Objective: To explore how persons who have returned to work perceive their work situation and work ability one year after stroke.

Design: Cross-sectional design.

Subjects: A total of 88 persons of working age (mean age 52 (standard deviation; SD 8) years, 36% women), with mild to moderate disabilities following stroke, who had returned to work within one year after stroke participated in the study.

Methods: A survey including a questionnaire regarding psychological and social factors at work (QPS Nordic) and 4 questions from the Work Ability Index (WAI) was posted to the participants.

Results: According to the QPS Nordic survey, 69–94% of respondents perceived their work duties as well defined, and were content with their work performance. Most participants had good social support at work and at home. Between 51% and 64% of respondents reported that they seldom felt stressed at work, seldom had to work overtime, or that work demands seldom interfered with family life. According to the WAI ≥75% of respondents perceived their work ability as sufficient, and they were rather sure that they would still be working 2 years ahead.

Conclusion: Persons who have returned to work within one year after stroke appear to be content with their work situation and work ability. Appreciation at work, well-defined and meaningful work duties and support seem to be important for a sustainable work situation.

Key words: stroke; impairment; vocational rehabilitation; adjustment; work situation.

Accepted Nov 12, 2021; Epub ahead of print Nov 26, 2021

J Rehabil Med 2022; 54: jrm00254

doi: 10.2340/jrm.v53.918

Correspondence address: Ingrid Lindgren, Department of Health Sciences, Lund University, SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden. E-mail: ingrid. lindgren@med.lu.se

LAY ABSTRACT

To be able to return to work after stroke is important for health and well-being. In this study, 88 persons who were working at one year after stroke responded to a survey including questionnaires regarding psychological and social factors at work, and work ability. A majority of respondents perceived that their skills and knowledge were useful, that their work duties were well defined and that they were content with their work performance. Most of them had good social support in the workplace and from family and friends. A majority (≥75%) considered their work ability to be rather good or very good, and were reasonably sure that they would be working for a further 2 years. These findings indicate that persons who are working at one year after stroke seem to be content with their work situation and work ability. Individual adjustments, meaningful work duties and support are important for a successful and sustainable work situation.

INTRODUCTION

In Sweden, approximately 25,000 persons have a stroke every year, of whom approximately 15% are <65 years (a common retirement age in Sweden) (1, 2). A variety of impairments may occur after stroke, such as muscle weakness, aphasia, fatigue, concentration difficulties and memory problems, which could impede work ability in both the short- and long-term (3–7). To have the opportunity to return to work (RTW) after stroke is important for health and well-being (8), and will also contribute to relieving the economic burden on the social welfare system (9). The proportion of persons who RTW after stroke differs between studies, from 19% to 73% (10–12). Differences in social insurance systems between countries, as well as the definition of RTW might impact the rate of RTW (13). A Swedish study reported an almost 70% RTW within one year after stroke, and up to 80% within 2 years (14). However, many persons with mild or moderate disabilities following stroke have reduced their working time one year after their injury (15). Thus, to facilitate a sustainable work situation after stroke is important (6).

Even though current medical treatments, such as thrombolysis and thrombectomy, can reduce stroke impairments (16), persons may have remaining hidden disabilities that impede their work ability. In addition, high rates of sick leave, related to stroke and comorbidities, have been reported several years after having RTW (17). This indicates that adjustments and support at work are important to optimize work ability after stroke (7, 18).

Work ability can be regarded as a balance between a person’s resources and the demands of work. ‘”Work” is linked to health and functional abilities, values, attitudes, education, work skills and health practices, and “ability”’ to the actual content, demands and organization of work, as well as the total working environment (19). In our previous study (20), we found that adjustments at the workplace, social support, attitude and motivation to work influenced RTW. Several environmental and organizational factors linked to occupational health in general have been reported. Lindström (21) emphasized that it is important to consider and adjust quantitative and qualitative workload, job control, clear work roles and job support for each individual. These factors may also need consideration in the RTW process after stroke.

