement in Abilities (p = 0.117) or Adjustment (p = 0.064), but did significantly improve in Participation (p < 0.001). Men demonstrated significant improvements in MPAI-4 total (p < 0.001) and all 3 domains: Abilities (p < 0.001), Adjustment (p = 0.002) and Participation (p < 0.001). However, these improvements did not reach clinical significance on any domain for either women or men.

Fig. 2. Gender differences in change in Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory-4 (MPAI-4) at Discharge from Post-Acute Care, 2011–2020, n = 310. Gender differences in mean adjusted change in (a) MPAI-4 Abilities Score; (b) MPAI-4 Adjustment Score; (c) MPAI-4 Participation Score; (d) MPAI-4 Total Score. Mean scores adjusted for age, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, marital status, non-regional or remote, Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD), acquired brain injury (ABI) diagnosis, programme, time since injury, prior ABI, injury location, cause of injury, and total hospital length of stay (LOS). *Significant to p < 0.05; **Significant to p < 0.001.

Men and women did not differ in the magnitude of their psychosocial improvement for MPAI-4 total (+ 0.31T, p = 0.770), Abilities (+ 1.55T, p = 0.297) or Adjustment (–0.09T, p = 0.939). However, men demonstrated significantly greater improvements in Participation than women (+ 0.29T, p < 0.001).

Goal attainment at discharge

There were no significant differences in ICF category goals set by men or women (Table I), with Communication goals being the most common at admission. Just over half the cohort (52.2%, n = 189) achieved their goals at the expected level or higher. Women and men achieved their goals at equivalent levels; p = 0.891. Multilevel logistic regression analysis indicated that women and men did not significantly differ in their level of goal attainment at discharge, OR = 0.93 (95% CI 0.7, 1.2); p = 0.576. There were also no significant differences in goal attainment across ICF categories for men and women.

Service use patterns at discharge

The mean unadjusted LOS in post-acute services was 26.5 months (Table I). The median number of episodes of care was 1 (IQR 1, 2). Of those in the cohort, 27.6% required multiple episodes of care. Eighty-four were women (25.5% of all women) and 195 were men (28.6% of all men).

Predictors of length of stay by sex/gender

Table II shows predictors of LOS by sex/gender. There were no significant differences in LOS between women and men in the model. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women had a significantly longer LOS than Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander men; p < 0.001. Partnered women had a significantly shorter LOS than partnered men; p < 0.001. There was no sex/gender difference in LOS between non-partnered clients; p = 0.556. Women who lived in the Metropolitan area demonstrated significantly shorter LOS than men in the Metropolitan area; (p = 0.003), although there was no difference between men and women living in regional or remote areas; p = 0.794.

| Predictors | Marginal means | Marginal effecta | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Female | Male | |||||

| Gender | 26.2 | 30.5 | –4.4 | –11.2, 2.4 | 0.205 | |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | Yes | 59.1 | 27.1 | +32.0 | 21.2,42.9 | < 0.001** |