Thus, the ability to RTW and to remain working after stroke is a complex process that involves both aspects related to impairments following stroke, the individual’s attitudes towards work, and the workplace situation. There is, however, a need for increased knowledge of how persons who have had a stroke experience their work situation and work ability (6, 7, 22). A deeper knowledge could improve the long term vocational rehabilitation process after stroke. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to explore how persons who have RTW perceive their work situation and work ability one year after stroke.

METHODS

Study design

This study has a cross-sectional design, and is based on a postal survey sent to persons who had had a stroke 10–14 months earlier and had worked prior to stroke onset. The survey comprised background information, questions related to RTW and rating scales about work situation, work ability, self-efficacy, fatigue and life satisfaction (see Data collection). In this study, only data regarding perceived work situation and work ability are reported.

Recruitment of participants

The participants were recruited from Skåne University Hospital (Sweden) between January 2016 and September 2018, with the following inclusion criteria: admitted to hospital for acute care due to stroke; aged 18–64 years at stroke onset; referred to the hospital’s stroke rehabilitation outpatient clinic within 180 days after stroke onset; and worked at least 10 h per week prior to stroke. Persons not fluent in Swedish or who had severe cognitive and/or language impairments making them unable to respond to the questionnaire were excluded.

A total of 344 potential participants were identified through the hospital administrative system. Further information was obtained through medical records. A total of 178 persons met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 110 persons responded that they were interested in participating in the study. Among these, 88 persons had RTW, and were still working and thus were included in the current study. A flow chart of the recruitment process is shown in Fig. 1.

Data collection

Information about the study, an informed consent form, socio-demographics questions, questionnaires regarding stroke, overall health and work, and a pre-stamped return envelope were sent by post to the participants. After 2 weeks a reminder was sent to non-responders.

Sociodemographics, perceived health, and work-related questions. Sociodemographic data included age, sex, stroke type, country of birth, living situation and education. The Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) (23), item 9, was used to assess perceived recovery, rated on a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no recovery) to 100 (full recovery) (23). The Life Satisfaction questionnaire (LiSat-11), item 1 “Life as a whole” was used to assess global life satisfaction, on a 1–6 rating scale (higher score = better) (24). Fatigue was assessed according to the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS; possible total score 1–7, higher = worse) (25), where a cut-off ≥ 4 indicates fatigue (26). Work-related questions included RTW rehabilitation, time from injury to RTW, working time (%) before and after stroke, form of employment (private/public), work organization, monthly income, period worked at the present workplace, work schedule and type of work.

Psychological and social factors at work. The General Nordic Questionnaire for Psychological and Social Factors at Work (QPS Nordic) was used to assess psychological and social factors at work (27). The QPS Nordic is a reliable and valid questionnaire that measures work level, social and organizational level and individual level. It comprises 14 subscales with 2–5 questions in each subscale. In the current study, the following subscales were used: Job demands, Positive expectations, Role expectations, Control at work, Work pace control, Mastery of work, Social support from manager, Social support from co-workers, Social support from friends and family, Internal work motives and External work motives. The single-item questions concerning interaction between work and private life were also included. Each question has 5 response categories, ranging from 1 to 5, but for brevity the response options were merged into 3 groups; 1–2, 3, and 4–5 according to the manual of the QPS Nordic (27). Subscale scores were presented as mean scores (ranging from 1 to 5 for each subscale). In all subscales except “Job demands” and the questions in “Interaction between work and private life” a higher score is better. Mean scores for each subscale from a reference sample (n = 2010) are available in the QPS Nordic manual (27).

Work ability. Perceived work ability was assessed according to the questions in item 1 (1 question), item 2 (2 questions) and item 6 (1 question) in the Work Ability Index (WAI) (28). The WAI is a multidimensional diagnostic tool for assessing work ability and comprises 7 items in total (28, 29). The question in item 1, also called the Work Ability Score (WAS), can be used as a proxy for the WAI (30, 31).

Data analysis

Descriptive data of the participants’ demographics, perceived health, work situation and work ability are presented as mean (standard deviation; SD), median (range) and n (%). Data for psychological and social factors at work according to QPS Nordic are presented as percent and mean (SD). For differences between the study population and the reference population, independent t-test was used. After Bonferroni correction, p-values < 0.005 were considered significant.

Ethics

All individuals gave written informed consent to participate. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Lund, Sweden (Dnr 2016/1064).

RESULTS

Sociodemographics, perceived health status and work-related questions

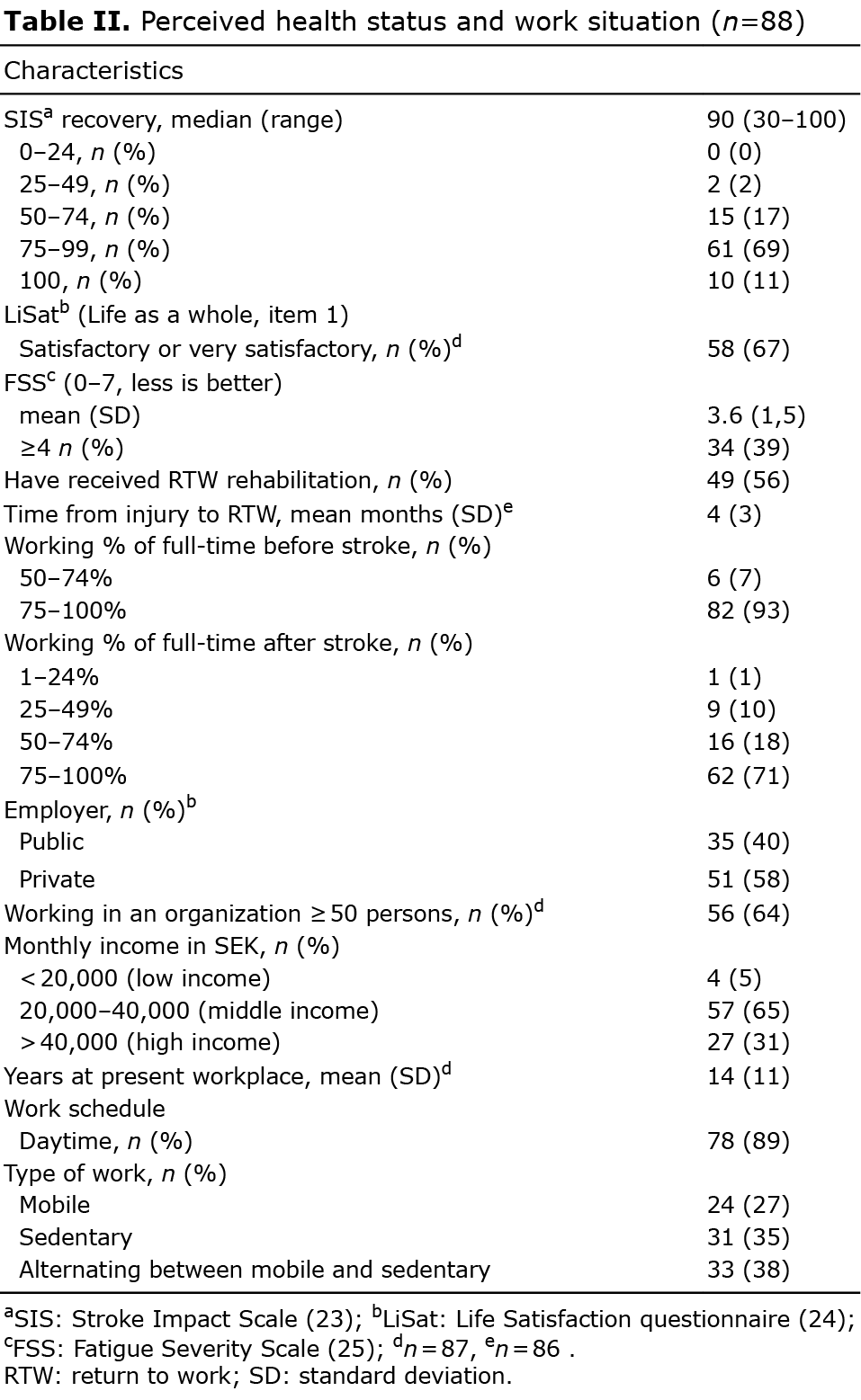

The mean age of the 88 persons who had RTW and were still working after one year was 52 years (SD 8), and 36% were women. A majority of the participants had had an ischaemic stroke. Most of them were born in Sweden and had high school or university education (Table I). They had mild to moderate disability, corresponding to levels 1–3 in the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) (32). The median perceived recovery from stroke one year after the injury was 90% according to the SIS. All participants could habitually walk without using walking aids. Life as a whole was reported as satisfactory or very satisfactory by a majority, but 39% of the participants experienced fatigue (i.e. ≥ 4 on the FSS).

Time from injury to start of work was, on average, 4 months. Before stroke, 93% of the participants worked 75–100% of full-time hours, and after stroke 71% of the participants did so. A majority of participants worked in the private sector, worked in large organizations, had worked for a long time in the same organization, had middle or high incomes and worked in the daytime. The type of work (mobile or sedentary) varied among participants (Table II).

Psychological and social factors at work

According to the QPS Nordic (Table III), a majority of the participants considered that they had a good or very good work situation. The highest scores were reported in the subscales Positive expectations, Role expectations, Mastery of work and Social support from manager, co-workers and friends. Between 69% and 94% of participants perceived that their skills and knowledge were useful in their work, and that their work was challenging and meaningful. In addition, most of the participants (70–90%) perceived that their goals were planned and work duties defined. Between 74% and 90% of participants were content with the work they produced, and perceived that they had a good relationship with their co-workers. Most participants (59–83%) had support from their manager, co-workers, friends and family and could get help when needed. Only a minority (7–28%) reported that they had to work overtime, had too much to do, or had an irregular workload. Approximately half or three-quarters of the participants stated that they could rather often, very often or always choose alternative methods at work if necessary and could influence decision-making. Many could also influence the pace of their work, decide when to take a break and for how long, and had flexitime work.