| No/Unknown | 30.6 | 25.3 | –5.4 | –12.2, 1.4 | 0.121 | |

| Partner Status | Partnered | 24.3 | 31.8 | –7.5 | –9.0, –6.0 | < 0.001** |

| Non-partnered | 27.0 | 30.0 | –3.0 | –13.1, 7.0 | 0.556 | |

| Remoteness | Metro | 26.3 | 31.0 | –4.7 | –7.8, –1.6 | 0.003* |

| Regional or remote | 25.4 | 28.5 | –3.1 | –26.6, 20.4 | 0.794 | |

| Disadvantage (IRSD) | Q3–Q5 | 27.0 | 31.7 | –4.7 | –15.1,5.7 | 0.375 |

| Q1 & Q2 (Disadvantaged) | 23.7 | 27.1 | –3.4 | –11.1,4.3 | 0.382 | |

| ABI diagnosis | TBI | 23.3 | 26.2 | –2.8 | –8.0,2.4 | 0.286 |

| Stroke | 30.2 | 29.8 | 0.4 | –6.6,7.4 | 0.914 | |

| Other NTBI | 26.3 | 38.2 | –11.8 | –31.5, 7.9 | 0.240 | |

| Neurological | 20.3 | 25.1 | –4.8 | –43.0,33.5 | 0.807 | |

| Programme | TRP | 20.7 | 21.3 | –0.64 | –6.8,5.5 | 0.837 |

| SIL | 44.1 | 68.9 | –24.8 | –46.0, –3.6 | 0.022* | |

| CAPB | 41.2 | 54.8 | –13.5 | –25.6, –1.4 | 0.028* | |

| TAP | 22.8 | 23.8 | –1.1 | –13.5, 11.3 | 0.863 | |

| HACCSS | 39.4 | 29.5 | +9.9 | –2.8,22.5 | 0.126 | |

| Time since injury | < 1 year | 29.3 | 36.2 | –6.9 | –15.6, 1.8 | 0.118 |

| 1–2 years | 22.6 | 26.0 | –3.5 | –14.6, 7.6 | 0.540 | |

| > 2 years | 21.1 | 19.6 | +1.5 | –4.8, 7.7 | 0.650 | |

| Prior ABI | Yes | 28.5 | 42.5 | –14.0 | –35.3,7.3 | 0.199 |

| No | 26.0 | 29.5 | –3.6 | –9.3,2.2 | 0.220 | |

| Injury location | Bilateral | 25.4 | 30.3 | –4.9 | –10.2, 0.4 | 0.070 |

| Left | 27.6 | 37.2 | –9.6 | –24.6, 5.4 | 0.211 | |

| Right | 29.4 | 22.6 | –6.8 | –13.3, 26.9 | 0.507 | |

| Cause of injury | External | 27.4 | 34.2 | –6.9 | –18.3, 4.5 | 0.236 |

| Internal/Unknown | 23.8 | 23.1 | 0.7 | –3.1, 4.4 | 0.732 | |

| Episodes of care | Single | 20.8 | 22.3 | –1.5 | –5.0, 2.1 | 0.428 |

| Multiple | 38.3 | 49.3 | –11.1 | –26.9, 4.8 | 0.172 | |

| aDifference in mean length of stay (months) holding all covariates constant. | ||||||

| Adjusted for age at admission, length of acute hospitalization. | ||||||

| *Significant to p < 0.05; **Significant to p < 0.001. Significant values are bolded. | ||||||

| IRSD: Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage; ABI: acquired brain injury; TBI: traumatic brain injury; NTBI: non-traumatic brain injury; TRP: Transitional Rehabilitation Program; SIL: Supported Independent Living; CAPB: Capacity Building; TAP: Transitional Accommodation Program; HACCSS: Home and Community Care Social Skills. | ||||||

Admission programme was also a significant predictor of LOS. Men and women enrolled in the TRP (p = 0.837), TAP (p = 0.863), or HACCSS (p = 0.126) did not differ in their LOS. However, women had significantly shorter LOS than men in the CAPB (p = 0.028) and SIL programmes; p = 0.022.

Predictors of episodes of care by sex/gender

Predictors of episodes of care by sex/gender are shown in Table III. Women had 15% higher probability than men of having multiple episodes of care; p < 0.001. There were a number of groups driving this effect. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women had 59% higher probability of having multiple episodes of care than Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander men (p = 0.022), though women who were not Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander also had a higher probability of having multiple episodes of care (14%, p < 0.001). Women regardless of partner status had a higher probability of multiple episodes of care than men. Women living in the metropolitan area had a 15% higher probability of having multiple episodes of care (p < 0.001), as did those from more disadvantaged backgrounds (p < 0.001).

| Adjusted probability | Marginal effecta | 95% CI | p-value | |||

| Female | Male | |||||

| Gender | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.1, 0.2 | < 0.001** | |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | Yes | 0.76 | 0.17 | 0.59 | 0.1, 1.1 | 0.022* |

| No/Unknown | 0.40 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.1, 0.2 | < 0.001** | |

| Partner status | Partnered | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.02,0.5 | 0.032* |

| Non-partnered | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.1,0.2 | < 0.001** | |

| Remoteness | Metro | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.1,0.2 | < 0.001** |

| Regional or remote | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.14 | -0.1, 0.3 | 0.165 | |

| Disadvantage (IRSD) | Q3–Q5 | 0.30 | 0.37 | -0.08 | -0.2, 0.01 | 0.083 |

| Q1 & Q2 (Disadvantaged) | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.1,0.2 | < 0.001** | |