Regarding work motives, 71% reported that it was important to get a sense of accomplishing something worthwhile. Similarly, 65–69% reported that it was important to have work security and a regular income as well as a safe and healthy physical work environment. Fifty-one percent scored “not at all” or “very little” work-related stress. In the single questions relating to work and private life, 59–78% considered that work seldom interfered with their private life (Table III).

In Table IV, total sum scores and p-values of the QPS Nordic subscales Job demands, Positive expectations, Role expectations, Control at work, Work pace control, Mastery of work, Social support and Work motives are presented, together with figures from the reference sample. The participants reported significantly higher/better scores than the reference sample in Job demands, Positive expectations, Control at work, Work pace control, Mastery of work, Social support from manager and Social support from co-workers (p < 0.001–< 0.002). In contrast, our sample reported significantly lower/worse scores than the reference sample in questions related to intrinsic work motives (p < 0.001).

Work ability

The 4 questions in the WAI are shown in Table V. In the WAS current work ability compared with lifetime work ability was scored good or excellent by 59% of participants. In the questions regarding work ability in relation to physical and mental work demands, a majority scored their ability as rather good or very good (84% and 75%, respectively). According to the question about Future Work Ability (FWA), 79% scored that they were rather sure that they would still be working 2 years ahead.

DISCUSSION

This postal survey aimed to explore how people who had RTW and still worked one year after stroke perceived their work situation and work ability. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has used the QPS Nordic and WAI in persons after stroke. A vast majority of the participants considered that their skills and knowledge were useful in their work and that their work duties were well defined. They were content with the work they performed and had support from their managers, colleagues and families. In a majority of the QPS subscales, the scores from the study population were significantly better than the reference sample. A majority (≥ 75%) scored their work ability in relation to physical and mental work demands as rather good or very good. Approximately 80% scored that they were relatively certain that they would still be working 2 years ahead. The results indicate that persons working in well-functioning organizations, who have support from the workplace and their family also seem to have good opportunities to RTW and stay at work in the longer term.