| ABI diagnosis | TBI | 0.48 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.1, 0.3 | < 0.001** |

| Stroke | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.13 | -0.03, 0.3 | 0.105 | |

| Other NTBI | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.12 | -0.03,0.27 | 0.103 | |

| Neurological | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.02 | -0.6, 0.6 | 0.960 | |

| Programme | TRP | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.1, 0.2 | < 0.001** |

| SIL | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.11 | -0.1, 0.3 | 0.215 | |

| CAPB | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.03 | -0.1, 0.2 | 0.710 | |

| TAP | 0.61 | 0.26 | 0.34 | -0.1, 0.8 | 0.136 | |

| HACCSS | 0.20 | 0.34 | -0.14 | -0.4, 0.1 | 0.240 | |

| Time since injury | < 1 year | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.04, 0.2 | 0.004* |

| 1-2 years | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.09 | -0.1, 0.3 | 0.313 | |

| > 2 years | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.1,0.4 | < 0.001** | |

| Prior ABI | Yes | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.25 | -0.1, 0.6 | 0.180 |

| No | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.1, 0.2 | < 0.001** | |

| Injury location | Bilateral | 0.36 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.003, 0.3 | 0.045* |

| Left | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.16 | -0.03, 0.3 | 0.098 | |

| Right | 0.61 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.2, 0.5 | < 0.001** | |

| Cause of injury | External | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.1, 0.2 | < 0.001** |

| Internal/unknown | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.15 | -0.1, 0.4 | 0.168 | |

| aDifference in marginal means, holding all covariates constant. | ||||||

| Adjusted for age at admission, total hospital inpatient length of stay. | ||||||

| *Significant to p < 0.05; **Significant to p < 0.001. Significant values are bolded. | ||||||

| IRSD: Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage; ABI: acquired brain injury; TBI: traumatic brain injury; NTBI: non-traumatic brain injury; TRP: Transitional Rehabilitation Program; SIL: Supported Independent Living; CAPB: Capacity Building; TAP: Transitional Accommodation Program; HACCSS: Home and Community Care Social Skills; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. | ||||||

Women with TBI had 21% higher probability of multiple episodes of care than men with TBI (p < 0.001), a 16% higher probability of having multiple episodes of care when admitted to TRP (p < 0.001) and a 13% and 23% higher probability of having multiple episodes of care when admitted < 1 year (p = 0.004) or > 2 years post-injury (p < 0.001), respectively. Women also had significantly higher probability than men of having multiple episodes of care when they had no prior ABI, an external cause of injury, or right or bilateral injuries.

Deaths during post-acute care

Overall, 81 deaths were recorded during post-acute care, representing a crude survival rate of 90.2%. Mortality was 5.0 times (95% CI 3.9, 6.1) higher in the cohort than in the reference population (Table IV). The median time to death from date of admission was 2.5 years (95% CI 0.9, 7.5) and the median time from injury to death was 6.4 years (95% CI 2.7, 11.1). Men had a significantly elevated mortality compared with the reference population, and compared with women. However, there was no significant difference in incidence of death between women (43/1000 py) and men (35/1000 py; p = 0.409; Table IV).

| Female | Male | IRR (95% CI) | p-value | |||||||

| Total n | Observed, expected deaths | Crude mortality rate per 1000 PY (95% CI) | SMR (95% CI)a | Total n | Observed, expected deaths | Crude mortality rate per 1,000 PY (95% CI) | SMR (95% CI)a | |||

| Total | 269 | 29, 7.3 | 42.5 (29.6, 61.2) | 4.0 (2.5, 5.4) | 554 | 52, 8.8 | 35.1 (26.8, 46.1) | 5.9 (4.3, 7.5) | 1.21 (0.7, 1.9) | 0.409 |

| Discharge programme | ||||||||||

| TRP | 138 | 3, 0.5 | 9.9 (3.2, 30.7) | – | 326 | 7, 1.9 | 10.5 (5.0, 21.9) | 3.6 (0.9, 6.3) | 0.95 (0.16, 4.14) | 0.309 |

| SIL | 63 | 22, 6.4 | 89.8 (59.1, 136.3) | 3.5 (2.0, 4.9) | 110 | 34, 6.0 | 62.3 (44.5, 87.2) | 5.7 (3.8, 7.6) | 1.44 (0.80, 2.53) | |