Aspects that were found to be important for a good and sustainable work situation were: meaningful and challenging work duties, that work roles were clearly defined, that the person was content with their work performance, was able to have control over the pace of their work, and had a regular income and a safe and healthy physical work environment. These aspects are also considered important for a good work organization from a general perspective (21). Concerning persons who had RTW after stroke, returning to a former employment with well-known work tasks has been emphasized as important (33). In addition, for a sustainable work situation, independence and skill confidence have been reported to be of positive significance (5).

Although most of the participants in the current study considered themselves to be fairly or very well recovered from stroke, approximately 40% reported fatigue according to the FSS. However, a vast majority perceived that their physical and mental capacity corresponded well to their work ability, and they considered that they would still be working 2 years ahead. A qualitative study found that many persons feel restricted in their work situation many years after stroke and struggle with impairments, even though they are motivated (6). Hidden disabilities, such as fatigue and concentration problems, have been reported as a hindrance in the work situation (7, 18). However, other studies have reported that flexibility in the work schedule (5, 20), reduced working hours (5), and support from family, manager and colleagues (20), might be helpful in dealing with such impairments. This indicates that appropriate adjustments in the workplace and support are of importance for a sustainable work situation. Moreover, approximately 20% of our participants had reduced their working hours, which is in agreement with a previous study (15). To determine the right level of work capacity could be a long process (34, 35), and after stroke persons might need support in order to set realistic work goals. A workplace intervention programme tailored to the person’s ability and the workplace challenges has been reported to facilitate RTW and to establish an optimal work situation (36). Another important aspect is to reduce stress. Approximately half of the participants in the current study reported that they had not been stressed recently in relation to their work, which is a very positive result. In studies targeting stroke and RTW, stress is mentioned as a common hindering factor (5, 33).

Furthermore, a majority of the participants in the current study considered that they had social support at the workplace and from friends and family. The meaning of support has been emphasized in several studies. Understanding from the employer or supervisor has a central role (6, 18), and support from colleagues (4, 6, 7, 20) can help the person to feel comfortable with their work situation. A supportive workplace environment facilitates communication and enables employees to request help when needed (18, 20). However, to enable the management of work duties, psychosocial and practical family support may be needed (20).

Overall, in most of the QPS subscales, except work motives, the participants reported significantly better scores on QPS Nordic than the reference sample. Possible reasons for these results could be that just over half (56%) of the participants reported that they had received RTW rehabilitation. In addition, most of the participants perceived a good stroke recovery, lived with a spouse, reported high life satisfaction, had high education, had worked for a long time in the same organization, and worked in a large organization. These factors have been reported to facilitate RTW (37, 38). However, having a stroke might alter the persons’ views of important values in their life (18). Some persons might re-evaluate their attitude to work and strive for a better balance between work and family life (20, 33) or consider early retirement (20). For many persons, the stroke affects work a great deal (39). To help persons to achieve a sustainable work situation is therefore of importance, not only for the stroke-affected person, but also to reduce societal costs (9). With optimal adjustments, persons might be able to continue working longer (40). For professionals who strive to help persons to achieve a sustainable work situation after sick leave, it is important to consider how the person evaluates his or her work ability. To pay attention to the WAI questions targeting perceived work ability and future work ability might contribute to a broader perspective.