| CAPB | 22 | 3, 0.1 | 78.8 (25.4, 244.3) | – | 37 | 4, 0.4 | 41.2 (15.5, 109.9) | – | 1.91 (0.3, 11.3) | |

| TAP | 21 | 1, 0.1 | 21.1 (3.0, 149.7) | – | 41 | 6, 0.2 | 102.7 (46.1, 228.6) | 32.9 (6.6, 59.2) | 0.21 (0.004, 1.7) | |

| HACCSSb | 25 | 0, 0.2 | – | – | 40 | 1,0.3 | 9.0 (1.3, 63.9) | – | – | – |

| Age at discharge, years | ||||||||||

| 15–39 | 76 | 3, 0.1 | 17.0 (5.5, 52.6) | – | 192 | 7, 0.5 | 16.6 (7.9, 34.8) | 15.6 (4.0, 27.1) | 1.02 (0.2, 4.5) | 0.672 |

| 40–59 | 127 | 13, 0.6 | 40.4 (23.5, 69.6) | 20.3 (9.3, 31.3) | 274 | 30, 2.9 | 37.0 (25.9, 52.9) | 10.2 (6.6, 13.9) | 1.09 (0.5, 2.2) | |

| 60–79 | 42 | 3, 1.3 | 21.7 (7.0, 67.1) | – | 78 | 11, 3.0 | 48.1 (26.7, 86.9) | 3.6 (1.5, 5.8) | 0.45 (0.1, 1.7) | |

| 80+ | 24 | 10, 5.3 | 221.4 (119.1, 411.5) | 1.9 (0.7, 3.1) | 10 | 4, 2.4 | 212.4 (79.7, 565.9) | - | 1.04 (0.3, 4.6) | |

| ABI type | ||||||||||

| TBI | 64 | 7, 1.0 | 37.5 (17.9, 78.7) | 7.0 (1.8, 12.1) | 237 | 14, 2.1 | 20.4 (12.1, 34.4) | 6.7 (3.2, 10.2) | 1.84 (0.6, 4.9) | 0.387 |

| NTBI – Stroke | 72 | 7, 2.8 | 36.3 (17.3, 76.1) | 2.5 (0.7, 4.4) | 146 | 13, 3.8 | 45.2 (26.3, 77.9) | 3.5 (1.6, 5.4) | 0.80 (0.3, 2.2) | |

| NTBI – Other | 96 | 9, 2.3 | 42.1 (21.9, 80.9) | 3.9 (1.4, 6.4) | 122 | 15, 1.8 | 35.9 (21.7, 59.6) | 8.4 (4.1, 12.6) | 1.17 (0.5, 2.9) | |

| Neurological | 37 | 6, 1.2 | 67.9 (30.5, 151.1) | 5.0 (1.0, 8.9) | 49 | 10, 1.2 | 112.5 (60.5, 209.0) | 8.5 (3.3, 13.8) | 0.60 (0.2, 1.8) | |

| aSMR (95% CI) not calculated for groups with fewer than 5 observed deaths because of the inaccuracy of prediction. bHome and community care social skills (HACCSS) not included in the IRR calculation due to the absence of female cases. | ||||||||||

| TBI: traumatic brain injury; NTBI: non-traumatic brain injury; TRP: Transitional Rehabilitation Program; SIL: Supported Independent Living; CAPB: Capacity Building; TAP: Transitional Accommodation Program; ABI: acquired brain injury. | ||||||||||

The majority of clients who died during care were those enrolled in SIL, with a crude death rate of 90/1000 py for women and 62/1000 py for men. However, there was no significant difference in mortality rates between men and women across discharge programme (p = 0.309), age group (p = 0.672), or diagnosis group (p = 0.387).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated sex/gender differences in functional and psychosocial change, goal attainment, patterns of service use and death during post-acute care in a cohort of n = 1,011 adults with ABI during the period 1991–2020. These findings add to growing evidence of the effectiveness of post-acute care for individuals recovering from ABI (3–7), and improve our understanding of sex/gender differences in ABI recovery (22).