Methodological considerations

A strength of the current study was the large population with 88 participants and that well-known and established instruments and questionnaires were used. The QPS Nordic measures both the work level, social and organizational level, as well as the individual level, and provides broad knowledge covering the entire work situation. It can be used both to evaluate local workplace reorganization and in research (27). The work ability concept resulting in the WAI was introduced several decades ago (28). The WAI is suitable to map work ability at the group level in research, but individual questions might also be useful at a person level and thus useful in clinical settings. A limitation of the current study was that we had a selected well-functioning group; therefore the results cannot be generalized to the whole stroke population of working age. The survey was sent out to all persons who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, but those who did not send back the survey had RTW to a lesser extent. Other limitations are that cognitive function and depression were not assessed. Future studies should focus on how to deepen knowledge on which areas are of importance for achieving and maintaining a sustainable work situation and to include a broader group of persons affected by stroke.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that persons who work one year after stroke seem to be contented with their work situation and work ability. Appreciation at work, well-defined and meaningful work duties and support appear to be important for a sustainable work situation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all participants who answered the survey. We also thank RPT, PhD Michael Miller for language editing. Financial support was received from the Färs and Frosta Foundation, the Promobilia foundation, the Swedish Stroke Association, the Norrbacka-Eugenia foundation and Skåne University Hospital foundations and donations.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Riksstroke the Swedish stroke register. Årsrapport stroke TIA 2019. Umeå: Riksstroke the Swedish stroke register; 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 1]. Available from: http://www.riksstroke.org/sve/forskning-statistik-och-verksamhetsutveckling/rapporter/arsrapporter/.

- Socialstyrelsen (National Report on Health and Welfare S. Statistik om stroke (Statistical database stroke) 2019. [cited Sept 23, 2021] Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/statistik/statistikamnen/stroke/.

- Jokinen H, Melkas S, Ylikoski R, Pohjasvaara T, Kaste M, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Post-stroke cognitive impairment is common even after successful clinical recovery. Eur J Neurol 2015; 22: 1288–1294.

- Lindström B, Röding J, Sundelin G. Positive attitudes and preserved high level of motor performance are important factors for return to work in younger persons after stroke: a national survey. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 714–718.

- Hartke RJ, Trierweiler R. Survey of survivors’ perspective on return to work after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2015; 22: 326–334.

- Palstam A, Törnbom M, Sunnerhagen KS. Experiences of returning to work and maintaining work 7 to 8 years after a stroke: a qualitative interview study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e021182.

- Balasooriya-Smeekens C, Bateman A, Mant J, De Simoni A. Barriers and facilitators to staying in work after stroke: insight from an online forum. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e009974.

- Wang YC, Kapellusch J, Garg A. Important factors influencing the return to work after stroke. Work 2014; 47: 553–559.

- Garland A, Jeon SH, Stepner M, Rotermann M, Fransoo R, Wunsch H, et al. Effects of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health events on work and earnings: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ 2019; 191: E3–E10.

- Chang WH, Sohn MK, Lee J, Kim DY, Lee SG, Shin YI, et al. Return to work after stroke: The KOSCO Study. J Rehabil Med 2016; 48: 273–279.

- Aarnio K, Rodriguez-Pardo J, Siegerink B, Hardt J, Broman J, Tulkki L, et al. Return to work after ischemic stroke in young adults: a registry-based follow-up study. Neurology. 2018; 91: e1909–e1917.

- Treger I, Shames J, Giaquinto S, Ring H. Return to work in stroke patients. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1397–1403.

- Edwards JD, Kapoor A, Linkewich E, Swartz RH. Return to work after young stroke: a systematic review. Int J Stroke 2018; 13: 243–256.

- Westerlind E, Persson HC, Sunnerhagen KS. Return to work after a stroke in working age persons; a six-year follow up. PLoS One. 2017; 12: e0169759.

- van der Kemp J, Kruithof WJ, Nijboer TCW, van Bennekom CAM, van Heugten C, Visser-Meily JMA. Return to work after mild-to-moderate stroke: work satisfaction and predictive factors. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2019; 29: 638–653.

- Campbell BCV, Khatri P. Stroke. Lancet 2020; 396: 129–142.

- Lallukka T, Ervasti J, Lundström E, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Friberg E, Virtanen M, et al. Trends in diagnosis-specific work disability before and after stroke: a longitudinal population-based study in Sweden. J Am Heart Assoc 2018; 7: e006991.