This study provided evidence of some sex/gender differences following ABI. At admission to services, women were significantly older than men, consistent with population statistics indicating that young men are at greatest risk of ABI (9). In addition, women presented to services with significantly poorer motor and overall functional independence than men, suggesting that women have greater disability due to ABI in the community. This was not the result of a longer wait between injury and support-seeking, as time from injury to admission did not differ between women and men, nor was it consistent with injury severity, as men had a significantly longer hospitalization prior to admission. There were no significant differences between men and women at admission in cognitive function, nor psychosocial function, in which men and women both demonstrated mild-to-moderate impairments.

Critically, there were no significant differences in magnitude of functional gains made by male and female clients throughout post-acute care. Between admission and discharge, both made statistically significant functional gains in Motor, Cognitive and Total FIM + FAM. Women also showed clinically significant improvements in Cognitive and Total FIM + FAM while men did not, suggesting that women may gain the most benefit from engaging in post-acute care. Neither male nor female clients made clinically significant improvements in Motor function.

With respect to psychosocial functioning, female clients significantly improved only in Total MPAI-4 and Participation, whereas men demonstrated significant improvements across all MPAI-4 domains. Men also demonstrated significantly larger gains in Participation relative to women. However, both men and women demonstrated small changes in every psychosocial domain, with neither men nor women meeting the cut-off for clinically significant change. Overall, psychosocial gains seen in this cohort are smaller than reported in similar programmes (7), suggesting that post-acute services can be improved to better target psychosocial function.

There were no sex/gender differences in either type of goal set or in their attainment in each ICF category. This is inconsistent with some previous research into TBI in which women demonstrated significantly higher goal attainment (39). However this previous study evaluated a home-based intervention, and most goals were attained, at odds with the post-acute setting and lower rates of attainment seen in the current cohort. These findings suggest that men and women can make meaningful gains in functional independence, and set attainable goals throughout the course of post-acute care, with women making sufficient gains to resolve functional differences seen at admission.

No significant differences in post-acute care LOS between women and men were identified in the current study. This is consistent with some prior research evaluating sex/gender differences in LOS throughout post-acute rehabilitation for TBI (27). However, sex/gender differences in LOS were identified for specific sub-groups in the current study. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women predicted significantly longer LOS than both Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander men and those not of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, with adjusted LOS 2 years longer than other groups. There is significant evidence recognizing the disproportionate burden of chronic disease in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people (40), which may explain additional LOS. In addition, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women had 59% greater probability of multiple episodes of care than Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander men. While there were a small numbers of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients in the cohort, this suggests a pattern of difficulty with service engagement and the need for additional discharge supports.

Living in the Metropolitan area predicted significantly shorter LOS in services for women than men, as did being partnered. Indeed, evidence in other chronic illnesses, such as cancer, has indicated that mothers may prioritize their children’s wellbeing above their own, even if this worsens their own health outcomes (41). Although this association has not been examined in mothers with ABI, these same sociological pressures may exist, preventing full engagement with services for women, and may result in shorter LOS. Finally, women in both SIL and CAPB had significantly shorter LOS than men in those same programmes. This may be the result of significant differences in age and type of ABI experienced by men and women, with men more likely to have a traumatic injury at a younger age (10), with younger men being the majority of individuals seeking rehabilitation services (6, 7). Therefore, when younger men are admitted to long-term programmes it may be for the remainder of their lives. This contrasts with research indicating that men are less likely that women to complete outpatient rehabilitation and more likely to discharge from hospital against medical advice (10).

There was no significant sex/gender difference in mortality during post-acute care. Current findings did not identify sex/gender differences in mortality during post-acute care by age, programme type or ABI diagnosis, although mortality was elevated in older age groups, and individuals in the SIL group did have the highest crude mortality rate, probably due to the specific profile of disease for those not seeking active rehabilitation and unable to return to independent living. Mortality risk in the cohort was significantly higher than in the general population, consistent with evidence of significant comorbidity burden (2, 42). However, the SMRs are similar to studies evaluating the mortality of individuals with ABI following discharge from acute care (43), despite differences in setting. While the absence of sex/gender differences in mortality are at odds with previous studies examining long-term sex differences in mortality following both stroke and TBI (18, 22), this may be related to care after discharge. Differences in mortality may not be present during post-acute care, where individuals have extensive medical and case management. However, following discharge individuals rely more heavily on informal supports, where sex/gender differences in risk factors play a role (18) and may explain the appearance of sex/gender differences in mortality post-discharge. It is important to note that this sample found a low level of mortality overall. Therefore, larger, population-based studies evaluating sex/gender differences in mortality for those accessing community services should be conducted, in order to further evaluate any sex/gender differences in this specific population.