- Alaszewski A, Alaszewski H, Potter J, Penhale B. Working after a stroke: survivors’ experiences and perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of the return to paid employment. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1858–1869.

- Fadyl JK, McPherson KM, Schluter PJ, Turner-Stokes L. Factors contributing to work-ability for injured workers: literature review and comparison with available measures. Disabil Rehabil 2010; 32: 1173–1183.

- Lindgren I, Brogårdh C, Pessah-Rasmussen H, Jonasson SB, Gard G. Work conditions, support, and changing personal priorities are perceived important for return to work and for stay at work after stroke – a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2020: Oct 26 [Online ahead of print]

- Lindström K. Psychosocial criteria for good work organization. Scand J Work Environ Health 1994; 20: 123–133.

- Han J, Lee HI, Shin YI, Son JH, Kim SY, Kim DY, et al. Factors influencing return to work after stroke: the Korean Stroke Cohort for Functioning and Rehabilitation (KOSCO) study. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e028673.

- Duncan PW, Wallace D, Lai SM, Johnson D, Embretson S, Laster LJ. The stroke impact scale version 2.0. Evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke 1999; 30: 2131–2140.

- Fugl-Meyer AR, Melin R, Fugl-Meyer KS. Life satisfaction in 18- to 64-year-old Swedes: in relation to gender, age, partner and immigrant status. J Rehabil Med 2002; 34: 239–246.

- Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989; 46: 1121–1123.

- Cumming TB, Packer M, Kramer SF, English C. The prevalence of fatigue after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Stroke 2016; 11: 968–977.

- Lindström K, Dallner M, Elo A-L, Gamberale F, Knardahl S, Skogstad A, Örhede E (eds.). Copenhagen; 1997. Contract No.: 1997: 15.

- Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Jahkola A, Katajarinne L and Tulkki A. Work Ability Index. 2nd edn. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; 1998.

- Ilmarinen J. Work ability – a comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scand J Work Environ Health 2009; 35: 1–5.

- Lundin A, Leijon O, Vaez M, Hallgren M, Torgen M. Predictive validity of the Work Ability Index and its individual items in the general population. Scand J Public Health 2017; 45: 350–356.

- Ahlström L, Grimby-Ekman A, Hagberg M, Dellve L. The Work Ability Index and single-item question: associations with sick leave, symptoms, and health – a prospective study of women on long-term sick leave. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010; 36: 404–412.

- van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988; 19: 604–607.

- Hartke RJ, Trierweiler R, Bode R. Critical factors related to return to work after stroke: a qualitative study. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011; 18: 341–351.

- Culler KH, Wang YC, Byers K, Trierweiler R. Barriers and facilitators of return to work for individuals with strokes: perspectives of the stroke survivor, vocational specialist, and employer. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011; 18: 325–340.

- Hellman T, Bergström A, Eriksson G, Hansen Falkdal A, Johansson U. Return to work after stroke: Important aspects shared and contrasted by five stakeholder groups. Work 2016; 55: 901–911.

- Ntsiea MV, Van Aswegen H, Lord S, Olorunju SS. The effect of a workplace intervention programme on return to work after stroke: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2015; 29: 663–673.

- Larsen LP, Biering K, Johnsen SP, Andersen G, Hjollund NH. Self-rated health and return to work after first-time stroke. J Rehabil Med 2016; 48: 339–345.

- Palstam A, Westerlind E, Persson HC, Sunnerhagen KS. Work-related predictors for return to work after stroke. Acta Neurol Scand 2019; 139: 382–388.

- Radford K, Grant MI, Sinclair EJ, Kettlewell J, Watkin C. Describing return to work after stroke: a feasibility trial of 12-month outcomes. J Rehabil Med 2020; 52: jrm00048.

- Reeuwijk KG, de Wind A, Westerman MJ, Ybema JF, van der Beek AJ, Geuskens GA. “All those things together made me retire”: qualitative study on early retirement among Dutch employees. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 516.