Finally, women had significantly greater probability than men of requiring multiple episodes of care. Predictors included Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, partner status, metropolitan residence, socioeconomic disadvantage, diagnosis of TBI, admission to TRP, time since injury, no prior ABI, injury location and external cause of injury. This indicates systematic differences between women and men following discharge. This may be due to structural factors, such as the capacity of family units to support women following discharge, or the absence of appropriate community-based services. Consistent with this, women with bilateral or right hemispheric (RHS) injuries were more likely to require multiple episodes of care. As RHS injuries are associated with elements of visuospatial and executive dysfunction, such as attention, problem-solving, memory, social communication and anosognosia (lack of insight) (44), these specific limitations may influence women’s capacity to comprehensively plan for successful discharge from services, and care for themselves (and others) in the community. This may make them vulnerable to early discharge, a shorter length of stay, and the requirement of multiple episodes of care.

Socioeconomic disadvantage predicted multiple episodes of care for women, consistent with research indicating that women, particularly older women, are the fastest growing group of homeless individuals, with disability as a risk factor (45). Women with TBI and external cause of injury had greater probability of multiple episodes of care. This suggests that additional support may be required for these women once discharged into the community. With men making the greatest proportion of individuals with TBI (9), community services may prioritize the needs of men. Future research should identify post-discharge needs of women to allow development of programmes to support them in the community, avoiding readmission. Interestingly, women in the TRP programme were at increased risk of multiple episodes of care. As women also had shorter LOS in TRP, women may be discharging before robust discharge planning has occurred, increasing the risk of readmission. This indicates that future research should evaluate community services, to ensure women’s needs are being met.

Together, these finding indicate that post-acute neurorehabilitation and disability support is effective in supporting women to overcome the greater deficits seen at admission to post-acute services, with equivalent gains in functional and psychosocial independence, no differences in goal attainment, overall death rates or LOS. However, sex/gender differences in the number of episodes of care indicate difficulties in community integration for women following discharge, suggesting that more post-discharge support is needed.

Study limitations

These data were collected during routine care from a single ABI neurorehabilitation and disability support provider in Western Australia (WA); therefore the findings must be considered in this context. In addition, as this study is retrospective, it is important to recognize the limitations of such a method, primarily that clinical data of this type is not collected for research, leaving the potential for biased data collection, missing or incomplete data, and inadequate recording of confounding variables (46). While attempts have been made to control for this through the manual comparison of EMRs and linked data and comprehensive statistical controls, these findings must be considered carefully. Mortality rates included clients discharged by December 2020, before COVID-19 pandemic (SARS-CoV-2) community cases occurred in WA. Therefore, this may be an underrepresentation of current death rates, as this population has a high comorbidity burden, making them vulnerable to death due to COVID-19 (42). Indeed, while the mortality rates in this study were low, this is a relatively small sample for the examination of mortality rates, and, as such, it is possible that important differences were not identified. Finally, there are unequal numbers of women and men in the sample. This may indicate differences in the accessibility of post-acute care, potentially due to structural barriers impacting women’s engagement in targeted interventions, not purely due to differences in the numbers of men and women with severe ABI.

CONCLUSION

Despite sex/gender differences in functional independence at admission, women and men achieved significant functional and psychosocial improvement at discharge from post-acute rehabilitation and disability services for ABI. There were no sex/gender differences in goal setting or goal achievement, and women and men did not differ in their LOS or risk of death in post-acute services. However, women had a greater likelihood of requiring multiple episodes of care. This indicates that post-acute care is effective in managing the different requirements of women and men with ABI, but that additional community support may be required to enable women to re-integrate following discharge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the clients, families and staff at Brightwater Care Group who participated in this research.

This study was funded internally by Brightwater Care Group.

REFERENCES

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Disability in Australia: acquired brain injury. Bulletin no. 55. AUS 96. Canberra: AIHW; 2007.

- Masel BE, DeWitt DS. Traumatic brain injury: a disease process, not an event. J Neurotrauma 2010; 27: 1529–1540. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1358

- Groff AR, Malec J, Braunling-Mcmorrow D. Effectiveness of post-hospital intensive residential rehabilitation after acquired brain injury: outcomes of 256 program completers compared to participants in a residential supported living program. J Neurotrauma 2020; 37: 194–201. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5944

- Jackson D, Seaman K, Sharp K, Singer R, Wagland J, Turner-Stokes L. Staged residential post-acute rehabilitation for adults following acquired brain injury: a comparison of functional gains rated on the UK Functional Assessment Measure (UK FIM+FAM) and the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4). Brain Inj 2017; 31: 1405–1413. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1350998

- Troeung L, Mann G, Cullinan L, Wagland J, Martini A. Rehabilitation outcomes at discharge from staged community-based brain injury rehabilitation: a retrospective cohort study (ABI-RESTaRT), Western Australia, 2011–2020. Front Neurol 2022; 13. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.925225

- Borg DN, Nielsen M, Kennedy A, Drovandi C, Beadle E, Bohan JK, et al. The effect of access to a designated interdisciplinary post-acute rehabilitation service on participant outcomes after brain injury. Brain Inj 2020; 34: 1358–1366. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2020.1802660

- Curran C, Dorstyn D, Polychronis C, Denson L. Functional outcomes of community-based brain injury rehabilitation clients. Brain Inj 2015; 29: 25–32. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.948067

- Turner-Stokes L. Evidence for the effectiveness of multi-disciplinary rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: a synthesis of two systematic approaches. J Rehabil Med 2008; 40: 691–701. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0265

- Brain Injury Australia. About brain injury. 2016. [Accessed 20 January 2022]; Available from: https://www.braininjuryaustralia.org.au/

- Mollayeva T, Mollayeva S, Colantonio A. Traumatic brain injury: sex, gender and intersecting vulnerabilities. Nature Rev Neurol 2018; 14: 711–722. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0091-y

- Vaartjes I, Reitsma JB, Berger-van Sijl M, Bots ML. Gender differences in mortality after hospital admission for stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009; 28: 564–571. doi: 10.1159/000247600

- Phan HT, Gall SL, Blizzard CL, Lannin NA, Thrift AG, Anderson C, et al. Sex differences in care and long-term mortality after stroke: Australian Stroke Clinical Registry. J Womens Health 2019; 28: 712–720. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7171

- Stålnacke BM. Community integration, social support and life satisfaction in relation to symptoms 3 years after mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2007; 21: 933–942. doi: 10.1080/02699050701553189

- Poritz JMP, Vos L, Ngan E, Leon-Novelo L, Sherer M. Gender differences in employment and economic quality of life following traumatic brain injury. Rehabil Psychol 2019; 64: 65–71. doi: 10.1037/rep0000234

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Standard for sex and gender variables. 2016. [Accessed 11 March 2022]; Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/standard-sex-gender-variations-sex-characteristics-and-sexual-orientation-variables/2016.

- Niemeier JP, Marwitz JH, Lesher K, Walker WC, Bushnik T. Gender differences in executive functions following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2007; 17: 293–313. doi: 10.1080/09602010600814729

- Baguley IJ, Nott MT, Howle AA, Simpson GK, Browne S, King CA, et al. Late mortality after severe traumatic brain injury in New South Wales: a multicentre study. Med J Aust 2012; 196: 40–45. doi: 10.5694/mja11.10090

- Spitz G, Downing MG, McKenzie D, Ponsford J. Mortality following traumatic brain injury inpatient rehabilitation. J Neurotrauma 2015; 32: 1272–1280.

- Ponsford JL, Myles PS, Cooper DJ, Mcdermott FT, Murray LJ, Laidlaw J, et al. Gender differences in outcome in patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury. Injury 2008; 39: 67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.08.028

- Colantonio A, Harris JE, Ratcliff G, Chase S, Ellis K. Gender differences in self reported long term outcomes following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. BMC Neurol 2010; 10: 102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-102

- Fabricius AM, D’Souza A, Amodio V, Colantonio A, Mollayeva T. women’s gendered experiences of traumatic brain injury. Qual Health Res 2020; 30: 1033–1044. doi: 10.1177/1049732319900163

- Carcel C, Woodward M, Wang X, Bushnell C, Sandset EC. Sex matters in stroke: a review of recent evidence on the differences between women and men. Front Neuroendocrinol 2020; 59. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2020.100870

- Gall SL, Tran PL, Martin K, Blizzard L, Srikanth V. Sex differences in long-term outcomes after stroke. Stroke 2012; 43: 1982–1987. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.632547

- Malec JF, Basford JS. Postacute brain injury rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77: 198–207. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(96)90168-9

- Evans CC, Sherer M, Nakase-Richardson R, Mani T, Irby JW. Evaluation of an interdisciplinary team intervention to improve therapeutic alliance in post–acute brain injury rehabilitation. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2008; 23: 329–338. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000336845.06704.bc

- Powell J, Heslin J, Greenwood R. Community based rehabilitation after severe traumatic brain injury: a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72: 193–202.

- Chan V, Mollayeva T, Ottenbacher KJ, Colantonio A. Sex-specific predictors of inpatient rehabilitation outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016; 97: 772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.01.011

- Mann G, Troeung L, Wagland J, Martini A. Cohort profile: The Acquired Brain Injury Community REhabilitation and Support Services OuTcomes CohoRT (ABI-RESTaRT), Western Australia, 1991-2020. BMJ Open 2021; 11: 1–15. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052728

- Department of Health Government of Western Australia. Data Linkage Western Australia. 2020. [Accessed 24 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.datalinkage-wa.org.au/

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. The Australian statistical geography standard (ASGS) remoteness structure. 2018. [accessed 2023 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/remoteness+structure

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-economic indexes for areas. 2018. [accessed 2023 Jan10]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifa

- Turner-Stokes L, Nyein K, Turner-Stokes T, Gatehouse C. The UK FIM+FAM: development and evaluation. Clin Rehabil 1999; 13: 277–287. doi: 10.1191/026921599676896799

- Turner-Stokes L, Siegert RJ. A comprehensive psychometric evaluation of the UK FIM + FAM. Disabil Rehabil 2013; 35: 1885–1895. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.766271

- Malec J, Lezak MD. The Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4). 2003.

- Malec JF, Kean J, Monahan PO. The minimal clinically important difference for the Mayo-Portland adaptability inventory. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2017; 32: E47–54. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000268

- Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil 2009; 23: 362–370. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101742

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 2017. [Accessed 18 July 2022]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/

- Hurn J, Kneebone I, Cropley M. Goal setting as an outcome measure: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2006; 20: 756–772. doi: 10.1177/0269215506070793

- Borgen IMH, Hauger SL, Forslund MV, Kleffelgard I, Brunborg C, Andelic N, et al. Goal attainment in an individually tailored and home-based intervention in the chronic phase after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Med 2022; 11. doi: 10.3390/jcm11040958

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. Australian Burden of Disease Study series no. 26. Cat. no. BOD 32. Canberra: AIHW; 2022.

- Mackenzie CR. ‘It is hard for mums to put themselves first’: How mothers diagnosed with breast cancer manage the sociological boundaries between paid work, family and caring for the self. Soc Sci Med 2014; 117: 96–106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.043

- Troeung L, Mann G, Wagland J, Martini A. Effects of comorbidity on post-acute outcomes in acquired brain injury: ABI-RESTaRT 1991–2020. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2022; 66: 101669. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2022.101669

- Colantonio A, Escobar MD, Chipman M, McLellan B, Austin PC, Mirabella G, Ratcliff G. Predictors of postacute mortality following traumatic brain injury in a seriously injured population. J Trauma 2008; 64: 876–882. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31804d493e

- Blake ML, Duffy JR, Myers PS, Tompkins CA. Prevalence and patterns of right hemisphere cognitive/communicative deficits: retrospective data from an inpatient rehabilitation unit. Aphasiology 2002; 16: 537–547. doi: 10.1080/02687030244000194

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Older women’s risk of homelessness: background paper. Australian Human Rights Commission 2019. [accessed 2022 Sept 2] Available from: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/age-discrimination/publications/older-womens-risk-homelessness-background-paper-2019

- Talari K, Goyal M. Retrospective studies – utility and caveats. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2020; 50: 398–402. doi: 10.4997/jrcpe.2020.409